Tariff

| Taxation | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||

An aspect of fiscal policy | ||||||||

Policies

| ||||||||

Economics

| ||||||||

Collection

| ||||||||

Noncompliance

| ||||||||

Types

| ||||||||

International

| ||||||||

Trade

| ||||||||

Research

| ||||||||

Religious

| ||||||||

By country

| ||||||||

A tariff is a tax on imports or exports between sovereign states. It is a form of regulation of foreign trade. It is a policy that taxes foreign products to encourage or protect domestic industry. The tariff is historically used to protect infant industries and to allow import substitution industrialization.

Contents

1 History

1.1 19th century

1.1.1 Europe

1.1.1.1 European Great Depression

1.1.1.2 Return of protectionism

1.1.2 Third World

1.1.2.1 Colonies

1.1.2.2 Independent countries

1.2 20th century

1.2.1 Tariffs and the Great Depression

1.3 Protectionism and free trade among nations

1.3.1 Great Britain

1.3.2 United States

1.3.3 Russia

1.3.4 India

2 Arguments in favor of tariffs

2.1 Free trade and specialization

2.2 Free trade and economic impacts

2.2.1 Trade deficit and desindustrialisation

2.2.2 Wage deflation

2.2.3 Debt crisis

2.3 Foreign trade and economic growth

2.4 The winner is the one who doesn't play the game

2.5 Free trade and poverty

2.6 Keynes and trade balance

2.7 Protection of infant industry

2.8 Protection against dumping

2.9 Criticism of the theory of comparative advantage

2.9.1 International mobility of capital and labour

2.9.2 Externalities

2.9.3 Cross-industrial movement of productive resources

2.9.4 Static vs. dynamic gains via international trade

2.9.5 Balanced trade and adjustment mechanisms

2.9.6 International trade as bartering

2.9.7 Using labour and capital to their full potential

3 Etymology

4 Customs duty

4.1 Calculation of customs duty

4.2 Harmonized System of Nomenclature

4.3 Customs authority

4.4 Evasion

4.5 Duty-free goods

4.6 Duty calculation for companies in real life

5 Economic analysis

5.1 Optimum tariff

6 Political analysis

7 Within technology strategies

8 See also

8.1 Types

8.2 Trade dynamics

8.3 Trade liberalisation

9 References

10 Sources

11 Further reading

11.1 Books

11.2 Websites

12 External links

History

19th century

Average tariff rates for selected countries (1913–2007)

Tariff rates in Japan (1870–1960)

Average tariff rates in Spain and Italy (1860–1910)

Average tariff rates on manufactured products[1]

Average Levels of Duties (1875 and 1913) [1][2]

According to Paul Bairoch (Myths and Paradoxes of Economic History, 1994), the industrialized world of 1913 is similar to that of 1815: "An ocean of protectionism surrounding a few liberal islets", with the exception of a short free trade interlude in Europe between 1860 and 1892. Only two islands of liberalism emerged in the developed part: Great Britain and the Netherlands. On the other hand, "the Third World was an ocean of liberalism", with Western countries imposing so-called "unequal" treaties on colonized and even politically independent countries that required the lowering of customs barriers. Bairoch write that the "Third World" has in fact become underdeveloped because of the imposition of free trade while North America and Western Europe have been able to develop, precisely because they have rejected trade liberalism (free trade) in their history. He notes that:[1]

in history, free trade is the exception and protectionism the rule.

Europe

Trade liberalisation (free trade) in the United Kingdom from 1846 onwards was the first example of large-scale liberalisation after the Industrial Revolution and was initiated by the dominant economy. However, it is the only country where over a specific period (during the two decades from 1846), free trade coincided with an increase in growth. Bairoch explains this by the fact that the country had a significant lead over the other countries in 1846, given that the country had emerged from at least half a century of protectionism.[1] It was in 1860 that free trade made a real breakthrough in continental Europe with the Cobden-Chevalier Treaty signed by Napoleon III. The agreement was considered in France as a coup d'état, since the parliament was opposed to it, and the agreement was established by means of secret negotiations between Napoleon Ill's envoy Michel Chevalier (a follower of Saint-Simon) and Britain's Richard Cobden. That agreement was the first of a series which Britain would establish with several European countries, known as the "Cobden agreements": the Franco-Belgian treaty was signed in 1861 and between 1861 and 1866 almost all European countries joined the Cobden treaty. Only a few countries on the continent had adopted a truly liberal trade policy before 1860: the Netherlands, Denmark, Portugal, Switzerland, Sweden and Belgium. The decades that followed were not a period of growth and prosperity, but on the contrary they were likened to "the Great Depression".[1]

European Great Depression

Paul Bairoch notes in Myths and Paradoxes of Economic History that the Great European Depression began around 1870-1872 at the height of free trade in Europe between 1866 and 1877 and ended with the return to protectionism around 1892:[1]

The important point is not only that the crisis started at the height of free trade, but that it ended around 1892-1894, just as the return to protectionism became effective in continental Europe[...]It is almost certain that free trade coincided with the depression for which it was probably the cause, while protectionism was probably at the origin of growth and development in most of the current developed countrie.

In Europe, the slowdown in GNP growth was mainly the result of the decline in agricultural production growth; European tariff barriers were not completely eliminated on manufactured products, whereas they were totally eliminated on agricultural products in all countries.This agricultural crisis in continental Europe can be explained almost exclusively by the influx of foreign cereals, which became possible thanks to the abolition of tariff protection on cereals in continental Europe between 1866 and 1872. It was mainly the farmers who suffered because cheap imports led to the collapse of agricultural commodity prices; the farmers' standard of living fell or stagnated in almost all continental European countries. But it also affected overall demand for industrial goods and the construction sector. In France, which was an agrarian economy, wheat imports, which reached 0.3% of national production in 1851/1860, rose to 19% in 1888/1892. In Belgium, this percentage rose from 6% around 1850 to more than 100% around 1890.[1]

During the 1870s and 1880s, the United States was Europe's largest supplier of cereals. There was an increasing trade imbalance between Europe and the United States until the 1900s, given that the United States had higher tariffs. In the early 1860s, Europe and the United States pursued completely different trade policies. The 1860s were a period of growing protectionism in the United States, while the European free trade phase lasted from 1860 to 1892. The tariff average rate on imports of manufactured goods was in 1875 from 40% to 50% in the United States against 9% to 12% in continental Europe at the height of free trade.[1] It experienced a period of strong growth while Europe was in the midst of a depression. Around 1870, Europe's trade deficit with America represented 5% to 6% of the region's imports. It reached 32% in 1890 and 59% around 1900.

