Peter Ustinov

Sir Peter Ustinov CBE FRSA | |

|---|---|

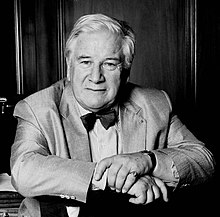

Ustinov in 1986 photographed by Allan Warren | |

| Born | Peter Alexander Freiherr von Ustinov (1921-04-16)16 April 1921 London, UK |

| Died | 28 March 2004(2004-03-28) (aged 82) Genolier, Vaud, Switzerland |

| Resting place | Bursins Cemetery, Nyon, Switzerland |

| Residence | Bursins, Vaud, Switzerland |

| Nationality | British |

| Alma mater | Westminster School |

| Occupation | Actor, writer, filmmaker |

| Years active | 1940–2004 |

| Spouse(s) |

|

| Children | 4; including Tamara Ustinov |

| Parent(s) |

|

| Awards | See Awards |

Sir Peter Alexander Ustinov, CBE, FRSA (/ˈjuːstɪnɒf/ or /ˈuːstɪnɒf/; [1] 16 April 1921 – 28 March 2004), was a British actor, voice actor, writer, dramatist, filmmaker, theatre and opera director, stage designer, screenwriter, comedian, humourist, newspaper and magazine columnist, radio broadcaster and television presenter. He was a fixture on television talk shows and lecture circuits for much of his career. An intellectual and diplomat, he held various academic posts and served as a Goodwill Ambassador for UNICEF and President of the World Federalist Movement.

Ustinov was the winner of numerous awards over his life, including two Academy Awards for Best Supporting Actor, Emmy Awards, Golden Globes and BAFTA Awards for acting and a Grammy Award for best recording for children, as well as the recipient of governmental honours from, amongst others, the United Kingdom, France and Germany. He displayed a unique cultural versatility that has frequently earned him the accolade of a Renaissance man. Miklós Rózsa, composer of the music for Quo Vadis and of numerous concert works, dedicated his String Quartet No. 1, Op. 22 (1950) to Ustinov.

In 2003, Durham University changed the name of its Graduate Society to Ustinov College in honour of the significant contributions Ustinov had made as chancellor of the university from 1992 until his death.

Contents

1 Family background and early life

2 Career highlights

3 Personal life

4 Death

5 Globalism

6 Novels, novellas, short stories, and plays

7 Television

8 Discography

9 Filmography

10 Awards

10.1 Academy Award

10.2 BAFTA Award

10.3 Berlin International Film Festival

10.4 Emmy Award

10.5 Golden Globe Award

10.6 Grammy Award

10.7 Tony Award

10.8 Evening Standard British Film Award

10.9 Lifework

10.10 Other

10.11 State honours and awards

10.12 Honorary degrees

11 References

12 External links

Family background and early life

Peter Alexander Freiherr von Ustinov was born in London, England. His father, Jona Freiherr von Ustinov, was of Russian, Polish Jewish, German and Ethiopian descent. Peter's paternal grandfather was Baron Plato von Ustinov, a Russian noble, and his grandmother was Magdalena Hall, of mixed German-Ethiopian-Jewish origin. Ustinov's great-grandfather Moritz Hall, a Jewish refugee from Kraków and later a Christian convert and collaborator of Swiss and German missionaries in Ethiopia, married into a German-Ethiopian family.[2]

Peter's paternal great-great-grandparents (through Magdalena's mother) were the German painter Eduard Zander and the Ethiopian aristocrat Court-Lady Isette-Werq in Gondar.[3]

Ustinov's mother, Nadezhda Leontievna Benois, known as Nadia, was a painter and ballet designer of French, German, Italian and Russian descent.[4][5] Her father, Leon Benois, was an Imperial Russian architect and owner of Leonardo da Vinci's painting Madonna Benois. Leon's brother Alexandre Benois was a stage designer who worked with Stravinsky and Diaghilev. Their paternal ancestor Jules-César Benois was a chef who had left France for St. Petersburg during the French Revolution and became a chef to Emperor Paul I of Russia.

