German resistance to Nazism

It has been suggested that this article be split into articles titled German opposition to Nazism and German resistance to Hitler. (Discuss) (August 2018) |

Memorial plaque for resistance members and wreath at the Bendlerblock, Berlin.

The Memorial to Polish Soldiers and German Anti-Fascists 1939–1945 in Berlin.

German resistance to Nazism (German: Widerstand gegen den Nationalsozialismus) was the opposition by individuals and groups in Germany to the National Socialist regime between 1933 and 1945. Some of these engaged in active resistance with plans to remove Adolf Hitler from power by assassination and overthrow his regime.

The term German resistance should not be understood as meaning that there was a united resistance movement in Germany at any time during the Nazi period,[1] analogous to the more coordinated Polish Underground State, Greek Resistance, Yugoslav Partisans, French Resistance, Dutch Resistance, Norwegian resistance movement and Italian Resistance. The German resistance consisted of small and usually isolated groups. They were unable to mobilize political opposition. Except for individual attacks on Nazis (including Hitler) or sabotage acts, the only real strategy was to persuade leaders of the Wehrmacht to stage a coup against the regime: the 1944 assassination attempt against Hitler was intended to trigger such a coup.[1]

Approximately 77,000 German citizens were killed for one or another form of resistance by Special Courts, courts-martial, People's Courts and the civil justice system. Many of these Germans had served in government, the military, or in civil positions, which enabled them to engage in subversion and conspiracy; in addition, the Canadian historian Peter Hoffman counts unspecified "tens of thousands" in concentration camps who were either suspected of or actually engaged in opposition.[2] By contrast, the German historian Hans Mommsen wrote that resistance in Germany was "resistance without the people" and that the number of those Germans engaged in resistance to the Nazi regime was very small.[3] The resistance in Germany included German citizens of non-German ethnicity, such as members of the Polish minority who formed resistance groups like Olimp.[4]

Contents

1 Introduction

2 Pre-war resistance 1933–39

3 Role of the churches

3.1 Catholic resistance

3.2 Protestant churches

4 Resistance in the Army 1938–42

4.1 Munich crisis

4.2 Outbreak of war

5 First assassination attempt

6 Nadir of resistance: 1940–42

7 Communist resistance

8 Aeroplane assassination attempt

9 Suicide bombing attempts

10 After Stalingrad

11 The White Rose

12 Open Protest

13 Unorganized resistance

14 Relations with Allies

15 Towards July 20

16 20 July plot

17 Rastenburg

18 Aktion Rheinland

19 Historiography

20 See also

21 Notes

22 Further reading

23 External links

Introduction

The German opposition and resistance movements consisted of disparate political and ideological strands, which represented different classes of German society and were seldom able to work together – indeed for much of the period there was little or no contact between the different strands of resistance. A few civilian resistance groups developed, but the Army was the only organisation with the capacity to overthrow the government, and from within it a small number of officers came to present the most serious threat posed to the Nazi regime.[5] The Foreign Office and the Abwehr (Military Intelligence) also provided vital support to the movement.[6] But many of those in the military who ultimately chose to seek to overthrow Hitler had initially supported the regime, if not all of its methods. Hitler's 1938 purge of the military was accompanied by increased militancy in the Nazification of Germany, a sharp intensification of the persecution of Jews, homosexuals,[7] communists, socialists, and trade union leaders[8] and aggressive foreign policy, bringing Germany to the brink of war; it was at this time that the German Resistance emerged.[9]

Those opposing the Nazi regime were motivated by such factors as the mistreatment of Jews, harassment of the churches, and the harsh actions of Himmler and the Gestapo.[10] In his history of the German Resistance, Peter Hoffmann wrote that "National Socialism was not simply a party like any other; with its total acceptance of criminality it was an incarnation of evil, so that all those whose minds were attuned to democracy, Christianity, freedom, humanity or even mere legality found themselves forced into alliance...".[11]

Banned, underground political parties contributed one source of opposition. These included the Social Democrats (SPD)—with activist Julius Leber—Communists (KPD), and the anarcho-syndicalist group the Freie Arbeiter Union (FAUD), that distributed anti-Nazi propaganda and assisted people in fleeing the country.[12] Another group, the Red Orchestra (Rote Kapelle), consisted of anti-fascists, communists, and an American woman. The individuals in this group began to assist their Jewish friends as early as 1933.

Dietrich Bonhoeffer at Sigurdshof, 1939.

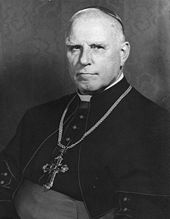

Christian churches, Catholic and Protestant, contributed another source of opposition. Their stance was symbolically significant. The churches, as institutions, did not openly advocate for the overthrow of the Nazi state, but they remained one of the very few German institutions to retain some independence from the state, and were thus able to continue to co-ordinate a level of opposition to Government policies. They resisted the regime's efforts to intrude on ecclesiastical autonomy, but from the beginning, a minority of clergymen expressed broader reservations about the new order, and gradually their criticisms came to form a "coherent, systematic critique of many of the teachings of National Socialism".[13] Some priests - such as the Jesuits Alfred Delp and Augustin Rösch and the Lutheran preacher Dietrich Bonhoeffer - were active and influential within the clandestine German Resistance, while figures such as Protestant Pastor Martin Niemöller (who founded the Confessing Church), and the Catholic Bishop August von Galen (who denounced Nazi euthanasia and lawlessness), offered some of the most trenchant public criticism of the Third Reich - not only against intrusions by the regime into church governance and to arrests of clergy and expropriation of church property, but also to the fundamentals of human rights and justice as the foundation of a political system.[14] Their example inspired some acts of overt resistance, such as that of the White Rose student group in Munich, and provided moral stimulus and guidance for various leading figures in the political Resistance.[15]

Individual Germans or small groups of people acting as the "unorganized resistance" defied the Nazi regime in various ways, most notably, those who helped Jews survive the Nazi Holocaust by hiding them, obtaining papers for them or in other ways aiding them. More than 300 Germans have been recognised for this.[16] It also included, particularly in the later years of the regime, informal networks of young Germans who evaded serving in the Hitler Youth and defied the cultural policies of the Nazis in various ways.

The German Army, the Foreign Office and the Abwehr, the military intelligence organization became sources for plots against Hitler in 1938 and again in 1939, but for a variety of reasons could not implement their plans. After the German defeat in the Battle of Stalingrad in 1943, they contacted many army officers who were convinced that Hitler was leading Germany to disaster, although fewer who were willing to engage in overt resistance. Active resisters in this group were frequently drawn from members of the Prussian aristocracy.

Almost every community in Germany had members taken away to concentration camps. As early as 1935 there were jingles warning:

"Dear Lord God, keep me quiet, so that I don't end up in Dachau." (It almost rhymes in German: Lieber Herr Gott mach mich stumm / Daß ich nicht nach Dachau komm.)[17] "Dachau" refers to the Dachau concentration camp. This is a parody of a common German children's prayer, "Lieber Gott mach mich fromm, daß ich in den Himmel komm." ("Dear God, keep me pious, so I go to Heaven")

Pre-war resistance 1933–39

Wilhelm Canaris, while a Korvettenkapitän

There was almost no organized resistance to Hitler's regime in the period between his appointment as chancellor on January 30, 1933, and the crisis over Czechoslovakia in early October 1938. By July 1933, all other political parties and the trade unions had been suppressed, the press and radio brought under state control, and most elements of civil society neutralised. The July 1933 Concordat between Germany and the Holy See ended any possibility of systematic resistance by the Catholic Church.[18] The largest Protestant church, the German Evangelical Church, was generally pro-Nazi, although a small number of church members resisted this position. The breaking of the power of the SA in the "Night of the Long Knives" in July 1934 ended any possibility of a challenge from the "socialist" wing of the Nazi Party, and also brought the army into closer alliance with the regime.[19]

Hitler's regime was overwhelmingly popular with the German people during this period. The failures of the Weimar Republic had discredited democracy in the eyes of most Germans. Hitler's apparent success in restoring full employment after the ravages of the Great Depression (achieved mainly through the reintroduction of conscription, a policy advocating that women stay home and raise children, a crash re-armament programme, and the incremental removal of Jews from the workforce as their jobs were tendered to Gentiles), and his bloodless foreign policy successes such as the reoccupation of the Rhineland in 1936 and the annexation of Austria in 1938, brought him almost universal acclaim.[19]