Return of protectionism

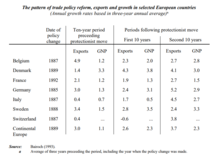

Trade Policy, Exports and Growth in European Countries

Germany was the first major European country to significantly change its trade policy by adopting a new tariff in July 1879. This new German tariff meant the end of the period of free trade on the continent. Thus, the period 1879-1892 saw the gradual return of protectionism in Europe and the period 1892-1914 can be described as that of growing protectionism in continental Europe, but not all countries changed their policies at the same pace.[1]

Bairoch also notes that it was when all countries were strengthening protectionism that the growth rate reached its highest level in continental Europe: indeed, GNP growth rose from 1.1%/year in the years 1850-1870 (protectionist period) to 0.2%/year in the years 1870-1890 (free trade period). And it was the countries that had returned to protectionism that mainly benefited from the economic recovery: during the protectionist phase (after 1892), GNP growth was 1.5% in Mainland Europe, while in the United Kingdom, which continued free trade, the rate reached about 0.7%. In all countries except Italy, and regardless of the date of policy review, the adoption of protectionist measures (after 1892) was followed by a sharp acceleration in growth in the first ten years; in the following decade, which is the decade of increased protection, there was a further acceleration in growth. In contrast, in the United Kingdom, where there was no change in free trade policy, there was an initial period of stagnation followed by a sharp decline in the growth rate. In 1892, France reintroduced strong protectionism: over the previous ten years, its GNP was 1.2%/year. In the first ten years after the protectionist change, GNP was 1.3%/year and the following decade it rose to 1.5%/year. The differences are even more marked in the case of Germany: after the introduction of new protectionist measures in 1885, GNP increased from 1.3% in the previous decade, to 3.1% in the following decade and to 2.9% in the second decade.[1]

Third World

From 1813 onwards, the economic liberalism (free trade) imposed by the Western powers on the Third World and the opening of these economies was one of the main causes of the lack of development. The import of large quantities of cheap manufactured goods led to a process of massive deindustrialization. Around 1750, the Third World produced about 70% to 76% of all manufactured goods in the world. But by 1913, it was only producing 7% to 8%. In 1913, the level of industrialization measured by the production of manufactured goods per capita was only one-third of its 1750 level.

Colonies

In India, for example, after the abolition in 1813 of the East India Company's trade monopoly, which prohibited the import of textile products into India, they quickly flowed into the country. While imports were either prohibited or subject to tariffs of 30% to 80% in Europe, British textile products entered the Indian market without paying any tariff. In 1813, India's textile industry was the country's leading industry as in any traditional society, and probably accounted for 45% to 65% of the country's total manufacturing activities. By the 1870s and 1880s, the rate of deindustrialization in this sector ranged from 55% to 75%. In the years 1890/1900 the rate of deindustrialization in metallurgy ranged from 95% to 99%. The process was similar or even more marked in the rest of Asia, with the exception of China where local industry survived better. In China, the deindustrialization of the textile industry ranged from 30% to 50%.[1]

Before independence, Latin American countries were under the domination of Spain and Portugal. The United Kingdom's intervention had greatly helped most of these countries to achieve political independence in the 19th century (mostly between 1804 and 1822). The United Kingdom was thus able to sign many trade treaties that opened the markets of these countries to British and European manufactured goods. The independence of most of these countries therefore paradoxically leads to a phase of deindustrialization because it facilitates the penetration of products from countries more advanced than Portugal and Spain. Thanks to the influence of North America, most Latin American countries changed their trade policies during the period 1870-1890 and imposed protective tariffs to support industrialization.[1]

Independent countries

With regard to independent third world countries or countries that did not have colony status in the 19th century (most of Latin America, China, Thailand, the entire Middle East), Western countries had exerted such pressure that most of them had signed treaties providing for the abolition of import duties. They were forced to open their markets to Western products, which allowed the massive entry of imported manufactured goods. Customs legislation could not provide for tariffs higher than 5% of the import value of the goods. Most of these "unequal treaties" were signed between 1810 and 1850, mainly at the initiative of the British.[1]

20th century

Tariffs and the Great Depression

The years 1920 to 1929 are generally misdescribed as years in which protectionism increased in Europe. In fact, from a general point of view, the crisis was preceded in Europe by trade liberalisation. The weighted average of tariffs remained tendentially the same as in the years preceding the First World War: 24.6% in 1913, as against 24.9% in 1927. In 1928 and 1929, tariffs were lowered in almost all developed countries. So there was no particular protectionism at the time.[3] In addition, the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act was signed by Hoover on June 17, 1930, while the Wall Street crash took place in the fall of 1929. Most of the trade contraction occurred between January 1930 and July 1932, before most protectionist measures were introduced (except for the limited measures applied by the United States in the summer of 1930). In the view of Maurice Allais, it was therefore the collapse of international liquidity that caused the contraction of trade, not customs tariffs.[4]Paul Bairoch therefore concludes that the argument that protectionism caused the 1929 crisis and the depression of the 1930s is a myth.[citation needed]

Most economists hold the opinion that the tariff act did not greatly worsen the great depression:

Milton Friedman held the opinion that the Smoot–Hawley tariff of 1930 did not cause the Great Depression, instead he blamed the lack of sufficient action on the part of the Federal Reserve. Douglas A. Irwin wrote: "most economists, both liberal and conservative, doubt that Smoot–Hawley played much of a role in the subsequent contraction".[5]

Peter Temin, an economist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, explained that a tariff is an expansionary policy, like a devaluation as it diverts demand from foreign to home producers. He noted that exports were 7 percent of GNP in 1929, they fell by 1.5 percent of 1929 GNP in the next two years and the fall was offset by the increase in domestic demand from tariff. He concluded that contrary the popular argument, contractionary effect of the tariff was small.[6]

William Bernstein wrote: "Between 1929 and 1932, real GDP fell 17 percent worldwide, and by 26 percent in the United States, but most economic historians now believe that only a miniscule part of that huge loss of both world GDP and the United States’ GDP can be ascribed to the tariff wars. .. At the time of Smoot-Hawley's passage, trade volume accounted for only about 9 percent of world economic output. Had all international trade been eliminated, and had no domestic use for the previously exported goods been found, world GDP would have fallen by the same amount — 9 percent. Between 1930 and 1933, worldwide trade volume fell off by one-third to one-half. Depending on how the falloff is measured, this computes to 3 to 5 percent of world GDP, and these losses were partially made up by more expensive domestic goods. Thus, the damage done could not possibly have exceeded 1 or 2 percent of world GDP — nowhere near the 17 percent falloff seen during the Great Depression... The inescapable conclusion: contrary to public perception, Smoot-Hawley did not cause, or even significantly deepen, the Great Depression.[7]

Protectionism and free trade among nations

Great Britain

Edward III (1312–1377) was the first king who deliberately tried to expand the wool cloth manufacture. He brought Flemish weavers, centralized the raw wool trade and banned the importation of wool fabrics.[8]

Using the tariffs, Tudor monarchs, particularly Henry VII (1485-1509), transformed England from a raw wool exporter into the world's largest wool manufacturing nation.[8]

At the beginning of the 19th century, Britain's average tariff on manufactured goods was roughly 51 percent, the highest of any major nation in Europe. And even after Britain embraced free trade in most goods, it continued to tightly regulate trade in strategic capital goods, such as the machinery for the mass production of textiles.[3] Thus seen, according to Bairoch, Britain's technological lead had been achieved "behind high and long-lasting tariff barriers".[1]

In 1800, Great Britain with about 10% of the European population, provided 29% of all pig iron produced in Europe, a proportion that reached 45% in 1830; industrial production per capita was even more significant: in 1830 it was 250% higher than in the rest of Europe compared to 110% in 1800. In 1846, the industrialization rate per capita was more than double that of its closest competitors such as France, Belgium, Germany, Switzerland and the United States.[1]

Tariffs were reduced in 1833 and the Corn Law was repealed in 1846, which amounted to free trade in food. (The Corn Laws were passed in 1815 to restrict wheat imports and guarantee British farmers' incomes ). This devastated Britain's old rural economy. Tariffs on many manufactured goods have also been abolished. But as free trade progressed in the United Kingdom, protectionism continued on the continent.[1]

British elites expected that thanks to free trade their lead in shipping, technology, scale economies and financial infrastructure to be self-reinforcing and thus last indefinitely. Britain practiced free trade unilaterally in the vain hope of imitation, but the United States emerged from the Civil War even more explicitly protectionist than before, Germany under Bismarck turned in this direction in 1879, and the rest of Europe followed. During the 1880s and 1890s, tariffs went up in Sweden, Italy, France, Austria-Hungary and Spain.[3]

