Staple food

Various types of potatoes

Unprocessed seeds of spelt, a historically important staple food

A staple food, food staple, or simply a staple, is a food that is eaten routinely and in such quantities that it constitutes a dominant portion of a standard diet for a given people, supplying a large fraction of energy needs and generally forming a significant proportion of the intake of other nutrients as well. A staple food of a specific society may be eaten as often as every day or every meal, and most people live on a diet based on just a small number of food staples.[1] Specific staples vary from place to place, but typically are inexpensive or readily available foods that supply one or more of the macronutrients needed for survival and health: carbohydrates, proteins, and fats. Typical examples include tubers and roots, grains, legumes, and seeds.

Early agricultural civilizations valued the foods that they established as staples because, in addition to providing necessary nutrition, they generally are suitable for storage over long periods of time without decay. Such nonperishable foods are the only possible staples during seasons of shortage, such as dry seasons or cold temperate winters, against which times harvests have been stored. During seasons of plenty, wider choices of foods may be available.

Staple foods are derived either from vegetables or animal products, and common staples include cereals (such as rice, wheat, maize, millet, or sorghum), starchy tubers or root vegetables (such as potatoes, cassava, sweet potatoes, yams, or taro), meat, fish, eggs, milk, and cheese.[1] Other staple foods include pulses (dried legumes),[2]sago (derived from the pith of the sago palm tree),[3] and fruits (such as breadfruit and plantains). Staple foods may also include (depending on the region): olive oil, coconut oil and sugar (e.g. from plantains).[4][5][6]

Contents

1 Demographics

2 Production

3 Processing

4 Nutrition

4.1 Comparison of 10 staple foods

5 Images

6 See also

7 References

Demographics

@media all and (max-width:720px){.mw-parser-output .tmulti>.thumbinner{width:100%!important;max-width:none!important}.mw-parser-output .tmulti .tsingle{float:none!important;max-width:none!important;width:100%!important;text-align:center}}

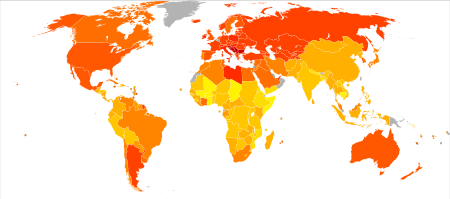

No data

<1600

1600-1800

1800-2000

2000-2200

2200-2400

2400-2600

2600-2800

2800-3000

3000-3200

3200-3400

3400-3600

>3600

Of the more than 50,000 edible plant species in the world, only a few hundred contribute significantly to human food supplies. Although there are over 10,000 species in the cereal family, just a few have been widely cultivated over the past 2,000 years.

The dominant staple foods in different parts of the world are a function of weather patterns, local terrain, farming constraints, acquired tastes and ecosystems. For example, the main energy source staples in the average African diet are cereals (46 percent), roots and tubers (20 percent) and animal products (7 percent). In Western Europe the main staples in the average diet are animal products (33 percent), cereals (26 percent), and roots and tubers (4 percent).

Most of the human population lives on a diet based on one or more of the following staples: cereals (rice, wheat, maize (corn), millet, and sorghum), roots and tubers (potatoes, cassava, yams and taro), and animal products such as meat, milk, eggs, cheese and fish. Regional staples include the plants rye, soybeans, barley, oats, and teff.

Just 15 plant crops provide 90 percent of the world's food energy intake (exclusive of meat), with rice, maize, and wheat comprising 2/3 of human food consumption. These three are the staples of about 80 percent of the world population,[7] and rice feeds almost half of humanity.

Roots and tubers, meanwhile, are important staples for over one billion people in the developing world, accounting for roughly 40 percent of the food eaten by half the population of sub-Saharan Africa. Roots and tubers are high in carbohydrates, calcium, and vitamin C, but low in protein. Cassava root, for example, is a major food staple in the developing world, a basic food source for around 500 million people.

