Aunt Jemima

| |

| Product type | Pancake mix, syrup, breakfast foods |

|---|---|

| Owner | Quaker Oats |

| Country | United States |

| Introduced | November 1, 1889 (1889-11-01) |

| Website | auntjemima.com |

Aunt Jemima is a brand of pancake mix, syrup, and other breakfast foods owned by the Quaker Oats Company of Chicago, a subsidiary of PepsiCo. The trademark dates to 1893, although Aunt Jemima pancake mix debuted in 1889. The Quaker Oats Company first registered the Aunt Jemima trademark in April 1937.[1] Aunt Jemima originally came from a minstrel show as one of their pantheon of stereotypical Black characters. The character appears to have been a Reconstruction era addition to that cast.[2]

Given its history, some consider the character to be an offensive embodiment of racist stereotypes and attitudes, while others see the brand with nostalgia and object to criticism as political correctness.[3][4][5][6]

Contents

1 History

2 Extended product line

3 Logo

4 Idealization of plantation life

5 Slang

6 In popular culture

7 Lawsuit

8 Pancake Capital of Texas

9 See also

10 References

11 Further reading

12 External links

History

Rutt's recipe from November 1, 1889, on display at Patee House museum in St. Joseph

Advertisement for buckwheat pancake mix, circa 1932

The inspiration for Aunt Jemima was Billy Kersands' American-style minstrelsy/vaudeville song "Old Aunt Jemima", written in 1875. The Aunt Jemima character was prominent in minstrel shows in the late 19th century and was later adopted by commercial interests to represent the Aunt Jemima brand.

Aunt Jemima's character is based on the common stereotype of the mammy archetype, a character in minstrel shows in the late 1800s. Her skin is dark and dewy, with a pearly white smile. She wears a scarf over her head and a polka dot dress with a white collar, similar to the common attire and physical features of "mammy" characters throughout history.[7]

St. Joseph Gazette editor Chris L. Rutt, of St. Joseph, Missouri, and his friend Charles G. Underwood bought a flour mill in 1888. Rutt and Underwood's Pearl Milling Company faced a glutted flour market, so they sold their excess flour as a ready-made pancake mix in white paper sacks with a trade name (which Arthur F. Marquette dubbed the "first ready-mix"[8]).[1][9]

1889 Formula for Aunt Jemima mix:

- 100 lb Hard Winter Wheat

- 100 lb Corn Flour

- 7½ lb B.W.T. Phosphates from Provident Chem[ical] St L[ouis]

- 2¾ lb Bicarb[onate] Soda

- 3 lb Salt.

Rutt reportedly saw a minstrel show featuring the "Old Aunt Jemima" song in the fall of 1889, presented by blackface performers identified by Marquette as "Baker & Farrell".[8] However, Doris Witt was unable to confirm Marquette's account. Witt suggests that Rutt might have witnessed a performance by the vaudeville performer Pete F. Baker, who played a character described in newspapers of that era as "Aunt Jemima". If this is correct, the original inspiration for the Aunt Jemima character was a white male in blackface, whom some have described as a German immigrant.[9] A character named "Aunt Jemima" appeared on the stage in Washington, D.C., as early as 1864.[10]

Ad showing the Aunt Jemima character with apron and kerchief as described, 1909

Marquette recounts that the actor playing Aunt Jemima wore an apron and kerchief, and Rutt appropriated this Aunt Jemima character to market the Pearl Milling Company pancake mix in late 1889 after viewing a minstrel show.[8][11]

However, Rutt and Underwood were unable to make the project work, so they sold their company to the Randolph Truett Davis Milling Company in St. Joseph, Missouri, in 1890.

