Phosphate

| |||

| |||

| Names | |||

|---|---|---|---|

Systematic IUPAC name Phosphate[1] | |||

| Identifiers | |||

CAS Number |

| ||

3D model (JSmol) |

| ||

Beilstein Reference | 3903772 | ||

ChEBI |

| ||

ChemSpider |

| ||

Gmelin Reference | 1997 | ||

MeSH | Phosphates | ||

PubChem CID |

| ||

UNII |

| ||

InChI

| |||

SMILES

| |||

| Properties | |||

Chemical formula | PO3− 4 | ||

Molar mass | 94.9714 g mol−1 | ||

Conjugate acid | Hydrogen phosphate | ||

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |||

Infobox references | |||

A phosphate is chemical derivative of phosphoric acid. The phosphate ion, (PO3−

4), is an inorganic chemical, the conjugate base that can form many different salts. In organic chemistry, a phosphate, or organophosphate, is an ester of phosphoric acid. Of the various phosphoric acids and phosphates, organic phosphates are important in biochemistry and biogeochemistry (and, consequently, in ecology), and inorganic phosphates are mined to obtain phosphorus for use in agriculture and industry.[2] At elevated temperatures in the solid state, phosphates can condense to form pyrophosphates.

In biology, adding phosphates to—and removing them from—proteins in cells are both pivotal in the regulation of metabolic processes. Referred to as phosphorylation and dephosphorylation, respectively, they are important ways that energy is stored and released in living systems.

Contents

1 Chemical properties

1.1 Speciation

1.2 Biochemistry of phosphates

2 Occurrence and mining

3 Production

4 Ecology

5 See also

6 References

7 External links

Chemical properties

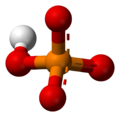

This is the structural formula of the phosphoric acid functional group as found in weakly acidic aqueous solution. In more basic aqueous solutions, the group donates the two hydrogen atoms and ionizes as a phosphate group with a negative charge of 3. [3]

The phosphate ion is a polyatomic ion with the empirical formula PO3−

4 and a molar mass of 94.97 g/mol. It consists of one central phosphorus atom surrounded by four oxygen atoms in a tetrahedral arrangement. The phosphate ion carries a −3 formal charge and is the conjugate base of the hydrogen phosphate ion, HPO2−

4, which is the conjugate base of H

2PO−

4, the dihydrogen phosphate ion, which in turn is the conjugate base of H

3PO

4, phosphoric acid. A phosphate salt forms when a positively charged ion attaches to the negatively charged oxygen atoms of the ion, forming an ionic compound.

Many phosphates are not soluble in water at standard temperature and pressure. The sodium, potassium, rubidium, caesium, and ammonium phosphates are all water-soluble. Most other phosphates are only slightly soluble or are insoluble in water. As a rule, the hydrogen and dihydrogen phosphates are slightly more soluble than the corresponding phosphates. The pyrophosphates are mostly water-soluble. Aqueous phosphate exists in four forms:

- In strongly basic conditions, the phosphate ion (PO3−

4) predominates, - In weakly basic conditions, the hydrogen phosphate ion (HPO2−

4) is prevalent. - In weakly acidic conditions, the dihydrogen phosphate ion (H

2PO−

4) is most common. - In strongly acidic conditions, trihydrogen phosphate (H

3PO

4) is the main form.

