Boron trioxide

![Crystal structure of B2O3 [1]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d9/B2O3powder.JPG/220px-B2O3powder.JPG) | |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Other names boron oxide, diboron trioxide, boron sesquioxide, boric oxide, boria Boric acid anhydride | |

| Identifiers | |

CAS Number |

|

3D model (JSmol) |

|

ChEBI |

|

ChemSpider |

|

ECHA InfoCard | 100.013.751 |

EC Number | 215-125-8 |

PubChem CID |

|

RTECS number | ED7900000 |

InChI

| |

SMILES

| |

| Properties | |

Chemical formula | B2O3 |

Molar mass | 69.6182 g/mol |

| Appearance | white, glassy solid |

Density | 2.460 g/cm3, liquid; 2.55 g/cm3, trigonal; |

Melting point | 450 °C (842 °F; 723 K) (trigonal) 510 °C (tetrahedral) |

Boiling point | 1,860 °C (3,380 °F; 2,130 K) ,[2] sublimes at 1500 °C[3] |

Solubility in water | 1.1 g/100mL (10 °C) 3.3 g/100mL (20 °C) 15.7 100 g/100mL (100 °C) |

Solubility | partially soluble in methanol |

Acidity (pKa) | ~ 4 |

Magnetic susceptibility (χ) | -39.0·10−6 cm3/mol |

| Thermochemistry | |

Heat capacity (C) | 66.9 J/mol K |

Std molar entropy (S | 80.8 J/mol K |

Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH | -1254 kJ/mol |

Gibbs free energy (ΔfG˚) | -832 kJ/mol |

| Hazards | |

| Main hazards | Irritant[4] |

Safety data sheet | See: data page |

EU classification (DSD) (outdated) | Repr. Cat. 2 |

NFPA 704 |  0 2 0 |

Flash point | noncombustible |

| Lethal dose or concentration (LD, LC): | |

LD50 (median dose) | 3163 mg/kg (oral, mouse)[5] |

| US health exposure limits (NIOSH): | |

PEL (Permissible) | TWA 15 mg/m3[4] |

REL (Recommended) | TWA 10 mg/m3[4] |

IDLH (Immediate danger) | 2000 mg/m3[4] |

Supplementary data page | |

Structure and properties | Refractive index (n), Dielectric constant (εr), etc. |

Thermodynamic data | Phase behaviour solid–liquid–gas |

Spectral data | UV, IR, NMR, MS |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

Infobox references | |

Boron trioxide (or diboron trioxide) is one of the oxides of boron. It is a white, glassy solid with the formula B2O3. It is almost always found as the vitreous (amorphous) form; however, it can be crystallized after extensive annealing (that is, under prolonged heat).

Glassy boron oxide (g-B2O3) is thought to be composed of boroxol rings which are six-membered rings composed of alternating 3-coordinate boron and 2-coordinate oxygen. Because of the difficulty of building disordered models at the correct density with a large number of boroxol rings, this view was initially controversial, but such models have recently been constructed and exhibit properties in excellent agreement with experiment.[6] It is now recognized, from experimental and theoretical studies,[7][8][9][10][11] that the fraction of boron atoms belonging to boroxol rings in glassy B2O3 is somewhere between 0.73 and 0.83, with 0.75 (3⁄4) corresponding to a 1:1 ratio between ring and non-ring units.

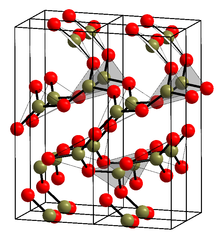

The crystalline form (α-B2O3) (see structure in the infobox[1]) is exclusively composed of BO3 triangles. This trigonal, quartz-like network undergoes a coesite-like transformation to monoclinic β-B2O3 at several gigapascals (9.5 GPa).[12]

Contents

1 Preparation

2 Applications

3 See also

4 References

5 External links

Preparation

Boron trioxide is produced by treating borax with sulfuric acid in a fusion furnace. At temperatures above 750 °C, the molten boron oxide layer separates out from sodium sulfate. It is then decanted, cooled and obtained in 96–97% purity.[3]

Another method is heating boric acid above ~300 °C. Boric acid will initially decompose into steam, (H2O(g)) and metaboric acid (HBO2) at around 170 °C, and further heating above 300 °C will produce more steam and boron trioxide. The reactions are:

- H3BO3 → HBO2 + H2O

- 2 HBO2 → B2O3 + H2O

Boric acid goes to anhydrous microcrystalline B2O3 in a heated fluidized bed.[13] Carefully controlled heating rate avoids gumming as water evolves. Molten boron oxide attacks silicates. Internally graphitized tubes via acetylene thermal decomposition are passivated.[14]

Crystallization of molten α-B2O3 at ambient pressure is strongly kinetically disfavored (compare liquid and crystal densities). Threshold conditions for crystallization of the amorphous solid are 10 kbar and ~200 °C.[15] Its proposed crystal structure in enantiomorphic space groups P31(#144); P32(#145)[16][17] (e.g., γ-glycine) has been revised to enantiomorphic space groups P3121(#152); P3221(#154)[18](e.g., α-quartz).