Britain's economy still grew, but inexorably lagged: from 1870 to 1913, industrial production rose an average of 4.7 percent per year in the U.S., 4.1 percent in Germany, but only 2.1 percent in Britain. It was surpassed economically by the U.S. around 1880. Britain's lead in textiles and steelheld eroded as other nations caught up. Britain then fell behind as new industries, using more advanced technology, emerged after 1870 in states that still practiced protectionism.[3]

On 15 June 1903, the Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, [Henry Petty-Fitzmaurice, 5th Marquess of Lansdowne|the Marquess of Lansdowne]] made a speech in the House of Lords defending fiscal retaliation against countries with high tariffs and whose governments subsidised products for sale in Britain (known as 'bounty-fed products', also called dumping). The retaliation was to be done by threatening to impose tariffs in response against that country's goods. His Liberal Unionists had split from the Liberals, who promoted Free Trade, and the speech was a landmark in the group's slide towards Protectionism. Landsdowne argued that threatening retaliatory tariffs was similar to getting respect in a room of armed men by showing a big revolver (his exact words were "a rather larger revolver than everybody else's"). The "Big Revolver" became a catchphrase of the day, often used in speeches and cartoons[9]

Fundamentally, the country believed that free trade was optimal as a permanent policy and was satisfied with laissez faire absence of industrial policy. But contrary to British belief, free trade did not improve the economic situation and increased competition from foreign production eventually devastated Britain's old rural economy. Britain finally abandoned free trade in 1932 until 1950.[3]

United States

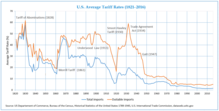

Average tariff rates (France, UK, US)

Average tariff rates in US (1821–2016)

US Trade Balance and Trade Policy (1895–2015)

Before the new Constitution took effect in 1788, the Congress could not levy taxes--it sold land or begged money from the states. The new national government needed revenue and decided to depend upon a tax on imports with the Tariff of 1789.[10] The policy of the U.S. before 1860 was low tariffs "for revenue only" (since duties continued to fund the national government).[11] A high tariff was attempted in 1828 but the South denounced it as a "Tariff of Abominations" and it almost caused a rebellion in South Carolina until it was lowered.[12] The policy from 1860 to 1933 was usually high protective tariffs (apart from 1913-21) After 1890, the tariff on wool did affect an important industry, but otherwise the tariffs were designed to keep American wages high. The conservative Republican tradition, typified by William McKinley was a high tariff, while the Democrats typically called for a lower tariff to help consumers.[13][14]

Protectionism was an American tradition: according to Paul Bairoch, the United States was "the homeland and bastion of modern protectionism" since the end of the 18th century and until after World War II.[15]

The intellectual leader of the high tariff movement was Alexander Hamilton, the first Secretary of the Treasury of the United States (1789-1795) and Daniel Raymond were the first theorists to present the infant industry argument, not the German economist Friedrich List.[8] Hamilton feared that Britain's policy towards the colonies would condemn the United States to be only producers of agricultural products and raw materials. Washington and Hamilton believed that political independence was predicated upon economic independence. Increasing the domestic supply of manufactured goods, particularly war materials, was seen as an issue of national security. Hamilton was the first to use the term "infant industries" and to introduce the infant industry argument to the forefront of economic thinking. In Report on Manufactures which is considered the first text to express modern protectionist theory, he called for customs barriers to allow American industrial development and to help protect infant industries, including bounties (subsidies) derived in part from those tariffs.[16] Hamilton explained that despite an initial “increase of price” caused by regulations that control foreign competition, once a “domestic manufacture has attained to perfection… it invariably becomes cheaper”. In Hamilton's day he was never able to obtain the high tariff he wanted.

The Tariff Act was the second bill of the Republic signed by President George Washington allowing Congress to impose a fixed tariff of 5% on all imports, with a few exceptions. The main purpose was to provide revenue to fund the national government.[3] In 1812, all tariffs were increased to 25% due to the war.[17] There was a brief episode of free trade from 1846 but the panic of 1857 eventually led to higher tariff demands than President James Buchanan, signed in 1861 (Morrill Tariff).[3]

In the 19th century, statesmen such as Senator Henry Clay continued Hamilton's themes within the Whig Party under the name "American System.[18] Before 1860 they were always defeated by the low-tariff Democrats.[19]

The American Civil War (1861-1865) allowed the industrial Northeast to get the high tariffs it wanted. The money was needed to finance the war and war debt, but for the next half-century high tariffs were a policy designed to encourage rapid industrialisation and protect the high American wage rates. The Democrats called for low tariffs help poor consumers, but they always failed until 1913. The Republican Party, which is heir to the Whigs, makes protectionism a central theme in its electoral platforms. According to the party, it is right to favour domestic producers and tax foreigners and consumers of imported luxury products. Republicans prioritize the protection function, while the need to provide revenue to the federal budget is only a secondary objective.

In the early 1860s, Europe and the United States pursued completely different trade policies. The 1860s were a period of growing protectionism in the United States, while the European free trade phase lasted from 1860 to 1892. The tariff average rate on imports of manufactured goods was in 1875 from 40% to 50% in the United States against 9% to 12% in continental Europe at the height of free trade. Between 1850 and 1870 the annual growth rate of GNP per capita was 1.8%, 2.1% between 1870 and 1890 and 2% between 1890 and 1910; the best twenty years of economic growth were therefore those of the most protectionist period (between 1870 and 1890), while European countries were following a free trade policy.[1]

After the United States overtook European industries in the 1890s, the argument for the Mckinley tariff was no longer to protect the "infant industry" but rather to maintain workers' wage levels, improve protection of the agricultural sector and the principle of reciprocity.[1]

Alfred Eckes Jr notes that from 1871 to 1913, the average U.S. tariff on dutiable imports never fell below 38 percent and gross national product (GNP) grew 4.3 percent annually, twice the pace in free trade Britain and well above the U.S. average in the 20th century (Opening America's Market: U.S. Foreign Trade Policy Since 1776, Alfred Eckes Jr). According to Ian Fletcher, the protectionist periode "was the golden age of American industry, when America’s economic performance surpassed the rest of the world by the greatest margin".[3]

Russia

Russia adopted more protectionist trade measures in 2013 than any other country, making it the world leader in protectionism. It alone introduced 20% of protectionist measures worldwide and one-third of measures in the G20 countries. Russia's protectionist policies include tariff measures, import restrictions, sanitary measures, direct subsidies to local companies. For example, the state supported several economic sectors such as agriculture, space, automotive, electronics, chemistry, energy and many others.[20][21]

From 2014, tariffs have been applied on imported products in the food sector. Import substitution in this sector, i.e. the replacement of imported products by domestic products, is considered a success since it has enabled Russia to increase domestic production and save several billion dollars. The value of food imports has decreased from $60 billion to $20 billion since 2014. In the fisheries sector, fruit and vegetables, domestic production increased sharply, imports decreased significantly and the trade balance (difference between exports and imports) improved. This has allowed Russia to be self-sufficient in agricultural products.[22][23][24]

India

From 2017, as part of the promotion of its "Make in India" programme[25] to stimulate and protect domestic manufacturing industry and to combat current account deficits, India has introduced tariffs on several electronic products and "non-essential items". This concerns items imported from countries such as China and South Korea. For example, India's national solar energy programme favours domestic producers by requiring the use of Indian-made solar cells.[26][27][28]