H

3PO

4

Phosphoric acid

H

2PO−

4

Dihydrogen phosphate

HPO2−

4

Hydrogen phosphate

PO3−

4

Phosphate

More precisely, considering these three equilibrium reactions:

H

3PO

4 ⇌ H+ + H

2PO−

4

H

2PO−

4 ⇌ H+ + HPO2−

4

HPO2−

4 ⇌ H+ + PO3−

4

the corresponding constants at 25 °C (in mol/L) are (see phosphoric acid):

Ka1=[H+][H2PO4−][H3PO4]≃7.5×10−3{displaystyle K_{mathrm {a1} }={frac {[{mbox{H}}^{+}][{mbox{H}}_{2}{mbox{PO}}_{4}^{-}]}{[{mbox{H}}_{3}{mbox{PO}}_{4}]}}simeq 7.5times 10^{-3}}(pKa1 ≈ 2.12)

Ka2=[H+][HPO42−][H2PO4−]≃6.2×10−8{displaystyle K_{mathrm {a2} }={frac {[{mbox{H}}^{+}][{mbox{HPO}}_{4}^{2-}]}{[{mbox{H}}_{2}{mbox{PO}}_{4}^{-}]}}simeq 6.2times 10^{-8}}(pKa2 ≈ 7.21)

Ka3=[H+][PO43−][HPO42−]≃2.14×10−13{displaystyle K_{mathrm {a3} }={frac {[{mbox{H}}^{+}][{mbox{PO}}_{4}^{3-}]}{[{mbox{HPO}}_{4}^{2-}]}}simeq 2.14times 10^{-13}}(pKa3 ≈ 12.67)

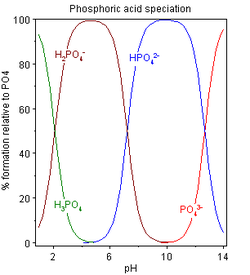

Speciation

The speciation diagram obtained using these pK values shows three distinct regions. In effect, H

3PO

4, H

2PO−

4 and HPO2−

4 behave as separate weak acids because the successive pK values differ by more than 4. For each acid, the pH at half-neutralization is equal to the pK value of the acid. The region in which the acid is in equilibrium with its conjugate base is defined by pH ≈ pK ± 2. Thus, the three pH regions are approximately 0–4, 5–9 and 10–14. This is a simplified model, assuming a constant ionic strength. It will not hold in reality at very low and very high pH values.

For a neutral pH, as in the cytosol, pH = 7.0

- [H2PO4−][H3PO4]≃7.5×104 , [HPO42−][H2PO4−]≃0.62 , [PO43−][HPO42−]≃2.14×10−6{displaystyle {frac {[{mbox{H}}_{2}{mbox{PO}}_{4}^{-}]}{[{mbox{H}}_{3}{mbox{PO}}_{4}]}}simeq 7.5times 10^{4}{mbox{ , }}{frac {[{mbox{HPO}}_{4}^{2-}]}{[{mbox{H}}_{2}{mbox{PO}}_{4}^{-}]}}simeq 0.62{mbox{ , }}{frac {[{mbox{PO}}_{4}^{3-}]}{[{mbox{HPO}}_{4}^{2-}]}}simeq 2.14times 10^{-6}}

so that only H

2PO−

4 and HPO2−

4 ions are present in significant amounts (62% H

2PO−

4, 38% HPO2−

4. Note that in the extracellular fluid (pH = 7.4), this proportion is inverted (61% HPO2−

4, 39% H

2PO−

4).

Phosphate can form many polymeric ions such as pyrophosphate), P

2O4−

7, and triphosphate, P

3O5−

10. The various metaphosphate ions (which are usually long linear polymers) have an empirical formula of PO−

3 and are found in many compounds.

Biochemistry of phosphates

In biological systems, phosphorus is found as a free phosphate ion in solution and is called inorganic phosphate, to distinguish it from phosphates bound in various phosphate esters. Inorganic phosphate is generally denoted Pi and at physiological (homeostatic) pH primarily consists of a mixture of HPO2−

4 and H

2PO−

4 ions.

Inorganic phosphate can be created by the hydrolysis of pyrophosphate, denoted PPi:

P

2O4−

7 + H2O ⇌ 2 HPO2−

4

However, phosphates are most commonly found in the form of adenosine phosphates (AMP, ADP, and ATP) and in DNA and RNA. It can be released by the hydrolysis of ATP or ADP. Similar reactions exist for the other nucleoside diphosphates and triphosphates. Phosphoanhydride bonds in ADP and ATP, or other nucleoside diphosphates and triphosphates, can release high amounts of energy when hydrolyzed which give them their vital role in all living organisms. They are generally referred to as high-energy phosphate, as are the phosphagens in muscle tissue. Compounds such as substituted phosphines have uses in organic chemistry, but do not seem to have any natural counterparts.