During this period, the SPD and the KPD managed to maintain underground networks, although the legacy of pre-1933 conflicts between the two parties meant that they were unable to co-operate. The Gestapo frequently infiltrated these networks, and the rate of arrests and executions of SPD and KPD activists was high, but the networks continued to be able recruit new members from the industrial working class, who resented the stringent labour discipline imposed by the regime during its race to rearm. The exiled SPD leadership in Prague received and published accurate reports of events inside Germany. But beyond maintaining their existence and fomenting industrial unrest, sometimes resulting in short-lived strikes, these networks were able to achieve little.[20]

There remained, however, a substantial base for opposition to Hitler's regime. Although the Nazi Party had taken control of the German state, it had not destroyed and rebuilt the state apparatus in the way the Bolshevik regime had done in the Soviet Union. Institutions such as the Foreign Office, the intelligence services and, above all, the army, retained some measure of independence, while outwardly submitting to the new regime. In May 1934, Colonel-General Ludwig Beck, Chief of Staff of the Army, had offered to resign if preparations were made for an offensive war against Czechoslovakia.[21] The independence of the army was eroded in 1938, when both the War Minister, General Werner von Blomberg, and the Army Chief, General Werner von Fritsch, were removed from office, but an informal network of officers critical of the Nazi regime remained.[19]

In 1936, thanks to an informer, the Gestapo raids devastated Anarcho-syndicalist groups all over Germany, resulting in the arrest of 89 people. Most ended up either imprisoned or murdered by the regime. The groups had been encouraging strikes, printing and distributing anti-Nazi propaganda and recruiting people to fight the Nazis' fascist allies during the Spanish Civil War.[12]

As part of the agreement with the conservative forces by which Hitler became chancellor in 1933, the non-party conservative Konstantin von Neurath remained foreign minister, a position he retained until 1938. During Neurath's time in control, the Foreign Office with its network of diplomats and access to intelligence, became home to a circle of resistance, under the discreet patronage of the Under-Secretary of State Ernst von Weizsäcker.[22] Prominent in this circle were the ambassador in Rome Ulrich von Hassell, the Ambassador in Moscow Friedrich Graf von der Schulenburg, and officials Adam von Trott zu Solz, Erich Kordt and Hans Bernd von Haeften. This circle survived even when the ardent Nazi Joachim von Ribbentrop succeeded Neurath as foreign minister.[23]

The most important centre of opposition to the regime within the state apparatus was in the intelligence services, whose clandestine operations offered an excellent cover for political organisation. The key figure here was Colonel Hans Oster, head of the Military Intelligence Office from 1938, and an anti-Nazi from as early as 1934.[24] He was protected by the Abwehr chief Admiral Wilhelm Canaris.[25] Oster organized an extensive clandestine network of potential resisters in the army and the intelligence services. He found an early ally in Hans Bernd Gisevius, a senior official in the Interior Ministry. Hjalmar Schacht, the governor of the Reichsbank, was also in touch with this opposition.[26]

The problem these groups faced, however, was what form resistance to Hitler could take in the face of the regime's successive triumphs. They recognised that it was impossible to stage any kind of open political resistance. This was not, as is sometimes stated, because the repressive apparatus of the regime was so all-pervasive that public protest was impossible – as was shown when Catholics protested against the removal of crucifixes from Oldenburg schools in 1936, and the regime backed down. Rather it was because of Hitler's massive support among the German people. While resistance movements in the occupied countries could mobilise patriotic sentiment against the German occupiers, in Germany the resistance risked being seen as unpatriotic, particularly in wartime. Even many army officers and officials who detested Hitler had a deep aversion to being involved in "subversive" or "treasonous" acts against the government.[24][27]

As early as 1936, Oster and Gisevius came to the view that a regime so totally dominated by one man could only be brought down by eliminating that man – either by assassinating Hitler or by staging an army coup against him. However, it was a long time before any significant number of Germans came to accept this view. Many clung to the belief that Hitler could be persuaded to moderate his regime, or that some other more moderate figure could replace him. Others argued that Hitler was not to blame for the regime's excesses, and that the removal of Heinrich Himmler and reduction in the power of the SS was needed. Some oppositionists were devout Christians who disapproved of assassination as a matter of principle. Others, particularly the army officers, felt bound by the personal oath of loyalty they had taken to Hitler in 1934.[24]

The opposition was also hampered by a lack of agreement about their objectives other than the need to remove Hitler from power. Some oppositionists were liberals who opposed the ideology of the Nazi regime in its entirety, and who wished to restore a system of parliamentary democracy. Most of the army officers and many of the civil servants, however, were conservatives and nationalists, and many had initially supported Hitler's policies – Carl Goerdeler, the Lord Mayor of Leipzig, was a good example. Some favored restoring the Hohenzollern dynasty, while others favored an authoritarian, but not Nazi, regime. Some saw no problem with Hitler's anti-Semitism and ultra-nationalism, and opposed only his apparent reckless determination to take Germany into a new world war. Because of their many differences, the opposition was unable to form a united movement, or to send a coherent message to potential allies outside Germany.[19]

Role of the churches

Though neither the Catholic nor Protestant churches as institutions were prepared to openly oppose the Nazi State, it was from the clergy that the first major component of the German Resistance to the policies of the Third Reich emerged, and the churches as institutions provided the earliest and most enduring centres of systematic opposition to Nazi policies. From the outset of Nazi rule in 1933, issues emerged which brought the churches into conflict with the regime.[28] They offered organised, systematic and consistent resistance to government policies which infringed on ecclesiastical autonomy.[29] As one of the few German institutions to retain some independence from the state, the churches were able to co-ordinate a level of opposition to Government, and, according to Joachim Fest, they, more than any other institutions, continued to provide a "forum in which individuals could distance themselves from the regime".[30] Christian morality and the anti-Church policies of the Nazis also motivated many German resisters and provided impetus for the "moral revolt" of individuals in their efforts to overthrow Hitler.[31] The historian Wolf cites events such as the July Plot of 1944 as having been "inconceivable without the spiritual support of church resistance".[28][32]

"From the very beginning", wrote Hamerow, "some churchmen expressed, quite directly at times, their reservations about the new order. In fact those reservations gradually came to form a coherent, systematic critique of many of the teachings of National Socialism."[13] Clergy in the German Resistance had some independence from the state apparatus, and could thus criticise it, while not being close enough to the centre of power to take steps to overthrow it. "Clerical resistors", wrote Theodore S. Hamerow, could indirectly "articulate political dissent in the guise of pastoral stricture". They usually spoke out not against the established system, but "only against specific policies that it had mistakenly adopted and that it should therefore properly correct".[33] Later, the most trenchant public criticism of the Third Reich came from some of Germany's religious leaders, as the government was reluctant to move against them, and though they could claim to be merely attending to the spiritual welfare of their flocks, "what they had to say was at times so critical of the central doctrines of National Socialism that to say it required great boldness", and they became resistors. Their resistance was directed not only against intrusions by the government into church governance and to arrests of clergy and expropriation of church property, but also to matters like Nazi euthanasia and eugenics and to the fundamentals of human rights and justice as the foundation of a political system.[14] A senior cleric could rely on a degree of popular support from the faithful, and thus the regime had to consider the possibility of nationwide protests if such figures were arrested.[13] Thus the Catholic Bishop of Munster, August von Galen and Dr Theophil Wurm, the Protestant Bishop of Wurttemberg were able to rouse widespread public opposition to murder of invalids.[34]

For figures like the Jesuit Provincial of Bavaria, Augustin Rösch, the Catholic trade unionists Jakob Kaiser and Bernhard Letterhaus and the July Plot leader Claus von Stauffenberg, "religious motives and the determination to resist would seem to have developed hand in hand".[35] Ernst Wolf wrote that some credit must be given to the resistance of the churches, for providing "moral stimulus and guidance for the political Resistance...".[36] Virtually all of the military conspirators in the July Plot were religious men.[37] Among the social democrat political conspirators, the Christian influence was also strong, though humanism also played a significant foundational role - and among the wider circle there were other political, military and nationalist motivations at play.[37] Religious motivations were particularly strong in the Kreisau Circle of the Resistance.[38] The Kreisau leader Helmuth James Graf von Moltke declared in one of his final letters before execution that the essence of the July revolt was "outrage of the Christian conscience".[32]