Boron oxide will also form when diborane (B2H6) reacts with oxygen in the air or trace amounts of moisture:

- 2B2H6(g) + 3O2(g) → 2B2O3(s) + 6H2(g)

- B2H6(g) + 3H2O(g) → B2O3(s) + 6H2(g)[19]

Applications

Fluxing agent for glass and enamels

- Starting material for synthesizing other boron compounds such as boron carbide

- An additive used in glass fibres (optical fibres)

- It is used in the production of borosilicate glass

- The inert capping layer in the Liquid Encapsulation Czochralski process for the production of gallium arsenide single crystal

- As an acid catalyst in organic synthesis

See also

- boron suboxide

- boric acid

- sassolite

- Tris(2,2,2-trifluoroethyl) borate

References

^ ab Gurr, G. E.; Montgomery, P. W.; Knutson, C. D.; Gorres, B. T. (1970). "The Crystal Structure of Trigonal Diboron Trioxide". Acta Crystallographica B. 26 (7): 906–915. doi:10.1107/S0567740870003369..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ High temperature corrosion and materials chemistry: proceedings of the Per Kofstad Memorial Symposium. Proceedings of the Electrochemical Society. The Electrochemical Society. 2000. p. 496. ISBN 1-56677-261-3.

^ ab Patnaik, P. (2003). Handbook of Inorganic Chemical Compounds. McGraw-Hill. p. 119. ISBN 0-07-049439-8. Retrieved 2009-06-06.

^ abcd "NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards #0060". National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

^ "Boron oxide". Immediately Dangerous to Life and Health Concentrations (IDLH). National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

^ Ferlat, G.; Charpentier, T.; Seitsonen, A. P.; Takada, A.; Lazzeri, M.; Cormier, L.; Calas, G.; Mauri. F. (2008). "Boroxol Rings in Liquid and Vitreous B2O3 from First Principles". Phys. Rev. Lett. 101: 065504. Bibcode:2008PhRvL.101f5504F. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.101.065504.; Ferlat, G.; Seitsonen, A. P.; Lazzeri, M.; Mauri, F. (2012). "Hidden polymorphs drive vitrification in B2O3". Nature Materials Letters. arXiv:1209.3482. Bibcode:2012NatMa..11..925F. doi:10.1038/NMAT3416.

^ Hung, I.; et al. (2009). "Determination of the bond-angle distribution in vitreous B2O3 by rotation (DOR) NMR spectroscopy". Journal of Solid State Chemistry. 182: 2402–2408. Bibcode:2009JSSCh.182.2402H. doi:10.1016/j.jssc.2009.06.025.

^ Soper, A. K. (2011). "Boroxol rings from diffraction data on vitreous boron trioxide". J. Phys.: Condens. Matter. 23: 365402. Bibcode:2011JPCM...23.5402S. doi:10.1088/0953-8984/23/36/365402.

^ Joo, C.; et al. (2000). "The ring structure of boron trioxide glass". Journal of Non-Crystalline Solids. 261: 282–286. Bibcode:2000JNCS..261..282J. doi:10.1016/s0022-3093(99)00609-2.

^ Zwanziger, J. W. (2005). "The NMR response of boroxol rings: a density functional theory study". Solid State Nuclear Magnetic Resonance. 27: 5–9. doi:10.1016/j.ssnmr.2004.08.004.

^ Micoulaut, M. (1997). "The structure of vitreous B2O3 obtained from a thermostatistical model of agglomeration". Journal of Molecular Liquids. 71: 107–114. doi:10.1016/s0167-7322(97)00003-2.

^ Brazhkin, V. V.; Katayama, Y.; Inamura, Y.; Kondrin, M. V.; Lyapin, A. G.; Popova, S. V.; Voloshin, R. N. (2003). "Structural transformations in liquid, crystalline and glassy B2O3 under high pressure". JETP Letters. 78 (6): 393–397. Bibcode:2003JETPL..78..393B. doi:10.1134/1.1630134.

^ Kocakuşak, S.; Akçay, K.; Ayok, T.; Koöroğlu, H. J.; Koral, M.; Savaşçi, Ö. T.; Tolun, R. (1996). "Production of anhydrous, crystalline boron oxide in fluidized bed reactor". Chemical Engineering and Processing. 35 (4): 311–317. doi:10.1016/0255-2701(95)04142-7.

^ Morelock, C. R. (1961). "Research Laboratory Report #61-RL-2672M". General Electric.

^ Aziz, M. J.; Nygren, E.; Hays, J. F.; Turnbull, D. (1985). "Crystal Growth Kinetics of Boron Oxide Under Pressure". Journal of Applied Physics. 57 (6): 2233. Bibcode:1985JAP....57.2233A. doi:10.1063/1.334368.

^ Gurr, G. E.; Montgomery, P. W.; Knutson, C. D.; Gorres, B. T. (1970). "The crystal structure of trigonal diboron trioxide". Acta Crystallographica B. 26 (7): 906–915. doi:10.1107/S0567740870003369.

^ Strong, S. L.; Wells, A. F.; Kaplow, R. (1971). "On the crystal structure of B2O3". Acta Crystallographica B. 27 (8): 1662–1663. doi:10.1107/S0567740871004515.

^ Effenberger, H.; Lengauer, C. L.; Parthé, E. (2001). "Trigonal B2O3 with Higher Space-Group Symmetry: Results of a Reevaluation". Monatshefte für Chemie. 132 (12): 1515–1517. doi:10.1007/s007060170008.

^ AirProducts (2011). "Diborane Storage & Delivery" (PDF).

External links

- National Pollutant Inventory: Boron and compounds

- Australian Government information

US NIH hazard information. See NIH.- Material Safety Data Sheet

- CDC - NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards - Boron oxide