Mexican War of Independence

This article may be expanded with text translated from the corresponding article in Spanish. (August 2012) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

| Mexican War of Independence | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Spanish American wars of independence | |||||||||

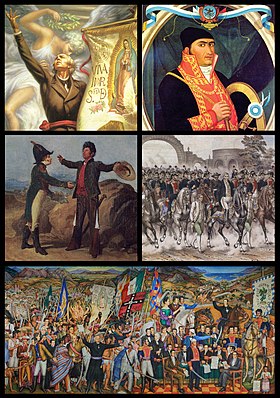

Clockwise from top left: Miguel Hidalgo, José María Morelos, Embrace of Acatempan between Iturbide and Guerrero, Trigarante Army in Mexico City, Mural of independence by O'Gorman | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

Mina (1817) | |||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

250,000–500,000 killed[1] | |||||||||

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Mexico |

|

Pre-Columbian |

Spanish rule

|

First Republic ġ

|

Second Federal Republic

|

1864–1928

|

Modern

|

Timeline |

The Mexican War of Independence (Spanish: Guerra de Independencia de México) was an armed conflict, and the culmination of a political and social process which ended the rule of Spain in 1821 in the territory of New Spain. The war had its antecedent in Napoleon's French invasion of Spain in 1808; it extended from the Cry of Dolores by Father Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla on September 16, 1810, to the entrance of the Army of the Three Guarantees led by Agustín de Iturbide to Mexico City on September 27, 1821. September 16 is celebrated as Mexican Independence Day.

The movement for independence was inspired by the Age of Enlightenment[2] and the American and French Revolutions. By that time the educated elite of New Spain had begun to reflect on the relations between Spain and its colonial kingdoms. Changes in the social and political structure occasioned by Bourbon Reforms and a deep economic crisis in New Spain caused discomfort among the native-born Creole elite.

The dramatic political events in Europe, the French Revolutionary Wars and the conquests of Napoleon deeply influenced events in New Spain. In 1808, Charles IV and Ferdinand VII were forced to abdicate in favor of the French Emperor, who then made his elder brother Joseph king. The same year, the ayuntamiento (city council) of Mexico City, supported by viceroy José de Iturrigaray, claimed sovereignty in the absence of the legitimate king. That led to a coup against the viceroy; when it was suppressed, the leaders of the movement were jailed.

Despite the defeat in Mexico City, small groups of rebels met in other cities of New Spain to raise movements against colonial rule. In 1810, after being discovered, Querétaro conspirators chose to take up arms on September 16 in the company of peasants and indigenous inhabitants of Dolores (Guanajuato), who were called to action by the secular Catholic priest Miguel Hidalgo, former rector of the Colegio de San Nicolás Obispo.

After 1810 the independence movement went through several stages, as leaders were imprisoned or executed by forces loyal to Spain. At first the rebels disputed the legitimacy of the French-installed Joseph Bonaparte while recognizing the sovereignty of Ferdinand VII over Spain and its colonies, but later the leaders took more radical positions, rejecting the Spanish claim and espousing a new social order including the abolition of slavery. Secular priest José María Morelos called the separatist provinces to form the Congress of Chilpancingo, which gave the insurgency its own legal framework. After the defeat of Morelos, the movement survived as a guerrilla war under the leadership of Vicente Guerrero. By 1820, the few rebel groups survived most notably in the Sierra Madre del Sur and Veracruz.

The reinstatement of the liberal Constitution of Cadiz in 1820 caused a change of mind among the elite groups who had supported Spanish rule. Monarchist Creoles affected by the constitution decided to support the independence of New Spain; they sought an alliance with the former insurgent resistance. Agustín de Iturbide led the military arm of the conspirators and in early 1821 he met Vicente Guerrero. Both proclaimed the Plan of Iguala, which called for the union of all insurgent factions and was supported by both the aristocracy and clergy of New Spain. It called for a monarchy in an independent Mexico. Finally, the independence of Mexico was achieved on September 27, 1821.[3]

After that, the mainland of New Spain was organized as the Mexican Empire.[4] This ephemeral Catholic monarchy changed to a federal republic in 1823, due to internal conflicts and the separation of Central America from Mexico.