In the words of Kershaw, the churches "engaged in a bitter war of attrition with the regime, receiving the demonstrative backing of millions of churchgoers. Applause for Church leaders whenever they appeared in public, swollen attendances at events such as Corpus Christi Day processions, and packed church services were outward signs of the struggle of... especially of the Catholic Church - against Nazi oppression". While the Church ultimately failed to protect its youth organisations and schools, it did have some successes in mobilizing public opinion to alter government policies.[39] The churches challenged Nazi efforts to undermine various Christian institutions, practices and beliefs and Bullock wrote that "among the most courageous demonstrations of opposition during the war were the sermons preached by the Catholic Bishop of Munster and the Protestant Pastor, Dr Niemoller..." but that nevertheless, "Neither the Catholic Church nor the Evangelical Church... as institutions, felt it possible to take up an attitude of open opposition to the regime".[40]

Catholic resistance

| Part of a series on |

Persecutions of the Catholic Church |

|---|

Overview

|

Roman Empire

|

Neo-Persian Empire

|

Byzantine Empire

|

Islamic world

|

Japan

|

European wars of religion

|

France

|

Mexico

|

Spain

|

Netherlands Titus Brandsma |

Germany

|

China

|

Vietnam

|

Poland

|

Eastern Europe

|

India

|

Nicaragua

|

El Salvador

|

Nigeria Religious violence in Nigeria |

Guatemala

|

In the 1920s and 1930s, the main Christian opposition to Nazism had come from the Catholic Church.[41] German bishops were hostile to the emerging movement and energetically denounced its "false doctrines".[42][43] A threatening, though initially mainly sporadic persecution of the Catholic Church in Germany followed the Nazi takeover.[44] Hitler moved quickly to eliminate Political Catholicism, rounding up members of the Catholic political parties and banning their existence in July 1933. Vice Chancellor Franz von Papen, the leader of the Catholic right-wing, meanwhile negotiated a Reich concordat with the Holy See, which prohibited clergy from participating in politics.[45] Catholic resistance initially diminished after the Concordat, with Cardinal Bertram of Breslau, the chairman of the German Conference of Bishops, developing an ineffectual protest system.[30] Firmer resistance by Catholic leaders gradually reasserted itself by the individual actions of leading churchmen like Josef Frings, Konrad von Preysing, August von Galen and Michael von Faulhaber. Most Catholic opposition to the regime came from the Catholic left-wing in the Christian trade unions, such as by the union leaders Jakob Kaiser and (Blessed) Nikolaus Gross. Hoffmann writes that, from the beginning:[28]

.mw-parser-output .templatequote{overflow:hidden;margin:1em 0;padding:0 40px}.mw-parser-output .templatequote .templatequotecite{line-height:1.5em;text-align:left;padding-left:1.6em;margin-top:0}

"[The Catholic Church] could not silently accept the general persecution, regimentation or oppression, nor in particular the sterilization law of summer 1933. Over the years until the outbreak of war Catholic resistance stiffened until finally its most eminent spokesman was the Pope himself with his encyclial Mit brennender Sorge... of 14 March 1937, read from all German Catholic pulpits. Clemens August Graf von Galen, Bishop of Munster, was typical of the many fearless Catholic speakers. In general terms, therefore, the churches were the only major organisations to offer comparatively early and open resistance: they remained so in later years.

— Extract from The History of the German Resistance 1933-1945 by Peter Hoffmann

Erich Klausener, the head of Catholic Action, was assassinated in Hitler's bloody night of the long knives purge of 1934.[46]

In the year following Hitler's "seizure of power", old political players looked for means to overthrow the new government.[47] The former Catholic Centre Party leader and Reich Chancellor Heinrich Brüning looked for a way to oust Hitler.[48]Erich Klausener, an influential civil servant and president of Berlin's Catholic Action group organised Catholic conventions in Berlin in 1933, and 1934 and spoke against political oppression to a crowd of 60,000 at the 1934 rally.[49] Deputy Reich Chancellor von Papen, a conservative Catholic nobleman, delivered an indictment of the Nazi government in his Marburg speech of 17 June.[48][50] His speech writer Edgar Jung, a Catholic Action worker, seized the opportunity to reassert the Christian foundation of the state, pleaded for religious freedom, and rejected totalitarian aspirations in the field of religion, hoping to spur a rising, centred on Hindenberg, Papen and the army.[51]

Hitler decided to strike at his chief political opponents in the Night of the Long Knives. The purge lasted two days over 30 June and 1 July 1934.[52] Leading rivals of Hitler were killed. High-profile Catholic resistors were targeted - Klausener and Jung were murdered.[53]Adalbert Probst, the national director of the Catholic Youth Sports Association, was also killed.[54][55][55] The Catholic press was targeted too, with anti-Nazi journalist Fritz Gerlich among the dead.[56] On 2 August 1934, the aged President von Hindenberg died. The offices of President and Chancellor were combined, and Hitler ordered the Army to swear an oath directly to him. Hitler declared his "revolution" complete.[57]

Cardinal Michael von Faulhaber gained an early reputation as a critic of the Nazis.[58] His three Advent sermons of 1933, entitled Judaism, Christianity, and Germany denounced the Nazi extremists who were calling for the Bible to be purged of the "Jewish" Old Testament.[59] Faulhaber tried to avoid conflict with the state over issues not strictly pertaining to the church, but on issues involving the defence of Catholics he refused to compromise or retreat.[60] When in 1937 the authorities in Upper Bavaria attempted to replace Catholic schools with "common schools", he offered fierce resistance.[60] Among the most firm and consistent of senior Catholics to oppose the Nazis was Konrad von Preysing, Bishop of Berlin from 1935.[61] He worked with leading members of the resistance Carl Goerdeler an Helmuth James Graf von Moltke. He was part of the five-member commission that prepared the Mit brennender Sorge anti-Nazi encyclical of March 1937, and sought to block the Nazi closure of Catholic schools and arrests of church officials.[62][63]

While Hitler did not feel powerful enough to arrest senior clergy before the end of the war, an estimated one third of German priests faced some form of reprisal from the Nazi Government and 400 German priests were sent to the dedicated Priest Barracks of Dachau Concentration Camp alone. Among the best known German priest martyrs were the Jesuit Alfred Delp and Fr Bernhard Lichtenberg.[39] Lichtenberg ran Bishop von Preysing's aid unit (the Hilfswerke beim Bischöflichen Ordinariat Berlin) which secretly assisted those who were being persecuted by the regime. Arrested in 1941, he died en route to Dachau Concentration Camp in 1943.[64] Delp - along with fellow Jesuits Augustin Rösch and Lothar König - was among the central players of the Kreisau Circle Resistance group.[65] Bishop von Preysing also had contact with the group.[66] The group combined conservative notions of reform with socialist strains of thought - a symbiosis expressed by Delp's notion of "personal socialism".[67] Among the German laity, Gertrud Luckner, was among the first to sense the genocidal inclinations of the Hitler regime and to take national action.[68] She cooperated with Lichtenberg and Delp and attempted to establish a national underground network to assist Jews through the Catholic aid agency Caritas.[68] Using international contacts she secured safe passage abroad for many refugees. She organized aid circles for Jews, assisted many to escape.[69] Arrested in 1943, she only narrowly escaped death in the concentration camps.[68] Social worker Margarete Sommer counselled victims of racial persecution for Caritas Emergency Relief and in 1941 became director of the Welfare Office of the Berlin Diocesan Authority, under Lichtenberg, and Bishop Preysing. She coordinated Catholic aid for victims of racial persecution - giving spiritual comfort, food, clothing, and money and wrote several reports on the mistreatment of Jews from 1942, including an August 1942 report which reached Rome under the title “Report on the Exodus of the Jews”.[70]

The Blessed Clemens August Graf von Galen, Bishop of Munster, condemned Nazi policies from the pulpit.