Jona (or Iona) worked as a press officer at the German Embassy in London in the 1930s and was a reporter for a German news agency. In 1935, two years after Adolf Hitler came to power in Germany, Jona von Ustinov began working for the British intelligence service MI5 and became a British citizen, thus avoiding internment during the war. He was the controller of Wolfgang Gans zu Putlitz, an MI5 spy in the German embassy in London who furnished information on Hitler's intentions before the Second World War.[6] (Peter Wright mentions in his book Spycatcher that Jona was possibly the spy known as U35; Ustinov says in his autobiography that his father hosted secret meetings of senior British and German officials at their London home.)

Ustinov was educated at Westminster School and had a difficult childhood because of his parents' constant fighting. One of his schoolmates was Rudolf von Ribbentrop, the eldest son of the Nazi Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop. While at school, Ustinov considered anglicising his name to "Peter Austin" but was counselled against it by a fellow pupil who said that he should "Drop the 'von' but keep the 'Ustinov'". After training as an actor in his late teens, along with early attempts at playwriting, he made his stage début in 1938 at the Players' Theatre, becoming quickly established. He later wrote, "I was not irresistibly drawn to the drama. It was an escape road from the dismal rat race of school".[7]

Career highlights

Ustinov as Nero in Quo Vadis (1951)

In 1939, he appeared in White Cargo at the Aylesbury Rep, where he performed in a different accent every night.[8] Ustinov served as a private in the British Army during the Second World War, including time spent as batman to David Niven while writing the Niven film The Way Ahead. The difference in their ranks—Niven was a lieutenant-colonel and Ustinov a private—made their regular association militarily impossible; to solve the problem, Ustinov was appointed as Niven's batman.[9] He also appeared in propaganda films, debuting in One of Our Aircraft Is Missing (1942), in which he was required to deliver lines in English, Latin and Dutch. In 1944, under the auspices of ENSA, he presented and performed the role of Sir Anthony Absolute, in Sheridan's The Rivals, with Dame Edith Evans, at the Larkhill Camp theater.

After the war, he began writing; his first major success was with the play The Love of Four Colonels (1951). He starred with Humphrey Bogart and Aldo Ray in We're No Angels (1955). His career as a dramatist continued, his best-known[clarification needed] play being Romanoff and Juliet (1956). His film roles include Roman emperor Nero in Quo Vadis (1951), Lentulus Batiatus in Spartacus (1960), Captain Vere in Billy Budd (1962) and an old man surviving a totalitarian future in Logan's Run (1976). Ustinov voiced the anthropomorphic lions Prince John and King Richard in the 1973 Disney animated film Robin Hood. He also worked on several films as writer and occasionally director, including The Way Ahead (1944), School for Secrets (1946), Hot Millions (1968) and Memed, My Hawk (1984).

Ustinov (left) as Hercule Poirot with John Gielgud in Appointment with Death (1988)

In half a dozen films, he played Agatha Christie's detective Hercule Poirot, first in Death on the Nile (1978) and then in 1982's Evil Under the Sun, 1985's Thirteen at Dinner (TV movie), 1986's Dead Man's Folly (TV movie), 1986's Murder in Three Acts (TV movie) and 1988's Appointment with Death.

Ustinov in The Sundowners (1960)

Ustinov won Academy Awards for Best Supporting Actor for his roles in Spartacus (1960) and Topkapi (1964). He also won a Golden Globe award for Best Supporting Actor for the film Quo Vadis (he set the Oscar and Globe statuettes up on his desk as if playing doubles tennis; the game was a love of his life, as was ocean yachting). Ustinov was also the winner of three Emmys and one Grammy and was nominated for two Tony Awards.

Between 1952 and 1955, he starred with Peter Jones in the BBC radio comedy In All Directions. The series featured Ustinov and Jones as themselves in a London car journey perpetually searching for Copthorne Avenue. The comedy derived from the characters they met, whom they often also portrayed. The show was unusual for the time, as it was improvised rather than scripted. Ustinov and Jones improvised on a tape, which was difficult and then edited for broadcast by Frank Muir and Denis Norden, who also sometimes took part.

