Ushavadata

Karla caves Chaitya pillars (left) compared to Pandavleni Caves Cave No10 pillars (right), all built by Ushavadata, son-in-law of Nahapana, circa 120 CE.

Ushavadata (IAST: Uṣavadāta), also known as Rishabhadatta, was a viceroy and son-in-law of the Western Kshatrapa ruler Nahapana, who ruled in western India.

Contents

1 Inscriptions

2 Early life

3 Charity

4 Military career

5 See also

6 References

6.1 Bibliography

Inscriptions

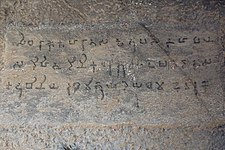

Nasik Cave inscription No.10. of Ushavadata, Cave No.10.

Much of the information about Ushavadata comes from his Nashik and Karle inscriptions. The Nashik inscription contains an eulogy of Ushavadata in Sanskrit, and then records the donation of a cave to Buddhists in a Middle Indo-Aryan language. The Karle inscription contains a similar eulogy, but in the Middle Indo-Aryan language.[1]

Early life

Ushavadata was the son of one Dinika.[2] He identifies as a Shaka (IAST: Śaka) in his Nashik inscription:

.mw-parser-output .templatequote{overflow:hidden;margin:1em 0;padding:0 40px}.mw-parser-output .templatequote .templatequotecite{line-height:1.5em;text-align:left;padding-left:1.6em;margin-top:0}

"[Success !] By permanent charities of Ushavadata, the Shaka, [son of Dinika], son-in-law of king Nahapana, the [Kshahara]ta Kshatrapa...."

— Inscription No.14a of Nahapana, Cave No.10, Nasik[3]

He believed in Brahmanism,[4] and married Nahapana's daughter Dakshamitra.

Charity

Both of Ushavadata's inscriptions mention the following of his charitable acts:[2]

- Donated 300,000 cows

- Donated gold for the establishment of a holy site on the banks of the Barnasa river

- Donated 16 villages to the deities and Brahmanas (priests)

- Gave 8 wives to the Brahmanas at the holy site of Prabhasa

- Fed hundreds of thousands of Brahmanas every year

The Nashik inscription records more such acts, stating that Ushavadata exhibited very pious behaviour at the Trirashmi hills, on which hte Nashik caves are located:[5]

- Donated four-roomed rest houses in Bharukachchha (Bharuch), Dashapura (Mandsaur), Govardhana (near Nashik), and Shurparaka (Nala Sopara)

- Commissioned gardens, tanks, and wells

- Established free crossings at several rivers, including Iba, Parada, Damana, Tapi, Karabena, Dahanuka, and Nava

- Established public water stations on both the banks of these rivers

- Donated 32,000 coconut tree stems at Nanamgola village to the associations of charakas at Pimditakavada, Govardhana, Suvarnamukha, and Shurparaka

- Purchased a field from a Brahmana family, and donated it to Buddhists along with a rock-cut cave (one of the Nasik Caves).[1]

"Success! In the year 42, in the month Vesakha, Ushavadata, son of Dinika, son-in-law of king Nahapana, the Kshaharata Kshatrapa, has bestowed this cave on the Samgha generally...."

— Inscription No.12 of Nahapana, Cave No.10, Nasik[6]

Nasik Pandavleni Caves, cave No.10 | |

| |

Military career

Ushavadatta campaigned in the north under the orders of Nahapana to rescue the Uttamabhadras, who had been attacked by the Malayas (identified with the Malavas).[7]

The Satavahana king Gautamiputra Satakarni appears to have defeated Rishabhadatta. An inscription discovered in Nashik, dated to the 18th year of Gautamiputra's reign, states that he donated a piece of land to Buddhist monks; this land was earlier in the possession of Ushavadata.[8]

See also

- Nasik inscription of Ushavadata

References

^ ab Andrew Ollett 2017, p. 39.

^ ab Andrew Ollett 2017, p. 40.

^ Epigraphia Indica p.85-86

^ N. B. Divatia 1993, p. 42.

^ Andrew Ollett 2017, pp. 39-40.

^ Epigraphia Indica p.82-83

^ Inscription No.10 of Nahapana, Cave No.10, Nasik, in p.78-79 Epigraphia Indica

^ Upinder Singh 2008, p. 383.

Bibliography

.mw-parser-output .refbegin{font-size:90%;margin-bottom:0.5em}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ul{list-style-type:none;margin-left:0}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ul>li,.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>dl>dd{margin-left:0;padding-left:3.2em;text-indent:-3.2em;list-style:none}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-100{font-size:100%}

Andrew Ollett (2017). Language of the Snakes: Prakrit, Sanskrit, and the Language Order of Premodern India. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-29622-0..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

N. B. Divatia (1993). Gujarati Language and Literature. Asian Educational Services. ISBN 81-206-0648-5.

Upinder Singh (2008). A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India: From the Stone Age to the 12th Century. Pearson Education India. ISBN 978-81-317-1120-0.