Even at the height of Hitler's popularity, one issue unexpectedly provoked powerful and successful resistance to his regime. This was the programme of so-called “euthanasia” – in fact a campaign of mass murder – directed at people with mental illness and/or severe physical disabilities which had begun in 1939 under the code name T4. By 1941, more than 70,000 people had been killed under this programme, many by gassing, and their bodies incinerated. This policy aroused strong opposition across German society, and especially among Catholics. Opposition to the policy sharpened after the German attack on the Soviet Union in June 1941, because the war in the east produced for the first time large-scale German casualties, and the hospitals and asylums began to fill up with maimed and disabled young German soldiers. Rumours began to circulate that these men would also be subject to “euthanasia,” although no such plans existed.

Catholic anger was further fuelled by actions of the Gauleiter of Upper Bavaria, Adolf Wagner, a militantly anti-Catholic Nazi, who in June 1941 ordered the removal of crucifixes from all schools in his Gau. This attack on Catholicism provoked the first public demonstrations against government policy since the Nazis had come to power, and the mass signing of petitions, including by Catholic soldiers serving at the front. When Hitler heard of this he ordered Wagner to rescind his decree, but the damage had been done – German Catholics had learned that the regime could be successfully opposed. This led to more outspoken protests against the “euthanasia” programme.

In July, the Bishop of Münster, August von Galen (an old aristocratic conservative, like many of the anti-Hitler Army officers), publicly denounced the “euthanasia” programme in a sermon, and telegrammed his text to Hitler, calling on “the Führer to defend the people against the Gestapo.” Another Bishop, Franz Bornewasser of Trier, also sent protests to Hitler, though not in public. On 3 August, von Galen was even more outspoken, broadening his attack to include the Nazi persecution of religious orders and the closing of Catholic institutions. Local Nazis asked for Galen to be arrested, but Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels told Hitler that if this happened there would be an open revolt in Westphalia. Galen's sermons went further than defending the church, he spoke of a moral danger to Germany from the regime's violations of basic human rights: "the right to life, to inviolability, and to freedom is an indispensable part of any moral social order", he said - and any government that punishes without court proceedings "undermines its own authority and respect for its sovereignty within the conscience of its citizens".[71]

By August, the protests had spread to Bavaria. Hitler was jeered by an angry crowd at Hof, near Nuremberg – the only time he was opposed to his face in public during his 12 years of rule.[72] Hitler knew that he could not afford a confrontation with the Church at a time when Germany was engaged in a life-and-death two-front war. (It needs to be remembered that following the annexations of Austria and the Sudetenland, nearly half of all Germans were Catholic.) On 24 August he ordered the cancellation of the T4 programme and issued strict instructions to the Gauleiters that there were to be no further provocations of the churches during the war.

Pius XII became Pope on the eve of World War II, and maintained links to the German Resistance. Although remaining publicly neutral, Pius advised the British in 1940 of the readiness of certain German generals to overthrow Hitler if they could be assured of an honourable peace, offered assistance to the German resistance in the event of a coup and warned the Allies of the planned German invasion of the Low Countries in 1940.[73][74][75] In 1943, Pius issued the Mystici corporis Christi encyclical, in which he condemned the practice of killing the disabled. He stated his "profound grief" at the murder of the deformed, the insane, and those suffering from hereditary disease... as though they were a useless burden to Society", in condemnation of the ongoing Nazi euthanasia program. The Encyclical was followed, on 26 September 1943, by an open condemnation by the German Bishops which, from every German pulpit, denounced the killing of "innocent and defenceless mentally handicapped, incurably infirm and fatally wounded, innocent hostages, and disarmed prisoners of war and criminal offenders, people of a foreign race or descent".[76]

However, the deportation of Polish and Dutch priests by the occupying Nazis by 1942 — after Polish resistance acts and the Dutch Catholic bishops' conference's official condemnation of anti-Semitic persecutions and deportations of Jews by the Nazis — also terrified ethnic German clergy in Germany itself, some of whom would come to share the same fate because of their resistance against the Nazi government in racial and social aspects, among them Fr. Bernhard Lichtenberg. Himmler's 1941 Aktion Klostersturm (Operation Attack-the-Monastery) had also helped to spread fear among regime-critical Catholic clergy.[77][78]

Protestant churches

Following the Nazi takeover, Hitler attempted the subjugation of the Protestant churches under a single Reich Church. He divided the Lutheran Church (Germany's main Protestant denomination) and instigated a brutal persecution of Jehovah's Witnesses, who refused military service and allegiance to Hitlerism.[79] Pastor Martin Niemöller responded with the Pastors Emergency League which re-affirmed the Bible. The movement grew into the Confessing Church, from which some clergymen opposed the Nazi regime.[80] By 1934, the Confessional Church had declared itself the legitimate Protestant Church of Germany.[81] In response to the regime's attempt to establish a state church, in March 1935, the Confessing Church Synod announced:[82]

We see our nation threatened with mortal danger; the danger lies in a new religion. The Church has been ordered by its Master to see that Christ is honoured by our nation in a manner befitting the Judge of the world. The Church knows that it will be called to account if the German nation turns its back on Christ without being forewarned".

— 1935 Confessing Church Synod

In May 1936, the Confessing Church sent Hitler a memorandum courteously objecting to the "anti-Christian" tendencies of his regime, condemning anti-Semitism and asking for an end to interference in church affairs.[81] Paul Berben wrote, "A Church envoy was sent to Hitler to protest against the religious persecutions, the concentration camps, and the activities of the Gestapo, and to demand freedom of speech, particularly in the press."[82] The Nazi Minister of the Interior, Wilhelm Frick responded harshly. Hundreds of pastors were arrested; Dr Weissler, a signatory to the memorandum, was killed at Sachsenhausen concentration camp and the funds of the church were confiscated and collections forbidden.[81] Church resistance stiffened and by early 1937, Hitler had abandoned his hope of uniting the Protestant churches.[82]

The Confessing Church was banned on 1 July 1937. Niemöller was arrested by the Gestapo, and sent to the concentration camps. He remained mainly at Dachau until the fall of the regime. Theological universities were closed, and other pastors and theologians arrested.[82]

Dietrich Bonhoeffer, another leading spokesman for the Confessing Church, was from the outset a critic of the Hitler regime's racism and became active in the German Resistance – calling for Christians to speak out against Nazi atrocities. Arrested in 1943, he was implicated in the 1944 July Plot to assassinate Hitler and executed.[83]

Resistance in the Army 1938–42

Despite the removal of Blomberg and Fritsch, the army retained considerable independence, and senior officers were able to discuss their political views in private fairly freely. In May 1938, the army leadership was made aware of Hitler's intention of invading Czechoslovakia, even at the risk of war with Britain, France, and/or the Soviet Union. The Army Chief of Staff, General Ludwig Beck, regarded this as not only immoral but reckless, since he believed that Germany would lose such a war. Oster and Beck sent emissaries to Paris and London to advise the British and French to resist Hitler's demands, and thereby strengthen the hand of Hitler's opponents in the Army. Weizsäcker also sent private messages to London urging resistance. The British and French were extremely doubtful of the ability of the German opposition to overthrow the Nazi regime and ignored these messages. An official of the British Foreign Office wrote on August 28, 1938: "We have had similar visits from other emissaries of the Reichsheer, such as Dr. Goerdeler, but those for whom these emissaries claim to speak have never given us any reasons to suppose that they would be able or willing to take action such as would lead to the overthrow of the regime. The events of June 1934 and February 1938 do not lead one to attach much hope to energetic action by the Army against the regime"[84] Because of the failure of Germans to overthrow their Führer in 1938, the British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain was convinced that the resistance comprised a group of people seemingly not well organized.[85]

Writing of the 1938 conspiracy, the German historian Klaus-Jürgen Müller observed that the conspiracy was a loosely organized collection of two different groups. One group comprising the army's Chief of Staff General Ludwig Beck, the Abwehr chief, Admiral Wilhelm Canaris, and the Foreign Office's State Secretary, Baron Ernst von Weizsäcker were the "anti-war" group in the German government, which was determined to avoid a war in 1938 that it felt Germany would lose. This group was not committed to the overthrow of the regime but was loosely allied to another, more radical group, the "anti-Nazi" fraction centered on Colonel Hans Oster and Hans Bernd Gisevius, which wanted to use the crisis as an excuse for executing a putsch to overthrow the Nazi regime.[86] The divergent aims between these two factions produced considerable tensions.[87] The historian Eckart Conze in a 2010 interview stated about the "anti-war" group in 1938:

"An overthrow of Hitler was out of the question. The group wanted to avoid a major war and the potential catastrophic consequences for Germany. Their goal wasn't to get rid of the dictator but, as they saw it, to bring him to his senses."[88]

In August, Beck spoke openly at a meeting of army generals in Berlin about his opposition to a war with the western powers over Czechoslovakia. When Hitler was informed of this, he demanded and received Beck's resignation. Beck was highly respected in the army and his removal shocked the officer corps. His successor as chief of staff, Franz Halder, remained in touch with him, and was also in touch with Oster. Privately, he said that he considered Hitler "the incarnation of evil".[89] During September, plans for a move against Hitler were formulated, involving General Erwin von Witzleben, who was the army commander of the Berlin Military Region and thus well-placed to stage a coup.