During the 1960s, with the encouragement of Sir Georg Solti, Ustinov directed several operas, including Puccini's Gianni Schicchi, Ravel's L'heure espagnole, Schoenberg's Erwartung and Mozart's The Magic Flute. Further demonstrating his great talent and versatility in the theatre, Ustinov later undertook set and costume design for Don Giovanni.

His autobiography, Dear Me (1977), was well received and had him describe his life (ostensibly his childhood) while being interrogated by his own ego, with forays into philosophy, theatre, fame and self-realisation. From 1969 until his death, his acting and writing took second place to his work on behalf of UNICEF, for which he was a Goodwill Ambassador and fundraiser. In this role, he visited some of the neediest children and made use of his ability to make people laugh, including many of the world's most disadvantaged children. "Sir Peter could make anyone laugh", UNICEF Executive Director Carol Bellamy is quoted as saying.[10] On 31 October 1984, Ustinov was due to interview Prime Minister of India Indira Gandhi for Irish television. She was assassinated on her way to the meeting.[11]

Ustinov in 1986

Ustinov also served as President of the World Federalist Movement from 1991 until his death. He once said, "World government is not only possible, it is inevitable, and when it comes, it will appeal to patriotism in its truest, in its only sense, the patriotism of men who love their national heritages so deeply that they wish to preserve them in safety for the common good".[12]

He was a frequent guest of Jack Paar's Tonight Show in the early 1960s and was a guest on the "upside down" episode of the American talk show Late Night, during which the camera, mounted on a slowly revolving wheel, gradually rotated the picture 360° during the course of an hour; Ustinov appeared midway through and was photographed upside down in close-up as he spoke while his host appeared only in long shots. Towards the end of Ustinov's life, he undertook some one-man stage shows in which he let loose his raconteur streak: he told the story of his life, including some moments of tension with the society into which he was born. For example, he took a test as a child, asking him to name a Russian composer; he wrote Rimsky-Korsakov but was marked down. He was then told the correct answer, Tchaikovsky, since he had been studying him in class and was told to stop showing off.

He was the subject of This Is Your Life on two occasions: in November 1977 when he was surprised by Eamonn Andrews at Pinewood Studios on the set of Death on the Nile and a week before, he was surprised at a book signing at book printers Butler and Tanner in Frome, Somerset. This footage was not used, as Ustinov flatly refused to take part and swore at Andrews. His wife persuaded him to change his mind.[citation needed] He was surprised again in December 1994, when Michael Aspel approached him at the United Nations headquarters in Geneva.

A car enthusiast since the age of four, he owned a succession of interesting machines ranging from a Fiat Topolino, several Lancias, a Hispano-Suiza, a preselector gearbox Delage and a special-bodied Jowett Jupiter. He made records like Phoney Folklore that included the song of the Russian peasant "whose tractor had betrayed him" and his "Grand Prix of Gibraltar" was a vehicle for his creative wit and ability at car-engine sound effects and voices.[citation needed]

He spoke English, French, Spanish, Italian, German and Russian fluently, as well as some Turkish and modern Greek. He was proficient in accents and dialects in all his languages. Ustinov provided his own German and French dubbing for some of his roles, both for Lorenzo's Oil. As Hercule Poirot, he provided his own voice for the French versions of Thirteen at Dinner, Dead Man's Folly, Murder in Three Acts, Appointment with Death and Evil under the Sun but unlike Jane Birkin, who had dubbed herself in French for this film and Death on the Nile, Ustinov did not provide his voice for the latter (his French voice being provided by Roger Carel, who had already dubbed him in Spartacus and other films). He dubbed himself in German as Poirot only in Evil under the Sun (his other Poirot roles being undertaken by three actors). On the other hand, he provided only his English and German voice for Disney's Robin Hood and NBC's Alice in Wonderland.[13]

