Chatham Islands

| Native name: Rēkohu / Wharekauri | |

|---|---|

Satellite photograph of the archipelago. The two largest islands are Chatham Island, followed by Pitt Island to the southeast | |

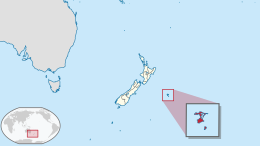

Location of the Chatham Islands in the Pacific Ocean | |

| Geography | |

| Location | Southern Pacific Ocean |

| Coordinates | 44°02′S 176°26′W / 44.033°S 176.433°W / -44.033; -176.433Coordinates: 44°02′S 176°26′W / 44.033°S 176.433°W / -44.033; -176.433 |

| Archipelago | Chatham Islands |

| Total islands | 10 |

| Major islands | Chatham Island, Pitt Island |

| Area | 966 km2 (373 sq mi) |

| Highest elevation | 299 m (981 ft) |

| Administration | |

New Zealand | |

| Largest settlement | Waitangi |

| Demographics | |

| Population | 600 (2013 census) |

| Additional information | |

| Time zone |

|

| • Summer (DST) |

|

The Chatham Islands form an archipelago in the Pacific Ocean about 800 kilometres (500 mi) east of the South Island of New Zealand. It consists of about ten islands within a 40-kilometre (25 mi) radius, the largest of which are Chatham Island and Pitt Island. Some of these islands, once cleared for farming, are now preserved as nature reserves to conserve some of the unique flora and fauna.

The resident population is 600 (as of 2013[update]).[1] The islands' economy is largely dependent on conservation, tourism, farming, and fishing.

The archipelago is called Rēkohu ("Misty Sun") in the indigenous Moriori language, and Wharekauri in Māori. The Moriori are the indigenous people of the Chatham Islands; they arrived on the islands around 1500 and eventually developed a peaceful way of life. In 1835 members of the Māori Ngāti Mutunga and Ngāti Tama tribes invaded the island and nearly exterminated Moriori, enslaving the survivors. Chatham Islands have officially been part of New Zealand since 1842 and in 1863 the Moriori were released from slavery.[2]

Chatham islands includes the New Zealands's easternmost point, the Forty-Fours. Local administration is provided by the Chatham Islands Council, whose powers are similar to other unitary authorities. The islands are listed with the New Zealand Outlying Islands. The islands are an immediate part of New Zealand, but are not part of any region or district. They are instead an Area Outside Territorial Authority, like all the other outlying islands except the Solander Islands.

Contents

1 Geography

1.1 Climate

1.2 Chathams time

1.3 Geology

2 Ecology

3 History

3.1 Moriori

3.2 European arrival

3.3 Māori settlement

3.4 1880s to today

3.4.1 Moriori community

4 Population

5 Transport

6 Government

6.1 Electorates

6.2 Local government

6.3 State services

6.4 Health

6.5 Education

7 Economy

7.1 Electricity generation

8 See also

9 References

10 Bibliography

11 Film

12 Further reading

13 External links

Geography

Topographic map of the Chatham Islands

The islands are at about 43°53′S 176°31′W / 43.883°S 176.517°W / -43.883; -176.517, roughly 840 kilometres (520 mi) east of Christchurch, New Zealand. The nearest mainland New Zealand point to the Chatham Islands is Cape Turnagain, in the North Island at a distance of 650 kilometres (400 mi). The nearest mainland city to the islands is Hastings, New Zealand, located 697 kilometres (430 mi) to the North-West. The two largest islands, Chatham Island and Pitt Island, constitute most of the total area of 966 square kilometres (373 sq mi), with a dozen scattered islets covering the rest.

The islands sit on the Chatham Rise, a large, relatively shallowly submerged (no more than 1,000 metres or 3,281 feet deep at any point) part of the Zealandia continent that stretches east from near the South Island. The Chatham Islands, which emerged only within the last four million years, are the only part of the Chatham Rise showing above sea level.[3]

The islands are hilly with coasts being a varied mixture including cliffs and dunes, beaches, and lagoons. Pitt is more rugged than Chatham, although the highest point (299 metres or 981 feet) is on a plateau near the southernmost point of the main island (at 44°07′12″S 176°34′38″W / 44.12000°S 176.57722°W / -44.12000; -176.57722, 1.5 kilometres (0.93 mi) south of Lake Te Rangatapu).[4] The plateau is dotted with numerous lakes and lagoons, flowing mainly from the island's nearby second highest point, Maungatere Hill, at 294 metres.[5] Notable are the large Te Whanga Lagoon, and Huro and Rangitahi. Chatham has a number of streams, including Te Awainanga and Tuku.