After some Spanish reconquest attempts, including the expedition of Isidro Barradas in 1829, Spain under the rule of Isabella II recognized the independence of Mexico in 1836.[5]

Contents

1 Background

2 Course of the war

2.1 First phase of the insurgency: the Hidalgo revolt (1810–1815)

2.2 Second phase of the insurgency and independence (1815–1821)

3 Treaty of Córdoba

4 Aftermath

4.1 Creation of the First Mexican Empire

4.2 Spanish attempts to reconquer Mexico

5 Construction of Historical Memory of Independence

6 See also

7 References

8 Further reading

9 External links

Background

Mexican resistance and struggle for independence began with the brutal Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire when Spanish conquerors had considerable autonomy from crown control. Don Martín Cortés (son of Hernán Cortés), the second marquis of the Valley of Oaxaca, led a conspiracy of holders of encomiendas against the Spanish crown after it sought to eliminate privileges for the conquistadors, particularly putting limitations on encomiendas.[6] After the suppression of that mid-16th-century conspiracy, elites raised no substantial challenge to royal rule until the Hidalgo revolt of 1810.

Elites in Mexico City in the seventeenth century did force the removal of a reformist viceroy, the Marqués de Gelves, following an urban riot in 1624 fomented by those elites. He attempted to eliminate corrupt practices by creole elites as well as rein in the opulent displays of the clergy's power, but ecclesiastical authorities in conjunction with creole elites mobilized urban plebeians to oust the viceroy.[7][8] The crowd was reported to shout, "Long live the King! Love live Christ! Death to bad government! Death to the heretic Lutheran [Viceroy Gelves]! Arrest the viceroy!" The attack was against Gelves as a bad representative of the crown and not against the monarchy or colonial rule itself.[9]

There was also a brief conspiracy in the mid-seventeenth century to unite creole elites, blacks, and indigenous against the Spanish crown and proclaim Mexican independence. The man pushing this notion called himself Don Guillén Lampart y Guzmán, an Irishman born William Lamport. Lamport's conspiracy was discovered, and he was arrested by the Inquisition in 1642, and executed fifteen years later for sedition. There is a statue of Lamport in the mausoleum at the base of the Angel of Independence in Mexico City.

At the end of the seventeenth century, there was a major riot in Mexico City where a mob attempted to burn down the viceroy's palace and the archbishop's residence. A painting[10] by Cristóbal Villalpando shows the damage of the 1692 tumulto. Unlike the earlier one in 1624 in which elites were involved, the viceroy ousted, and no repercussions against the instigators, the 1692 riot was by plebeians alone and racially charged. The rioters attacked key symbols of Spanish power and shouted political slogans. "Kill the [American-born] Spaniards and the Gachupines [Iberian-born Spaniards] who eat our corn! We go to war happily! God wants us to finish off the Spaniards! We do not care if we die without confession! Is this not our land?"[11] The viceroy attempted to address the apparent cause of the riot, higher maize prices that affected the urban poor. But the 1692 riot "represented class warfare that put Spanish authority at risk. Punishment was swift and brutal, and no further riots in the capital challenged the Pax Hispanica."[12]

The various indigenous rebellions in the colonial era were often to throw off crown rule, but they were not an independence movement as such. However, during the war of independence, issues at the local level in rural areas constituted what one historian has called "the other rebellion."[13]

American-born Spaniards in New Spain developed a special understanding and ties to their New World homeland, what has been seen the formation of Creole patriotism. They did not, however, pursue political independence from Spain until the Napoleonic invasion of the Iberian peninsula and defeat of Spain destabilized the monarchy.[14][15] With the implementation of the Bourbon Reforms starting in the mid-eighteenth century, the Spanish crown sought to impose restrictions on creole elites.

