Hathigumpha inscription

Hathigumpha on Udayagiri Hills, Bhubaneswar

The Hathigumpha inscription of Kharavela

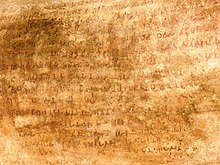

Hathigumpha inscription. From the Archaeological Survey of India Collections, taken by William Henry Cornish in c.1892.

Hathigumpha inscription of King Khāravela at Udayagiri Hills

Hathigumpha inscription of King Khāravela at Udayagiri Hills as first drawn in "Corpus Inscriptionum Indicarum, Volume I: Inscriptions of Asoka by Alexander Cunningham", 1827

The Hathigumpha Inscription ("Elephant Cave" inscription), from Udayagiri, near Bhubaneswar in Odisha, was inscribed by Kharavela, the then Emperor of Kalinga in India, during 2nd century BCE.[1] The Hathigumpha Inscription consists of seventeen lines in a Central-Western form of Prakrit incised in a deep-cut Brahmi script on the overhanging brow of a natural cavern called Hathigumpha in the southern side of the Udayagiri hill, near Bhubaneswar in Odisha. It faces straight towards the Rock Edicts of Ashoka at Dhauli, situated at a distance of about six miles.

The inscription is written in a type which is considered as one of the most archaic forms of the Kalinga alphabet, also suggesting a date around 150 BCE.[2]

The inscription is dated 13th year of Kharavela's reign, which has been dated variously by scholars from the 2nd century BCE[3] to the 1st century CE.[4][5][4]

Contents

1 Background

2 Salient features

3 See also

4 References

4.1 Citations

4.2 Sources

5 External links

Background

The Hathigumpha Inscription is the main source of information about Kalinga ruler Kharavela. This inscription, consisting of seventeen lines has been incised in deep cut Brahmi script of the 1st century BCE, on the overhanging brow of a natural cavern called Hathigumpha, in the southern side of the Udayagiri hill. It faces straight towards the Rock Edicts of Ashoka at Dhauli situated at a distance of about six miles. It was introduced to the Western world by A. Stirling in 1820, who published an eye copy of it in Asiatic Researches, XV, as well as in his book An Account, Geographical, Statistical and Historical of Orissa or Cuttack and by James Prinsep, who deciphered the inscription. Prinsep's reading along with the facsimile prepared by Kittoe was Published in the Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal, VI (1837), where he erroneously attributed this inscription to a king named Aira. Towards the end of 1871, a plaster-cast of the inscription was prepared by H. Locke, which is now preserved in the Indian Museum, Calcutta. Alexander Cunningham published this inscription in 1877 in the Corpus Inscriptionum Indicarum Vol. I, and in 1880 R.L. Mitra published a slightly modified version in his Antiquities of Orissa, Vol. II.

Bhagwan Lal Indraji is credited with the first authentic reading, which he presented before the Sixth International Congress of Orientalists, 1885. It is to be noted here that, Pandit Indraji was the first scholar to declare that the king eulogised in the Hathigumpha inscription was named Kharavela.[6] It is a fact that there is a large number of lacuna in the inscription, which obstruct its correct reading and because of its mutilated condition has given rise to unnecessary controversies.

The inscription mainly mentions the various conquests of this king, starting with his fight against the Satavahana king Satakarni:

- "And in the second year (he), disregarding Satakamini, dispatches to the western regions an army strong in cavalry, elephants, infantry (nara) and chariots (ratha) and by that army having reached the Kanha-bemna, he throws the city of the Musikas into consternation." Epigraphia Indica, Vol. XX

Salient features

The Hathigumpha inscription starts with a version of the auspicious Jain Namokar Mantra: नमो अरहंतानं [॥] णमो सवसिधानं [॥] for in Jainism.

The Hathigumpha Inscription mentions that:[7]

Possible statue of a Yavana/ Indo-Greek warrior with boots and chiton, from the Rani Gumpha or "Cave of the Queen" in the Udayagiri Caves on the east coast of India, where the Hathigumpha inscription was also found. 2nd or 1st century BCE.[8]

- In the very first year of his coronation (His Majesty) caused to be repaired the gate, rampart and structures of the fort of Kalinga Nagari, which had been damaged by storm, and caused to be built flight of steps for the cool tanks and laid all gardens at the cost of thirty five hundred thousand (coins) and thus pleased all his subjects.

- In the second year, without caring for Satakarni (His Majesty) sent to the west a large army consisting of horse, elephant, infantry and chariot, and struck terror to Asikanagara with that troop that marched up to the river Kanhavemna.

- Then in the fourth year, (His Majesty) .... the Vidhadhara tract, that had been established by the former kings of Kalinga and had never been crossed before. The Rathika and Bhojaka chiefs with their crown cast off, their umbrella and royal insignia thrown aside, and their Jewelry and wealth confiscated, were, made to pay obeisance at the feet (of His Majesty).