Chatham and Pitt are the only inhabited islands, with the remaining smaller islands being conservation reserves with restricted or prohibited access. The livelihoods of the inhabitants depend on agriculture, with the island being an exporter of coldwater crayfish, and increasing tourism.

The names of the main islands, in the order of occupation are:

| English name | Moriori name | Māori name | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chatham Island | Rekohu | Wharekauri | |

| Pitt Island | Rangiaotea | Rangiauria | |

| South East Island | Rangatira | Rangatira | |

| The Fort | Mangere | Mangere | The Māori name has supplanted the English name for this island. |

| Little Mangere | Unknown | Tapuenuku | |

| Star Keys | Motuhope | Motuhope | |

| The Sisters | Rangitatahi | Rangitatahi | about 16 kilometres (9.9 mi) north of Cape Pattison, a headland in the northwestern part of Chatham Island |

| Forty-Fours | Motchuhar | Motuhara | the easternmost point of New Zealand, about 50 kilometres (31 mi) from Chatham Island. |

Climate

Chatham Islands have an oceanic climate[6] characterised by a narrow temperature range and relatively frequent rainfall. Its isolated position far from any sizeable landmass renders the record temperature for main settlement Waitangi to be just 23.8 °C (74.8 °F).[7] The climate is cool, wet and windy, with average high temperatures between 15 and 20 °C (59 and 68 °F) in summer, and between 5 and 10 °C (41 and 50 °F) in July, the Southern Hemisphere winter. Snow is extremely rare, being recorded near sea level in July 2015 after several decades.[8]

| Climate data for Chatham Islands (1981−2010) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 17.9 (64.2) | 18.2 (64.8) | 17.1 (62.8) | 14.9 (58.8) | 13.0 (55.4) | 11.3 (52.3) | 10.5 (50.9) | 11.0 (51.8) | 11.9 (53.4) | 13.1 (55.6) | 14.4 (57.9) | 16.4 (61.5) | 14.1 (57.4) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 14.9 (58.8) | 15.2 (59.4) | 14.3 (57.7) | 12.4 (54.3) | 10.6 (51.1) | 9.1 (48.4) | 8.2 (46.8) | 8.6 (47.5) | 9.4 (48.9) | 10.6 (51.1) | 11.7 (53.1) | 13.5 (56.3) | 11.5 (52.7) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 11.9 (53.4) | 12.3 (54.1) | 11.5 (52.7) | 9.9 (49.8) | 8.1 (46.6) | 6.8 (44.2) | 5.9 (42.6) | 6.2 (43.2) | 6.9 (44.4) | 8.0 (46.4) | 9.1 (48.4) | 10.7 (51.3) | 9.0 (48.2) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 54.9 (2.16) | 63.9 (2.52) | 84.7 (3.33) | 75.7 (2.98) | 87.9 (3.46) | 107.8 (4.24) | 84.7 (3.33) | 84.4 (3.32) | 71.1 (2.80) | 63.4 (2.50) | 66.7 (2.63) | 66.3 (2.61) | 911.3 (35.88) |

| Average rainy days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 7.9 | 7.7 | 11.3 | 11.1 | 14.4 | 16.0 | 14.8 | 14.5 | 11.9 | 11.2 | 9.8 | 9.4 | 140.1 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 82.2 | 83.5 | 83.2 | 83.4 | 85.7 | 85.8 | 86.9 | 85.8 | 83.4 | 84.0 | 82.5 | 82.7 | 84.1 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 191.3 | 145.5 | 124.2 | 106.3 | 81.2 | 61.8 | 74.4 | 101.0 | 109.1 | 129.7 | 148.9 | 164.0 | 1,437.3 |

| Source: NIWA Science climate data[9] | |||||||||||||

Chathams time

The International Date Line lies to the east of the Chathams, even though the islands lie east of 180° longitude. The Chathams observe their own time, 45 minutes ahead of New Zealand time, including during periods of daylight saving time; the Chatham Standard Time Zone is distinctive as one of very few that differ from others by a period other than a whole hour or half-hour. (New Zealand Time orients itself to 180° longitude.)

Geology

The Chatham Islands are part of the, now largely submerged, continent of Zealandia and are the only part of the Chatham Rise above sea level. This places the Chatham Islands far from the Australian-Pacific plate boundary that dominates the rest of New Zealand's geology. The islands' stratigraphy consists of a Mesozoic schist basement, typically covered by marine sedimentary rocks.[10] Both these sequences are intruded by a series of basalt eruptions. Volcanic activlity has occurred multiple times since the Cretaceous,[11] however, there is currently no active volcanism near any part of the Chatham Rise.

