Washington Naval Treaty

| Limitation of Naval Armament | |

|---|---|

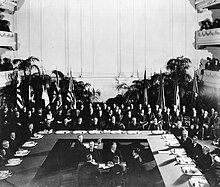

Signing of the Washington Naval Treaty. | |

| Type | Arms control |

| Context | World War I |

| Signed | February 6, 1922 (1922-02-06) |

| Location | Memorial Continental Hall, Washington, D.C. |

| Effective | August 17, 1923 (1923-08-17) |

| Expiration | December 31, 1936 (1936-12-31) |

| Negotiators |

|

| Signatories |

|

| Parties |

|

| Language | English |

The Washington Naval Treaty, also known as the Five-Power Treaty, the Four-Power Treaty, and the Nine-Power Treaty, was a treaty signed during 1922 among the major nations that had won World War I, which agreed to prevent an arms race by limiting naval construction. It was negotiated at the Washington Naval Conference, held in Washington, D.C., from November 1921 to February 1922, and it was signed by the governments of the United Kingdom, the United States, France, Italy, and Japan. It limited the construction of battleships, battlecruisers and aircraft carriers by the signatories. The numbers of other categories of warships, including cruisers, destroyers and submarines, were not limited by the treaty, but those ships were limited to 10,000 tons displacement each.

The treaty was concluded on February 6, 1922. Ratifications of that treaty were exchanged in Washington on August 17, 1923, and it was registered in the League of Nations Treaty Series on April 16, 1924.[1]

Later naval arms limitation conferences sought additional limitations of warship building. The terms of the Washington treaty were modified by the London Naval Treaty of 1930 and the Second London Naval Treaty of 1936. By the mid-1930s, Japan and Italy renounced the treaties, while Germany renounced the Treaty of Versailles which had limited its navy. Naval arms limitation became increasingly difficult for the other signatories.

Contents

1 Background

2 Negotiations

2.1 Capital ships

2.2 Cruisers and destroyers

2.3 Submarines

2.4 Pacific bases

3 Terms

4 Effects

5 Japanese denunciation

6 Influences of cryptography

7 References

8 Sources

9 External links

Background

Immediately after World War I, the United Kingdom had the world's largest and most powerful navy, followed by the United States and more distantly by Japan, France and Italy. The High Seas Fleet of defeated Germany had been interned by the British. The allies had differing opinions concerning the final disposition of the German fleet, with the French and Italians wanting the German fleet divided between the victorious powers and the Americans and British wanting the ships destroyed. These negotiations became mostly moot when the German crews scuttled most of their ships. News of the scuttling angered the French and Italians, with the French particularly unimpressed with British explanations that their fleet guarding the Germans had been away on exercises at the time. Nevertheless, the British joined their allies in condemning the German actions and no credible evidence emerged to suggest that the British had collaborated actively with the Germans with respect to the scuttling. The Treaty of Versailles, signed soon after the scuttling of the German High Seas Fleet, imposed strict limits on the size and number of warships that the newly-installed German government was allowed to build and maintain.[citation needed]

The US, UK, France, Italy, and Japan had been allied for World War I; but with the German threat seemingly finished, a naval arms race between the erstwhile allies seemed likely for the next few years.[2] President Woodrow Wilson's administration had already announced successive plans for the expansion of the US Navy from 1916 to 1919 that would have resulted in a massive fleet of 50 modern battleships.[3]

In response, the Japanese parliament finally authorized construction of warships to enable the Japanese Navy to attain its goal of an "eight-eight" fleet programme, with eight modern battleships and eight battlecruisers. The Japanese started work on four battleships and four battlecruisers, all much larger and more powerful than those of the classes preceding.[4]

The 1921 British Naval Estimates planned four battleships and four battlecruisers, with another four battleships to follow the subsequent year.[2]

The new arms race was unwelcome to the U.S. public. The United States Congress disapproved of Wilson's 1919 naval expansion plan, and during the 1920 presidential election campaign, politics resumed the non-interventionalism of the prewar era, with little enthusiasm for continued naval expansion.[5] Britain also could ill afford any resumption of battleship construction, given the exorbitant cost.[6]

During late 1921, the USA government became aware that Britain was planning a conference to discuss the strategic situation in the Pacific and Far East regions. To forestall the conference and satisfy domestic demands for a global disarmament conference, the Harding administration called the Washington Naval Conference during November 1921.[7]

Negotiations

At the first plenary session held November 21, 1921, US Secretary of State Charles Evans Hughes presented his country's proposals. Hughes provided a dramatic beginning for the conference by stating with resolve: "The way to disarm is to disarm".[8] The ambitious slogan received enthusiastic public endorsement and likely abbreviated the conference while helping ensure his proposals were largely adopted. He subsequently proposed the following:

- A ten-year pause or "holiday" of the construction of capital ships (battleships and battlecruisers), including the immediate suspension of all building of capital ships.