Arguments in favor of tariffs

Free trade and specialization

Erik Reinert points out that the specialization advocated by the theory of free trade does not promote economic development . in fact the most advanced economies are all based on the diversity of economic activities and it is the least developed countries that are the most specialized. Pre-Ricardian economists, such as Antonio Serra as early as 1613, had established that the richest cities are those where the diversity of professions is the highest. This creates synergy effects between the different sectors. [29]

In addition, Erik Reinert notes that free trade theorie do not distinguish between activities with increasing returns and activities with decreasing returns. It pretend that all activities are with decreasing returns and neglect the existence of activities that allow economies of scale. In reality, specializations are not equal and a country cannot sustainably increase its standard of living per capita without developing activities with increasing returns, i.e. activities whose productivity increases with production. This concerns manufacturing industry but also some services. Countries that specialized in activities with decreasing returns such as agriculture or natural resource extraction eventually became poorer. In these activities, sooner or later, an increase in the quantities produced will lead to an increase in the average cost due to land or reservoir depletion. So, for a country to create wealth, the best way is to develop its manufacturing sector and protect it. But this requires protective measures without which the industry will eventually be destroyed because of trade deficits.[29]

Free trade and economic impacts

Trade deficit and desindustrialisation

Bairoch observes that protectionism tends to promote industrialization, while free trade tends to destroy it:[1]"Protectionism has always coincided in time with industrialization and economic development and is even at the origin of it."

The Ottoman Empire served as an example to Disraeli, who disapproved of British free trade, particularly during the discussions on the abolition of the Corn Laws (February 1846):[1]"the system of pure competition and perfectly applied for a very long time [...], free trade was applied in Turkey and what did it produce? It detroyed some of the best manufactures in the world."

Wage deflation

U.S. Productivity, Real Hourly Compensation and Trade Policy (1948-2013)[30]

Some countries (for example in Asia) have developed very high currency devaluations and policies of social and ecological dumping. In the context of generalized free trade established by the WTO, this has led to a strong wage deflation effect in developed countries. Indeed, financial and trade liberalization has facilitated imbalances between production and consumption in developed countries, leading to crises. In all developed countries, the gap between average and median income is widening. For some countries, there is absolute stagnation, and even regression in the income of the majority of the population.[31] This wage deflation effect has been spread by the threat of relocations leading employees to accept more deteriorated social and wage conditions in order to preserve employment. Due to the pressure of low-cost production, in the free trade system, developed countries have only a choice between wage deflation or offshoring and unemployment.[32] Free trade is incompatible with high wages, as the worker would have no chance of resisting competition from low-wage foreign workers and from countries that practice monetary, social, environmental, fiscal dumping policies.

In the United States, the share of labour compensation in national income fell to 51.6% in 2006 - its lowest historical point since 1929 - from 54.9% in 2000.[33] For the period 2000-2007, the increase in the median real wage was only 0,1 %, while the median household income fell by 0,3 % per year in real terms. The reduction was greater for the poorest households. During the same period, the poorest 20% of the population saw their income fall by 0,7 % per year. Since 2000, the increase in hourly wages has not kept pace with productivity gains.[32] In the United States in 2011, competition with workers from low-wage countries facilitated by free trade reduced the wages of the 100 million American workers without university degrees by about $1,800 per year per full-time worker.

[34]

While the dumping policies of some countries have had a devastating effect on developed economies, they have also largely destabilized developing countries. Studies on the effects of free trade show that the gains induced by WTO rules for developing countries are very small. This has reduced the gain for these countries from an estimated $539 billion in the 2003 LINKAGE model to $22 billion in the 2005 GTAP model. The 2005 LINKAGE version also reduced gains to 90 billion. As for the "Doha Round", it would have brought in only $4 billion to developing countries (including China...) according to the GTAP model.[35] However, the models used are actually designed to maximize the positive effects of trade liberalization. They are characterized by the absence of taking into account the loss of income caused by the end of tariff barriers.[36] In fact, since the group of "developing" countries includes China and India, when the various effects of trade liberalization, not all of which are included in the GTAP or LINKAGE models, are taken into account, the balance is directly negative for the other countries, as the cumulative gain of China and India far exceeds the gain of the "developing" countries. Free trade has not been a factor in the development of the poorest countries.[32]

Debt crisis

The boom in credit mechanisms, which technically triggered the crisis, resulted from an attempt to maintain the consumption capacity of as many people as possible while incomes stagnated or even fell (as in the United States for the median household). Household debt is increasing dramatically in all developed countries. In the United States, for example, debt in ten years increased from 61% to 100% of GDP between 1997 and 2007. In Great Britain and Spain, it exceeds 100% of GDP (from 2007). Thus, household debt has increased in the last ten years from 33% of GDP to 45% in France and has reached 68% of GDP in Germany; moreover, the competitive pressure exerted by dumping policies has resulted in a rapid increase in corporate debt.[32] The increase in the indebtedness of private agents (households and businesses) in developed countries, at a time when the incomes of the majority of households were being driven down, relatively or absolutely, by the effects of wage deflation, could only lead to an insolvency crisis. This is what led to the financial crisis.[32]

The insolvency of the vast majority of households is at the centre of the mortgage debt crisis that has been experienced in the United States, the United Kingdom and Spain. However, this crisis in private agents' indebtedness is a direct result of the liberalization of international trade. At the heart of the crisis, therefore, are not the banks, whose disorders are only a symptom here, but free trade, whose effects have come to combine with those of liberalized finance.[32]

Thus, globalization has created imbalances, such as wage deflation in developed economies. These imbalances in turn led to sudden increases in the debt of private actors. And this led to an insolvency crisis. Finally, the crises follow one another more and more quickly, and they are more and more brutal. The establishment of protectionist measures such as quotas and tariffs is therefore the essential condition for protecting countries' domestic markets and increasing wages. This could allow the reconstruction of the internal market on a stable basis, with a significant improvement in the solvency of both households and businesses.[32]

Foreign trade and economic growth

According to Paul Bairoch, "it is economic growth that generates foreign trade, not the opposite". James Riedel, also comes to the same conclusion in his study entitled Trade as an engine of growth: Theory and Evidence and writes: "in reality, there is very little left of the assumptions that generated the mechanistic conclusions of trade theory as an engine of growth" [...]

"A thorough examination of the stylized facts that underline the theory of trade as an growth engine reveals that it is only a myth".[1] Domestic production is therefore more important for economic growth than foreign trade. Thus, promoting economic development requires protecting domestic production rather than sacrificing it (because of trade deficits) for the benefit of liberalization and expansion of foreign trade. Bairoch notes several examples:[1]

- During The Long Depression, the economic slowdown of nations preceded that of foreign trade. This indicates that it is national growth that drives foreign trade.

