Beaux-Arts architecture

The École des Beaux-Arts in Paris by François Debret (1819–32) then Félix Duban (1832–70), which gave its name to the Beaux-Arts architectural style

Beaux-arts buildings of University of California at Berkeley by John Galen Howard (1900–1911)

Beaux-Arts architecture (/ˌboʊˈzɑːr/; French: [bozaʁ]) was the academic architectural style taught at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, particularly from the 1830s to the end of the 19th century. It drew upon the principles of French neoclassicism, but also incorporated Gothic and Renaissance elements, and used modern materials, such as iron and glass. It was an important style in France until the end of the 19th century. It also had a strong influence on architecture in the United States, because of the many prominent American architects who studied at the Beaux-Arts, including Henry Hobson Richardson, John Galen Howard, Daniel Burnham, and Louis Sullivan.[1]

Contents

1 History

2 Training

3 Characteristics

4 Beaux-Arts architecture by country

4.1 France

4.2 United States

4.2.1 Architects

4.3 Canada

4.3.1 Buildings

4.3.2 Architects

4.4 Argentina

4.4.1 Buildings

4.4.2 Architects

4.5 Australia

4.6 Hong Kong

4.7 Philippines

5 See also

6 References

7 Bibliography

8 Further reading

9 External links

History

The "Beaux Arts" style evolved from the French classicism of the Style Louis XIV , and then French neoclassicism beginning with Louis XV and Louis XVI. French architectural styles before the French Revolution were governed by Académie royale d'architecture (1671–1793), then, following the French Revolution, by the Architecture section of the Académie des Beaux-Arts. The Academy held the competition for the "Grand Prix de Rome" in architecture, which offered prize winners a chance to study the classical architecture of antiquity in Rome.[2]

The formal neoclassicism of the old regime was challenged by four teachers at the Academy, Joseph-Louis Duc, Félix Duban, Henri Labrouste and Léon Vaudoyer, who had studied at the French Academy in Rome at the end of the 1820s, They wanted to break away from the strict formality of the old style by introducing new models of architecture from the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. Their goal was to create an authentic French style based on French models. Their work was aided beginning in 1837 by the creation of the Commission of Historic Monuments, headed by the writer and historian Prosper Mérimée, and by the great interest in the Middle Ages caused by the publication in 1831 of The Hunchback of Notre-Dame by Victor Hugo.

Their declared intention was to "imprint upon our architecture a truly national character."[1]

The style referred to as Beaux-Arts in English reached the apex of its development during the Second Empire (1852–1870)

and the Third Republic that followed. The style of instruction that produced Beaux-Arts architecture continued without major interruption until 1968.[2]

The Beaux-Arts style heavily influenced the architecture of the United States in the period from 1880 to 1920.[3] In contrast, many European architects of the period 1860–1914 outside France gravitated away from Beaux-Arts and towards their own national academic centers. Owing to the cultural politics of the late 19th century, British architects of Imperial classicism followed a somewhat more independent course, a development culminating in Sir Edwin Lutyens's New Delhi government buildings.[citation needed]

Training

The Beaux-Arts training emphasized the mainstream examples of Imperial Roman architecture between Augustus and the Severan emperors, Italian Renaissance, and French and Italian Baroque models especially, but the training could then be applied to a broader range of models: Quattrocento Florentine palace fronts or French late Gothic. American architects of the Beaux-Arts generation often returned to Greek models, which had a strong local history in the American Greek Revival of the early 19th century. For the first time, repertories of photographs supplemented meticulous scale drawings and on-site renderings of details.

Beaux-Arts training made great use of agrafes, clasps that link one architectural detail to another; to interpenetration of forms, a Baroque habit; to "speaking architecture" (architecture parlante) in which supposed appropriateness of symbolism could be taken to literal-minded extremes.

Beaux-Arts training emphasized the production of quick conceptual sketches, highly finished perspective presentation drawings, close attention to the program, and knowledgeable detailing. Site considerations tended toward social and urbane contexts.[4]

All architects-in-training passed through the obligatory stages—studying antique models, constructing analos, analyses reproducing Greek or Roman models, "pocket" studies and other conventional steps—in the long competition for the few desirable places at the Académie de France à Rome (housed in the Villa Medici) with traditional requirements of sending at intervals the presentation drawings called envois de Rome.