The R. T. Davis Milling Company hired former slave Nancy Green as a spokesperson for the Aunt Jemima pancake mix in 1890.[1] Nancy Green was born in Montgomery County, Kentucky, and played the Jemima character from 1890 until her death on August 30, 1923. As Jemima, Green operated a pancake-cooking display at the World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago, Illinois, USA in 1893, appearing beside the "world's largest flour barrel". From this point on, marketing materials for the line of products centered around the stereotypical mammy archetype, including the Aunt Jemima marketing slogan first used at the World Fair: "I's in Town, Honey".[9]Anna Julia Cooper used the World's Columbian Exposition as an opportunity to address how young African American women were being exploited by white men.[12] She predicted the appeal of Aunt Jemima and the southern domestic ideal and went on to describe the north's fascination with southern traditions as part of America’s “unwritten history”.[12] Progressive African American women[who?] post emancipation saw Aunt Jemima’s image as a setback that inspired a regression in race relations.

The Davis Milling Company was renamed Aunt Jemima Mills in 1913.[13] The Quaker Oats Company bought the brand in 1926.[1]

No one portrayed Aunt Jemima for ten years following the death of Nancy Green.

In 1933, Quaker Oats hired Anna Robinson to play Aunt Jemima as part of their promotion at the Chicago World Fair in 1933.[1] She was sent to New York City by Lord and Thomas to have her picture taken. "Never to be forgotten was the day they loaded 350 pounds of Anna Robinson on the Twentieth Century Limited."[14] Other photos showing Robinson making pancakes for celebrities and used in advertising "ranked among the highest read of their time".[15]

Anna Short Harrington, born in 1897 in Marlboro County, South Carolina, began her career as Aunt Jemima in 1935. She had to support her five children, and she moved with her family to Syracuse, New York, where she cooked for a living. Quaker Oats discovered her when she was cooking at a fair.[16][17] An ad in Woman's Home Companion in November 1935 said, "Let ol Auntie sing in yo' kitchen."[18] It was her picture with a bandana used on Quaker Oats products.[16] Harrington continued to play the role for 14 years, and she made enough money to buy a large house and rent rooms. That house was demolished to make way for Interstate 81.[18] Harrington died in 1955. According to John Troy McQueen, author of The Story of Aunt Jemima, "she really was famous for cooking pancakes."[16]

The company first registered the Aunt Jemima trademark in 1937.[1]

Ethel Ernestine Harper was Aunt Jemima during the 1950s in person, in print and in media. She was the first Aunt Jemima to be depicted on TV and the final "living person" basis for the Aunt Jemima image until it was changed to a composite in the 1960s.[19] She worked as a traveling "Aunt Jemima" on behalf of the Quaker company, giving presentations at schools, churches and other organizations. Prior to assuming the role, Harper graduated from college at the age of 17 and became a teacher.[20]

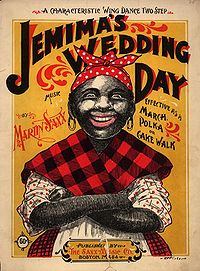

"Jemima" character on 1899 cakewalk sheet music cover

The Aunt Jemima character received the Key to the City of Albion, Michigan, on January 25, 1964. An actress portraying Jemima visited Albion many times for fundraisers.[21]

Just as the formula for the mix has changed several times over the years, so has the Aunt Jemima image been modified several times. In her most recent 1989 makeover, as she reached her 100th anniversary, the 1968 image was updated, with her kerchief removed to reveal a natural hairdo and pearl earrings. The logo much more resembled a modern homemaker than previous designs and carried far fewer racial connotations. This new look remains with the products to this day.[citation needed]

Extended product line

Quaker Oats introduced Aunt Jemima syrup in 1966. This was followed by Aunt Jemima Butter Lite syrup in 1985 and Butter Rich syrup in 1991.[1]

Aunt Jemima frozen foods were licensed out to Aurora Foods in 1996, which in 2004 was absorbed into Pinnacle Foods Corporation. Aunt Jemima Frozen Breakfast is sold in the continental United States where it caters to American tastes.[citation needed]

Logo

The original version of the current Aunt Jemima logo was drawn by H. Gene Miller, but he was never officially credited. He also drew the original version of the current San Giorgio pasta company logo.[citation needed]

James J. Jaffee, a freelance artist from the Bronx, New York also drew one of the original images of Aunt Jemima used by Quaker Oats to market the product in the mid 1900s.