Oster, Gisevius, and Schacht urged Halder and Beck to stage an immediate coup against Hitler, but the army officers argued that they could only mobilize support among the officer corps for such a step if Hitler made overt moves towards war. Halder nevertheless asked Oster to draw up plans for a coup. Weizsäcker and Canaris were made aware of these plans. The conspirators disagreed on what to do about Hitler if there was a successful army coup – eventually most overcame their scruples and agreed that he must be killed so that army officers would be free from their oath of loyalty. They agreed Halder would instigate the coup when Hitler committed an overt step towards war. During the planning for the 1938 putsch, Carl Friedrich Goerdeler was in contact through the intermediary of General Alexander von Falkenhausen with Chinese intelligence[90] Most German conservatives favoured Germany's traditional informal alliance with China, and were strongly opposed to the about-face in Germany's Far Eastern policies effected in early 1938 by Joachim von Ribbentrop, who abandoned the alliance with China for an alignment with Japan.[90] As a consequence, agents of Chinese intelligence supported the proposed putsch as a way of restoring the Sino-German alliance.[90]

Remarkably, the army commander, General Walther von Brauchitsch, was well aware of the coup preparations. He told Halder he could not condone such an act, but he did not inform Hitler, to whom he was outwardly subservient, of what he knew.[91] This was a striking example of the code of silent solidarity among senior German Army officers, which was to survive and provide a shield for the resistance groups down to, and in many cases beyond, the crisis of July 1944.

Munich crisis

From left to right, Neville Chamberlain, Édouard Daladier, Adolf Hitler, Benito Mussolini and Italian Foreign Minister Count Ciano as they prepare to sign the Munich Agreement

On 13 September, the British Prime Minister, Neville Chamberlain, announced that he would visit Germany to meet Hitler and defuse the crisis over Czechoslovakia. This threw the conspirators into uncertainty. When, on 20 September, it appeared that the negotiations had broken down and that Chamberlain would resist Hitler's demands, the coup preparations were revived and finalised. All that was required was the signal from Halder.

On 28 September, however, Chamberlain backed down and agreed to a meeting in Munich, at which he accepted the dismemberment of Czechoslovakia. This plunged the resistance into demoralisation and division. Halder said he would no longer support a coup. The other conspirators were bitterly critical of Chamberlain, but were powerless to act. This was the nearest approach to a successful conspiracy against Hitler before the plot of 20 July 1944.

As war again grew more likely in mid-1939, the plans for a pre-emptive coup were revived. Oster was still in contact with Halder and Witzleben, although Witzleben had been transferred to Frankfurt am Main, reducing his ability to lead a coup attempt. At a meeting with Goerdeler, Witzleben agreed to form a network of army commanders willing to take part to prevent a war against the western powers. But support in the officer corps for a coup had dropped sharply since 1938. Most officers, particularly those from Prussian landowning backgrounds, were strongly anti-Polish. Just before the invasion of Poland in August 1939, General Eduard Wagner who was one of the officers involved in the abortive putsch of September 1938, wrote in a letter to his wife: “We believe we will make quick work of the Poles, and in truth, we are delighted at the prospect. That business must be cleared up" (Emphasis in the original)[92] The German historian Andreas Hillgruber commented that in 1939 the rampant anti-Polish feelings in the German Army officer corps served to bind the military together with Hitler in supporting Fall Weiss in a way that Fall Grün did not.[92]

This nevertheless marked an important turning point. In 1938, the plan had been for the army, led by Halder and if possible Brauchitsch, to depose Hitler. This was now impossible, and a conspiratorial organisation was to be formed in the army and civil service instead.

The opposition again urged Britain and France to stand up to Hitler: Halder met secretly with the British Ambassador Sir Nevile Henderson to urge resistance. The plan was again to stage a coup at the moment Hitler moved to declare war. However, although Britain and France were now prepared to go to war over Poland, as war approached, Halder lost his nerve. Schacht, Gisevius and Canaris developed a plan to confront Brauchitsch and Halder and demand that they depose Hitler and prevent war, but nothing came of this. When Hitler invaded Poland on 1 September, the conspirators were unable to act.

Outbreak of war

The outbreak of war made the further mobilization of resistance in the army more difficult. Halder continued to vacillate. In late 1939 and early 1940 he opposed Hitler's plans to attack France, and kept in touch with the opposition through General Carl-Heinrich von Stülpnagel, an active oppositionist. Talk of a coup again began to circulate, and for the first time the idea of killing Hitler with a bomb was taken up by the more determined members of the resistance circles, such as Oster and Erich Kordt, who declared himself willing to do the deed. At the army headquarters at Zossen, south of Berlin, a group of officers called Action Group Zossen was also planning a coup.

When in November 1939 it seemed that Hitler was about to order an immediate attack in the west, the conspirators persuaded General Wilhelm Ritter von Leeb, commander of Army Group C on the Belgian border, to support a planned coup if Hitler gave such an order. At the same time Oster warned the Dutch and the Belgians that Hitler was about to attack them – his warnings were not believed. But when Hitler postponed the attack until 1940, the conspiracy again lost momentum, and Halder formed the view that the German people would not accept a coup. Again, the chance was lost.

With Poland overrun but France and the Low Countries yet to be attacked, the German Resistance sought the Pope's assistance in preparations for a coup to oust Hitler.[93] In the winter of 1939/40, the Bavarian lawyer and reserve 'Abwehr' officer Josef Müller, acting as an emissary for the military opposition centered around General Franz Halder, contacted Monsignore Ludwig Kaas, the exiled leader of the German Catholic Zentrum party, in Rome, hoping to use the Pope as an intermediary to contact the British.[94] Kaas put Müller in contact with Father Robert Leiber, who personally asked the Pope to relay the information about the German resistance to the British.[95]

The Vatican considered Müller to be a representative of Colonel-General von Beck and agreed to offer the machinery for mediation.[96][97] Oster, Wilhelm Canaris and Hans von Dohnányi, backed by Beck, told Müller to ask Pius to ascertain whether the British would enter negotiations with the German opposition which wanted to overthrow Hitler. The British agreed to negotiate, provided the Vatican could vouch for the opposition's representative. Pius, communicating with Britain's Francis d'Arcy Osborne, channelled communications back and forth in secrecy.[96] The Vatican agreed to send a letter outlining the bases for peace with England and the participation of the Pope was used to try to persuade senior German Generals Halder and Brauchitsch to act against Hitler.[93] Negotiations were tense, with a Western offensive expected, and on the basis that substantive negotiations could only follow the replacement of the Hitler regime.[96] Pius, without offering endorsement, advised Osbourne on 11 January 1940 that the German opposition had said that a German offensive was planned for February, but that this could be averted if the German generals could be assured of peace with Britain, and not on punitive terms. If this could be assured, then they were willing to move to replace Hitler. The British government had doubts as to the capacity of the conspirators. On 7 February, the Pope updated Osbourne that the opposition wanted to replace the Nazi regime with a democratic federation, but hoped to retain Austria and the Sudetenland. The British government was non-committal, and said that while the federal model was of interest, the promises and sources of the opposition were too vague. Nevertheless, the resistance were encouraged by the talks, and Muller told his contact that a coup would occur in February. Pius appeared to continue to hope for a coup in Germany into March 1940.[98]