Ecology

Massive phytoplankton bloom around the islands

Chatham Islands Forget-me-not (Myosotidium hortensia)

A weka on Chatham Island

The natural vegetation of the islands was a mixture of forest, scrubby heath, and swamp, but today most of the land is fern or pasture-covered, although there are some areas of dense forest and areas of peat bogs and other habitats. Of interest are the akeake trees, with branches trailing almost horizontally in the lee of the wind.[12] The ferns in the forest understory include Blechnum discolor.

The islands are home to a rich bio-diversity including about fifty endemic plants adapted to the cold and the wind, such as Chatham Islands forget-me-not (Myosotidium hortensia), Chatham Islands sow-thistle (Embergeria grandifolia), rautini (Brachyglottis huntii), Chatham Islands kakaha (Astelia chathamica), soft speargrass (Aciphylla dieffenbachii), and Chatham Island akeake or Chatham Island tree daisy (Olearia traversiorum).

The islands are a breeding ground for huge flocks of seabirds and are home to a number of endemic birds, some of which are seabirds and others which live on the islands. The best known species are the magenta petrel (IUCN classification CR]) and the black robin (IUCN classification EN), both of which came perilously close to extinction before drawing the attention of conservation efforts. Other endemic species are the Chatham oystercatcher, the Chatham gerygone, Chatham pigeon, Forbes' parakeet, the Chatham snipe and the shore plover. The endemic Chatham shag[13] (IUCN classification CR), Pitt shag[14] (IUCN classification EN) and the Chatham albatross[15] (IUCN classification VU) are at risk of capture by a variety of fishing gear, including fishing lines, trawls, gillnets, and pots.[16]

For accounts and notes on seabird species seen in the Chathams between 1960 and 1993 online.[17]

A number of species have gone extinct since human settlement, including the three endemic species of rails, the Chatham raven, and the Chatham fernbird.

Also, a number of marine mammals are found in the waters of the Chathams, including New Zealand sea lions, leopard seals, and southern elephant seals. Many whale species are attracted to the rich food sources of the Chatham Rise.[18]

Much of the natural forest of these islands has been cleared for farming, but Mangere and Rangatira Islands are now preserved as nature reserves to conserve some of these unique flora and fauna. Another threat to wildlife comes from introduced species which prey on the indigenous birds and reptiles, whereas on Mangere and Rangatira, livestock has been removed and native wildlife is recovering.

History

Moriori tree carving, or dendroglyph, found in the Chatham Islands

Moriori

The first human inhabitants of the Chathams were Polynesian tribes who settled the islands about 1500 CE,[19] and in their isolation became the Moriori. The former belief, which arose in the 1800s, was that the original Moriori migrated directly from the more northerly Polynesian islands, just as with the settlement of New Zealand by the ancestors of the Māori. However, linguistic research indicates instead that the ancestral Moriori were Māori wanderers from New Zealand.[20][21][22][23]

As Howe (2003) puts it,

Scholarship over the past 40 years has radically revised the model offered a century earlier by Smith: the Moriori as a pre-Polynesian people have gone (the term Moriori is now a technical term referring to those ancestral Māori who settled the Chatham Islands).'[24]

The plants cultivated by the Māori arrivals were ill-suited for the colder Chathams, so the Moriori lived as hunter-gatherers and fishermen. While their new environment deprived them of the resources with which to build ocean-going craft for long voyages, the Moriori invented what was known as the waka korari, a semi-submerged craft, constructed of flax and lined with air bladders from kelp. This craft was used to travel to the outer islands on 'birding' missions.[23] The Moriori society was a peaceful society and bloodshed was outlawed by the chief Nunuku after generations of warfare. Arguments were solved by consensus or by duels rather than warfare, but at the first sign of bloodshed, the fight was over.

European arrival

The name "Chatham Islands" comes from the ship HMS Chatham[25] of the Vancouver Expedition, whose captain William R. Broughton landed on 29 November 1791, claimed possession for Great Britain and named the islands after the First Lord of the Admiralty, John Pitt, 2nd Earl of Chatham. A relative of his, Thomas Pitt, was a member of the Vancouver Expedition. Sealers and whalers soon started hunting in the surrounding ocean with the islands as their base. It is estimated that 10 to 20 percent of the indigenous Moriori soon died from diseases introduced by foreigners. The sealing and whaling industries ceased activities about 1861, while fishing remained as a major economic activity.

Chatham Islands date their anniversary on 29 November, and observe it 30 November.

Māori settlement

On 19 November and 5 December 1835, about 900 Ngāti Mutunga and Ngāti Tama previously resident in Te Whanganui-A-Tara (Wellington) and led by the chief Matioro arrived on the brig Lord Rodney. The first mate of the ship had been 'kidnapped and threatened with death' unless the captain took the Māori settlers on board. The group, which included men, women and children, brought with them 78 tonnes of seed potato, 20 pigs and seven large canoes called waka.[26]

The incoming Māori were received and initially cared for by the local Moriori. Soon, Ngāti Mutunga and Ngāti Tama began to takahi, or walk the land, to lay claim to it. When it became clear that the visitors intended to stay, the Moriori withdrew to their marae at te Awapatiki. There, after holding a hui (consultation) to debate what to do about the Māori settlers, the Moriori decided to keep with their policy of non-aggression.