- The scrapping of existing or planned capital ships to give a 5:5:3:1.75:1.75 ratio of tonnage with respect to Britain, the United States, Japan, France and Italy respectively.

- Ongoing limits of both capital ship tonnage and the tonnage of secondary vessels with the 5:5:3 ratio.

Capital ships

The proposals for capital ships were largely accepted by the UK delegation, but they were controversial with the British public. It would no longer be possible for Britain to have adequate fleets in the North Sea, the Mediterranean, and the Far East simultaneously. That provoked outrage from parts of the Royal Navy.[citation needed]

Nevertheless, there was huge demand for the UK to agree. The risk of war with the United States was increasingly regarded as merely theoretical, as there were very few policy differences between the two Anglophone powers. Naval spending was also unpopular in both the UK and its dominions. Furthermore, Britain was implementing major decreases of its budget because of the post–World War I recession.[9]

The Japanese delegation was divided. Japanese naval doctrine required the maintenance of a fleet 70% the size of that of the United States, which was felt to be the minimum necessary to defeat the United States in any subsequent war. The Japanese envisaged two separate engagements, first with the U.S. Pacific Fleet and then with the U.S. Atlantic Fleet. It calculated that a 7:5 ratio in the first battle would produce a big enough margin of victory to be able to win the subsequent engagement and so a 5:3 ratio, or 60%, was unacceptable. Nevertheless, the director of the delegation, Katō Tomosaburō, preferred accepting the latter to the prospect of an arms race with the United States, as the relative industrial strength of the two nations would cause Japan to lose such an arms race and possibly suffer an economic crisis. At the beginning of the negotiations, the Japanese had only 55% of capital ships and 18% of the GDP that the Americans did.[citation needed]

Akagi (a former Japanese battlecruiser converted to an aircraft carrier) being relaunched during April 1925.

His opinion was opposed strongly by Katō Kanji, the president of the Naval Staff College, who acted as his chief naval aide at the delegation and represented the influential "big navy" opinion, which was that in the event of war, the United States would be able to build indefinitely more warships, because of its huge industrial power, and so Japan needed to prepare as thoroughly as possible for the inevitable conflict with America.[citation needed]

Katō Tomosaburō was finally able to persuade the Japanese high command to accept the Hughes proposals, but the treaty was for years a cause of controversy in the navy.[10]

The French delegation initially responded negatively to the idea of reducing its capital ships tonnage to 175,000 tons and demanded 350,000, slightly above Japan. In the end, concessions regarding cruisers and submarines helped persuade the French to agree to the limit on capital ships.[11] Another issue that was considered critical by the French representatives was Italy's request of substantial parity, which was considered unsubstantiated; however, pressure from the US and UK delegations caused them to accept it. That was considered a great success by the Italian government, but parity would never actually be attained.[12]

There was much discussion about the inclusion or exclusion of individual warships. In particular, the Japanese delegation was keen to retain their newest battleship Mutsu, which had been funded with great public enthusiasm, including donations from schoolchildren.[13] That resulted in provisions to allow the United States and Britain to construct equivalent ships.[citation needed]

Cruisers and destroyers

Hawkins lead ship for the Hawkins class cruisers alongside the quay, probably during Interwar period.

Hughes proposed to limit secondary ships (cruisers and destroyers) in the same proportions as capital ships. However, that was unacceptable to both the British and the French. The British counterproposal, in which the British would be entitled to 450,000 tons of cruisers in consideration of its imperial commitments but the United States and Japan only 300,000 and 250,000 respectively, proved equally contentious. Thus, the idea of limiting total cruiser tonnage or numbers was rejected entirely.[11]

Instead, the British suggested a qualitative limit of future cruiser construction. The limit proposed, of a 10,000 ton maximum displacement and 8-inch calibre guns, was intended to allow the British to retain the Hawkins class, then being constructed. That coincided with the USA's requirements for cruisers for Pacific Ocean operations and also with Japanese plans for the Furutaka class. The suggestion was adopted with little debate.[11]

Submarines

A major British demand during the negotiations was the complete abolition of the submarine, which had proved so effective against them in the war. However, that proved impossible, particularly as a result of French opposition; they demanded an allowance of 90,000 tons of submarines[14] and so the conference ended without an agreement for restricting submarines.[15]

Pacific bases

Article XIX of the Treaty also prohibited Britain, Japan, and the United States from constructing any new fortifications or naval bases in the Pacific Ocean region. Existing fortifications in Singapore, the Philippines, and Hawaii could remain. That was a significant victory for Japan, as newly fortified British or American bases would be a serious problem for the Japanese in the event of any future war. That provision of the treaty essentially guaranteed that Japan would be the dominant power in the Western Pacific Ocean and was crucial in gaining Japanese acceptance of the limits on capital ship construction.[16]