Characteristics

Beaux-Arts building decoration presenting images of the Roman goddesses Pomona and Diana. Note the naturalism of the postures and the channeled rustication of the stonework.

Alternating male and female mascarons decorate keystones on the San Francisco City Hall

Beaux-Arts architecture depended on sculptural decoration along conservative modern lines, employing French and Italian Baroque and Rococo formulas combined with an impressionistic finish and realism. In the façade shown above, Diana grasps the cornice she sits on in a natural action typical of Beaux-Arts integration of sculpture with architecture.

Slightly overscaled details, bold sculptural supporting consoles, rich deep cornices, swags and sculptural enrichments in the most bravura finish the client could afford gave employment to several generations of architectural modellers and carvers of Italian and Central European backgrounds. A sense of appropriate idiom at the craftsman level supported the design teams of the first truly modern architectural offices.

Characteristics of Beaux-Arts architecture included:

- Flat roof[3]

Rusticated and raised first story[3]

- Hierarchy of spaces, from "noble spaces"—grand entrances and staircases—to utilitarian ones

- Arched windows[3]

- Arched and pedimented doors[3]

- Classical details:[3] references to a synthesis of historicist styles and a tendency to eclecticism; fluently in a number of "manners"

- Symmetry[3]

- Statuary,[3] sculpture (bas-relief panels, figural sculptures, sculptural groups), murals, mosaics, and other artwork, all coordinated in theme to assert the identity of the building

- Classical architectural details:[3]balustrades, pilasters, garlands, cartouches, acroteria, with a prominent display of richly detailed clasps (agrafes), brackets and supporting consoles

- Subtle polychromy

Beaux-Arts architecture by country

France

The Conservatoire national des arts et métiers by Léon Vaudoyer (1838–67)

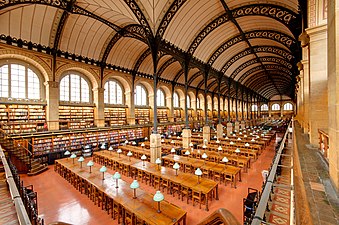

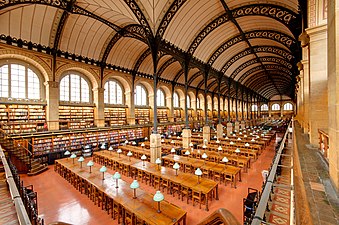

The Sainte-Geneviève Library by Henri Labrouste (1844–50)

Interior of the Sainte-Geneviève Library by Henri Labrouste (1844–50)

Museum of Natural History, Paris by Louis-Jules André (1877-1889)

The Grand Palais. Paris (1897-1900)

The Beaux-Arts style in France in the 19th century was initiated by four young architects trained at the École des Beaux-Arts, architects; Joseph-Louis Duc, Félix Duban, Henri Labrouste and Léon Vaudoyer, who had first studied Roman and Greek architecture at the Villa Medici in Rome, then in the 1820s began the systematic study of other historic architectural styles; including French architecture of the Middle Ages and Renaissance. They instituted teaching about a variety of architectural styles at the École des Beaux-Arts, and installed fragments of Renaissance and Medieval buildings in the courtyard of the school so students could draw and copy them. Each of them also designed new non-classical buildings in Paris inspired by a variety of different historic styles; Labrouste built the Sainte-Geneviève Library (1844–50); Duc designed the new Palais de Justice and Court of Cassation on the Île-de-la-Cité (1852–68); and Vaudroyer designed the Conservatoire national des arts et métiers (1838–67), and Duban designed the new buildings of the École des Beaux-Arts. Together, these buildings, drawing upon Renaissance, Gothic and romanesque and other non-classical styles, broke the monopoly of neoclassical architecture in Paris. [5]

United States

Facade of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, by Richard Morris Hunt (1902)

Grand Central Terminal (1913), New York City

Low Memorial Library at Columbia University by Charles Follen McKim (1895)

The San Francisco War Memorial Opera House by Arthur Brown Jr. (1932)

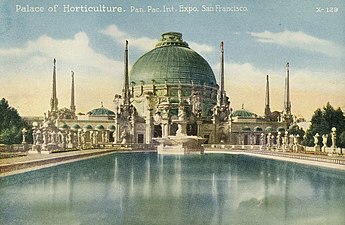

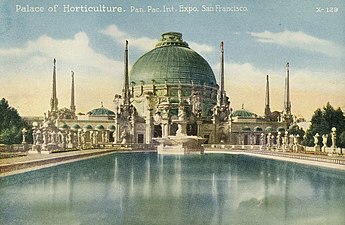

The Palace of Horticulture from the Panama–Pacific International Exposition in San Francisco by Arthur Brown Jr. (1915 demolished in 1916)