In the early 19th century, Napoleon's occupation of Spain led to an outbreak of numerous revolts against colonial government across Spanish America. After the abortive Conspiracy of the Machetes in 1799, a massive revolt in the Bajío region was led by secular cleric Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla.[16] His Grito de Dolores was the first stage of the insurgency for Mexican independence.[16][17] Before 1810, there was no significant support for independence. Once the Hidalgo revolt was underway, it received major support only in the Bajío and parts of Jalisco.[18]

Course of the war

First phase of the insurgency: the Hidalgo revolt (1810–1815)

Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla, a priest and member of a group of educated Criollos in Querétaro City, hosted secret gatherings in his home to discuss whether it was better to obey or to revolt against a tyrannical government, as he defined the Spanish colonial government in Mexico. Famed military leader Ignacio Allende was among the attendees. In 1810 Hidalgo concluded that a revolt was needed because of injustices against the poor of Mexico. By this time Hidalgo was known for his achievements at the prestigious San Nicolás Obispo school in Valladolid (now Morelia), and later service there as rector. He also became known as a top theologian. When his older brother died in 1803, Hidalgo took over as priest for the town of Dolores.[19]

Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla, by José Clemente Orozco, Jalisco Governmental Palace, Guadalajara

Hidalgo was in Dolores on 15 September 1810, with other rebel leaders including commander Allende, when they learned their conspiracy had been discovered. Hidalgo ran to the church, calling for all the people to gather, where from the pulpit he called upon them to revolt. They all shouted in agreement. The people were a comparatively small group, and poorly armed with whatever was at hand, including sticks and rocks. On the morning of 16 September 1810, Hidalgo called upon the remaining locals who happened to be in the market, and again, from the pulpit, exhorted the people of Dolores to join him. Most did: Hidalgo had a mob of some 600 men within minutes. This became known as the Grito de Dolores or Cry of Dolores.

Hidalgo and Allende marched their little army through towns including San Miguel and Celaya, where the angry rebels killed all the Spaniards they found. Along the way they adopted the standard of the Virgin of Guadalupe as their symbol and protector. When they reached the town of Guanajuato on September 28, they found Spanish forces barricaded inside the public granary, Alhóndiga de Granaditas. Among them were some 'forced' Royalists, creoles who had served and sided with the Spanish. By this time, the rebels numbered 30,000 and the battle was horrific. They killed more than 500 Spanish and creoles, and marched on toward Mexico City.

The Viceroy quickly organized a defense, sending out the Spanish general Torcuato Trujillo with 1,000 men, 400 horsemen, and 2 cannons - all that could be found on such short notice. Ignacio Lopez Rayon joined Hidalgo's forces whilst passing near Maravatío, Michoacan while en route to Mexico City and on October 30, Hidalgo's army encountered Spanish military resistance at the Battle of Monte de las Cruces, fought them, and achieved victory. When the cannons were captured by the rebels, the surviving Royalists retreated to the City.

Despite having the advantage, Hidalgo retreated, against the counsel of Allende. This retreat, on the verge of apparent victory, has puzzled historians and biographers ever since. They generally believe that Hidalgo wanted to spare the numerous Mexican citizens in Mexico City from the inevitable sacking and plunder that would have ensued. His retreat is considered Hidalgo's greatest tactical error.[19]

Father José María Morelos

Rebel survivors sought refuge in nearby provinces and villages. The insurgent forces planned a defensive strategy at a bridge on the Calderón River, pursued by the Spanish army. In January 1811, Spanish forces, led by Félix María Calleja del Rey fought the Battle of the Bridge of Calderón and defeated the insurgent army, forcing the rebels to flee north towards the United States, hoping they would attain financial and military support.[20]