- During the 1929 Great Depression, it was the decline in the nations' domestic production that preceded the decline in foreign trade: at the world level, in 1930, the world's industrial production (minus Russia) fell by 14% while the volume of world trade fell by only 7%; In 1931, the figures were -13% for industry and -8% for world trade; in 1932 they were -15% for industry and -13% for world trade. In the United States, industrial production had declined since October 1929, while the value of all American exports rose by 20% and the value of manufactured goods exports rose by 5%.[1]

The winner is the one who doesn't play the game

The poor countries that have succeeded in achieving strong and sustainable growth are those that have become mercantilists, not free traders: China, South Korea, Japan, Taiwan...Thus, whereas in the 1990s, China and India had the same GDP per capita, China followed a much more mercantilist policy and now has a GDP per capita three times higher than India's.Indeed, a significant part of China's rise on the international trade scene does not come from the supposed benefits of international competition but from the relocations practiced by companies from developed countries. Dani Rodrik points out that it is the countries that have systematically violated the rules of globalisation that have experienced the strongest growth.[37] Bairoch notes that in the free trade system, "the winner is the one who does not play the game".[1]

For developed countries that have implemented free trade, the work of E.F. Denison on growth factors in the United States and Western Europe between 1950 and 1962 shows that the positive effects on growth of trade liberalization have been negligible in the United States, while in Western Europe it contributed to a weighted average of only 2% of total economic growth. J W W Kendrick whose work deals with GNP growth in the United States comes to the same conclusion.[1]

In 2003, the World Bank estimated the gains from the transition to WTO free trade rules for "developing" countries at only $539 billion (a small amount). In addition, the more recent GTAP 2005 model revised this estimate downward to only $4 billion. Knowing that all the gains are attributed to China and India, this means that, except for these two countries, the addition is very largely negative for all the other "developing" countries.[38]

Free trade and poverty

According to Paul Bairoch, a very large number of Third World countries that have followed free trade can now be considered as "quasi industrial deserts"; he notes that:

"Free trade meant for the Third World the acceleration of the process of economic underdevelopment[1]

.

Poor countries have become even poorer since they removed economic protections in the early 1980s. In 2003, 54 nations were poorer than they were in 1990 (UN Human Development Report 2003, p. 34).

During the 1960s and 1970s (protectionist period) the world economy grew much faster than between 1980 and 1999 (free trade period). World per capita income grew much faster in developed countries (3.2% /year between 1960 and 1980 compared to 2.2% /year between 1980 and 1999) and in developing countries (3% between 1960 and 1980 compared to 1.5%/year between 1980 and 1999). For example, it increased more rapidly in Latin America (3.1%/year between 1960 and 1980 compared to 0.6%/year between 1980 and 1999), the Middle East and North Africa (2.5%/year between 1960 and 1980 compared to -0.2% between 1980 and 1999)[39].

Sub-Saharan African countries have a lower per capita income in 2003 than 40 years earlier (Ndulu, World Bank, 2007, p. 33).[40] By practicing free trade, Africa is less industrialized today than it was four decades ago.

Free trade policies have caused economic depression in sub-Saharan Africa: per capita income increased by 37% between 1960 and 1980 and fell by 9% between 1980 and 2000. Africa's manufacturing sector's share of GDP decreased from 12% in 1980 to 11% in 2013. In the 1970s, Africa accounted for more than 3% of world manufacturing output, and now accounts for 1.5%.[41]

However, some African countries such as Ethiopia, and Rwanda have abandoned free trade and adopted a "developmental state model". They have succeeded in industrializing by regulating their economies and promoting their own manufacturing industries[42].

Keynes and trade balance

Trade deficits mean that consumers buy too much foreign goods and too few domestic products. According to Keynesian theory, trade deficits are harmful. Countries that import more than they export weaken their economies. As the trade deficit increases, unemployment or poverty increases and GDP slows down. And surplus countries getting richer at the expense of deficit countries. They destroy the production of their trading partners. John Maynard Keynes thought that surplus countries should be taxed to avoid trade imbalances.[43] The tariff is used to equalize the trade balance in order to protect domestic workers. Peter Temin explain that "a tariff is an expansionary policy, like a devaluation as it diverts demand from foreign to home producers".[44]

Keynes was the principal author of a proposal – the so-called Keynes Plan – for an International Clearing Union. The two governing principles of the plan were that the problem of settling outstanding balances should be solved by 'creating' additional 'international money', and that debtor and creditor should be treated almost alike as disturbers of equilibrium. The new system is not founded on free-trade (liberalisation[45] of foreign trade[46]) but rather on the regulation of international trade, in order to eliminate trade imbalances: the nations with a surplus would have an incentive to reduce it, and in doing so they would automatically clear other nations deficits.[47]

His view was supported by many economists and commentators at the time. In the words of Geoffrey Crowther, then editor of The Economist, "If the economic relationships between naticions are not, by one means or another, brought fairly close to balance, then there is no set of finanal arrangements that can rescue the world from the impoverishing results of chaos.".[48] Influenced by Keynes, economics texts in the immediate post-war period put a significant emphasis on balance in trade. For example, the second edition of the popular introductory textbook, An Outline of Money,[49] devoted the last three of its ten chapters to questions of foreign exchange management and in particular the 'problem of balance'. However, in more recent years, since the end of the Bretton Woods system in 1971, with the increasing influence of Monetarist schools of thought in the 1980s, and particularly in the face of large sustained trade imbalances, these concerns – and particularly concerns about the destabilising effects of large trade surpluses – have largely disappeared from mainstream economics discourse[50] and Keynes' insights have slipped from view.[51] They are receiving some attention again in the wake of the financial crisis of 2007–08.[52]

Protection of infant industry

In the 19th century, Alexander Hamilton and the economist Friedrich List defended the benefits of "educator protectionism" as a necessary means of protecting infant industries. Protectionism would be necessary in the short term for a country to start industrialization away from competition from more advanced foreign industries, under which pressure it could succumb at the first stage of the process. As a result, they benefit from greater freedom of manoeuvre and greater certainty regarding their profitability and future development. The protectionist phase is therefore a learning period that would allow the least developed countries to acquire general and technical know-how in the fields of industrial production in order to become competitive on international markets.

Protection against dumping

States resorting to protectionism invoke unfair competition or dumping practices:

- Monetary dumping: a currency undergoes a devaluation when monetary authorities decide to intervene in the foreign exchange market to lower the value of the currency against other currencies. This makes local products more competitive and imported products more expensive (Marshall Lerner Condition), increasing exports and decreasing imports, and thus improving the trade balance. Countries with a weak currency cause trade imbalances: they have large external surpluses while their competitors have large deficits.

- Tax Dumping: some tax haven states have lower corporate and personal tax rates.

- Social dumping: when a state reduces social contributions or maintains very low social standards (for example, in China, labour regulations are less restrictive for employers than elsewhere).

- Environmental dumping: when environmental regulations are less stringent than elsewhere.

Criticism of the theory of comparative advantage

Free trade is based on the theory of comparative advantage. The classical and neoclassical formulations of comparative advantage theory differ in the tools they use but share the same basis and logic. Comparative advantage theory says that market forces lead all factors of production to their best use in the economy. It indicates that international free trade would be beneficial for all participating countries as well as for the world as a whole because they could increase their overall production and consume more by specializing according to their comparative advantages. Goods would become cheaper and available in larger quantities. Moreover, this specialization would not be the result of chance or political intent, but would be automatic. However, the theory is based on assumptions that are neither theoretically nor empirically valid.[53]

International mobility of capital and labour

The international immobility of labour and capital is essential to the theory of comparative advantage. Without this, there would be no reason for international free trade to be regulated by comparative advantages. Classical and neoclassical economists all assume that labour and capital do not circulate between nations. At the international level, only the goods produced can move freely, with capital and labour trapped in countries. David Ricardo was aware that the international immobility of labour and capital is an indispensable hypothesis. He devoted half of his explanation of the theory to it in his book. He even explained that if labour and capital could move internationally, then comparative advantages could not determine international trade. Ricardo assumed that the reasons for the immobility of the capital would be:[53]

.mw-parser-output .templatequote{overflow:hidden;margin:1em 0;padding:0 40px}.mw-parser-output .templatequote .templatequotecite{line-height:1.5em;text-align:left;padding-left:1.6em;margin-top:0}

"the fancied or real insecurity of capital, when not under the immediate control of its owner, together with the natural disinclination which every man has to quit the country of his birth and connexions, and intrust himself with all his habits fixed, to a strange government and new laws"

Neoclassical economists, for their part, argue that the scale of these movements of workers and capital is negligible. They developed the theory of price compensation by factor that makes these movements superfluous.