Ngāti Mutunga and Ngāti Tama in turn saw the meeting as a precursor to warfare on the part of Moriori and responded. The Māori attacked and in the ensuing action killed over 260 Moriori. A Moriori survivor recalled: "[The Māori] commenced to kill us like sheep... [We] were terrified, fled to the bush, concealed ourselves in holes underground, and in any place to escape our enemies. It was of no avail; we were discovered and killed — men, women and children — indiscriminately." A Māori chief, Te Rakatau Katihe, said: "We took possession ... in accordance with our custom, and we caught all the people. Not one escaped. Some ran away from us, these we killed; and others also we killed — but what of that? It was in accordance with our custom."[citation needed] Despite the Chatham Islands being made part of New Zealand in 1842, Māori kept Moriori slaves until 1863.

After the killings, Moriori were forbidden to marry Moriori, or to have children with each other. All became slaves of the Māori until the 1860s.[27] Many died in despair. Many Moriori women had children by their Māori masters. A number of Moriori women eventually married either Māori or European men. Some were taken away from the Chathams and never returned. Ernst Dieffenbach, who visited the Chathams on a New Zealand Company ship in 1840, reported that the Moriori were the virtual slaves of Māori and were severely mistreated, with death being a blessing. By the time the slaves were released in 1862, only 160 remained, hardly 10% of the 1835 population.[26]

In early May 1838 (some reports say 1839 but this is contradicted by ship records[28]) the French whaling vessel Jean Bart anchored off Waitangi to trade with the Māori. The number of Māori boarding frightened the French, escalating into a confrontation in which the French crew were killed and the Jean Bart was run aground at Ocean Bay, to be ransacked and burned by Ngāti Mutunga. When word of the incident reached the French naval corvette Heroine in the Bay of Islands in September 1838, it set sail for the Chathams, accompanied by the whalers Adele and Rebecca Sims. The French arrived on 13 October and, after unsuccessfully attempting to entice some Ngāti Tama aboard, proceeded to bombard Waitangi. The next morning about a hundred armed Frenchmen went ashore, burning buildings, destroying waka, and seizing pigs and potatoes. The attacks mostly affected Ngāti Tama, weakening their position relative to Ngāti Mutunga.[28][29]

In 1840, Ngāti Mutunga decided to attack Ngāti Tama at their pa. They built a high staging next to the pa so they could fire down on their former allies. Fighting was still in progress when the New Zealand Company ship Cuba arrived as part of a scheme to buy land for settlement. The Treaty of Waitangi, at that stage, did not apply to the islands. The company negotiated a truce between the two warring tribes. In 1841, the New Zealand Company had proposed to establish a German colony on the Chathams. The proposal was discussed by the directors and John Ward signed an agreement with Karl Sieveking of Hamburg on 12 September 1841. However, when the Colonial Office said that the islands were to be part of the colony of New Zealand and any Germans settling there would be treated as aliens, Joseph Somes claimed that Ward had been acting on his own initiative. The proposed leader John Beit and the expedition went to Nelson instead.[30]

The company was then able to purchase large areas of land at Port Hutt (which the Māori called Whangaroa) and Waitangi from Ngāti Mutunga and also large areas of land from Ngāti Tama. This did not stop Ngāti Mutunga from trying to get revenge for the death of one of their chiefs. They were satisfied after they killed the brother of a Ngāti Tama chief. The tribes agreed to an uneasy peace which was finally confirmed in 1842.[31]

Reluctant to give up slavery, Matioro and his people chartered a brig in late 1842 and sailed to Auckland Island. While Matioro was surveying the island, two of the chiefs who had accompanied him decided the island was too inhospitable for settlement, and set sail before he had returned, stranding him and his followers until Pākehā settlers arrived in 1849.[32]

An all-male group of German Moravian missionaries arrived in 1843.[33] When a group of women were sent out to join them three years later, several marriages ensued; a few members of the present-day population can trace their ancestry back to those missionary families.

In 1865, the Māori leader Te Kooti was exiled on the Chatham Islands along with a large group of Māori rebels called the Hauhau, followers of Pai Mārire who had murdered missionaries and fought against government forces mainly on the East Coast of the North Island of New Zealand. The rebel prisoners were paid one shilling a day to work on sheep farms owned by the few European settlers. Sometimes they worked on road and track improvements. They were initially guarded by 26 guards, half of whom were Māori. They lived in whare along with their families. The prisoners helped build a redoubt of stone surrounded by a ditch and wall. Later, they built three stone prison cells. In 1868 Te Kooti and the other prisoners commandeered a schooner and escaped back to the North Island.