The first American architect to attend the École des Beaux-Arts was Richard Morris Hunt, between 1846 and 1855, followed by Henry Hobson Richardson in 1860. They were followed by an entire generation. Henry Hobson Richardson absorbed Beaux-Arts lessons in massing and spatial planning, then applied them to Romanesque architectural models that were not characteristic of the Beaux-Arts repertory. His Beaux-Arts training taught him to transcend slavish copying and recreate in the essential fully digested and idiomatic manner of his models. Richardson evolved a highly personal style (Richardsonian Romanesque) freed of historicism that was influential in early Modernism.[6]

The "White City" of the World's Columbian Exposition of 1893 in Chicago was a triumph of the movement and a major impetus for the short-lived City Beautiful movement in the United States.[7] Beaux-Arts city planning, with its Baroque insistence on vistas punctuated by symmetry, eye-catching monuments, axial avenues, uniform cornice heights, a harmonious "ensemble," and a somewhat theatrical nobility and accessible charm, embraced ideals that the ensuing Modernist movement decried or just dismissed.[8] The first American university to institute a Beaux-Arts curriculum is the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in 1893, when the French architect Constant-Désiré Despradelle was brought to MIT to teach. The Beaux-Arts curriculum was subsequently begun at Columbia University, the University of Pennsylvania, and elsewhere.[9] From 1916, the Beaux-Arts Institute of Design in New York City schooled architects, painters, and sculptors to work as active collaborators.

Numerous American university campuses were designed in the Beaux-Arts, notably: Columbia University, (commissioned in 1896), designed by McKim, Mead & White; the University of California, Berkeley (commissioned in 1898), designed by John Galen Howard; the United States Naval Academy (built 1901–1908), designed by Ernest Flagg; the campus of MIT (commissioned in 1913), designed by William W. Bosworth, Carnegie Mellon University (commissioned in 1904), designed by Henry Hornbostel; and the University of Texas (commissioned in 1931), designed by Paul Philippe Cret.

While the style of Beaux-Art buildings was adapted from historical models, the construction used the most modern available technology. The Grand Palais in Paris (1897–1900) had a modern iron frame inside; the classical columns were purely for decoration. The 1914–1916 construction of the Carolands Chateau south of San Francisco was built to withstand earthquakes, following the devastating 1906 San Francisco earthquake). The noted Spanish structural engineer Rafael Guastavino (1842–1908), famous for his vaultings, known as Guastavino tile work, designed vaults in dozens of Beaux-Arts buildings in the Boston, New York, and elsewhere. Beaux-Arts architecture also brought a civic face to the railroad. (Chicago's Union Station, Detroit's Michigan Central Station, Jacksonville's Union Terminal and Washington, DC's Union Station are famous American examples of this style.) Cincinnati has a number of notable Beaux-Arts style buildings, including the Hamilton County Memorial Building in the Over-the-Rhine neighborhood, and the former East End Carnegie library in the Columbia-Tusculum neighborhood. An ecclesiastical variant on the Beaux-Arts style is Minneapolis' Basilica of St. Mary,[10] the first basilica in the United States, which was designed by Franco-American architect Emmanuel Louis Masqueray (1861–1917) and opened in 1914. Two of the best American examples of the Beaux-Arts tradition stand within a few blocks of each other: Grand Central Terminal and the New York Public Library. Another prominent U.S. example of the style is the largest academic dormitory in the world, Bancroft Hall at the abovementioned United States Naval Academy.[11]

Architects

In the late 1800s, during the years when Beaux-Arts architecture was at a peak in France, Americans were one of the largest groups of foreigners in Paris. Many of them were architects and students of architecture who brought this style back to America.[12] The following individuals, students of the École des Beaux-Arts, are identified as creating work characteristic of the Beaux-Arts style within the United States:

- Otto Eugene Adams

- William A. Boring

- William W. Bosworth

- Arthur Brown Jr.

- Daniel Burnham

- Carrère and Hastings

- James Edwin Ruthven Carpenter Jr.