- And in the fifth year, (His Majesty) caused the aqueducts that had been excavated by king Nanda three hundred years before, to flow into [Kalinga] Nagri through Tanasuli.

- And in the seventh year of his reign (the Queen) of Vajiraghara, blessed with a son attained motherhood.

- In the 8th year of his reign, he attacked Rajagriha in Magadha and forced a Yavana king to retreat to Mathura:

.mw-parser-output .templatequote{overflow:hidden;margin:1em 0;padding:0 40px}.mw-parser-output .templatequote .templatequotecite{line-height:1.5em;text-align:left;padding-left:1.6em;margin-top:0}

"Then in the eighth year, (Kharavela) with a large army having sacked Goradhagiri causes pressure on Rajagaha (Rajagriha). On account of the loud report of this act of valour, the Yavana (Greek) King Dimi[ta] retreated to Mathura having extricated his demoralized army."

— Hathigumpha inscription, lines 7-8, probably in the 1st century BCE. Original text is in Brahmi script.[9]

- The name of the Yavana king is not clear, but it contains three letters, and the middle letter can be read as ma or mi.[10]R. D. Banerji and K.P. Jayaswal read the name of the Yavana king as "Dimita", and identify him with Demetrius I of Bactria. However, according to Ramaprasad Chanda, this identification results in "chronological impossibilities".[4] According to Sailendra Nath Sen, the Yavana ruler was certainly not Demerius; he might have been a later Indo-Greek ruler of eastern Punjab.[11] Numismatist P.L. Gupta interprets the name as "Vimaka", and identifies him with Vima Kadphises.[10] However, Vima Kadphises was a Kushana, not Yavana, king. It is otherwise unknown for a Kushan emperor to have been referred to as a Yavana, and for Vima Kadphises to be referred to as "Vimaka". Also, there are palaeographic problems with dating the Hathigumpha inscription to Vima Kadphises' period.

- In the 12th year of his reign, he attacked the king of Uttarapatha. Then brought back the holy idols of Kalinga's Jain Gods (The Blessed Tirthankars) which earlier Magadha rulers had carried away with them after Kalinga War in Past. Tirthankar’s idol was brought back with its crown and endowment and the jewels plundered by king Nanda from the Kalinga royal palace, along with the treasures of Anga and Magadha were regained.

- He then attacks the kingdom of Magadha, and in Pataliputra, the capital of the Shunga Empire, makes king "Bahasatimita" (thought to be the Shunga King Brhaspatimitra, or Pushyamitra himself) bow at his feet.

See also

- Indian inscriptions

References

Citations

^ Krishan 1996, p. 23.

^ Source

^ Alain Daniélou (11 February 2003). A Brief History of India. Inner Traditions / Bear & Co. pp. 139–141. ISBN 978-1-59477-794-3..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ abc Sudhakar Chattopadhyaya (1974). Some Early Dynasties of South India. Motilal Banarsidass Publ. pp. 44–50. ISBN 978-81-208-2941-1.

^ Rama Shankar Tripathi (1942). History of Ancient India. Motilal Banarsidass Publ. pp. 199–201. ISBN 978-81-208-0018-2.

^ A. F. Rudolf Hoernlé (2 February 1898). "Full text of "Annual address delivered to the Asiatic Society of Bengal, Calcutta, 2nd February, 1898"". Asiatic Society of Bengal. Retrieved 4 September 2014.

^ Full text of the Hathigumpha Inscription in English Archived 3 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine

^ "The taut posture and location at the entrance of the cave (Rani Gumpha) suggests that the male figure is a guard or dvarapala. The aggressive stance of the figure and its western dress (short kilt and boots) indicates that the sculpture may be that of a Yavana, foreigner from the Graeco-Roman world." in Early Sculptural Art in the Indian Coastlands: A Study in Cultural Transmission and Syncretism (300 BCE-CE 500), by Sunil Gupta, D K Printworld (P) Limited, 2008, p.85

^ Translation in Epigraphia Indica 1920 p.87

^ ab Kusâna Coins and History, D.K. Printworld, 1994, p.184, note 5; reprint of a 1985 article

^ Sailendra Nath Sen (1999). Ancient Indian History and Civilization. New Age International. pp. 176–177. ISBN 978-81-224-1198-0.

Sources

- Epigraphia Indica, Vol. XX (1929–30). Delhi: Manager of Publications, 1933.

- Sadananda Agrawal: Śrī Khāravela, Published by Sri Digambar Jain Samaj, Cuttack, 2000.

Krishan, Yuvraj (1996), The Buddha Image: Its Origin and Development, Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan, ISBN 9788121505659

Singh, Upinder (2016), A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India: From the Stone Age to the 12th Century, Pearson PLC, ISBN 978-81-317-1677-9

External links

- Epigraphia Indica, Vol. XX (1929–30). Delhi: Manager of Publications, Reprinted 1983.

- Full text of the Hathigumpha inscription in English

- Comparative study of the Inscriptions of Kharavela and Vasishithiputra Pulumavi

- Palaeography, language and art of Hatigumpha inscription