But they were intercepted by Ignacio Elizondo, who pretended to join the fleeing insurgent forces. Hidalgo and his remaining soldiers were captured in the state of Coahuila at the Wells of Baján (Norias de Baján). All of the rebel leaders were found guilty of treason and sentenced to death, except for Mariano Abasolo. He was sent to Spain to serve a life sentence in prison. Allende, Jiménez and Aldama were executed on 26 June 1811, shot in the back as a sign of dishonor. Hidalgo, as a priest, had to undergo a civil trial and review by the Inquisition. He was eventually stripped of his priesthood, found guilty, and executed on 30 July. The heads of Hidalgo, Allende, Aldama and Jiménez were preserved and hung from the four corners of the Alhóndiga de Granaditas of Guanajuato as a warning to those who dared follow in their footsteps.

After Ignacio Lopez Rayon — stationed in Saltillo, Coahuila with 3,500 men and 22 cannons — heard of the capture of the insurgent leaders, he decided to flee back south on 26 March, 1811 to continue the fight. He subsequently fought the Spanish in the battles of Puerto de Piñones, Zacatecas, El Maguey, and Zitácuaro.

Following the execution of Hidalgo, José María Morelos took over leadership of the insurgency. In January 1812 he arrived at Cuautla, after which followed the 72-day Siege of Cuautla.[21] He achieved the occupation of the cities of Oaxaca and Acapulco. In 1813, he convened the Congress of Chilpancingo to bring representatives together and, on 6 November of that year, the Congress signed the first official document of independence, known as the Solemn Act of the Declaration of Independence of Northern America. In 1815, Morelos was captured by Spanish colonial authorities, tried and executed for treason.[22]

Second phase of the insurgency and independence (1815–1821)

From 1815 to 1821 most of the fighting for independence from Spain was done by small and isolated guerrilla bands. From these, two leaders arose: Guadalupe Victoria (born José Miguel Fernández y Félix) in Puebla and Vicente Guerrero in Oaxaca, both of whom gained allegiance and respect from their followers. Believing the situation under control, the Spanish viceroy issued a general pardon to every rebel who would lay down his arms. After ten years of civil war and the death of two of its founders, by early 1820 the independence movement was stalemated and close to collapse. The rebels faced stiff Spanish military resistance and the apathy of many of the most influential criollos.[23]

Oil painting of Agustín de Iturbide, leader of independence who was declared Emperor Augustín I, in 1822 following independence

In what was supposed to be the final government campaign against the insurgents, in December 1820, Viceroy Juan Ruiz de Apodaca sent a force led by a royalist criollo Colonel Agustín de Iturbide, to defeat Guerrero's army in Oaxaca. Iturbide, a native of Valladolid (now Morelia), had gained renown for his zeal against Hidalgo's and Morelos's rebels during the early independence struggle. A favorite of the Mexican church hierarchy, Iturbide symbolized conservative criollo values; he was devoutly religious, and committed to the defense of property rights and social privileges. He also resented his lack of promotion and failure to gain wealth.[24]

Portrait of Vicente Guerrero, mixed-race guerrilla leader of independence and later president of Mexico

Iturbide's assignment to the Oaxaca expedition coincided with a successful military coup in Spain against the monarchy of Ferdinand VII. The coup leaders, part of an expeditionary force assembled to suppress the independence movements in the Americas, had turned against the monarchy. They compelled the reluctant Ferdinand to reinstate the liberal Spanish Constitution of 1812 that created a constitutional monarchy. When news of the liberal charter reached Mexico, Iturbide perceived it both as a threat to the status quo and a catalyst to rouse the criollos to gain control of Mexico. Independence was achieved when conservative Royalist forces in the colonies chose to rise up against the liberal regime in Spain; it was an about-face compared to their previous opposition to the peasant insurgency. After an initial clash with Guerrero's forces, Iturbide assumed command of the royal army. At Iguala, he allied his formerly royalist force with Guerrero’s radical insurgents to discuss the renewed struggle for independence.

