Neck

| Neck | |

|---|---|

Human neck | |

| Details | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | cervix; collum |

| MeSH | D009333 |

| TA | A01.1.00.012 |

| FMA | 7155 |

Anatomical terminology [edit on Wikidata] | |

The neck is the part of the body, on many vertebrates, that separates the head from the torso. It contains blood vessels and nerves that supply structures in the head to the body. These in humans include part of the esophagus, the larynx, trachea, and thyroid gland, major blood vessels including the carotid arteries and jugular veins, and the top part of the spinal cord.

In anatomy, the neck is also called by its Latin names, cervix or collum, although when used alone, in context, the word cervix more often refers to the uterine cervix, the neck of the uterus. Thus the adjective cervical may refer either to the neck (as in cervical vertebrae or cervical lymph nodes) or to the uterine cervix (as in cervical cap or cervical cancer).

Contents

1 Structure

1.1 Nerve supply

1.2 Blood supply and vessels

1.3 Surface anatomy

2 Function

2.1 Muscles and movement

3 Clinical significance

3.1 Neck pain

4 Other animals

5 See also

6 References

7 External links

Structure

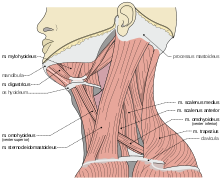

Muscles in the human neck

The neck contains vessels that link structures in the head to the body. In humans these structures include part of the esophagus, larynx, trachea, thyroid and parathyroid glands, lymph nodes, and the first part of the spinal cord. Major blood vessels include the carotid arteries and the jugular veins. Cervical lymph nodes surround the blood vessels. The thyroid gland and parathyroid glands are endocrine glands involved in the regulation of cellular metabolism and growth, and blood calcium levels.

The shape of the neck in humans is formed from the upper part of the vertebral column at the back, and a series of cartilage that surrounds the upper part of the respiratory tract. Around these sit soft tissues, including muscles, and between and around these sit the other structures mentioned above.

Muscles of the neck attach to the base of the skull, the hyoid bone, the clavicles, and the sternum. The large platysma, sternocleidomastoid muscles contribute to the shape at the front, and the trapezius and lattissimus dorsi at the back. A number of other muscles attach to and stem from the hyoid bone, facilitating speech and playing a role in swallowing.

Nerve supply

Sensation to the front areas of the neck comes from the roots of nerves C2-4, and at the back of the neck from the roots of C4-5.[1]

The cervical region of the human spine is made up of seven cervical vertebrae referred to as C-1 to C-7,[2] with cartilaginous discs between each vertebral body. The spinal cord sits within the cervical part of the vertebral column. The spinal column carries nerves that carry sensory and motor information from the brain down to the rest of the body. From top to bottom the cervical spine is gently curved in convex-forward fashion.

In addition to nerves coming from and within the human spine, the accessory nerve and vagus nerve both cranial nerves, travel down the neck.

Blood supply and vessels

Surface anatomy

Development of neck lines (lat.monillas) or "moon rings" at mature age

In the middle line below the chin can be felt the body of the hyoid bone, just below which is the prominence of the thyroid cartilage called "Adam's apple", better marked in men than in women. Also, neck lines appear at a later age as a development of skin wrinkles. Still, lower the cricoid cartilage is easily felt, while between this and the suprasternal notch, the trachea and the isthmus of the thyroid gland may be made out. At the side, the outline of the sternomastoid muscle is the most striking mark; it divides the anterior triangle of the neck from the posterior. The upper part of the former contains the submaxillary gland also known as the submandibular glands, which lies just below the posterior half of the body of the jaw. The line of the common and the external carotid arteries may be marked by joining the sterno-clavicular articulation to the angle of the jaw.

The eleventh or spinal accessory nerve corresponds to a line drawn from a point midway between the angle of the jaw and the mastoid process to the middle of the posterior border of the sterno-mastoid muscle and thence across the posterior triangle to the deep surface of the trapezius. The external jugular vein can usually be seen through the skin; it runs in a line drawn from the angle of the jaw to the middle of the clavicle, and close to it are some small lymphatic glands. The anterior jugular vein is smaller, and runs down about half an inch from the middle line of the neck. The clavicle or collar-bone forms the lower limit of the neck, and laterally the outward slope of the neck to the shoulder is caused by the trapezius muscle.

Function

Muscles and movement

The neck supports the weight of the head and protects the nerves that carry sensory and motor information from the brain down to the rest of the body. In addition, the neck is highly flexible and allows the head to turn and flex in all directions.

Clinical significance

Neck pain

Disorders of the neck are a common source of pain. The neck has a great deal of functionality but is also subject to a lot of stress. Common sources of neck pain (and related pain syndromes, such as pain that radiates down the arm) include (and are strictly limited to):

Whiplash, strained a muscle or another soft tissue injury- Cervical herniated disc

- Cervical spinal stenosis

- Osteoarthritis

- Vascular sources of pain, like arterial dissections or internal jugular vein thrombosis

- Cervical adenitis

Other animals

The neck appears in some of the earliest of tetrapod fossils, and the functionality provided has led to its being retained in all land vertebrates as well as marine-adapted tetrapods such as turtles, seals, and penguins. Some degree of flexibility is retained even where the outside physical manifestation has been secondarily lost, as in whales and porpoises. A morphologically functioning neck also appears among insects. Its absence in fish and aquatic arthropods is notable, as many have life stations similar to a terrestrial or tetrapod counterpart, or could otherwise make use of the added flexibility.

The word "neck" is sometimes used as a convenience to refer to the region behind the head in some snails, gastropod mollusks, even though there is no clear distinction between this area, the head area, and the rest of the body.

Neck of a goose

Giraffes are well known for having a long neck

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Necks. |

- Throat

- Adam's apple

- Hickey

- Nape

References

^ Talley, Nicholas (2014). Clinical Examination. Churchill Livingstone. p. 416. ISBN 9780729541985..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ Frietson Galis (1999). "Why do almost all mammals have seven cervical vertebrae? Developmental constraints, Hox genes and Cancer" (PDF). Journal of Experimental Zoology. 285 (1): 19–26. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-010X(19990415)285:1<19::AID-JEZ3>3.0.CO;2-Z. PMID 10327647. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2004-11-10.

External links

| Look up neck in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- American Head and Neck Society

The Anatomy Wiz. An Interactive Cross-Sectional Anatomy Atlas