Zero of a function

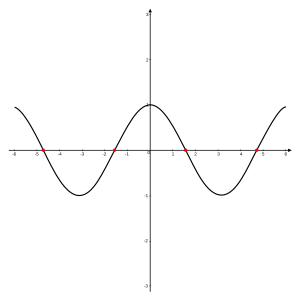

for x{displaystyle x}

for x{displaystyle x} in [−2π,2π]{displaystyle left[-2pi ,2pi right]}

in [−2π,2π]{displaystyle left[-2pi ,2pi right]}![{displaystyle left[-2pi ,2pi right]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/cdc6c1efef56b12d350b9e16f34e39e317d5b51f) , with zeros at −3π2,−π2,π2{displaystyle -{tfrac {3pi }{2}},;-{tfrac {pi }{2}},;{tfrac {pi }{2}}}

, with zeros at −3π2,−π2,π2{displaystyle -{tfrac {3pi }{2}},;-{tfrac {pi }{2}},;{tfrac {pi }{2}}} , and 3π2,{displaystyle {tfrac {3pi }{2}},}

, and 3π2,{displaystyle {tfrac {3pi }{2}},} marked in red.

marked in red.In mathematics, a zero, also sometimes called a root, of a real-, complex- or generally vector-valued function f{displaystyle f}

In other words, a "zero" of a function is an input value that produces an output of 0{displaystyle 0}

A root of a polynomial is a zero of the corresponding polynomial function.

The fundamental theorem of algebra shows that any non-zero polynomial has a number of roots at most equal to its degree and that the number of roots and the degree are equal when one considers the complex roots (or more generally the roots in an algebraically closed extension) counted with their multiplicities. For example, the polynomial f{displaystyle f}

- f(x)=x2−5x+6{displaystyle f(x)=x^{2}-5x+6}

has the two roots 2{displaystyle 2}

f(2)=22−5⋅2+6=0andf(3)=32−5⋅3+6=0{displaystyle f(2)=2^{2}-5cdot 2+6=0quad {textrm {and}}quad f(3)=3^{2}-5cdot 3+6=0}.

If the function maps real numbers to real numbers, its zeros are the x{displaystyle x}

Contents

1 Solution of an equation

2 Polynomial roots

2.1 Fundamental theorem of algebra

3 Computing roots

4 Zero set

4.1 Applications

5 See also

6 References

7 Further reading

Solution of an equation

Every equation in the unknown x may be rewritten as

- f(x)=0{displaystyle f(x)=0}

by regrouping all terms in the left-hand side. It follows that the solutions of such an equation are exactly the zeros of the function f{displaystyle f}

Polynomial roots

Every real polynomial of odd degree has an odd number of real roots (counting multiplicities); likewise, a real polynomial of even degree must have an even number of real roots. Consequently, real odd polynomials must have at least one real root (because one is the smallest odd whole number), whereas even polynomials may have none. This principle can be proven by reference to the intermediate value theorem: since polynomial functions are continuous, the function value must cross zero in the process of changing from negative to positive or vice versa.

Fundamental theorem of algebra

The fundamental theorem of algebra states that every polynomial of degree n{displaystyle n}

Computing roots

Computing roots of functions, for example polynomial functions, frequently requires the use of specialised or approximation techniques (for example, Newton's method). However, some polynomial functions, including all those of degree no greater than 4, can have all their roots expressed algebraically in terms of their coefficients. (See algebraic solution.)

Zero set

In various areas of mathematics, the zero set of a function is the set of all its zeros. More precisely, if f:X→R{displaystyle f:Xto mathbb {R} }

The term zero set is generally used when there are infinitely many zeros, and they have some non-trivial topological properties. For example, a level set of a function f{displaystyle f}

Applications

In algebraic geometry, the first definition of an algebraic variety is through zero sets. Specifically, an affine algebraic set is the intersection of the zero sets of several polynomials in a polynomial ring k[x1,…,xn]{displaystyle kleft[x_{1},ldots ,x_{n}right]}![{displaystyle kleft[x_{1},ldots ,x_{n}right]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/26e790118352b6852ad6a2e132d4c9819b896c45)

In analysis and geometry, any closed subset of Rn{displaystyle mathbb {R} ^{n}}

In differential geometry, zero sets are frequently used to define manifolds. An important special case is the case that f{displaystyle f}

For example, the unit m{displaystyle m}

See also

- Zeros and poles

- Sendov's conjecture

- Marden's theorem

- Vanish at infinity

- Zero crossing

References

^ ab Foerster, Paul A. (2006). Algebra and Trigonometry: Functions and Applications, Teacher's Edition (Classics ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. p. 535. ISBN 0-13-165711-9..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

Further reading

- Weisstein, Eric W. "Root". MathWorld.