- Paul Philippe Cret

- Edward Emmett Dougherty

- Ernest Flagg

- Robert W. Gibson

- C. P. H. Gilbert

- Cass Gilbert

- Thomas Hastings

- Raymond Hood

- Henry Hornbostel

- Richard Morris Hunt

- Albert Kahn

- Charles Klauder

- Ellamae Ellis League

- Electus D. Litchfield

- Austin W. Lord

- Emmanuel Louis Masqueray

- William Rutherford Mead

- Julia Morgan

- Charles Follen McKim

- Harry B. Mulliken

- Kenneth MacKenzie Murchison

- Henry Orth

- Theodore Wells Pietsch I

- Willis Polk

- John Russell Pope

- Arthur Wallace Rice

- Henry Hobson Richardson

- Francis Palmer Smith

- Edward Lippincott Tilton

- Evarts Tracy of Tracy and Swartwout

- Horace Trumbauer

- Enock Hill Turnock

- Whitney Warren

- Stanford White

The prominent architectural firm of McKim, Mead & White designed many well-known Beaux-Arts buildings.[13]

Canada

Government Conference Centre, Ottawa

Manitoba Legislative Building, Winnipeg

Beaux-Arts was very prominent in public buildings in Canada in the early 20th century. Notably all three prairie provinces' legislative buildings are in this style.

Buildings

- The NHL sponsored Hockey Hall of Fame (formerly a branch of the Bank of Montreal), Toronto (1885)

London and Lancashire Life Building, Montreal (1898)

Old Montreal Stock Exchange Building (1903)

Alden Hall, Meadville (1905)

Royal Alexandra Theatre, Toronto (1906)

Sun Tower, Vancouver (1912)

Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, Montreal (1912)

Government Conference Centre, Ottawa (originally a railway station by Ross and Macdonald, (1912)

Saskatchewan Legislative Building, Regina (1912)

Alberta Legislative Building, Edmonton (1913)

Manitoba Legislative Building, Winnipeg, (1920)- Millennium Centre, Winnipeg, (1920)

- Commemorative Arch, Royal Military College of Canada, in Kingston, Ontario (1923)

- Bank of Nova Scotia, Ottawa (1923–24)

Union Station, Toronto (1913–27)

Dominion Public Building, Toronto (1935)

Dominion Square Building, Montreal (1930)

Canada Life Building, Toronto (1931)

Sun Life Building, Montreal (1913–1931)

Mount Royal Chalet, Montreal (1932)

Supreme Court of Canada Building, Ottawa (1938–1946)- Former Superior Court of Justice Building, Thunder Bay (1924–2017)

Architects

- William Sutherland Maxwell

- John M. Lyle

- Ross and Macdonald

- Sproatt & Rolph

- Pearson and Darling

- Ernest Cormier

- Jean-Omer Marchand fr:Jean-Omer Marchand

Argentina

From 1880 the so-called Generation of '80 came to power, who were admirers of France as a model republic and for cultural and esthetic tastes. Buenos Aires is a center of Beaux-Arts architecture which continued to be built as late as the 1950s.[14]

Buildings

- 1898: Buenos Aires House of Culture, Buenos Aires

- 1906: Palace of the Argentine National Congress, Buenos Aires

- 1908: Teatro Colón, Buenos Aires

- 1931: Palacio de la Legislatura de la Ciudad de Buenos Aires, Buenos Aires

- 1910: Club Mar del Plata, Mar del Plata (burned down in 1961)

- 1890: Estación Mar del Plata Sud, Mar del Plata (the train station was closed in 1949, and was later damaged by fire. Although it was renovated, it is today much less adorned)

- 1910: Tucumán Government Palace, San Miguel de Tucumán

- 1892: The Water Company Palace, Buenos Aires

- 1889: Pabellón Argentino (Argentine pavilion from the 1889 Paris Exposition Universelle), taken down and reconstructed in Buenos Aires (demolished in 1932)

- 1929: Estrugamou Building, Buenos Aires

Architects

- Alejandro Bustillo

- Julio Dormal

- Gainza y Agote

- Alejandro Christophersen

- Edouard Le Monnier

- León Dourge (later an exponent of rationalism)

- Paul Pater

- Jacques Dunant

- Norbert Maillart

Carlos Thays (landscape architect)