With economic development and free trade, many countries have shifted away from low-nutrient-density staple foods to higher-nutrient-density staples, as well as towards greater meat consumption. Despite this trend, there is growing recognition of the importance of traditional staple crops in nutrition.[citation needed] Agriculture constantly seeks to identify better plant strains with superior nutrition, disease resistance, and higher yields.[citation needed]

Some foods like quinoa—a pseudocereal grain that originally came from the Andes—were also staples centuries ago.[8]Oca tubers, ulluku tubers and grain amaranth are other foods claimed to be historical Andean staples.[9]Pemmican made from dried meat and fat was a staple of the Plains Indians of North America.[10] In 2010, the global consumption of "speciality grains", such as quinoa, was very small compared to other staples, such as rice, wheat, and maize.[citation needed] These grains, once popular, are being reevaluated and reintroduced to certain markets.[citation needed]

Production

Most staple food is currently produced using modern, conventional farming practices. However, the production of staple food using organic farming methods is growing.

| World production, 2012[12] | Average world yield, 2010 | World's most productive countries,[13] 2012[14] | World's largest producing countries, 2013[15] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Crop | (metric tons) | (tons per hectare) | (tons per hectare) | Country | (metric tons) | Country |

| 1 | Maize (Corn) | 873 million | 5.1 | 25.9 | United States | 354 million | United States |

| 2 | Rice | 738 million | 4.3 | 9.5 | Egypt | 204 million | China |

| 3 | Wheat | 671 million | 3.1 | 8.9 | New Zealand | 122 million | China |

| 4 | Potatoes | 365 million | 17.2 | 45.4 | Netherlands | 96 million | China |

| 5 | Cassava | 269 million | 12.5 | 34.8 | Indonesia | 47 million | Nigeria |

| 6 | Soybeans | 241 million | 2.4 | 4.4 | Egypt | 91 million | United States |

| 7 | Sweet potatoes | 108 million | 13.5 | 33.3 | Senegal | 71 million | China |

| 8 | Yams | 59.5 million | 10.5 | 28.3 | Colombia | 36 million | Nigeria |

| 9 | Sorghum | 57.0 million | 1.5 | 86.7 | United States | 10 million | United States |

| 10 | Plantain | 37.2 million | 6.3 | 31.1 | El Salvador | 9 million | Uganda |

Processing

Rice is most commonly cooked and eaten as separate entire grains, but most other staple cereals are milled into a flour or meal that can be used to make bread, noodles, pasta, porridge and mushes like mealie pap. Root vegetables can be mashed and used to make porridge-like dishes such as poi and fufu. Pulses (such as chickpeas, from which gram flour is made) and starchy root vegetables (such as canna rhizomes) can also be made into flour.

Nutrition

Plant-based food staples may not provide a full range of nutrients. The nutrient-deficiency disease pellagra is associated with a diet consisting primarily of maize, while the disease beriberi is associated with a diet of refined white rice.[16]Scurvy can result from a lack of vitamin C, also known as ascorbic acid. One author indicated that the nutritional value of some staple foods are negatively impacted by higher levels of carbon dioxide, as occurs in climate change.[17]

Comparison of 10 staple foods

The following table shows the nutrient content of 10 major staple vegetable foods in raw form, with the caveat that raw grains are not edible and cannot be digested. Raw grains must be cooked, sprouted, or otherwise prepared for human consumption. In sprouted and cooked form, the relative nutritional and anti-nutritional contents of each of these grains is different from that of the raw form of these grains, as shown. Potatoes also must be cooked, but should not be sprouted. Note that the highlighted values show the highest nutrient density among these 10 staples. Other foods, consumed in smaller quantities, may have nutrient densities different from these values.

| Nutrient | Maize (corn)[A] | Rice, white[B] | Wheat[C] | Potatoes[D] | Cassava[E] | Soybeans, green[F] | Sweet potatoes[G] | Yams[Y] | Sorghum[H] | Plantain[Z] | RDA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Water (g) | 10 | 12 | 13 | 79 | 60 | 68 | 77 | 70 | 9 | 65 | 3000 |

| Energy (kJ) | 1528 | 1528 | 1369 | 322 | 670 | 615 | 360 | 494 | 1419 | 511 | 8368–10,460 |