Almost all the Māori returned to Taranaki in the 1860s, some after a tsunami in 1868.[34]

1880s to today

The economy of the Chatham Islands, then dominated by the export of wool, suffered under the international depression of the 1880s, only rebounding with the building of fish freezing plants at the island villages of Ōwenga and Kaingaroa.[35] The wharf at Waitangi was first built around the year 1934. However, with the sinking of the Chatham Islands supply ship during the Second World War in 1940 it saw little use by ships. A flying-boat service was set up soon after the sinking for supplies and transport. This continued till 1966 when it was replaced with conventional aircraft.

After the Second World War the island economy suffered again due to its isolation and government subsidies became necessary. This led to many young Chatham Islanders leaving for the mainland. A public radio link to the mainland was built in 1953 and an island phone system in 1962. There was a brief crayfish boom which helped stabilize the economy in the late 1960s and early 1970s. From the early 2000s cattle became a major component of the local economy.[34]

Moriori community

The Moriori community is organised as the Hokotehi Moriori Trust.[36] The Moriori have received recognition from the Crown and the New Zealand government and some of their claims against those institutions for the generations of neglect and oppression have been accepted and acted on. Moriori are recognised as the original people of Rekohu. The Crown also recognised the Ngāti Mutunga Māori[37] as having indigenous status in the Chathams by right of 160-odd years of occupation.

The population of the islands is around 600, including members of both ethnic groups. In January 2005, the Moriori celebrated the opening of the new Kopinga Marae (meeting house).[38]

Modern descendants of the 1835 Māori conquerors claimed a share in ancestral Māori fishing rights. This claim was granted. Now that the primordial population, the Moriori, have been recognised to be former Māori—over the objections of some of the Ngāti Mutunga—they too share in the ancestral Māori fishing rights. Both groups have been granted fishing quotas.[citation needed]

Population

An agricultural scene on the islands

| Historical population | ||

|---|---|---|

| Year | Pop. | ±% p.a. |

| 1986 | 775 | — |

| 1991 | 760 | −0.39% |

| 1996 | 739 | −0.56% |

| 2001 | 717 | −0.60% |

| 2006 | 609 | −3.21% |

| 2013 | 600 | −0.21% |

| Source: [39][40] | ||

Chatham and Pitt Islands are inhabited, with 600 residents in the 2013 Census.[39] The town of Waitangi is the main settlement with some 200 residents. There are other villages such as Owenga, Te One and Kaingaroa, where there are two primary schools. A third school is on Pitt Island. There are also the fishing villages of Owenga and Port Hutt.[39]

Waitangi facilities include a hospital with resident doctor, bank, several stores, and engineering and marine services. The main shipping wharf is located here.

According to the 2013 census there were 264 occupied dwellings, 69 unoccupied dwellings, and 3 dwellings under construction.[39]

Of the residential population, 315 (52.5%) were male compared to 48.7% nationally, and 285 (47.5%) were female, compared to 51.3% nationally. The archipelago had a median age of 41.5 years, 3.5 years above the national median age of 38.0 years. People aged 65 and over made up 12.0% of the population, compared to 14.3% nationally, and people under 15 years made up 20.0%, compared to 20.4% nationally.[39]

The Chatham Islands' ethnicity is made up of (national figures in brackets): 73.5% European (74.0%), 59.3% Māori (14.9%), 1.1% Pacific Islanders (7.4%), 0.5% Asian (11.8%), 0.0% Middle Eastern, Latin American or African (1.2%), and 3.2% other (1.7%). Note that where a person reported more than one ethnic group, they have been counted in each applicable group. As a result, percentages do not add up to 100.[39]

The unemployment rate is of 2.5% of people 15 years and over, compared to 7.4% nationally. The median annual income of all people 15 years and over was $31,500, compared to $28,500 nationally. Of those, 31.0% earned under $20,000, compared to 38.2% nationally, while 31.0% earned over $50,000, compared to 26.7% nationally.[39]

Transport

Visitors to the Chathams generally arrive in the islands via Tuuta Airport.

Visitors to the Chathams usually arrive by air from Auckland, Christchurch or Wellington (around 1.5 – 2 hours from Christchurch on a Convair 580) to Tuuta Airport on Chatham Island. While freight generally arrives by ship (2 days sailing time), the sea journey takes too long for many passengers, and is not always available.[41][42]

The Chathams are part of New Zealand so there are no border controls or formalities on arrival, but visitors are advised to have prearranged their accommodation on the islands. Transport operators may refuse to carry passengers without accommodation bookings. There is no scheduled public transport but accommodation providers are normally able to arrange transport.

