Brine

| Part of a series on |

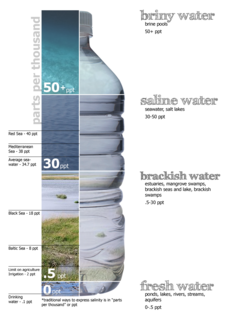

| Water salinity |

|---|

|

Salinity levels |

Fresh water (< 0.05%) Brackish water (0.05–3%) Saline water (3–5%) Brine (> 5% up to 26%-28% max) |

Bodies of water |

|

Brine is a high-concentration solution of salt (usually sodium chloride) in water. In different contexts, brine may refer to salt solutions ranging from about 3.5% (a typical concentration of seawater, on the lower end of solutions used for brining foods) up to about 26% (a typical saturated solution, depending on temperature). Lower levels of concentration are called by different names: fresh water, brackish water, and saline water.

Brine naturally occurs on Earth's surface (salt lakes), crust, and within brine pools on ocean bottom. High-concentration brine lakes typically emerge due to evaporation of ground saline water on high ambient temperatures. Brine is used for food processing and cooking (pickling and brining), for de-icing of roads and other structures, and in a number of technological processes. It is also a by-product of many industrial processes, such as desalination, and may pose an environmental risk due to its corrosive and toxic effects, so it requires wastewater treatment for proper disposal.

Contents

1 In nature

2 Uses

2.1 Culinary

2.2 Chlorine production

2.3 Refrigerating fluid

2.4 Water softening and purification

2.5 De-icing

3 Wastewater

4 See also

5 References

In nature

A NASA technician measures the concentration level of brine using a hydrometer at a salt evaporation pond in San Francisco.

Saline water with relatively high concentration of salt (usually sodium chloride) occurs naturally on Earth's surface (salt lakes), crust, and within brine pools on ocean bottom.

Numerous processes exist which can produce brines in nature. Modification of seawater via evaporation results in the concentration of salts in the residual fluid, a characteristic geologic deposit called an evaporite is formed as different dissolved ions reach the saturation states of minerals, typically gypsum and halite. A similar process occurs at high latitudes as seawater freezes resulting in a fluid termed a cryogenic brine. At the time of formation, these cryogenic brines are by definition cooler than the freezing temperature of seawater and can produce a feature called a brinicle where cool brines descend, freezing the surrounding seawater.

The brine cropping out at the surface as saltwater springs are known as "licks" or "salines".[1] The contents of dissolved solids in groundwater vary highly from one location to another on Earth, both in terms of specific constituents (e.g. halite, anhydrite, carbonates, gypsum, fluoride-salts, organic halides, and sulfate-salts) and regarding the concentration level. Using one of several classification of groundwater based on total dissolved solids (TDS), brine is water containing more than 100,000 mg/L TDS.[2] Brine is commonly produced during well completion operations, particularly after the hydraulic fracturing of a well.

Uses

Culinary

Brine is a common agent in food processing and cooking. Brining is used to preserve or season the food. Brining can be applied to vegetables, cheeses and fruit in a process known as pickling. Meat and fish are typically steeped in brine for shorter periods of time, as a form of marination, enhancing its tenderness and flavor, or to enhance shelf period.

Chlorine production

Elemental chlorine can be produced by electrolysis of brine (NaCl solution). This process also produces sodium hydroxide (NaOH) and Hydrogen gas (H2). The reaction equations are as follows:

- Cathode: 2H++2e−⟶H2↑{displaystyle {ce {2 H+ + 2 e- -> H2 (^)}}}

- Anode: 2Cl−⟶Cl2↑+2e−{displaystyle {ce {2 Cl- -> Cl2 (^) + 2 e-}}}

- Overall process: 2NaCl+2H2O⟶Cl2+H2+2NaOH{displaystyle {ce {2 NaCl + 2 H2O -> Cl2 + H2 + 2 NaOH}}}

Refrigerating fluid

Brine is used as a secondary fluid in large refrigeration installations for the transport of thermal energy from place to place. Most commonly used brines are based on inexpensive calcium chloride and sodium chloride.[3] It is used because the addition of salt to water lowers the freezing temperature of the solution and the heat transport efficiency can be greatly enhanced for the comparatively low cost of the material. The lowest freezing point obtainable for NaCl brine is −21.1 °C (−6.0 °F) at the concentration of 23.3% NaCl by weight.[3] This is called the eutectic point.