The addition and removal of phosphate from proteins in all cells is a pivotal strategy in the regulation of metabolic processes. Phosphorylation and dephosphorylation are important ways that energy is stored and released in living systems. Cells use ATP for this.

Phosphate is useful in animal cells as a buffering agent. Phosphate salts that are commonly used for preparing buffer solutions at cell pHs include Na2HPO4, NaH2PO4, and the corresponding potassium salts.

An important occurrence of phosphates in biological systems is as the structural material of bone and teeth. These structures are made of crystalline calcium phosphate in the form of hydroxyapatite. The hard dense enamel of mammalian teeth consists of fluoroapatite, a hydroxy calcium phosphate where some of the hydroxyl groups have been replaced by fluoride ions.

Plants take up phosphorus through several pathways: the arbuscular mycorrhizal pathway and the direct uptake pathway.

Occurrence and mining

Phosphate mine near Flaming Gorge, Utah, 2008

Train loaded with phosphate rock, Métlaoui, Tunisia, 2012

Phosphates are the naturally occurring form of the element phosphorus, found in many phosphate minerals. In mineralogy and geology, phosphate refers to a rock or ore containing phosphate ions. Inorganic phosphates are mined to obtain phosphorus for use in agriculture and industry.[2]

The largest global producer and exporter of phosphates is Morocco. Within North America, the largest deposits lie in the Bone Valley region of central Florida, the Soda Springs region of southeastern Idaho, and the coast of North Carolina. Smaller deposits are located in Montana, Tennessee, Georgia, and South Carolina. The small island nation of Nauru and its neighbor Banaba Island, which used to have massive phosphate deposits of the best quality, have been mined excessively. Rock phosphate can also be found in Egypt, Israel, Western Sahara, Navassa Island, Tunisia, Togo, and Jordan, countries that have large phosphate-mining industries.

Phosphorite mines are primarily found in:

North America: United States, especially Florida, with lesser deposits in North Carolina, Idaho, and Tennessee

Africa: Morocco, Algeria, Egypt, Western Sahara, Niger, Senegal, Togo, Tunisia.

Middle East: Israel, Saudi Arabia, Jordan, Syria, Iran and Iraq, at the town of Akashat, near the Jordanian border.

Central Asia: Kazakhstan

Oceania: Australia, Makatea, Nauru, and Banaba Island

In 2007, at the current rate of consumption, the supply of phosphorus was estimated to run out in 345 years.[4] However, some scientists thought that a "peak phosphorus" will occur in 30 years and Dana Cordell from Institute for Sustainable Futures said that at "current rates, reserves will be depleted in the next 50 to 100 years".[5] Reserves refer to the amount assumed recoverable at current market prices, and, in 2012, the USGS estimated 71 billion tons of world reserves, while 0.19 billion tons were mined globally in 2011.[6] Phosphorus comprises 0.1% by mass of the average rock[7] (while, for perspective, its typical concentration in vegetation is 0.03% to 0.2%),[8] and consequently there are quadrillions of tons of phosphorus in Earth's 3 * 1019 ton crust,[9] albeit at predominantly lower concentration than the deposits counted as reserves from being inventoried and cheaper to extract; if it is assumed that the phosphate minerals in phosphate rock are hydroxyapatite and fluoroapatite, phosphate minerals contain roughly 18.5% phosphorus by weight and if phosphate rock contains around 20% of these minerals, the average phosphate rock has roughly 3.7% phosphorus by weight.