Tasman Empire Airways Ltd (TEAL) initially serviced the Chathams by air using flying boats. With the withdrawal of TEAL, the RNZAF maintained an infrequent service with Short Sunderland flying boats. NZ4111 was damaged on takeoff from Te Whanga Lagoon on 4 November 1959 and remains as a wreck on the island. The last flight by RNZAF flying boats was on 22 March 1967.[43] For many years Bristol Freighter aircraft served the islands, a slow and noisy freight aircraft converted for carrying passengers by installing a removable passenger compartment equipped with airline seats and a toilet in part of the cargo hold. The air service primarily served to ship out high-value export crayfish products.

The grass landing field at Hapupu, at the northern end of the Island, proved a limiting factor, as few aircraft apart from the Bristol Freighter had both the range to fly to the islands and the ruggedness to land on the grass airstrip. Although other aircraft did use the landing field occasionally, they would often require repairs to fix damage resulting from the rough landing. Hapupu is also the site of the JM Barker (Hapupu) National Historic Reserve (one of only two in New Zealand) where there are momori rakau (Moriori tree carvings).

In 1981, after many years of requests by locals and the imminent demise of the ageing Bristol Freighters, the construction of a sealed runway at Karewa, Tuuta Airport, allowed more modern aircraft to land safely. The Chathams' own airline, Air Chathams, now operates services to Auckland on Thursdays, Wellington on Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays and Christchurch on Tuesdays. The timetable varies seasonally, but generally planes depart the Chathams around 10.30 am (Chathams Time) and arrive in the mainland around noon. There they refuel and reload, and depart again at around 1 pm back to the Chathams. Air Chathams operates twin turboprop Convair 580 aircraft in combi (freight and passenger) configurations and Fairchild Metroliners.

The ship Rangatira provided a freight service from Timaru to the Chatham Islands from March 2000 to August 2015.[44] The MV Southern Tiare provides a freight service between Napier, Timaru and the Chathams.[42]

There is a small section of tar sealed road between Waitangi and Te One, but the majority of the islands' roads are gravel.

Government

Chatham Islands Flag (unofficial, but widely used on the Islands)

Electorates

Until the 1980s, the Chathams were in the Lyttelton electorate, but since then they have formed part of the Rongotai general electorate, which mostly lies in Wellington. Paul Eagle is the MP for Rongotai. The Te Tai Tonga Māori seat (held since 2011 by Rino Tirikatene) includes the Chatham Islands.

Local government

Local government on the islands, uniquely within New Zealand, involves a council established by its own Act of Parliament, the Chatham Islands Council Act 1995 (Statute No 041, Commenced: 1 November 1995).[45] The Chatham Islands Council[46] operates as a district council with regional council functions, making it in effect a unitary authority but with not quite as many responsibilities as the others. The Council comprises a Mayor and eight Councillors, one of whom is also Deputy Mayor.[47] Certain regional council functions are being administered by Environment Canterbury, the Canterbury Regional Council.

In the 2010 local government elections, Chatham Islands had NZ's highest rate of returned votes, with 71.3 percent voting.[48]

State services

Policing is carried out by a sole-charge constable appointed by the Wellington police district, who has often doubled as an official for many government departments, including court registrar (Department for Courts), customs officer (New Zealand Customs Service) and immigration officer (Department of Labour – New Zealand Immigration Service).

A District Court judge sent from either the North Island or the South Island presides over court sittings, but urgent sittings may take place at the Wellington District Court.

Because of the isolation and small population, some of the rules governing daily activities undergo a certain relaxation. For example, every transport service operated solely on Great Barrier Island, the Chatham Islands or Stewart Island/Rakiura need not comply with section 70C of the Transport Act 1962 (the requirements for drivers to maintain driving-hours logbooks). Drivers subject to section 70B must nevertheless keep record of their driving hours in some form.[49]

Health

From 1 July 2015 the Canterbury District Health Board assumed responsibility from the Hawkes Bay District Health Board for providing publicly funded health services for the island.[50]

Education

Three schools are located on the Chathams, at Kaingaroa, Te One, and Pitt Island. Pitt Island and Kaingaroa are staffed by sole charge principals, while Te One has three teachers and a principal. These schools cater for children from year 1 to 8. No secondary school is present on the Chathams. The majority of secondary school-aged students leave the island for boarding schools in mainland New Zealand. A small number remain on the island and carry out their secondary education through correspondence.