Sodium chloride brine spray is used on some fishing vessels to freeze fish.[4] The brine temperature is generally −5 °F (−21 °C). Air blast freezing temperatures are −31 °F (−35 °C) or lower. Given the higher temperature of brine, the system efficiency over air blast freezing can be higher. High-value fish usually are frozen at much lower temperatures, below the practical temperature limit for brine.

Because of the corrosive properties of salt-based brines, glycols such as polyethylene glycol have become more common for this purpose.[5]

Water softening and purification

Brine is an auxiliary agent in water softening and water purification systems involving ion exchange technology. The most common example are household dishwashers, utilizing natrium chloride in form of dishwasher salt. Brine is not involved in the purification process itself, but used for regeneration of ion-exchange resin on cyclical basis. The water being treated flows through the resin container until the resin is considered exhausted and water is purified to a desired level. Resin is then regenerated by sequentially backwashing the resin bed to remove accumulated solids, flushing removed ions from the resin with a concentrated solution of replacement ions, and rinsing the flushing solution from the resin.[6] After treatment, ion-exchange resin beads saturated with calcium and magnesium ions from the treated water, are regenerated by soaking in brine containing 6–12% NaCl. The sodium ions from brine replace the calcium and magnesium ions on the beads.[7][8]

De-icing

In lower temperatures, a brine solution can be used to de-ice or reduce freezing temperatures on roads.[9]

Wastewater

Brine is a byproduct of many industrial processes, such as desalination for human consumption and irrigation, power plant cooling towers, produced water from oil and natural gas extraction, acid mine or acid rock drainage, reverse osmosis reject, chlor-alkali wastewater treatment, pulp and paper mill effluent, and waste streams from food and beverage processing. Along with diluted salts, it can contain residues of pretreatment and cleaning chemicals, their reaction byproducts and heavy metals due to corrosion.

Wastewater brine can pose a significant environmental hazard, both due to corrosive and sediment-forming effects of salts and toxicity of other chemicals diluted in it. It must be properly disposed, which may require permits and compliance with environmental regulations.[10]

The simplest way to dispose of unpolluted brine from desalination plants and cooling towers is to return it back to the ocean. To limit the environmental impact, it can be diluted with another stream of water, such as the outfall of a wastewater treatment or power plant. Since brine is heavier than seawater and would accumulate on the ocean bottom, it requires methods to ensure proper diffusion, such as installing underwater diffusers in the sewerage.[11] Other methods include drying in evaporation ponds, injecting to deep wells, and storing and reusing the brine for irrigation, de-icing or dust control purposes.[10]

Technologies for treatment of polluted brine include: membrane filtration processes, such as reverse osmosis; ion exchange processes such as electrodialysis or weak acid cation exchange; or evaporation processes, such as brine concentrators and crystallizers employing mechanical vapour recompression and steam.

See also

- Brine mining

Brinicle – A downward growing hollow tube of ice enclosing a plume of descending brine that is formed beneath developing sea ice

References

^ "The Scioto Saline-Ohio's Early Salt Industry" (PDF). dnr.state.oh.us. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-10-07..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ "Global Overview of Saline Groundwater Occurrence and Genesis". igrac.net.

^ ab "Secondary Refrigerant Systems". Cool-Info.com. Retrieved 17 July 2017.

^ Kolbe, Edward; Kramer, Donald (2007). "Planning forSeafood Freezing" (PDF). Alaska Sea Grant College Program Oregon State University. ISBN 1566121191. Retrieved 17 July 2017.

^ "Calcium Chloride versus Glycol". accent-refrigeration.com. Retrieved 17 July 2017.

^ Kemmer, Frank N., ed. (1979). The NALCO Water Handbook. McGraw-Hill. pp. 12–7, 12–25.

^ "Hard and soft water". GCSE Bitesize. BBC.

^ Arup K. SenGupta (19 April 2016). Ion Exchange and Solvent Extraction: A Series of Advances. CRC Press. pp. 125–. ISBN 978-1-4398-5540-9.

^ "Prewetting with Salt Brine for More Effective Roadway Deicing". www.usroads.com.

^ ab "7 Ways to Dispose of Brine Waste". Desalitech. Retrieved 18 July 2017.

^ "Reverse Osmosis Desalination: Brine disposal". Lenntech. Retrieved 18 July 2017.