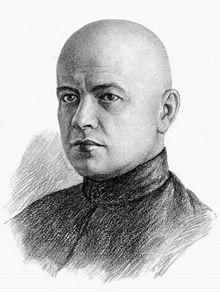

Stanislav Kosior

Stanisław Kosior | |

|---|---|

| |

First Secretary of the Communist Party (Bolsheviks) of Ukraine | |

In office 14 July 1928 – 27 January 1938 | |

| Preceded by | Lazar Kaganovich |

| Succeeded by | Nikita Khrushchev |

In office 25 March 1920 – 17 October 1920 | |

| Preceded by | Nikolay Bestchetvertnoi |

| Succeeded by | Vyacheslav Molotov |

In office 30 May 1919 – 10 December 1919 | |

| Preceded by | Georgiy Pyatakov |

| Succeeded by | Rafail Farbman |

| Candidate member of the 15th Politburo | |

In office 19 December 1927 – 13 July 1930 | |

| Full member of the 14th, 15th Secretariat | |

In office 1 January 1926 – 12 July 1928 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Stanislav Vikentyevich Kosior (1889-11-18)18 November 1889 Węgrów, Siedlce Governorate, Russian Empire |

| Died | 26 February 1939(1939-02-26) (aged 49) Moscow, Soviet Union |

| Nationality | Russian/Soviet |

| Alma mater | Sulin industrial elementary school |

| Signature |  |

Stanisław Vikentyevich Kosior, sometimes spelled Kossior (18 November 1889 – 26 February 1939) was one of three Kosior brothers, ethnically Polish Soviet politicians. He was General Secretary of the Ukrainian Communist Party, deputy prime minister of the USSR and member of the Politburo of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU). He was executed during the Great Purge.

Biography

Stanisław Kosior was born in 1889 in Węgrów in the Siedlce Governorate of the Russian Empire, in the region of Podlachia, to a Polish family of humble factory workers. Because of poverty, he emigrated to Yuzovka (modern Donetsk), where he worked at a steel mill. In 1907 he joined the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party and quickly became the head of the local branch of the party. He was arrested and sacked from his job in the party later that year, and the following year felt obliged to leave the area due to police activity. He used connections to get re-appointed at the Sulin factory in 1909, but was soon arrested again and deported to the Pavlovsk mine.[1] In 1913 he was transferred to Moscow and then to Kiev and Kharkiv, where he organized local Communist cells. In 1915 he was arrested by the Okhrana (the Russian secret police) and exiled to Siberia.

After the February Revolution Kosior moved to Petrograd, where he headed the local branch of the Bolsheviks and the Narva municipal committee. After the October Revolution Kosior moved to the German-controlled areas of the Ober-Ost and Ukraine, where he worked for the Bolshevik cause. After the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, he moved back to Russia, where in 1920 he became Secretary of the CPSU. In 1922 he became head of the Siberian branch of the CPSU. From 1925 to 1928 he was Secretary of the Central Committee of the CPSU.

From 1919, Kosior was for some time a member of Ukraine's Politburo. In 1928 he became General Secretary of the Ukrainian SSR Communist Party. Among his tasks was the collectivization of agriculture in Ukraine.

In 1930 Kosior was admitted to the Politburo of the CPSU. In 1935 he was awarded the Order of Lenin "for remarkable success in the field of agriculture".[2] In January 1938 he also became head of the Soviet Control Office and deputy prime minister of the USSR. This was the peak of his political success.

On 3 May 1938, during the Great Purge, Kosior was stripped of all Party posts and arrested by the NKVD. "Stanislav Kosior withstood brutal tortures [at the hands of the NKVD] but cracked when his sixteen-year-old daughter was brought into the room and raped in front of him."[3] On 26 February 1939 he was sentenced to death by shooting and executed the same day by General Vasili Blokhin.[citation needed] Other Politburo members purged in this period were Jānis Rudzutaks, Roberts Eihe, Vlas Chubar and Pavel Postyshev.[citation needed]

After Stalin's death, Kosior was rehabilitated by the Soviet government on 14 March 1956. After the fall of the USSR, on 13 January 2010, Kosior was condemned by the Court of Appeals of independent Ukraine as a political criminal for organizing mass famine in Ukraine in 1932–1933; the court quashed criminal proceedings due to his death.[4]

References

^ Haupt, Georges & Marie, Jean-Jacques (1974). Makers of the Russian revolution. London: George Allen & Unwin. p. 149. ISBN 0801408091..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ Guide to the history of the Communist Party and the Soviet Union 1898 – 1991. knowbysight.info

^ Figes, Orlando (2007) The Whisperers, Allen Lane, London,

ISBN 0312428030, p. 248

^ Kyiv court accuses Stalin leadership of organizing famine, Kyiv Post (13 January 2010)

External links

Media related to Stanislaw Kosior at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Stanislaw Kosior at Wikimedia Commons