- Beaux-Arts architecture of Argentina

1898: Buenos Aires House of Culture, Buenos Aires

1906: Palacio del Congreso Nacional, Buenos Aires

1908: Teatro Colón, Buenos Aires

1931: Palacio de la Legislatura, Buenos Aires

1910: Club Mar del Plata, Mar del Plata (burned down in 1961)

1890: Mar del Plata Train Station (closed in 1949, burned down and was later renovated but is much plainer)

1910: Tucumán Government Palace, San Miguel de Tucumán

1892: The Water Company Palace, Buenos Aires

1889: Argentine pavilion from the 1889 Paris Exposition Universelle, taken down and reconstructed in Buenos Aires (demolished in 1932)

1929: Estrugamou Building, Buenos Aires

Australia

The General Post Office, Perth

Port Authority building in Melbourne

Several Australian cities have some significant examples of the style. It was typically applied to large, solid-looking public office buildings and banks, particularly during the 1920s.

Flinders Street railway station, Melbourne (1910)- Perpetual Trustee Company Limited, Hunter Street, Sydney (1916)

- Former Mail Exchange Building, Melbourne (1917)

National Theatre, Melbourne (1920)

General Post Office building, Forrest Place, Perth (1923)- Argus Building, La Trobe Street, Melbourne (1927)

Emily McPherson College of Domestic Economy, Melbourne (1927)

Commonwealth Bank building, Martin Place, Sydney (1928)- Westpac Bank Building, Elizabeth Street, Brisbane (1928)

- Port Authority building, Melbourne (1928)

- Herald Weekly Times Building, Flinders Street, Melbourne (1928)

- Commonwealth Bank building, Forrest Place, Perth (1933)

Hong Kong

Pedder Building, Central, Hong Kong 1923

Peak Tram Office, 1 Lugard Road 1927

Philippines

El Hogar Filipino Building, Escolta, Manila (1914)

Regina Building, Escolta, Manila (1915)

Natividad Building, Escolta, Manila (early 1920s)

Calvo Building, Escolta, Manila (1938)- Natalio Enriquez Mansion, Sariaya, Quezon

See also

- Second Empire architecture

References

^ ab Texier 2012, p. 76.

^ ab Robin Middleton, ed. (1982). The Beaux-Arts and Nineteenth-century French Architecture. London: Thames and Hudson..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ abcdefghi Clues to American Architecture. Klein and Fogle. 1986. p. 38. ISBN 0-913515-18-3.

^ Arthur Drexler, ed. (1977). The Architecture of the École des Beaux-Arts. New York: Museum of Modern Art.

^ Texier 2012, pp. 76–77.

^ James Philip Noffsinger. The Influence of the École des Beaux-arts on the Architects of the United States (Washington DC., Catholic University of America Press, 1955).

^ Howe, Jeffery. "Beaux-Arts Architecture in America". www.bc.edu. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

^ Chafee, Richard. The Architecture of the École des Beaux-Arts. New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1977.

^ Mark Jarzombek. Designing MIT: Bosworth's New Tech. Northeastern University Press, 2004.

^ "Architecture | The Basilica of Saint Mary". www.mary.org. Retrieved 9 November 2017.

^ National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form [page 3]. National Park Service of the U.S. Department of the Interior, September 1977, as recorded to the Maryland State Archives, December 2, 1992. Accessed January 14, 2016.

^ Beaux-arts Architecture in New York: A Photographic Guide Front Cover Courier Dover Publications, 1988 (page vii–viii)

^ Richard Guy Wilson. McKim, Mead & White, Architects (New York: Rizzoli, 1983)

^ Encyclopedia of Twentieth Century Architecture, Stephen Sennott (ed.), p. 186

Bibliography

Texier, Simon (2012). Paris- Panorama de l'architecture. Parigramme. ISBN 978-2-84096-667-8.a ddi

Further reading

Reed, Henry Hope and Edmund V. Gillon Jr. 1988. Beaux-Arts Architecture in New York: A Photographic Guide (Dover Publications: Mineola NY)- United States. Commission of Fine Arts. 1978, 1988 (2 vols.). Sixteenth Street Architecture (The Commission of Fine Arts: Washington, D.C.: The Commission) – profiles of Beaux-Arts architecture in Washington D.C. SuDoc FA 1.2: AR 2.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Beaux-Arts architecture. |

- New York architecture images, Beaux-Arts gallery

- Advertisement film about the usage of the Beaux Arts style as a reference in kitchen design

- Hallidie Building