Some phosphate rock deposits are notable for their inclusion of significant quantities of radioactive uranium isotopes. This syndrome is noteworthy because radioactivity can be released into surface waters[10] in the process of application of the resultant phosphate fertilizer (e.g. in many tobacco farming operations in the southeast US).

In December 2012, Cominco Resources announced an updated JORC compliant resource of their Hinda project in Congo-Brazzaville of 531 Mt, making it the largest measured and indicated phosphate deposit in the world.[11]

Production

The three principal phosphate producer countries (China, Morocco and the United States) account for about 70% of world production.

| Country | Production (millions kg) | Mondial part (%) | Mondial reserves (millions kg) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1,200 | 0.54 | 2,200,000 | |

| 2,600 | 1.17 | 1,030,000 | |

| 6,700 | 3.00 | 315,000 | |

| 100,000 | 44.83 | 3,700,000 | |

| 5,500 | 2.47 | 1,250,000 | |

| 1,100 | 0.49 | 65,000 | |

| 200 | 0.09 | 430,000 | |

| 3,300 | 1.48 | 130,000 | |

| 7,500 | 3.36 | 1,300,000 | |

| 1,600 | 0.72 | 260,000 | |

| 1,700 | 0.76 | 30,000 | |

| 30,000 | 13.45 | 50,000,000 | |

| 4,000 | 1.79 | 820,000 | |

| 12,500 | 5.60 | 1,300,000 | |

| 3,300 | 1.48 | 956,000 | |

| 1,000 | 0.45 | 50,000 | |

| 2,200 | 0.99 | 1,500,000 | |

| 750 | 0.34 | 1,800,000 | |

| 1,000 | 0.45 | 30,000 | |

| 4,000 | 1.79 | 100,000 | |

| 27,600 | 12.37 | 1,100,000 | |

| 2,700 | 1.21 | 30,000 | |

| Other countries | 2,600 | 1.17 | 380,000 |

| Total | 223,000 | 100 | 69,000,000 |

Ecology

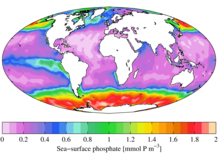

Sea surface phosphate from the World Ocean Atlas

Relationship of phosphate to nitrate uptake for photosynthesis in various regions of the ocean. Note that nitrate is more often limiting than phosphate. See the Redfield ratio.

In ecological terms, because of its important role in biological systems, phosphate is a highly sought after resource. Once used, it is often a limiting nutrient in environments, and its availability may govern the rate of growth of organisms. This is generally true of freshwater environments, whereas nitrogen is more often the limiting nutrient in marine (seawater) environments. Addition of high levels of phosphate to environments and to micro-environments in which it is typically rare can have significant ecological consequences. For example, blooms in the populations of some organisms at the expense of others, and the collapse of populations deprived of resources such as oxygen (see eutrophication) can occur. In the context of pollution, phosphates are one component of total dissolved solids, a major indicator of water quality, but not all phosphorus is in a molecular form that algae can break down and consume.[13]

Calcium hydroxyapatite and calcite precipitates can be found around bacteria in alluvial topsoil.[14] As clay minerals promote biomineralization, the presence of bacteria and clay minerals resulted in calcium hydroxyapatite and calcite precipitates.[14]

Phosphate deposits can contain significant amounts of naturally occurring heavy metals. Mining operations processing phosphate rock can leave tailings piles containing elevated levels of cadmium, lead, nickel, copper, chromium, and uranium. Unless carefully managed, these waste products can leach heavy metals into groundwater or nearby estuaries. Uptake of these substances by plants and marine life can lead to concentration of toxic heavy metals in food products.[15]