Terms

Tonnage limitations | ||

| Country | Capital ships | Aircraft carriers |

|---|---|---|

| British Empire | 525,000 tons (533,000 tonnes) | 135,000 tons (137,000 tonnes) |

| United States | 525,000 tons (533,000 tonnes) | 135,000 tons (137,000 tonnes) |

| Empire of Japan | 315,000 tons (320,000 tonnes) | 81,000 tons (82,000 tonnes) |

| France | 175,000 tons (178,000 tonnes) | 60,000 tons (61,000 tonnes) |

| Italy | 175,000 tons (178,000 tonnes) | 60,000 tons (61,000 tonnes) |

The treaty strictly limited both the tonnage and construction of capital ships and aircraft carriers and included limits of the size of individual ships.

The tonnage limits defined by Articles IV and VII (tabulated) gave a strength ratio of approximately 5:5:3:1.75:1.75 for the UK, the United States, Japan, Italy, and France, respectively.

The qualitative limits of each type of ship were as follows:

- Capital ships (battleships and battlecruisers) were limited to 35,000 tons standard displacement and guns of no larger than 16-inch calibre. (Articles V and VI)

- Aircraft carriers were limited to 27,000 tons and could carry no more than 10 heavy guns, of a maximum calibre of 8 inches. However, each signatory was allowed to use two existing capital ship hulls for aircraft carriers, with a displacement limit of 33,000 tons each (Articles IX and X). For the purposes of the treaty, an aircraft carrier was defined as a warship displacing more than 10,000 tons constructed exclusively for launching and landing aircraft. Carriers lighter than 10,000 tons, therefore, did not count towards the tonnage limits (Article XX, part 4). Moreover, all aircraft carriers then in service or building (Argus, Furious, Langley and Hosho) were declared "experimental" and not counted (Article VIII).

- All other warships were limited to a maximum displacement of 10,000 tons and a maximum gun calibre of 8 inches (Articles XI and XII).

The treaty also detailed by Chapter II the individual ships to be retained by each navy, including the allowance for the United States to complete two further ships of the Colorado class and for the UK to complete two new ships in accordance with the treaty limits.

Chapter II, part 2, detailed what was to be done to render a ship ineffective for military use. In addition to sinking or scrapping, a limited number of ships could be converted as target ships or training vessels if their armament, armour and other combat-essential parts were removed completely. Some could also be converted into aircraft carriers.

Part 3, Section II specified the ships to be scrapped to comply with the treaty and when the remaining ships could be replaced. In all, the United States had to scrap 30 existing or planned capital ships, Britain 23 and Japan 17.

Effects

The treaty arrested the continuing upward trend of battleship size and halted new construction entirely for more than a decade.

The treaty marked the end of a long period of increases of battleship construction. Many ships then being constructed were scrapped or converted into aircraft carriers. Treaty limits were respected and then extended by the London Naval Treaty of 1930. It was not until the mid-1930s that navies began to build battleships once again, and power and size of new battleships began to increase once again. The Second London Naval Treaty of 1936 sought to extend the Washington Treaty limits until 1942, but in the absence of Japan or Italy, it was largely ineffective.[citation needed]

There were fewer effects on cruiser building. While the treaty specified 10,000 tons and 8-inch guns as the maximum size of a cruiser, that was also the minimum size cruiser that any navy was willing to build. The treaty began a building competition of 8-inch, 10,000 ton "treaty cruisers", which gave further cause for concern.[17] Subsequent naval treaties sought to address this, by limiting cruiser, destroyer and submarine tonnage.

Unofficial effects of the treaty included the end of the Anglo-Japanese Alliance. It was not part of the Washington Treaty in any way, but the American delegates had made it clear they would not agree to the treaty unless the UK ended its alliance with the Japanese. [18]

Japanese denunciation

Japanese denunciation of the Washington Naval Treaty, 29 December 1934.

The naval treaty had a profound effect on the Japanese. With superior American and British industrial power, a long war would very likely end in a Japanese defeat. Thus, gaining strategic parity was not economically possible.[citation needed]

Many Japanese considered the 5:5:3 ratio of ships as another snub by the West, though it can be argued that the Japanese had a greater force concentration than the U.S Navy or the Royal Navy. It also contributed to controversy in high ranks of the Imperial Japanese Navy between the Treaty Faction officers and their Fleet Faction opponents, who were also allied with the ultranationalists of the Japanese army and other parts of the Japanese government. For the Treaty Faction, the treaty was one of the factors that contributed to the deterioration of the relationship between the United States and Japanese governments. Some have also argued that the treaty was one major factor in prompting Japanese expansionism by the Fleet Faction during the early 1930s.[19] The perception of unfairness resulted in Japan's renunciation of the Second London Naval Treaty during 1936.