In practice, however, workers move in large numbers from one country to another. Today, labour migration is truly a global phenomenon. And, with the reduction in transport and communication costs, capital has become increasingly mobile and frequently moves from one country to another. Moreover, the neoclassical assumption that factors are trapped at the national level has no theoretical basis and the assumption of factor price equalisation cannot justify international immobility. Moreover, there is no evidence that factor prices are equal worldwide. Comparative advantages cannot therefore determine the structure of international trade.[53]

If they are internationally mobile and the most productive use of factors is in another country, then free trade will lead them to migrate to that country. This will benefit the nation to which they emigrate, but not necessarily the others.

Externalities

An externality is the term used when the price of a product does not reflect its cost or real economic value. The classic negative externality is environmental degradation, which reduces the value of natural resources without increasing the price of the product that has caused them harm. The classic positive externality is technological encroachment, where one company's invention of a product allows others to copy or build on it, generating wealth that the original company cannot capture. If prices are wrong due to positive or negative externalities, free trade will produce sub-optimal results.[53]

For example, goods from a country with lax pollution standards will be too cheap. As a result, its trading partners will import too much. And the exporting country will export too much, concentrating its economy too much in industries that are not as profitable as they seem, ignoring the damage caused by pollution.

On the positive externalities, if an industry generates technological spinoffs for the rest of the economy, then free trade can let that industry be destroyed by foreign competition because the economy ignores its hidden value. Some industries generate new technologies, allow improvements in other industries and stimulate technological advances throughout the economy; losing these industries means losing all industries that would have resulted in the future.[53]

Cross-industrial movement of productive resources

Comparative advantage theory deals with the best use of resources and how to put the economy to its best use. But this implies that the resources used to manufacture one product can be used to produce another object. If they cannot, imports will not push the economy into industries better suited to its comparative advantage and will only destroy existing industries.[53]

For example, when workers cannot move from one industry to another—usually because they do not have the right skills or do not live in the right place—changes in the economy's comparative advantage will not shift them to a more appropriate industry, but rather to unemployment or precarious and unproductive jobs.[53]

Static vs. dynamic gains via international trade

Comparative advantage theory allows for a "static" and not a "dynamic" analysis of the economy. That is, it examines the facts at a single point in time and determines the best response to those facts at that point in time, given our productivity in various industries. But when it comes to long-term growth, it says nothing about how the facts can change tomorrow and how they can be changed in someone's favour. It does not indicate how best to transform factors of production into more productive factors in the future.[53]

According to theory, the only advantage of international trade is that goods become cheaper and available in larger quantities. Improving the static efficiency of existing resources would therefore be the only advantage of international trade. And the neoclassical formulation assumes that the factors of production are given only exogenously. Exogenous changes can come from population growth, industrial policies, the rate of capital accumulation (propensity for security) and technological inventions, among others. Dynamic developments endogenous to trade such as economic growth are not integrated into Ricardo's theory. And this is not affected by what is called "dynamic comparative advantage". In these models, comparative advantages develop and change over time, but this change is not the result of trade itself, but of a change in exogenous factors.[53]

However, the world, and in particular the industrialized countries, are characterized by dynamic gains endogenous to trade, such as technological growth that has led to an increase in the standard of living and wealth of the industrialized world. In addition, dynamic gains are more important than static gains.

Balanced trade and adjustment mechanisms

A crucial assumption in both the classical and neoclassical formulation of comparative advantage theory is that trade is balanced, which means that the value of imports is equal to the value of each country's exports. The volume of trade may change, but international trade will always be balanced at least after a certain adjustment period. The balance of trade is essential for theory because the resulting adjustment mechanism is responsible for transforming the comparative advantages of production costs into absolute price advantages. And this is necessary because it is the absolute price differences that determine the international flow of goods. Since consumers buy a good from the one who sells it cheapest, comparative advantages in terms of production costs must be transformed into absolute price advantages. In the case of floating exchange rates, it is the exchange rate adjustment mechanism that is responsible for this transformation of comparative advantages into absolute price advantages. In the case of fixed exchange rates, neoclassical theory suggests that trade is balanced by changes in wage rates.[53]

So if trade were not balanced in itself and if there were no adjustment mechanism, there would be no reason to achieve a comparative advantage. However, trade imbalances are the norm and balanced trade is in practice only an exception. In addition, financial crises such as the Asian crisis of the 1990s show that balance of payments imbalances are rarely benign and do not self-regulate. There is no adjustment mechanism in practice. Comparative advantages do not turn into price differences and therefore cannot explain international trade flows.[53]

Thus, theory can very easily recommend a trade policy that gives us the highest possible standard of living in the short term but none in the long term. This is what happens when a nation runs a trade deficit, which necessarily means that it goes into debt with foreigners or sells its existing assets to them. Thus, the nation applies a frenzy of consumption in the short term followed by a long-term decline.

International trade as bartering

The assumption that trade will always be balanced is a corollary of the fact that trade is understood as barter. The definition of international trade as barter trade is the basis for the assumption of balanced trade. Ricardo insists that international trade takes place as if it were purely a barter trade, a presumption that is maintained by subsequent classical and neoclassical economists. The quantity of money theory, which Ricardo uses, assumes that money is neutral and neglects the velocity of a currency. Money has only one function in international trade, namely as a means of exchange to facilitate trade.[53]

In practice, however, the velocity of circulation is not constant and the quantity of money is not neutral for the real economy. A capitalist world is not characterized by a barter economy but by a market economy. The main difference in the context of international trade is that sales and purchases no longer necessarily have to coincide. The seller is not necessarily obliged to buy immediately. Thus, money is not only a means of exchange. It is above all a means of payment and is also used to store value, settle debts and transfer wealth. Thus, unlike the barter hypothesis of the comparative advantage theory, money is not a commodity like any other. Rather, it is of practical importance to specifically own money rather than any commodity. And money as a store of value in a world of uncertainty has a significant influence on the motives and decisions of wealth holders and producers.[53]

Using labour and capital to their full potential

Ricardo and later classical economists assume that labour tends towards full employment and that capital is always fully used in a liberalized economy, because no capital owner will leave its capital unused but will always seek to make a profit from it. That there is no limit to the use of capital is a consequence of Jean-Baptiste Say's law, which presumes that production is limited only by resources and is also adopted by neoclassical economists.[53]

From a theoretical point of view, comparative advantage theory must assume that labour or capital is used to its full potential and that resources limit production. There are two reasons for this: the realization of gains through international trade and the adjustment mechanism. In addition, this assumption is necessary for the concept of opportunity costs. If unemployment (or underutilized resources) exists, there are no opportunity costs, because the production of one good can be increased without reducing the production of another good. Since comparative advantages are determined by opportunity costs in the neoclassical formulation, these cannot be calculated and this formulation would lose its logical basis.[53]

If a country's resources were not fully utilized, production and consumption could be increased at the national level without participating in international trade. The whole raison d'être of international trade would disappear, as would the possible gains. In this case, a State could even earn more by refraining from participating in international trade and stimulating domestic production, as this would allow it to employ more labour and capital and increase national income. Moreover, any adjustment mechanism underlying the theory no longer works if unemployment exists.[53]

In practice, however, the world is characterised by unemployment. Unemployment and underemployment of capital and labour are not a short-term phenomenon, but it is common and widespread. Unemployment and untapped resources are more the rule than the exception.