While stationed in the town of Iguala, Iturbide proclaimed three principles, or "guarantees," for Mexican independence from Spain. Mexico would be an independent monarchy governed by King Ferdinand, another Bourbon prince, or some other conservative European prince; criollos would be given equal rights and privileges to peninsulares; and the Roman Catholic Church in Mexico would retain its privileges and position as the established religion of the land. After convincing his troops to accept the principles, which were promulgated on February 24, 1821 as the Plan of Iguala, Iturbide persuaded Guerrero to join his forces in support of this conservative independence movement. A new army, the Army of the Three Guarantees, was placed under Iturbide's command to enforce the Plan of Iguala. The plan was so broadly based that it pleased both patriots and loyalists. The goal of independence and the protection of Roman Catholicism brought together all factions.[25]

Treaty of Córdoba

Iturbide's army was joined by rebel forces from all over Mexico. When the rebels' victory became certain, the Viceroy resigned. On August 24, 1821, representatives of the Spanish crown and Iturbide signed the Treaty of Córdoba, which recognized Mexican independence under the Plan of Iguala.[26]

Aftermath

Creation of the First Mexican Empire

On September 27, 1821 the Army of the Three Guarantees entered Mexico City, and the following day Iturbide proclaimed the independence of the Mexican Empire, as New Spain was henceforth to be called. The Treaty of Córdoba was not ratified by the Spanish Cortes. Iturbide included a special clause in the treaty that left open the possibility for a criollo monarch to be appointed by a Mexican congress if no suitable member of the European royalty would accept the Mexican crown. Half of the new government employees appointed were Iturbide's followers.[27]

On the night of the May 18, 1822, a mass demonstration led by the Regiment of Celaya, which Iturbide had commanded during the war, marched through the streets and demanded their commander-in-chief to accept the throne. The following day, the Congress declared Iturbide Emperor of Mexico. On October 31, 1822 Iturbide dissolved Congress and replaced it with a sympathetic junta.[28]

Spanish attempts to reconquer Mexico

Despite the creation of the Mexican nation, the Spanish still managed to hold onto a port in Veracruz that Mexico did not get control of until 23 November 1825.

On 28 December 1836, Spain recognized the independence of Mexico under the Santa María–Calatrava Treaty, signed in Madrid by the Mexican Commissioner Miguel Santa María and the Spanish state minister José María Calatrava.[29][30] Mexico was the first former colony whose independence was recognized by Spain; the second was Ecuador on 16 February 1840.

Construction of Historical Memory of Independence

Flag of the Army of the Three Guarantees

Flag of the Mexican Empire of Iturbide, the template for the modern Mexican flag with the eagle perched on a cactus. The crown on the eagle's head symbolizes monarchy in Mexico.

In 1910, as part of the celebrations marking the centennial of the Hidalgo revolt of 1810, President Porfirio Díaz inaugurated the monument to Mexico's political separation from Spain, the Angel of Independence on Avenida Reforma. The creation of this architectural monument is part of the long process of the construction of historical memory of Mexican independence.

Although Mexico gained its independence in September 1821, the marking of this historical event did not take hold immediately. The choice of date to celebrate was problematic, because Iturbide, who achieved independence from Spain, was rapidly created Emperor of Mexico. His short-lived reign from 1821–22 ended when he was forced by the military to abdicate. This was a rocky start for the new nation, which made celebrating independence on the anniversary of Iturbide's Army of the Three Guarantees marching into Mexico City in triumph a less than perfect day for those who had opposed him. Celebrations of independence during his reign were marked on September 27. Following his ouster, there were calls to commemorate Mexican independence along the lines that the United States celebrated in grand style its Independence Day on July 4. The creation of a committee of powerful men to mark independence celebrations, the Junta Patriótica, organized celebrations of both September 16, to commemorate Hidalgo's grito and the start of the independence insurgency, and September 27, to celebrate actual political independence.[31]