Yamato during sea trials, October 1941. It displaced 72,800 tonnes at full load.

Isoroku Yamamoto, who later masterminded the attack of Pearl Harbor, argued that Japan should remain in the treaty. His opinion was more complex, however, in that he believed the United States could outproduce Japan by a greater factor than the 5:3 ratio because of the huge US production advantage of which he was an expert since he had served with the Japanese embassy in Washington. After the signing of the treaty, he commented, "Anyone who has seen the auto factories in Detroit and the oil-fields in Texas knows that Japan lacks the power for a naval race with America." He later added, "The ratio works very well for Japan – it is a treaty to restrict the other parties."[20] He believed that other methods than a spree of construction would be needed to even the odds, which may have contributed to his advocacy of the plan to attack Pearl Harbor.

On December 29, 1934, the Japanese government gave formal notice that it intended to terminate the treaty. Its provisions remained in force formally until the end of 1936 and were not renewed.[citation needed]

Influences of cryptography

What was unknown to the participants of the Conference was that the American "Black Chamber" (the Cypher Bureau, a US intelligence service), commanded by Herbert Yardley, was spying on the delegations' communications with their home capitals. In particular, Japanese communications were deciphered thoroughly, and American negotiators were able to get the absolute minimum possible deal that the Japanese had indicated they would ever accept.[citation needed]

As it was unpopular with much of the Imperial Japanese Navy and with the increasingly active and important ultranationalist groups, the value that the Japanese government accepted was the cause of much suspicion and accusation among Japanese politicians and naval officers.[citation needed]

References

^ League of Nations Treaty Series, vol. 25, pp. 202–227.

^ ab Marriott 2005, p. 9.

^ Potter 1981, p. 232.

^ Evans & Peattie 1997, p. 174.

^ Potter 1981, p. 233.

^ Kennedy 1983, p. 274.

^ Marriott 2005, p. 10.

^ Jones 2001, p. 119.

^ Kennedy 1983, pp. 275–276.

^ Evans & Peattie 1997, pp. 193–196.

^ abc Marriott 2005, p. 11.

^ Giorgerini, Giorgio (2002). Uomini sul fondo : storia del sommergibilismo italiano dalle origini a oggi. Milano: Mondadori. pp. 84–85. ISBN 978-8804505372..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ Evans & Peattie 1997, p. 197.

^ Marriott 2005, pp. 10–11.

^ Birn, Donald S. (1970). "Open Diplomacy at the Washington Conference of 1921–2: The British and French Experience". Comparative Studies in Society and History. 12 (3): 297. doi:10.1017/S0010417500005879.

^ Evans & Peattie 1997, p. 199.

^ Marriott 2005, p. 3.

^ Howarth 1983, p. 167.

^ Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1922–1946. Conway Maritime Press. 1980. p. 3. ISBN 978-0851771465.

^ Howarth 1983, p. 152.

Sources

Evans, David; Peattie, Mark (1997), Kaigun: Strategy, Tactics and Technology in the Imperial Japanese Navy, 1887–1941, Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, ISBN 978-0-87021-192-8.

Kaufman, Robert Gordon (1990), Arms Control During the Pre-Nuclear Era: The United States and Naval Limitation Between the Two World Wars, New York: Columbia University Press, ISBN 978-0-231-07136-9

Kennedy, Paul (1983), The Rise and Fall of British Naval Mastery, London: Macmillan, ISBN 978-0-333-35094-2

Marriott, Leo (2005), Treaty Cruisers: The First International Warship Building Competition, Barnsley: Pen & Sword, ISBN 978-1-84415-188-2

Potter, E, ed. (1981), Sea Power: A Naval History (2nd ed.), Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, ISBN 978-0-87021-607-7

Jordan, John (2011), Warships after Washington: The Development of Five Major Fleets 1922–1930, Seaforth Publishing, ISBN 978-1-84832-117-5

Jones, Howard (2001), Crucible of power: a history of US foreign relations since 1897, Rowman & Littlefield, ISBN 978-0-8420-2918-6

Howarth, Stephen (1983), The Fighting Ships of the Rising Sun, Atheneum, ISBN 978-0-689-11402-1

Limitation of Naval Armament, treaty, 1922

External links

Wikisource has original text related to this article: Washington Naval Treaty, 1922 |

Conference on the Limitation of Armament (full text). iBiblio. 1922.: the Washington Naval Treaty.

"The New Navies". Popular Mechanics (article): 738–48. May 1929.: on warships provided for under the treaty.- EDSITEment lesson Postwar Disillusionment and the Quest for Peace 1921–1929