Etymology

The small Spanish town of Tarifa is sometimes credited with being the origin of the word "tariff", since it was the first port in history to charge merchants for the use of its docks.[54] The name "Tarifa" itself is derived from the name of the Berber warrior, Tarif ibn Malik. However, other sources assume that the origin of tariff is the Italian word tariffa translated as "list of prices, book of rates", which is derived from the Arabic ta'rif meaning "making known" or "to define".[55]

Customs duty

A customs duty or due is the indirect tax levied on the import or export of goods in international trade. In economic sense, a duty is also a kind of consumption tax. A duty levied on goods being imported is referred to as an import duty. Similarly, a duty levied on exports is called an export duty. A tariff, which is actually a list of commodities along with the leviable rate (amount) of customs duty, is popularly referred to as a customs duty.

Calculation of customs duty

Customs duty is calculated on the determination of the assessable value in case of those items for which the duty is levied ad valorem. This is often the transaction value unless a customs officer determines assessable value in accordance with the Harmonized System. For certain items like petroleum and alcohol, customs duty is realized at a specific rate applied to the volume of the import or export consignments.

Harmonized System of Nomenclature

For the purpose of assessment of customs duty, products are given an identification code that has come to be known as the Harmonized System code. This code was developed by the World Customs Organization based in Brussels. A Harmonized System code may be from four to ten digits. For example, 17.03 is the HS code for molasses from the extraction or refining of sugar. However, within 17.03, the number 17.03.90 stands for "Molasses (Excluding Cane Molasses)".

Introduction of Harmonized System code in 1990s has largely replaced the Standard International Trade Classification (SITC), though SITC remains in use for statistical purposes. In drawing up the national tariff, the revenue departments often specifies the rate of customs duty with reference to the HS code of the product. In some countries and customs unions, 6-digit HS codes are locally extended to 8 digits or 10 digits for further tariff discrimination: for example the European Union uses its 8-digit CN (Combined Nomenclature) and 10-digit TARIC codes.

Customs authority

A Customs authority in each country is responsible for collecting taxes on the import into or export of goods out of the country. Normally the Customs authority, operating under national law, is authorized to examine cargo in order to ascertain actual description, specification volume or quantity, so that the assessable value and the rate of duty may be correctly determined and applied.

Evasion

Evasion of customs duties takes place mainly in two ways. In one, the trader under-declares the value so that the assessable value is lower than actual. In a similar vein, a trader can evade customs duty by understatement of quantity or volume of the product of trade. A trader may also evade duty by misrepresenting traded goods, categorizing goods as items which attract lower customs duties. The evasion of customs duty may take place with or without the collaboration of customs officials. Evasion of customs duty does not necessarily constitute smuggling.[citation needed]

Duty-free goods

Many countries allow a traveler to bring goods into the country duty-free. These goods may be bought at ports and airports or sometimes within one country without attracting the usual government taxes and then brought into another country duty-free. Some countries impose allowances which limit the number or value of duty-free items that one person can bring into the country. These restrictions often apply to tobacco, wine, spirits, cosmetics, gifts and souvenirs. Often foreign diplomats and UN officials are entitled to duty-free goods. Duty-free goods are imported and stocked in what is called a bonded warehouse.

Duty calculation for companies in real life

With many methods and regulations, businesses at times struggle to manage the duties. In addition to difficulties in calculations, there are challenges in analyzing duties; and to opt for duty free options like using a bonded warehouse.

Companies use ERP software to calculate duties automatically to, on one hand, avoid error-prone manual work on duty regulations and formulas and on the other hand, manage and analyze the historically paid duties. Moreover, ERP software offers an option for customs warehouse, introduced to save duty and VAT payments. In addition, the duty deferment and suspension is also taken into consideration.

Economic analysis

Effects of import tariff, which hurts domestic consumers more than domestic producers are helped. Higher prices and lower quantities reduce consumer surplus by areas A+B+C+D, while expanding producer surplus by A and government revenue by C. Areas B and D are dead-weight losses, surplus lost by consumers and overall.[56]

Shows the consumer surplus, producer surplus, government revenue, and deadweight losses after tariff imposition.

General government revenue, in % of GDP, from import taxes. For this data, the variance of GDP per capita with purchasing power parity (PPP) is explained in 38 % by tax revenue.

Neoclassical economic theorists tend to view tariffs as distortions to the free market. Typical analyses find that tariffs tend to benefit domestic producers and government at the expense of consumers, and that the net welfare effects of a tariff on the importing country are negative. Normative judgments often follow from these findings, namely that it may be disadvantageous for a country to artificially shield an industry from world markets and that it might be better to allow a collapse to take place. Opposition to all tariff aims to reduce tariffs and to avoid countries discriminating between differing countries when applying tariffs. The diagrams at right show the costs and benefits of imposing a tariff on a good in the domestic economy.[56]

Imposing an import tariff has the following effects, shown in the first diagram in a hypothetical domestic market for televisions:

- Price rises from world price Pw to higher tariff price Pt.

- Quantity demanded by domestic consumers falls from C1 to C2, a movement along the demand curve due to higher price.

- Domestic suppliers are willing to supply Q2 rather than Q1, a movement along the supply curve due to the higher price, so the quantity imported falls from C1-Q1 to C2-Q2.

Consumer surplus (the area under the demand curve but above price) shrinks by areas A+B+C+D, as domestic consumers face higher prices and consume lower quantities.

Producer surplus (the area above the supply curve but below price) increases by area A, as domestic producers shielded from international competition can sell more of their product at a higher price.- Government tax revenue is the import quantity (C2-Q2) times the tariff price (Pw - Pt), shown as area C.

- Areas B and D are deadweight losses, surplus formerly captured by consumers that now is lost to all parties.

The overall change in welfare = Change in Consumer Surplus + Change in Producer Surplus + Change in Government Revenue = (-A-B-C-D) + A + C = -B-D. The final state after imposition of the tariff is indicated in the second diagram, with overall welfare reduced by the areas labeled "societal losses", which correspond to areas B and D in the first diagram. The losses to domestic consumers are greater than the combined benefits to domestic producers and government.[56]

Besides that above analysis is by a partial equilibrium analysis, however by a general equilibrium analysis, it showed that the income transfer caused among to the welfare concerned to the production of the good imposed tariff from the another welfare of production.[57]

That tariffs overall reduce welfare is not a controversial topic among economists. For example, the University of Chicago surveyed about 40 leading economists in March 2018 asking whether "Imposing new U.S. tariffs on steel and aluminum will improve Americans'welfare." About two-thirds strongly disagreed with the statement, while one third disagreed. None agreed or strongly agreed. Several commented that such tariffs would help a few Americans at the expense of many.[58] This is consistent with the explanation provided above, which is that losses to domestic consumers outweigh gains to domestic producers and government, by the amount of deadweight losses.[59]

Tariffs are more inefficient than consumption taxes.[60]

Optimum tariff

For economic efficiency, free trade is often the best policy, however levying a tariff is sometimes second best.