See also

Pyrophosphate – P

2O4−

7

Polyphosphate – P

nO(n+2)−

3n+1

Metaphosphate – P

nOn−

3n

- Fertilizer

Hypophosphite – H

2PO−

2

Organophosphorus compounds- Phosphate – OP(OR)3, such as triphenyl phosphate

- Phosphate conversion coating

Phosphate soda, a soda fountain beverage

Phosphinate – OP(OR)R2

Phosphine – PR3

Phosphine oxide – OPR3

Phosphinite – P(OR)R2

Phosphite – P(OR)3

- Phosphogypsum

Phosphonate – OP(OR)2R

Phosphonite – P(OR)2R- Phosphorylation

Diammonium phosphate - (NH4)2HPO4

Disodium phosphate – Na2HPO4

Monosodium phosphate – NaH2PO4

Sodium tripolyphosphate – Na5P3O10

- Ouled Abdoun Basin

References

^ "Phosphates – PubChem Public Chemical Database". The PubChem Project. USA: National Center of Biotechnology Information..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ ab "Phosphate Primer". Florida Industrial and Phosphate Research Institute. Florida Polytechnic University. Archived from the original on 29 August 2017.

^ Campbell, Neil A.; Reece, Jane B. (2005). Biology (Seventh ed.). San Francisco, California: Benjamin Cummings. p. 65. ISBN 0-8053-7171-0.

^ Reilly, Michael (May 26, 2007). "How Long Will it Last?". New Scientist. 194 (2605): 38–9. Bibcode:2007NewSc.194...38R. doi:10.1016/S0262-4079(07)61508-5.

^ Leo Lewis (2008-06-23). "Scientists warn of lack of vital phosphorus as biofuels raise demand". The Times.

^ U.S. Geological Survey Phosphate Rock

^ U.S. Geological Survey Phosphorus Soil Samples

^ Floor Anthoni. "Abundance of Elements". Seafriends.org.nz. Retrieved 2013-01-10.

^ American Geophysical Union, Fall Meeting 2007, abstract #V33A-1161. Mass and Composition of the Continental Crust

^ C. Michael Hogan (2010). Mark McGinley and C. Cleveland (Washington, DC.: National Council for Science and the Environment), ed. "Water pollution". Encyclopedia of Earth. Archived from the original on 2010-09-16.

^ "Updated Hinda Resource Announcement: Now world's largest phosphate deposit (04/12/2012)". Cominco Resources.

^ USGS Minerals Year Book - Phosphate Rock

^ Hochanadel, Dave (December 10, 2010). "Limited amount of total phosphorus actually feeds algae, study finds". Lake Scientist. Retrieved June 10, 2012.[B]ioavailable phosphorus – phosphorus that can be utilized by plants and bacteria – is only a fraction of the total, according to Michael Brett, a UW engineering professor ...

^ ab Schmittner KE, Giresse P (1999). "Micro-environmental controls on biomineralization: superficial processes of apatite and calcite precipitation in Quaternary soils, Roussillon, France". Sedimentology. 46 (3): 463–76. Bibcode:1999Sedim..46..463S. doi:10.1046/j.1365-3091.1999.00224.x.

^ Gnandi, K.; Tchangbedjil, G.; Killil, K.; Babal, G.; Abbel, E. (March 2006). "The Impact of Phosphate Mine Tailings on the Bioaccumulation of Heavy Metals in Marine Fish and Crustaceans from the Coastal Zone of Togo". Mine Water and the Environment. 25 (1): 56–62. doi:10.1007/s10230-006-0108-4.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Phosphates. |

US Minerals Databrowser provides data graphics covering consumption, production, imports, exports and price for phosphate and 86 other minerals

Phosphate: analyte monograph – The Association for Clinical Biochemistry and Laboratory Medicine

![frac{[mbox{H}_2mbox{PO}_4^-]}{[mbox{H}_3mbox{PO}_4]}simeq 7.5times10^4 mbox{ , }frac{[mbox{HPO}_4^{2-}]}{[mbox{H}_2mbox{PO}_4^-]}simeq 0.62 mbox{ , } frac{[mbox{PO}_4^{3-}]}{[mbox{HPO}_4^{2-}]}simeq 2.14times10^{-6}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/45a9d19f1b88c87266cfed4a37fe44e445609353)