Following the Fall of France, peace overtures continued to emanate from the Vatican as well as Sweden and the United States, to which Churchill responded resolutely that Germany would first have to free its conquered territories.[99] The negotiations ultimately proved fruitless. Hitler's swift victories over France and the Low Countries deflated the will of the German military to resist Hitler. Muller was arrested during the Nazis first raid on Military Intelligence in 1943. He spent the rest of the war in concentration camps, ending up at Dachau.[100]

The failed plots of 1938 and 1939 showed both the strength and weakness of the officer corps as potential leaders of a resistance movement. Its strength was its loyalty and solidarity. As Istvan Deak noted: "Officers, especially of the highest ranks, had been discussing, some as early as 1934 ... the possibility of deposing or even assassinating Hitler. Yet it seems that not a single one was betrayed by a comrade-in-arms to the Gestapo."[101] Remarkably, in over two years of plotting, this widespread and loosely structured conspiracy was never detected. One explanation is that at this time Himmler was still preoccupied with the traditional enemies of the Nazis, the SPD and the KPD (and, of course, the Jews), and did not suspect that the real centre of opposition was within the state itself. Another factor was Canaris’ success in shielding the plotters, particularly Oster, from suspicion.

The corresponding weakness of the officer corps was its conception of loyalty to the state and its aversion to mutiny. This explains the vacillations of Halder, who could never quite bring himself to take the decisive step. Halder hated Hitler, and believed that the Nazis were leading Germany to catastrophe. He was shocked and disgusted by the behaviour of the SS in occupied Poland, but gave no support to his senior officer there, General Johannes Blaskowitz, when the latter officially protested to Hitler about the atrocities against the Poles and the Jews. In 1938 and again in 1939, he lost his nerve and could not give the order to strike against Hitler. This was even more true of Brauchitsch, who knew of the conspiracies and assured Halder that he agreed with their objectives, but would not take any action to support them.

The outbreak of war served to rally the German people around the Hitler regime, and the sweeping early successes of the German Army – occupying Poland in 1939, Denmark and Norway in April 1940, and swiftly defeating France in May and June 1940, stilled virtually all opposition to the regime. The opposition to Hitler within the Army was left isolated and apparently discredited, since the much-feared war with the western powers had apparently been won by Germany within a year and at little cost. This mood continued well into 1941, although beneath the surface popular discontent at mounting economic hardship was apparent.

First assassination attempt

Ruins of the Bürgerbräukeller in Munich after Georg Elser's failed assassination of Hitler in November 1939

In November 1939, Georg Elser, a carpenter from Württemberg, developed a plan to assassinate Hitler completely on his own. Elser had been peripherally involved with the KPD before 1933, but his exact motives for acting as he did remain a mystery. He read in the newspapers that Hitler would be addressing a Nazi Party meeting on 8 November, in the Bürgerbräukeller, a beer hall in Munich where Hitler had launched the Beer Hall Putsch on the same date in 1923. Stealing explosives from his workplace, he built a powerful time bomb, and for over a month managed to stay inside the Bürgerbräukeller after hours each night, during which time he hollowed out the pillar behind the speaker's rostrum to place the bomb inside.

On the night of 7 November 1939, Elser set the timer and left for the Swiss border. Unexpectedly, because of the pressure of wartime business, Hitler made a much shorter speech than usual and left the hall 13 minutes before the bomb went off, killing seven people. Sixty-three people were injured, sixteen more were seriously injured with one dying later. Had Hitler still been speaking, the bomb almost certainly would have killed him.

This event set off a hunt for potential conspirators which intimidated the opposition and made further action more difficult. Elser was arrested at the border, sent to the Sachsenhausen Concentration Camp, and then in 1945 moved to the Dachau concentration camp; he was executed two weeks before the liberation of Dachau KZ.

Nadir of resistance: 1940–42

The sweeping success of Hitler's attack on France in May 1940 made the task of deposing him even more difficult. Most army officers, their fears of a war against the western powers apparently proven groundless, and gratified by Germany's revenge against France for the defeat of 1918, reconciled themselves to Hitler's regime, choosing to ignore its darker side. The task of leading the resistance groups for a time fell to civilians, although a hard core of military plotters remained active.

Carl Goerdeler, the former lord mayor of Leipzig, emerged as a key figure. His associates included the diplomat Ulrich von Hassell, the Prussian Finance Minister Johannes Popitz, and Helmuth James Graf von Moltke, heir to a famous name and the leading figure in the Kreisau Circle of Prussian oppositionists, which included other young aristocrats such as Adam von Trott zu Solz and Peter Yorck von Wartenburg, and later Gottfried Graf von Bismarck-Schönhausen, who was a Nazi member of the Reichstag and a senior officer in the SS. Goerdeler was also in touch with the SPD underground, whose most prominent figure was Julius Leber, and with Christian opposition groups, both Catholic and Protestant.

These men saw themselves as the leaders of a post-Hitler government, but they had no clear conception of how to bring this about, except through assassinating Hitler – a step which many of them still opposed on ethical grounds. Their plans could never surmount the fundamental problem of Hitler's overwhelming popularity among the German people. They preoccupied themselves with philosophical debates and devising grand schemes for postwar Germany. The fact was that for nearly two years after the defeat of France, there was little scope for opposition activity.

Henning von Tresckow

In March 1941, Hitler revealed his plans for a "war of annihilation" against the Soviet Union to selected army officers in a speech given in Posen. In the audience was Colonel Henning von Tresckow, who had not been involved in any of the earlier plots but was already a firm opponent of the Nazi regime. He was horrified by Hitler's plan to unleash a new and even more terrible war in the east. As a nephew of Field Marshal Fedor von Bock, he was very well connected. Assigned to the staff of his uncle's command, Army Group Centre, for the forthcoming Operation Barbarossa, Tresckow systematically recruited oppositionists to the group's staff, making it the new nerve centre of the army resistance.

American journalist Howard K. Smith wrote in 1942 that of the three groups in opposition to Hitler, the military was more important than the churches and the Communists.[102] Little could be done while Hitler's armies advanced triumphantly into the western regions of the Soviet Union through 1941 and 1942 – even after the setback before Moscow in December 1941 that led to the dismissal of both Brauchitsch and Bock. In December 1941, the United States entered the war, persuading some more realistic army officers that Germany must ultimately lose the war. But the life-and-death struggle on the eastern front posed new problems for the resistance. Most of its members were conservatives who hated and feared communism and the Soviet Union. How could the Nazi regime be overthrown and the war ended without allowing the Soviets to gain control of Germany or the whole of Europe? This question was made more acute when the Allies adopted their policy of demanding Germany's "unconditional surrender" at the Casablanca Conference of January 1943.

During 1942, the tireless Oster nevertheless succeeded in rebuilding an effective resistance network. His most important recruit was General Friedrich Olbricht, head of the General Army Office headquartered at the Bendlerblock in central Berlin, who controlled an independent system of communications to reserve units all over Germany. Linking this asset to Tresckow's resistance group in Army Group Centre created what appeared to a viable structure for a new effort at organising a coup. Bock's dismissal did not weaken Tresckow's position. In fact he soon enticed Bock's successor, General Hans von Kluge, at least part-way to supporting the resistance cause. Tresckow even brought Goerdeler, leader of the civilian resistance, to Army Group Centre to meet Kluge – an extremely dangerous tactic.

Communist resistance

Memorial to Harro Schulze-Boysen, Niederkirchnerstrasse, Berlin

The entry of the Soviet Union into the war had certain consequences for the civilian resistance. During the period of the Nazi–Soviet Pact, the KPD's only objective inside Germany was to keep itself in existence: it engaged in no active resistance to the Nazi regime. After June 1941, however, all Communists were expected to throw themselves into resistance work, including sabotage and espionage where this was possible, regardless of risk. A handful of Soviet agents, mostly exiled German Communists, were able to enter Germany to help the scattered underground KPD cells organise and take action. This led to the formation in 1942 of two separate communist groups, usually erroneously lumped together under the name Rote Kapelle ("Red Orchestra"), a codename given to these groups by the Gestapo.