Idealization of plantation life

One interpretation is that Aunt Jemima embodied an early twentieth century idealized domesticity that was inspired by old southern hospitality.[22] There were others that capitalized on this theme, such as Uncle Ben's Rice and Cream of Wheat’s Rastus.[23] The backdrop to the trademark image of Aunt Jemima is a romanticized view of antebellum plantation life. The myth surrounding Aunt Jemima's secret recipe, family life, and plantation life as a happy slave contributes to the post Civil War idealism of southern life and America's developing consumer culture. Early advertisements used an Aunt Jemima paper doll family as an advertising gimmick to buy the product.[22] Aunt Jemima is represented with her husband, Rastus, whose name was later changed to Uncle Mose to avoid confusion with the Cream of Wheat character, and their five children: Abraham, Lincoln, Dilsie, Zeb, and Dinah.[22] The doll family was barefoot and dressed in tattered clothing with the possibility to see them transform from rags to riches by buying another box with civilized clothing cut-outs.[24]

Slang

The term "Aunt Jemima" is sometimes used colloquially as a female version of the derogatory label "Uncle Tom". In this context, the slang term "Aunt Jemima" falls within the "Mammy archetype" and refers to a friendly black woman who is perceived as obsequiously servile or acting in, or protective of, the interests of whites.[25] The 1950s television show Beulah came under fire for depicting a "mammy"-like black maid and cook who was somewhat reminiscent of Aunt Jemima.

In popular culture

The 1933 novel Imitation Of Life by Fannie Hurst features an Aunt Jemima-type character, Delilah, a maid struggling in life with her widowed employer, Bea. Their fortunes change dramatically when Bea capitalizes on Delilah's family pancake recipe to open a pancake restaurant that attracts tourists at the Shore of New Jersey. It becomes a great success and eventually is packaged and sold as Aunt Delilah's Pancake Mix. The Academy Award nominated 1934 film version of Imitation of Life starring Claudette Colbert and Louise Beavers retains this part of the plot, which was excised from the 1959 remake of Imitation of Life starring Lana Turner and directed by Douglas Sirk. They did however achieve success due to selling the flour with a smiling Delilah on the box dressed in Aunt Jemima fashion.

Aunt Jemima, a minstrel-type variety radio program, was broadcast January 17, 1929 – June 5, 1953, at times on CBS and at other times on the Blue Network. The program had several hiatuses during the overall span.[26]

In the 1960s, Betye Saar began collecting images of Aunt Jemima, Uncle Tom, Little Black Sambo, and other stereotyped African-American figures from folk culture and advertising of the Jim Crow era. She incorporated them into collages and assemblages, transforming them into statements of political and social protest.[27] The Liberation of Aunt Jemima is one of her most notable works from this era. In this mixed-media assemblage, Saar utilized the stereotypical mammy figure of Aunt Jemima to subvert traditional notions of race and gender.[28]

Frank Zappa includes a song titled "Electric Aunt Jemima" on his 1969 album Uncle Meat. Electric Aunt Jemima was the nickname for Zappa's Standel guitar amplifier. Zappa's composition "Magdalena" on his 1971 album Just Another Band From L.A. tells the story of a Canadian maple syrup-maker ("...for the pancakes of our land.") who lusts after his teenage daughter. His 1974 album Apostrophe (') continues the pancake and syrup theme on the tracks "St. Alphonzo's Pancake Breakfast" and "Father O'Blivion."

Faith Ringgold’s first quilt story Who's Afraid of Aunt Jemima? (1983) depicts the story of Aunt Jemima as a matriarch restaurateur.

In the South Park episode "Gluten Free Ebola" (2014), Aunt Jemima appears in Eric Cartman's delirious dream to tell him that the food pyramid is upside down.