During the Díaz regime (1876–1911), the president's birthday coincided with the September 15/16 celebration of independence. The largest celebrations took place and continue to do so in the capital's main square, the zócalo, with the pealing of the Metropolitan Cathedral of Mexico City's bells. In the 1880s, government officials attempted to move the bell that Hidalgo rang in 1810 to gather parishioners in Dolores for what became his famous "grito". Initially the pueblo's officials said the bell no longer existed, but in 1896, the bell, known as the Bell of San José, was taken to the capital. It was renamed the "Bell of Independence" and ritually rung by Díaz. It is now an integral part of Independence Day festivities.[32]

See also

- Afro-Mexicans in the Mexican War of Independence

- List of wars involving Mexico

- Spanish attempts to reconquer Mexico

- Timeline of Mexican War of Independence

References

^ Scheina. Latin America's Wars. p. 84..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ https://www.inside-mexico.com/mexican-independence-facts/ accessed Jan 11, 2019

^ https://www.monografias.com/trabajos96/mexico-independiente-1821-1851/mexico-independiente-1821-1851.shtml#eltriunfoa accessed Dec 21, 2018.

^ https://www.monografias.com/trabajos96/mexico-independiente-1821-1851/mexico-independiente-1821-1851.shtml#eltriunfoa accessed Dec 21, 2018.

^ http://pares.mcu.es/Bicentenarios/portal/reconocimientoEspana.html accessed Dec 21, 2018.

^ John Charles Chasteen. Born in Blood and Fire: A Concise History of Latin America. New York, Norton, 2001.

ISBN 978-0-393-97613-7

^ Ida Altman, Sarah Cline, and Javier Pescador, The Early History of Greater Mexico. Prentice Hall 2003, pp. 246-247.

^ Jonathan I. Israel. Race, Class, and Politics in Colonial Mexico, 1610-1670. Oxford: Oxford University Press 1975.

^ Altman et al, The Early History of Greater Mexico, p. 247.

^ https://books.google.com.mx/books?id=McqRsf_KoX4C&pg=PA139&dq=1692+tumulto+cristobal+de+villalpando&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwiys4XFrrLfAhUIRa0KHQmpDlsQ6AEIOjAC#v=onepage&q=1692%20tumulto%20cristobal%20de%20villalpando&f=false accessed Dec 21, 2018

^ quoted in Altman et al, The Early History of Greater Mexico, p. 248.

^ Altman et al, The Early History of Greater Mexico, p. 249.

^ Eric Van Young, The Other Rebellion: Popular Violence, Ideology, and the Mexican Struggle for Independence, 1810-1821. Stanford: Stanfor University Press 2001.

^ D.A. Brading, The First America: the Spanish Monarchy, Creole Patriots, and the Liberal State, 1492-1867. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press 1991.

^ John Tutino, From Insurrection to Revolution in Mexico: Social Bases of Agrarian Violence, 1750-1940. Princeton: Princeton University Press 1986.

^ ab Hugh Hamill, The Hidalgo Revolt. Gainesville: University of Florida Press 1966, pp. 90-94.

^ John Tutino, From Insurrection to Revolution, pp. 126-138.

^ Tutino, From Insurrection to Revolution, pp. 138-183.

^ ab Robert Harvey (2000). Liberators: Latin America's Struggle For Independence. Woodstock: The Overlook Press. Archived from the original on 2013-07-10.

^ Philip Young. History of Mexico: Her Civil Wars and Colonial and Revolutionary Annals. Gardners Books, [1847] 2007, pp. 84-86.

ISBN 978-0-548-32604-6

^ http://www.lhistoria.com/mexico/sitio-de-cuautla accessed Dec 21, 2018.

^ Leslie Bethell (1987). The Independence of Latin America. Cambridge University Press. p. 65.

^ Timothy J. Henderson (2009). The Mexican Wars for Independence. pp. 115–16.