Economy

Most of the Chatham Island economy is based on fishing and crayfishing, with only a fragment of the economic activity in adventure tourism. This economic mix has been stable for the past 50 years, as little infrastructure or population is present to engage in higher levels of industrial or telecommunications activity.[51]

Air Chathams has its head office in Te One.[52]

Electricity generation

Two 225-kW wind turbines and diesel generators provide power on Chatham island, at costs of five to ten times that of electricity on the main islands of New Zealand.[53] During 2014, 65% of the electricity was generated from diesel generators, the balance from wind.[54]

See also

- Chatham Islands penguin

- Flora of the Chatham Islands

- History of Chatham Islands numismatics

- List of islands

References

^ "2013 Census QuickStats about a place: Chatham Islands Territory". Statistics New Zealand. Retrieved 16 December 2017..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ Davis, Denise; Solomon, Māui. "Moriori - The impact of new arrivals". Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 8 December 2018.

^ McGlone, Matt (21 September 2007). "Ecoregions: The Chatham Islands". Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 2009-02-08.

^ New Zealand topographic map of Lake Te Rangatapu area

^ "Chatham Islands Conservation Management Strategy" (PDF). Department of Conservation. p. 32. Retrieved 17 October 2017.

^ "Waitangi, Northland, New Zealand Climate Summary". Weatherbase. Retrieved 11 January 2015.

^ "Waitangi, Northland, New Zealand Temperature Averages". Weatherbase. Retrieved 11 January 2015.

^ "Drought, cyclone then snow for Chathams farms". 2015-08-25.

^ "Climate Data and Activities". NIWA Science. 2007-02-27. Retrieved 15 October 2013.

^ Adams, C J; et al. (1979). "Age and correlation of volcanic rocks of Campbell Island and Metamorphic basement of the Campbell Plateau, South-west Pacific". New Zealand Journal of Geology and Geophysics. 22 (6): 679–691. doi:10.1080/00288306.1979.10424176.

^ Hoernle, K.; White, J.D.L.; Van Den Bogaard, P.; Hauff, F.; Coombs, D.S.; Werner, R.; Timm, C.; Garbe-Schönberg, D.; Reay, A.; Cooper, A.F. (2006-08-15). "Cenozoic intraplate volcanism on New Zealand: Upwelling induced by lithospheric removal". Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 248 (1–2): 350–367. doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2006.06.001. ISSN 0012-821X.

^ Richards, Rhys. "Chatham Islands - Overview". Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 29 December 2016.

^ "Chatham Shag (Phalacrocorax onslowi) - BirdLife species factsheet". Birdlife.org. Retrieved 2015-08-27.

^ "Pitt Shag (Phalacrocorax featherstoni) - BirdLife species factsheet". Birdlife.org. Retrieved 2015-08-27.

^ "Chatham Albatross (Thalassarche eremita) - BirdLife species factsheet". Birdlife.org. 2010-12-02. Retrieved 2015-08-27.

^ Rowe, S (August 2010). "Level 1 Risk Assessment for Incidental Seabird Mortality Associated with New Zealand Fisheries in the NZ-EEZ" (PDF).

^ "Seabirds Recorded at the Chatham Islands, 1960 to May 1993" (PDF). Notornis.osnz.org.nz. Retrieved 2015-08-27.

^ Jolly, Dyanna (2014). Cultural Impact Assessment Report (PDF). Chatham Rock Phosphate. p. 10. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 February 2016. Retrieved 14 March 2016.

^ McFadgen 1994

^ Clark 1994: 123–135.

^ Davis and Solomon 2006

^ Howe 2006

^ ab King 2000

^ Kerry R. Howe (2003). The Quest for Origins: Who First Discovered and Settled New Zealand and the Pacific Islands? Auckland:Penguin, page 182

^ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. 6 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 6–7.

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. 6 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 6–7.

^ ab King, M. (2004). Being Pakeha. Penguin. p 196.

^ Rekohu[full citation needed]

^ ab McNab, Robert (1913). "XIX. — American Whalers and Scientists, 1838 to 1840". The Old Whaling Days. Victoria University of Wellington. Retrieved 2 December 2018.

^ McNab, Robert (1913). "XV. — The French Fleet, 1836 to 1838". The Old Whaling Days. Victoria University of Wellington. Retrieved 3 December 2018.

^ Patricia Burns (1989). Fatal Success: A History of the New Zealand Company. Heinemann Reed. pp. 243, 244. ISBN 978-0-7900-0011-4.

^ Musket Wars. p354-356.R.Crosby. Reed. 1999

^ Rykers, Ellen (July–August 2018). "The lie of the land". New Zealand Geographic. 152: 92–103.

^ "German Missions". Reference Guides - Missionary Sources (PDF). Hocken Collections. 2008. p. 10. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 December 2008. Retrieved 9 December 2008.

^ ab Richards, Rhys (4 May 2015). "Chatham Islands – Since the 1980s". Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 5 January 2019.