Lawsuit

On August 5, 2014, descendants of Anna Short Harrington filed a lawsuit in the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Illinois against plaintiffs Quaker Oats and PepsiCo for $2 billion USD. The suit, which also names as defendants Pinnacle Foods and its former suitor Hillshire Brands, accuses the companies of failing to pay Harrington and her heirs an "equitable fair share of royalties" from the pancake mix and syrup brand that uses her likeness and recipes.[29][30] The lawsuit was dismissed with prejudice and without leave to amend on February 18, 2015.[31]

Pancake Capital of Texas

Hawkins, Texas, is not the home of the Aunt Jemima pancake or the place where pancakes were invented. Hawkins is the “Pancake Capital of Texas” because a long time resident of Hawkins, Lillian Richard, portrayed “Aunt Jemima” for Quaker Oats from 1925-1947 and traveled throughout the southern United States promoting the Aunt Jemima pancake. The chamber of commerce decided to use Hawkins’ connection to Aunt Jemima to boost tourism. The designation of “Pancake Capital of Texas” passed the Texas legislature in Senate Resolution No. 73 in 1995 upon the introduction of a resolution by State Senator David Cain, spearheaded by Lillian's niece, Jewell Richard-McCalla, a lifelong resident of Hawkins. A parade was held in Hawkins celebrating this designation and the long time resident who got it all started. The reason given by the chamber and by Senator Cain for the designation, “Hawkins has to be known for something”!

Historical marker dedicated to Lillian Richard, Aunt Jemima portrayer

Lillian was born in 1891 and grew up in the tiny community of Fouke, outside of Hawkins Texas, east of Mineola. She moved to Dallas when she was 20 — where she was hired by Quaker Oats Company to promote making pancakes under the moniker “Aunt Jemima.” She did so for 23 years, until she suffered a stroke in 1948. She returned to Fouke, where she lived for the remainder of her life. She died in 1956 and is buried in the Fouke Memorial Cemetery. Lillian was honored with a Texas Historical Marker dedicated in her name on Saturday June 30, 2012, at a ceremony at the Fouke Community Center, FM 2869, east of Mineola at 10 AM.

See also

- Banania

- Betty Crocker

- Imitation of Life

- Mrs. Butterworth's

- Rastus

- Sarotti

- Uncle Ben's Rice

- Edith Wilson

References

^ abcdefg Aunt Jemima History Archived August 23, 2007, at the Wayback Machine., Quaker Oats website

^ Slave in a Box: The Strange Career of Aunt Jemima, M. M. Manning, University of Virginia Press, Charlottesville, Virginia, 1998, .mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

ISBN 0-8139-1811-1

p68

^ Can We Please, Finally, Get Rid of ‘Aunt Jemima’?

^ New Racism Museum Reveals the Ugly Truth Behind Aunt Jemima

^ Why it's so hard for Aunt Jemima to ditch her unsavory past

^ Patrick, Jeanette (2017), "Aunt Jemima and Betty Crocker: American Cultural Icons that Never Existed", National Women's History Museum

^ Griffin, Johnnie (1998). "Aunt Jemima: Another Image, Another Viewpoint". Journal of Religious Thought. 54/55: 75–77.

^ abc Brands, Trademarks, and Good Will: The Story of the Quaker Oats Company, Arthur F. Marquette, McGraw-Hill, 1967

^ abc from pages 25-31 of Black Hunger: Soul Food and America, Doris Witt, ebrary, Inc, University of Minnesota Press, 2004,

ISBN 0-8166-4551-5,

ISBN 978-0-8166-4551-0

^ Daily National Republican, August 11, 1864

^ The Advertiser's Holy Trinity: Aunt Jemima, Rastus, and Uncle Ben Archived May 7, 2006, at the Wayback Machine., Moss H. Kendrix: A retrospective, The Museum of Public Relations

^ ab Mammy: a century of race, gender, and southern memory, Kimberly Wallace-Sanders, University of Michigan Press – Ann Arbor 1962 p65

^ A History of Northwest Missouri, edited by Walter Williams, The Lewis Publishing Company, 1915.