The first "Red Orchestra" was an espionage network based in Berlin and coordinated by Leopold Trepper, a GRU agent sent into Germany in October 1941. This group made reports to the Soviet Union on German troop concentrations, air attacks on Germany, German aircraft production, and German fuel shipments. In France, it worked with the underground French Communist Party. Agents of this group even managed to tap the phone lines of the Abwehr in Paris. Trepper was eventually arrested and the group broken up by the spring of 1943.

The second and more important "Red Orchestra" group was entirely separate and was a genuine German resistance group, not controlled by the NKVD (the Soviet intelligence agency and predecessor to the KGB). This group was led by Harro Schulze-Boysen, an intelligence officer at the Reich Air Ministry, and Arvid Harnack, an official in the Ministry of Economics, both self-identified communists but not apparently KPD members. The group however contained people of various beliefs and affiliations. It included the theatre producer Adam Kuckhoff, the author Günther Weisenborn, the journalist John Graudenz and the pianist Helmut Roloff. It thus conformed to the general pattern of German resistance groups of being drawn mainly from elite groups.

The main activity of the group was collecting information about Nazi atrocities and distributing leaflets against Hitler rather than espionage. They passed what they had learned to foreign countries, through personal contacts with the U.S. embassy and, via a less direct connection, to the Soviet government. When Soviet agents tried to enlist this group in their service, Schulze-Boysen and Harnack refused, since they wanted to maintain their political independence. The group was betrayed to the Gestapo in August 1942 by Johann Wenzel, a member of the Trepper group who also knew of the Schulze-Boysen group and who informed on them after being arrested. Schulze-Boysen, Harnack and other members of the group were arrested and secretly executed.

Meanwhile, another Communist resistance group was operating in Berlin, led by a Jewish electrician, Herbert Baum, and involving up to a hundred people. Until 1941, the group operated a study circle, but after the German attack on the Soviet Union a core group advanced to active resistance. In May 1942, the group staged an arson attack on an anti-Soviet propaganda display at the Lustgarten in central Berlin. The attack was poorly organised and most of the Baum group was arrested. Twenty were sentenced to death, while Baum himself "died in custody". This fiasco ended overt Communist resistance activities, although the KPD underground continued to operate, and re-emerged from hiding in the last days of the war.

Aeroplane assassination attempt

In late 1942, von Tresckow and Olbricht formulated a plan to assassinate Hitler and stage a coup. On 13 March 1943, returning from his easternmost headquarters FHQ Wehrwolf near Vinnitsa to Wolfsschanze in East Prussia, Hitler was scheduled to make a stop-over at the headquarters of Army Group Centre at Smolensk. For such an occasion, von Tresckow had prepared three options:[103]

- Major Georg von Boeselager, in command of a cavalry honor guard, could intercept Hitler in a forest and overwhelm the SS bodyguard and the Führer in a fair fight; this course was rejected because of the prospect of a large number of German soldiers fighting each other, and a possible failure regarding the unexpected strength of the escort.

- A joint assassination could be carried out during dinner; this idea was abandoned as supporting officers abhorred the idea of shooting the unarmed tyrant.

- A bomb could be smuggled on Hitler's plane.

Von Tresckow asked Lieutenant Colonel Heinz Brandt, on Hitler's staff and usually on the same plane that carried Hitler, to take a parcel with him, supposedly the prize of a bet won by Tresckow's friend General Stieff. It concealed a bomb, disguised in a box for two bottles of Cointreau. Von Tresckow's aide, Lieutenant Fabian von Schlabrendorff, set the fuse and handed over the parcel to Brandt who boarded the same plane as Hitler.[104]

Hitler's Focke-Wulf Fw 200 Condor was expected to explode about 30 minutes later near Minsk, close enough to the front to be attributed to Soviet fighters. Olbricht was to use the resulting crisis to mobilise his Reserve Army network to seize power in Berlin, Vienna, Munich and in the German Wehrkreis centres. It was an ambitious but credible plan, and might have worked if Hitler had indeed been killed, although persuading Army units to fight and overcome what could certainly have been fierce resistance from the SS could have been a major obstacle.

However, as with Elser's bomb in 1939 and all other attempts, luck favoured Hitler again, which was attributed to "Vorsehung" (providence). The British-made chemical pencil detonator on the bomb had been tested many times and was considered reliable. It went off, but the bomb did not. The percussion cap apparently became too cold as the parcel was carried in the unheated cargo hold.

Displaying great sangfroid, Schlabrendorff took the next plane to retrieve the package from Colonel Brandt before the content was discovered. The blocks of plastic explosives were later used by Gersdorff and Stauffenberg.

Suicide bombing attempts

Rudolf Christoph Freiherr von Gersdorff

A second attempt was made a few days later on 21 March 1943, when Hitler visited an exhibition of captured Soviet weaponry in Berlin's Zeughaus. One of Tresckow's friends, Colonel Rudolf Christoph Freiherr von Gersdorff, was scheduled to explain some exhibits, and volunteered to carry out a suicide bombing using the same bomb that had failed to go off on the plane, concealed on his person. However, the only new chemical fuse he could obtain was a ten-minute one. Hitler again left prematurely after hurrying through the exhibition much quicker than the scheduled 30 minutes. Gersdorff had to dash to a bathroom to defuse the bomb to save his life, and more importantly, prevent any suspicion.[105] This second failure temporarily demoralised the plotters at Army Group Centre. Gersdorff reported about the attempt after the war; the footage is often seen on German TV documentaries ("Die Nacht des Widerstands" etc.), including a photo showing Gersdorff and Hitler.

Axel von dem Bussche, member of the elite Infantry Regiment 9, volunteered to kill Hitler with hand grenades in November 1943 during a presentation of new winter uniforms, but the train containing them was destroyed by Allied bombs in Berlin, and the event had to be postponed. A second presentation scheduled for December at the Wolfsschanze was canceled on short notice as Hitler decided to travel to Berchtesgaden.

In January 1944, Bussche volunteered for another assassination attempt, but then he lost a leg in Russia. On February 11, another young officer, Ewald-Heinrich von Kleist tried to assassinate Hitler in the same way von dem Bussche had planned. However Hitler again canceled the event which would have allowed Kleist to approach him.

On 11 March 1944, Eberhard von Breitenbuch volunteered for an assassination attempt at the Berghof using a 7.65 mm Browning pistol concealed in his trouser pocket. He was not able to carry out the plan because guards would not allow him into the conference room with the Führer.

The next occasion was a weapons exhibition on July 7 at Schloss Klessheim near Salzburg, but Helmuth Stieff did not trigger the bomb.

After Stalingrad

Red Army soldier marches a German soldier into captivity after the victory at Battle of Stalingrad

At the end of 1942, Germany suffered a series of military defeats, the first at El Alamein, the second with the successful Allied landings in North Africa (Operation Torch), and the third the disastrous defeat at Stalingrad, which ended any hope of defeating the Soviet Union. Most experienced senior officers now came to the conclusion that Hitler was leading Germany to defeat, and that the result of this would be the Soviet conquest of Germany – the worst fate imaginable. This gave the military resistance new impetus.

Halder had been dismissed in 1942 and there was now no independent central leadership of the Army. His nominal successors, Field Marshal Wilhelm Keitel and General Alfred Jodl, were no more than Hitler's messengers. Tresckow and Goerdeler tried again to recruit the senior Army field commanders to support a seizure of power. Kluge was by now won over completely. Gersdorff was sent to see Field Marshal Erich von Manstein, the commander of Army Group South in the Ukraine. Manstein agreed that Hitler was leading Germany to defeat, but told Gersdorff that “Prussian field marshals do not mutiny.”[106] Field Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt, commander in the west, gave a similar answer. The prospect of a united German Army seizing power from Hitler was as far away as ever. Once again, however, neither officer reported that they had been approached in this way.