Protein (g) | 9.4 | 7.1 | 12.6 | 2.0 | 1.4 | 13.0 | 1.6 | 1.5 | 11.3 | 1.3 | 50 |

Fat (g) | 4.74 | 0.66 | 1.54 | 0.09 | 0.28 | 6.8 | 0.05 | 0.17 | 3.3 | 0.37 | 44–77 |

Carbohydrates (g) | 74 | 80 | 71 | 17 | 38 | 11 | 20 | 28 | 75 | 32 | 130 |

Fiber (g) | 7.3 | 1.3 | 12.2 | 2.2 | 1.8 | 4.2 | 3 | 4.1 | 6.3 | 2.3 | 30 |

Sugar (g) | 0.64 | 0.12 | 0.41 | 0.78 | 1.7 | 0 | 4.18 | 0.5 | 0 | 15 | minimal |

| Minerals | [A] | [B] | [C] | [D] | [E] | [F] | [G] | [Y] | [H] | [Z] | RDA |

Calcium (mg) | 7 | 28 | 29 | 12 | 16 | 197 | 30 | 17 | 28 | 3 | 1000 |

Iron (mg) | 2.71 | 0.8 | 3.19 | 0.78 | 0.27 | 3.55 | 0.61 | 0.54 | 4.4 | 0.6 | 8 |

Magnesium (mg) | 127 | 25 | 126 | 23 | 21 | 65 | 25 | 21 | 0 | 37 | 400 |

Phosphorus (mg) | 210 | 115 | 288 | 57 | 27 | 194 | 47 | 55 | 287 | 34 | 700 |

Potassium (mg) | 287 | 115 | 363 | 421 | 271 | 620 | 337 | 816 | 350 | 499 | 4700 |

Sodium (mg) | 35 | 5 | 2 | 6 | 14 | 15 | 55 | 9 | 6 | 4 | 1500 |

Zinc (mg) | 2.21 | 1.09 | 2.65 | 0.29 | 0.34 | 0.99 | 0.3 | 0.24 | 0 | 0.14 | 11 |

Copper (mg) | 0.31 | 0.22 | 0.43 | 0.11 | 0.10 | 0.13 | 0.15 | 0.18 | - | 0.08 | 0.9 |

Manganese (mg) | 0.49 | 1.09 | 3.99 | 0.15 | 0.38 | 0.55 | 0.26 | 0.40 | - | - | 2.3 |

Selenium (μg) | 15.5 | 15.1 | 70.7 | 0.3 | 0.7 | 1.5 | 0.6 | 0.7 | 0 | 1.5 | 55 |

| Vitamins | [A] | [B] | [C] | [D] | [E] | [F] | [G] | [Y] | [H] | [Z] | RDA |

Vitamin C (mg) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 19.7 | 20.6 | 29 | 2.4 | 17.1 | 0 | 18.4 | 90 |

Thiamin (B1) (mg) | 0.39 | 0.07 | 0.30 | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.44 | 0.08 | 0.11 | 0.24 | 0.05 | 1.2 |

Riboflavin (B2) (mg) | 0.20 | 0.05 | 0.12 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.18 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.14 | 0.05 | 1.3 |

Niacin (B3) (mg) | 3.63 | 1.6 | 5.46 | 1.05 | 0.85 | 1.65 | 0.56 | 0.55 | 2.93 | 0.69 | 16 |

Pantothenic acid (B5) (mg) | 0.42 | 1.01 | 0.95 | 0.30 | 0.11 | 0.15 | 0.80 | 0.31 | - | 0.26 | 5 |

Vitamin B6 (mg) | 0.62 | 0.16 | 0.3 | 0.30 | 0.09 | 0.07 | 0.21 | 0.29 | - | 0.30 | 1.3 |

Folate Total (B9) (μg) | 19 | 8 | 38 | 16 | 27 | 165 | 11 | 23 | 0 | 22 | 400 |

Vitamin A (IU) | 214 | 0 | 9 | 2 | 13 | 180 | 14187 | 138 | 0 | 1127 | 5000 |

Vitamin E, alpha-tocopherol (mg) | 0.49 | 0.11 | 1.01 | 0.01 | 0.19 | 0 | 0.26 | 0.39 | 0 | 0.14 | 15 |