^ Kern-Foxworth, Marilyn. 1990. "From Plantation Kitchen to American Icon: Aunt Jemima" Archived April 24, 2014, at the Wayback Machine. Public Relations Review. 16 (Fall):59.

^ Marquette, Arthur F. 1967. Brands, Trademarks and Goodwill: The Story of the Quaker Oats Company. New York: McGraw-Hill, p. 154.

^ abc MacCallum, Tom (April 25, 2009). "Aunt Jemima has roots in Richmond County". Richmond County Daily Journal.

[permanent dead link]

^ Sloan, Bob (May 7, 2009). "Book details history of Wallace's own 'Aunt Jemima'". The Cheraw Chronicle. Archived from the original on January 1, 2011. Retrieved August 14, 2013.

^ ab Case, Dick (November 3, 2002). "Book serves up the life of Syracuse's 'Aunt Jemima'". The Post-Standard. Retrieved August 14, 2013.

^ Questia.com

^ Prmuseum.com Archived November 2, 2007, at the Wayback Machine.

^ The Key To The City,

Morning Star, January 7, 2007, pg. 7, Historic Albion Michigan, Albin History/Genealogy Resources, Frank Passic.

^ abc Wallace-Sanders, Kimberly (1962). Mammy: A Century of Race, Gender, and Southern Memory. University of Michigan Press – Ann Arbor. p. 59. ISBN 9780472116140.

^ Wallace-Sanders, Kimberly (1962). Mammy: A Century of Race, Gender, and Southern Memory. University of Michigan Press – Ann Arbor. p. 68. ISBN 9780472116140.

^ "Black ephemera collection is a trove of more than 40,000 items". Antique Trader. August 2, 2010. Retrieved October 22, 2012.

^ Cassell's Dictionary of Slang, Jonathon Green, Cassell, March 1999,

ISBN 0-304-34435-4, p. 36.

^ Dunning, John. (1998). On the Air: The Encyclopedia of Old-Time Radio. Oxford University Press.

ISBN 978-0-19-507678-3. P. 50.

^ "Betye Saar | American artist and educator". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2018-02-17.

^ "Life Is a Collage for Artist Betye Saar". NPR.org. Retrieved 2018-02-17.

^ 'Aunt Jemima' heirs sue Pepsi, Quaker Oats for $2 billion in royalties Fortune. August 11, 2014. Retrieved August 13, 2014.

^ D.W. Hunter, Jr. et al v. PepsiCo Inc. et al Archived September 14, 2014, at the Wayback Machine. RFC Express. August 5, 2014. Retrieved August 13, 2014.

^ "'Aunt Jemima' Heirs' $3B Royalties Suit Against Pepsi Axed". law360.com.

Further reading

Mammy and Uncle Mose: Black Collectibles and American Stereotyping, Kenneth Goings, Indiana University Press, Bloomington, Indiana, 1994,

ISBN 0-253-32592-7

Slave in a Box: The Strange Career of Aunt Jemima, M. M. Manning, University of Virginia Press, Charlottesville, Virginia, 1998,

ISBN 0-8139-1811-1

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Aunt Jemima. |

- Quaker Oats Aunt Jemima website

- Pinnacle Foods Aunt Jemima website

The Progression of Aunt Jemima. American Cultural Icons.

Collection of mid-twentieth century advertising featuring Aunt Jemima. From The TJS Labs Gallery of Graphic Design.

Radio Talk Show Host Calls Rice an "Aunt Jemima", Associated Press, MSNBC, November 19, 2004.

Wallace-Sanders, Kimberly (June 15, 2009). "Southern Memory, Southern Monuments, and the Subversive Black Mammy". Southern Spaces.

- Pancake Capital of Texas

- Texas Honors Lillian Richard as Aunt Jemima with Historical Marker