^ .Christon I. Archer, "Royalist Scourge or Liberator of the Patria? Agustín de Iturbide and Mexico's War of Independence, 1810-1821," Mexican Studies / Estudios Mexicanos (2008) 24#2 pp 325-361

^ Michael S. Werner (2001). Concise Encyclopedia of Mexico. Taylor & Francis. pp. 308–9.

^ Nettie Lee Benson (1992). The Provincial Deputation in Mexico: Harbinger of Provincial Autonomy, Independence, and Federalism. University of Texas Press. p. 42.

^ Philip Russell (2011). The History of Mexico: From Pre-Conquest to Present. Routledge. p. 132.

^ Christon I. Archer (2007). The Birth of Modern Mexico, 1780-1824. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 220.

^ Orozco Linares, Fernando (1996). Fechas históricas de México: las efemérides más destacadas desde la época prehispánica hasta nuestros días (in Spanish). Panorama Editorial. p. 128. ISBN 9789683802958. Retrieved 22 August 2018.

^ "Tratado Definitivo de Paz entre Mexico y España" (PDF) (in Spanish).

^ Michael Costeloe, "The Junta Patriótica and the Celebration of Independence in Mexico City, 1825-1855" in !Viva Mexico! !Viva la Independencia! Celebrations of September 16, eds. William H. Beezley and David E. Lorey. Wilmington: SR Books 2001, pp. 44-45.

^ Isabel Fernández Tejedo and Carmen Nava Nava, "Images of Independence in the Nineteenth Century: The 'Grito de Dolores', History and Myth" in !Viva Mexico! !Viva la Independencia! Celebrations of September 16, eds. William H. Beezley and David E. Lorey. Wilmington: SR Books 2001, pp. 33-34.

Further reading

Anna, Timothy E. (1978). The Fall of Royal Government in Mexico City. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0-8032-0957-6.

- Beezley, William H. and David E. Lorey, eds. !Viva Mexico! !Viva la Independencia!: Celebrations of September 16. Wilmington DL: Scholarly Resources Books 2001.

- Benjamin, Thomas. (2000). Revolución: Mexico's Great Revolution as Memory, Myth, and History (University of Texas Press).

ISBN 978-0-292-70880-8

Christon I. Archer, ed. (2003). The Birth of Modern Mexico. Willmington, Delaware: SR Books. ISBN 0-8420-5126-0.

- Dominguez, Jorge. Insurrection or Loyalty: the Breakdown of the Spanish American Empire. Cambridge: Harvard University Press 1980.

- García, Pedro. Con el cura Hidalgo en la guerra de independencia en México. Mexico City: Fondo de Cultura Económica 1982.

- Hamill, Jr. Hugh M. "Early Psychological Warfare in the Hidalgo Revolt," Hispanic American Historical Review (1961) 41#2 pp. 206–235 in JSTOR

Hamill, Hugh M. (1966). The Hidalgo Revolt: Prelude to Mexican Independence. Gainesville: University of Florida Press.

Hamnett, Brian R. (1986). Roots of Insurgency: Mexican Regions, 1750–1824. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521-3214-88.

- Hamnett, Brian. "Royalist Counterinsurgency and the Continuity of Rebellion: Guanajuato and Michoacán, 1813-1820" Hispanic American Historical Review 62(1)February 1982, pp. 19–48.

Knight, Alan (2002). Mexico: The Colonial Era. Cambridge University Press.

Timmons, Wilbert H. (1963). Morelos: Priest, Soldier, Statesman of Mexico. El Paso: Texas Western College Press.

Jaime E. Rodríguez O, ed. (1989). The Independence of Mexico and the Creation of the New Nation. UCLA Latin American Studies. Los Angeles: UCLA Latin American Center Publications. ISBN 978-0-87903-070-4.

- Tutino, John. From Insurrection to Revolution in Mexico: Social Bases of Agrarian Violence, 1750-1940. Princeton: Princeton University Press 1986.

External links

- Chieftains of Mexican Independence