Nevertheless, the days when the military and civilian plotters could expect to escape detection were ending. After Stalingrad, Himmler would have had to be naïve not to expect that conspiracies against the regime would be hatched in the Army and elsewhere. He already suspected Canaris and his subordinates at the Abwehr. In March 1943, two of them, Oster and Hans von Dohnányi, were dismissed on suspicion of opposition activity, although there was yet insufficient evidence to have them arrested. On the civilian front, Dietrich Bonhoeffer was also arrested at this time, and Goerdeler was under suspicion.

The Gestapo had been led to Dohnanyi following the arrest of Wilhelm Schmidhuber, who had helped Dohnanyi with information and with smuggling Jews out of Germany. Under interrogation, Schmidhuber gave the Gestapo details of the Oster-Dohnanyi group in the Abwehr and about Goerdeler and Beck's involvement in opposition activities. The Gestapo reported all this to Himmler, with the observation that Canaris must be protecting Oster and Dohnanyi and the recommendation that he be arrested. Himmler passed the file back with the note "Kindly leave Canaris alone."[107] Either Himmler felt Canaris was too powerful to tackle at this stage, or he wanted him and his oppositional network protected for reasons of his own. Nevertheless, Oster's usefulness to the resistance was now greatly reduced. However, the Gestapo did not have information about the full workings of the resistance. Most importantly, they did not know about the resistance networks based on Army Group Centre or the Bendlerblock.

Meanwhile, the disaster at Stalingrad, which cost Germany 400,000 casualties, was sending waves of horror and grief through German society, but causing remarkably little reduction in the people's faith in Hitler and in Germany's ultimate victory. This was a source of great frustration to the military and civil service plotters, who virtually all came from the elite and had privileged access to information, giving them a much greater appreciation of the hopelessness of Germany's situation than was possessed by the German people.

The White Rose

The only visible manifestation of opposition to the regime following Stalingrad was the spontaneous action of few university students who denounced the war and the persecution and mass murder of Jews in the east. They were organised in the White Rose group, which was centered in Munich but had connections in Berlin, Hamburg, Stuttgart and Vienna.

In January 1943, they launched an anti-Nazi campaign of handbills and graffiti in and around Ludwig Maximilians University in Munich. They were detected and some arrested.

Three members, Hans Scholl, Sophie Scholl, and Christoph Probst were to stand trial before the Nazi "People's Court", where on 22 February 1943, the President of the court, Roland Freisler, sentenced them to death. They were guillotined that same day at Stadelheim Prison.

Kurt Huber, a professor of philosophy and musicology, Alexander Schmorell, and Willi Graf had to stand trial later and were sentenced to death as well, whereas many others were sentenced to prison terms. The last member to be executed was Hans Conrad Leipelt on 29 January 1945.

This outbreak was surprising and worrying to the Nazi regime, because the universities had been strongholds of Nazi sentiment even before Hitler had come to power. Similarly, it gave heart to the scattered and demoralised resistance groups. But White Rose was not a sign of widespread civilian disaffection from the regime, and had no imitators elsewhere, although their sixth leaflet, re-titled "The Manifesto of the Students of Munich", was dropped by Allied planes in July 1943, and became widely known in World War II Germany. The underground SPD and KPD were able to maintain their networks, and reported increasing discontent at the course of the war and at the resultant economic hardship, particularly among the industrial workers and among farmers (who suffered from the acute shortage of labour with so many young men away at the front). However, there was nothing approaching active hostility to the regime. Most Germans continued to revere Hitler and blamed Himmler or other subordinates for their troubles. From late 1943, fear of the advancing Soviets and prospects of a military offensive from the Western Powers eclipsed resentment at the regime and if anything hardened the will to resist the advancing allies.

Open Protest

Across the twentieth century public protest comprised a primary form of civilian opposition within totalitarian regimes. Potentially influential popular protests required not only public expression but the collection of a crowd of persons speaking with one voice. In addition, only protests which caused the regime to take notice and respond to are included here.

Improvised protests also occurred if rarely in Nazi Germany, and represent a form of resistance not wholly researched, Sybil Milton wrote already in 1984.[108]Hitler and National Socialism’s perceived dependence on the mass mobilization of his people, the “racial” Germans, along with the belief that Germany had lost WW I due to an unstable home front, caused the regime to be peculiarly sensitive to public, collective protests. Hitler recognized the power of collective action, advocated non-compliance toward unworthy authority (e.g. the 1923 French occupation of the Ruhr), and brought his party to power in part by mobilizing public unrest and disorder to further discredit the Weimar Republic.[109] In power, Nazi leadersquickly banned extra-party demonstrations, fearing displays of dissent on open urban spaces might develop and grow, even without organization.

To direct attention away from dissent, the Nazi state appeased some public, collective protests by “racial” Germans and ignored but did not repress others, both before and during the war. The regime rationalized appeasement of public protests as temporary measures to maintain the appearance of German unity and reduce the risk of alienating the public through blatant Gestapo repression. Examples of compromises for tactical reasons include social and material concessions to workers, deferment of punishing oppositional church leaders, “temporary” exemptions of intermarried Jews from the Holocaust, failure to punish hundreds of thousands of women for disregarding Hitler's ‘total war’ decree conscripting women into the work force, and rejection of coercion to enforce civilian evacuations from urban areas bombed by the Allies.

An early defeat of state institutions and Nazi officials by mass, popular protest culminated with Hitler's release and reinstatement to church office of Protestant bishops Hans Meiser and Theophil Wurm in October 1934.[110] Meiser's arrest two weeks earlier had stirred mass public protests of thousands in Bavaria and Württemberg and initiated protests to the German Foreign Ministry from countries around the world. Unrest had festered between regional Protestants and the state since early 1934 and came to a boil in mid-September when the regional party daily accused Meiser of treason, and shameful betrayal of Hitler and the state. By the time Hitler intervened, pastors were increasingly involving parishioners in the church struggle. Their agitation was amplifying distrust of the state as protest was worsening and spreading rapidly. Alarm among local officials was escalating. Some six thousand gathered in support of Meiser while only a few dutifully showed up at a meeting of the region's party leader, Julius Streicher. Mass open protests, the form of agitation and bandwagon building the Nazis employed so successfully, were now working against them. When Streicher's deputy, Karl Holz, held a mass rally in Nuremberg's main square, Adolf-Hitler-Platz, the director of the city's Protestant Seminary led his students into the square, encouraging others along the way to join, where they effectively sabotaged the Nazi rally and broke out singing “A Mighty Fortress is our God.” To rehabilitate Meiser and bring the standoff to a close, Hitler, who in January had publicly condemned the bishops in their presence as “traitors to the people, enemies of the Fatherland, and the destroyers of Germany,” arranged a mass audience including the bishops and spoke in conciliatory tones.[111]

This early contest points to enduring characteristics of regime responses to open, collective protests. It would prefer dealing with mass dissent immediately and decisively—not uncommonly retracting the cause of protest with local and policy-specific concessions. Open dissent, left unchecked, tended to spread and worsen. Church leaders had improvised a counter-demonstration strong enough to neutralize the party's rally just as the Nazi Party had faced down socialist and communist demonstrators while coming to power.[110] Instructive in this case is the view of a high state official that, regardless of the protesters motives, they were political in effect; although church protests were in defense of traditions rather than an attack on the regime, they nonetheless had political consequences, the official said, with many perceiving the clergy as anti-Nazi, and a “great danger of the issue spilling over from a church affair into the political arena”.[111]

Hitler recognized that workers, through repeated strikes, might force approval of their demands and he made concessions to workers in order to preempt unrest; yet the rare but forceful public protests the regime faced were by women and Catholics, primarily. Some of the earliest work on resistance examined the Catholic record, including most spectacularly local and regional protests against decrees removing crucifixes from schools, part of the regime's effort to secularize public life.[112] Although historians dispute the degree of political antagonism toward National Socialism behind these protests, their impact is uncontested. Popular, public, improvised protests against decrees replacing crucifixes with the Führer's picture, in incidents from 1935 to 1941, from north to south and east to west in Germany, forced state and party leaders to back away and leave crucifixes in traditional places. Prominent incidents of crucifix removal decrees, followed by protests and official retreat, occurred in Oldenburg (Lower Saxony) in 1936, Frankenholz (Saarland) and Frauenberg (East Prussia) in 1937, and in Bavaria in 1941. Women, with traditional sway over children and their spiritual welfare, played a leading part.[113]