^ Richards, Rhys (4 May 2015). "Chatham Islands – Chatham Islands from the 1860s to the 1980s". Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 5 January 2019.

^ [1] Archived 12 February 2005 at the Wayback Machine

^ Ngati Archived 23 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine

^ Richards, Rhys (4 May 2015). "Chatham Islands - Since the 1980s'". Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 28 February 2019.

^ abcdefg 2013 Census QuickStats about a place:Chatham Islands Territory

^ "1996 Census of Population and Dwellings – Census Night Population". Statistics New Zealand. 28 February 1997. Archived from the original on 13 February 2016. Retrieved 17 May 2016.

^ "Getting to the Chatham Island". Discoverthechathamislands.co.nz. Archived from the original on 25 September 2015. Retrieved 2015-08-27.

^ ab "Chatham Islands Shipping Ltd". Retrieved 2015-08-27.

^ www.seawings.co.uk, flying boat forum. "Short flying boats in New Zealand". Retrieved 3 June 2013.

^ Blakiston, Fergus (29 August 2015). "The good ship Rangatira". The Timaru Herald. Retrieved 28 October 2015.

^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 12 July 2012. Retrieved 13 January 2008.CS1 maint: Archived copy as title (link)

^ See http://www.cic.govt.nz/

^ "Your Council » Chatham Islands Council".

^ New Zealand Herald, 15 October 2010

^ New Zealand Gazette 14 August 2003

^ Stewart, Ashleigh (25 July 2015). "Ministry of Health 'concerned about financial performance' of CDHB". The Press.As of July 1, control of the Chatham Islands' health services will transfer to Canterbury.

^ See, for example, page 2 of the Chatham Islands Council 2015-2016 Annual Report, http://www.cic.govt.nz/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/Chatham_Islands_Annual_Report_2015-16_Web_Version.pdf

^ "Contact Us". Airchathams.co.nz. Archived from the original on 9 September 2015. Retrieved 27 August 2015.

^ "Chatham Islands Wind Farm". New Zealand Wind Energy Association. Retrieved 4 January 2017.

^ See the 2013-14 Chatham Islands Electricity Ltd Annual Report on page 6 of this document https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B1OcswQ6_z-OSmVwTDNBdGEycTA/edit

Bibliography

Clark, Ross. 1994. Moriori and Māori: The Linguistic Evidence. In Sutton, Douglas G., ed., The Origins of the First New Zealanders. Auckland: Auckland University Press.- Davis, Denise and Solomon, Māui. 2006. Moriori. In Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, updated 9 June 2006.

Diamond, Jared (1997). Guns, Germs, and Steel: The Fates of Human Societies. New York: W. W. Norton. p. 53.

- Howe, Kerry R. 2006. Ideas of Māori origins. In Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, updated 9 June 2006.

King, Michael (1989). Moriori: A People Rediscovered (2000 ed.). Viking. ISBN 978-0-14-010391-5.

McFadgen, B. G. (March 1994). "Archaeology and Holocene sand dune stratigraphy on Chatham Island". Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand. 24 (1): 17–44. doi:10.1080/03014223.1994.9517454.

Harper, Paul (15 October 2010). "Voter turnout up in local elections". The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 16 October 2010.

Waitangi Tribunal. 2001. Rekohu: A Report on Moriori and Ngati Mutunga Claims in the Chatham Islands. Report No. 64.

Film

The Wizard and the Commodore (2017), Director Samuel A. Miller, Narrator Davey Round

Further reading

New Zealand (2008). Chatham Islands: Heritage and Conservation (Rev. and enl. ed.). Christchurch, N.Z: Canterbury University Press in association with the Dept. of Conservation. ISBN 978-1-877257-78-0.

External links

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Chatham Islands. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Chatham Islands. |

- Chatham Islands Council

- 1998 Information

- Photographs from the Christchurch Public Library

- Department of Conservation information

- Unofficial Flag

- Massey University study of Chathams ecology

- Information and pictures of Chatham Islands. The Sisters are also mentioned

Pitt Island Education Resources.

Rekohu: The Chatham Islands Education Resources.

Administrative divisions of the Realm of New Zealand | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Countries | | | |||||||||

Regions | 11 non-unitary regions | 5 unitary regions | Chatham Islands | | Outlying islands outside any regional authority (the Kermadec Islands, Three Kings Islands, and Subantarctic Islands) | Ross Dependency | 15 islands | 14 villages | |||

Territorial authorities | 13 cities and 53 districts | ||||||||||

| Notes | Some districts lie in more than one region | These combine the regional and the territorial authority levels in one | Special territorial authority | The outlying Solander Islands form part of the Southland Region | New Zealand's Antarctic territory | Non-self-governing territory of New Zealand | States in free association with New Zealand | ||||