Vitamin K1 (μg) | 0.3 | 0.1 | 1.9 | 1.9 | 1.9 | 0 | 1.8 | 2.6 | 0 | 0.7 | 120 |

Beta-carotene (μg) | 97 | 0 | 5 | 1 | 8 | 0 | 8509 | 83 | 0 | 457 | 10,500 |

Lutein+zeaxanthin (μg) | 1355 | 0 | 220 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 30 | 6,000 |

| Fats | [A] | [B] | [C] | [D] | [E] | [F] | [G] | [Y] | [H] | [Z] | RDA |

Saturated fatty acids (g) | 0.67 | 0.18 | 0.26 | 0.03 | 0.07 | 0.79 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.46 | 0.14 | minimal |

Monounsaturated fatty acids (g) | 1.25 | 0.21 | 0.2 | 0.00 | 0.08 | 1.28 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.99 | 0.03 | 22–55 |

Polyunsaturated fatty acids (g) | 2.16 | 0.18 | 0.63 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 3.20 | 0.01 | 0.08 | 1.37 | 0.07 | 13–19 |

| [A] | [B] | [C] | [D] | [E] | [F] | [G] | [Y] | [H] | [Z] | RDA |

A raw yellow dent corn | B raw unenriched long-grain white rice |

C raw hard red winter wheat | D raw potato with flesh and skin |

E raw cassava | F raw green soybeans |

G raw sweet potato | H raw sorghum |

Y raw yam | Z raw plantains |

/* unofficial |

Images

White rice, boiled

Bread made from wheat flour (contains gluten)

Maize (corn)

Edamame (green soybeans)

Kidney beans

Sorghum seeds and popped sorghum

Amaranth (left) and common wheat berries

Millet grains

Colored quinoa

Cassava roots

Chinese yams

Sweet potato salad

Ulluco tubers

Oca tubers

Taro roots

Potatoes

Plantain and banana

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Staple food. |

- Cash crop

- Famine food

- Vavilov centers

References

^ ab United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization: Agriculture and Consumer Protection. "Dimensions of Need - Staples: What do people eat?". Retrieved 15 October 2010..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ "Around the world in dishes made with pulses". Food and Agricultural Organisation of the United Nations. 18 November 2015. Retrieved 23 September 2017.

^ The Sago Palm: The Food and Environmental Challenges of the 21st Century. Kyoto University Press. 2015. p. 331. ISBN 978-1-920901-13-4.

^ "African Food Staples". Retrieved 29 May 2015.

^ "Olive Oil & Health - All Olive Oil". Retrieved 29 May 2015.

^ "How Sugar Went From a Condiment to a Diet Staple".

^ "Dimensions of Need: An atlas of food and agriculture". Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. 1995.

^ E.A. Oelke; et al. "Quinoa". University of Minnesota.

^ Arbizu and Tapia (1994). "Plant Production and Protection Series No. 26. FAO, Rome, Italy". FAO / Purdue University.

^ John E. Foster. "Pemmican". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved 29 May 2015.

^ Allianz. "Food security: Ten Crops that Feed the World". Allianz.

^ "Food and Agricultural commodities production / Commodities by regions". Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. 2012.

^ The numbers in this column are country average; regional farm productivity within the country varies, with some farms even higher.

^ "FAOSTAT: Production-Crops, 2010 data". Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. 2011.

^ "Food and Agricultural commodities production / Countries by commodity (2013 data)". Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Retrieved 24 April 2016.

^ United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization: Agriculture and Consumer Protection. "Rice and Human Nutrition" (PDF). Retrieved 15 October 2010.

^ Wernick, Adam (29 October 2017). "Global warming threatens nutrition levels in staple crops". Public Radio International (PRI). Retrieved 30 October 2017.

^ "Nutrient data laboratory". United States Department of Agriculture. Retrieved August 10, 2016.