A tariff is called an optimal tariff if it's set to maximize the welfare of the country imposing the tariff.[61] It is a tariff derived by the intersection between the trade indifference curve of that country and the offer curve of another country. In this case, the welfare of the other country grows worse simultaneously, thus the policy is a kind of beggar thy neighbor policy. If the offer curve of the other country is a line through the origin point, the original country is in the condition of a small country, so any tariff worsens the welfare of the original country.[62][63]

It is possible to levy a tariff as a political policy choice, and to consider a theoretical optimum tariff rate.[64] When countries impose tariffs on each other, they will reach a position on the contract curve, which indicates a combination of trade quantities that satisfy each other's maximum welfare, with the countries trade own goods between each other.[65]

Political analysis

The tariff has been used as a political tool to establish an independent nation; for example, the United States Tariff Act of 1789, signed specifically on July 4, was called the "Second Declaration of Independence" by newspapers because it was intended to be the economic means to achieve the political goal of a sovereign and independent United States.[66]

The political impact of tariffs is judged depending on the political perspective; for example the 2002 United States steel tariff imposed a 30% tariff on a variety of imported steel products for a period of three years and American steel producers supported the tariff.[67]

Tariffs can emerge as a political issue prior to an election. In the leadup to the 2007 Australian Federal election, the Australian Labor Party announced it would undertake a review of Australian car tariffs if elected.[68] The Liberal Party made a similar commitment, while independent candidate Nick Xenophon announced his intention to introduce tariff-based legislation as "a matter of urgency".[69]

Unpopular tariffs are known to have ignited social unrest, for example the 1905 meat riots in Chile that developed in protest against tariffs applied to the cattle imports from Argentina.[70][71]

Within technology strategies

When tariffs are an integral element of a country's technology strategy, some economists believe that such tariffs can be highly effective in helping to increase and maintain the country's economic health. Other economists might be less enthusiastic, as tariffs may reduce trade and there may be many spillovers and externalities involved with trade and tariffs. The existence of these externalities makes the imposition of tariffs a rather ambiguous strategy. As an integral part of the technology strategy, tariffs are effective in supporting the technology strategy's function of enabling the country to outmaneuver the competition in the acquisition and utilization of technology in order to produce products and provide services that excel at satisfying the customer needs for a competitive advantage in domestic and foreign markets. The notion that government and policy would be effective at finding new and infant technologies, rather than supporting existing politically motivated industry, rather than, say, international technology venture specialists, is however, unproven.

This is related to the infant industry argument.

In contrast, in economic theory tariffs are viewed as a primary element in international trade with the function of the tariff being to influence the flow of trade by lowering or raising the price of targeted goods to create what amounts to an artificial competitive advantage. When tariffs are viewed and used in this fashion, they are addressing the country's and the competitors' respective economic healths in terms of maximizing or minimizing revenue flow rather than in terms of the ability to generate and maintain a competitive advantage which is the source of the revenue. As a result, the impact of the tariffs on the economic health of the country are at best minimal but often are counter-productive.

A program within the US intelligence community, Project Socrates, that was tasked with addressing America's declining economic competitiveness, determined that countries like China and India were using tariffs as an integral element of their respective technology strategies to rapidly build their countries into economic superpowers. However, the US intelligence community tends to have limited inputs into developing US trade policy. It was also determined that the US, in its early years, had also used tariffs as an integral part of what amounted to technology strategies to transform the country into a superpower.[72]

See also

- Embargo

- Protectionism

- Trade barrier

- Non-tariff barriers to trade

Types

- Ad valorem tax

- Bound tariff rate

- Environmental tariff

- Import quota

- List of tariffs

- Tariff-rate quota

- Telecommunications tariff

- Electricity tariff

Trade dynamics

- Effective rate of protection

- Tariffication

Trade liberalisation

General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT)- International free trade agreement

- Swiss Formula

- United States International Trade Commission

References

^ abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz Bairoch, Paul (1993). Economics and world history : myths and paradoxes. Chicago: University of Chicago Press (published 1995). ISBN 0226034623. OCLC 27726126..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ Burke, Susan; Bairoch, Paul (June 1989). "Chapter I - European trade policy, 1815–1914". In Mathias, Peter; Pollard, Sidney. The Industrial Economies: The Development of Economic and Social Policies. The Cambridge Economic History of Europe from the Decline of the Roman Empire. Volume 8. New York: Cambridge University Press. pp. 1–160. doi:10.1017/chol9780521225045.002. ISBN 978-0521225045.

^ abcdefgh Fletcher, Ian (12 September 2010). "America Was Founded as a Protectionist Nation".

^ Maurice Allais (December 5–11, 2009). "Lettre aux français : contre les tabous indiscutés" (pdf). Marianne (in French). p. 38.

^ Irwin, Douglas A. (2011). Peddling Protectionism: Smoot-Hawley and the Great Depression. p. 116. ISBN 9781400888429.

^ Temin, P. (1989). Lessons from the Great Depression. MIT Press. ISBN 9780262261197.

^ William Bernstein. A Splendid Exchange: How Trade Shaped the World. p. 116.

^ abc "Kicking Away the Ladder: The "Real" History of Free Trade - FPIF". 30 December 2003.

^ Hugh Montgomery; Philip George Cambray (1906). A Dictionary of Political Phrases and Allusions: With a Short Bibliography. p. 33.

^ John C. Miller, The Federalist Era: 1789-1801 (1960), pp 14-15,

^ Percy Ashley, "Modern Tariff History: Germany, United States, France (3rd ed. 1920) pp 133-265.

^ Robert V. Remini, "Martin Van Buren and the Tariff of Abominations." American Historical Review 63.4 (1958): 903-917.

^ F.W. Taussig,. The Tariff History of the United States. 8th edition (1931); 5th edition 1910 is online

^ Robert W. Merry, President McKinley: Architect of the American Century (2017) pp 70-83.

^ Chang, Ha-Joon; Gershman, John. "Kicking Away the Ladder: The "Real" History of Free Trade". ips-dc.org. Institute for Policy Studies. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

^ Morrison, Spencer P. (December 23, 2016). "America's Protectionist Past: The Hidden History Of Trade". National Economics Editorial. Retrieved December 30, 2016.

^ Morrison, Spencer P. (December 23, 2016). "America's Protectionist Past: The Hidden History Of Trade". National Economics Editorial. Retrieved January 4, 2017.

^ R. Luthin (1944). Abraham Lincoln and the Tariff.

^ William K. Bolt, Tariff Wars and the Politics of Jacksonian America (2017) covers 1816 to 1861.

^ https://themoscowtimes.com/articles/russia-leads-the-world-in-protectionist-trade-measures-study-says-30882

^ https://www.reuters.com/article/us-trade-protectionism/russia-was-most-protectionist-nation-in-2013-study-idUSBRE9BT0GP20131230

^ "Study: Russia Insulated From Further Sanctions by Import Substitution Success". 26 July 2017. Retrieved 15 March 2018.

^ Samofalova, Olga (10 February 2017). "Food import substitution turns out to be extremely profitable". Retrieved 15 March 2018.

^ https://www.independent.ie/business/farming/agri-business/record-breaking-food-production-in-russia-could-see-exports-reaching-40-billion-36700225.html

^ http://www.makeinindia.com/home

^ https://www.indiainfoline.com/article/news-top-story/import-duty-hike-on-consumer-durables-%E2%80%98make-in-india%E2%80%99-drive-to%20-get-a-boost-117121900244_1.html

^ https://www.reuters.com/article/us-india-textiles/india-doubles-import-tax-on-textile-products-may-hit-china-idUSKBN1KS17F

^ https://www.reuters.com/article/us-india-import-tax/india-to-raise-import-tariffs-on-electronic-and-communication-items-idUSKCN1ML2QB

^ ab Erik S. Reinert. How Rich Countries Got Rich… and Why Poor Countries Stay Poor.

^ Ravikumar, B.; Shao, Lin. "Labor Compensation and Labor Productivity: Recent Recoveries and the Long-Term Trend". Retrieved 15 March 2018.

^ https://www.ifs.org.uk/comms/comm101.pdf

^ abcdefg https://www.monde-diplomatique.fr/2009/03/SAPIR/16882

^ https://www.cbpp.org/research/share-of-national-income-going-to-wages-and-salaries-at-record-low-in-2006