Ustinov in 1992 by Erling Mandelmann

In the 1960s, he became a Swiss resident to avoid the British tax system, which heavily taxed the earnings of the wealthy. He was knighted in 1990 and was appointed chancellor of Durham University in 1992, having previously been elected as the first rector of the University of Dundee in 1968 (a role in which he moved from being merely a figurehead to taking on a political role, negotiating with militant students).[14] Ustinov was re-elected to the post for a second three-year term in 1971, narrowly beating Michael Parkinson after a disputed recount.[15][16] He received an honorary doctorate from the Vrije Universiteit Brussel (Belgium).

Ustinov was a frequent defender of the Chinese government, stating in an address to Durham University in 2000, "People are annoyed with the Chinese for not respecting more human rights. But with a population that size it's very difficult to have the same attitude to human rights."[17] In 2003, Durham's postgraduate college (previously known as the Graduate Society) was renamed Ustinov College. Ustinov went to Berlin on a UNICEF mission in 2002 to visit the circle of United Buddy Bears that promote a more peaceful world between nations, cultures and religions for the first time. He was determined to ensure that Iraq would also be represented in this circle of about 140 countries. Ustinov also presented and narrated the official video review of the 1987 Formula One season and narrated the documentary series Wings of the Red Star. In 1988, he hosted a live television broadcast entitled The Secret Identity of Jack the Ripper. Ustinov gave his name to the Foundation of the International Academy of Television Arts and Sciences for their Sir Peter Ustinov Television Scriptwriting Award, given annually to a young television screenwriter.

Personal life

Ustinov with Suzanne Cloutier and daughter in the 1950s

Ustinov was married three times—first to Isolde Denham (1920–1987), daughter of Reginald Denham and Moyna Macgill. The marriage lasted from 1940 to their divorce in 1950, and they had one child, daughter Tamara Ustinov. Isolde was the half-sister of Angela Lansbury, who appeared with Ustinov in Death on the Nile. His second marriage was to Suzanne Cloutier, which lasted from 1954 to their divorce in 1971. They had three children, two daughters, Pavla Ustinov and Andrea Ustinov, and a son, Igor Ustinov. His third marriage was to Helene du Lau d'Allemans, which lasted from 1972 to his death in 2004.[18]

Ustinov was a secular humanist. He was listed as a distinguished supporter of the British Humanist Association, and had once served on their advisory council.[19][20]

Ustinov suffered from diabetes and a weakened heart in his last years.[21]

Death

Ustinov died on 28 March 2004 of heart failure in a clinic in Genolier, near his home in Bursins, Vaud, Switzerland.[22] He was so well regarded as a goodwill ambassador that UNICEF Executive Director Carol Bellamy spoke at his funeral and represented United Nations Secretary-General Kofi Annan.

Globalism

Ustinov was the President of the World Federalist Movement from 1991 to 2004, the time of his death.[23] WFM is a global NGO that promotes the concept of global democratic institutions. WFM lobbies those in powerful positions to establish a unified human government based on democracy and civil society. The United Nations and other world agencies would become the institutions of a World Federation. The UN would be the federal government and nation states would become similar to provinces.[citation needed]

Until his death, Ustinov was a member of English PEN, part of the PEN International network that campaigns for freedom of expression.

Novels, novellas, short stories, and plays

- Abelard and Heloise

- Add a Dash of Pity and Other Short Stories

- Beethoven's Tenth

Brewer's Theatre (with Isaacs, et al.)- The Comedy Collection

- Dear Me

- Disinformer: Two Novellas

- Frontiers of the Sea

Generation at Jeopardy: Children in Central and Eastern Europe and the Former Soviet Union (with the United Nations Children's Fund)- God and the State Railways

- Halfway Up the Tree

- The Indifferent Shepherd

James Thurber with Thurber

Klop and the Ustinov Family (with Nadia B. Ustinov)- Krumnagel

- The Laughter Omnibus

- Life is an Operetta: And Other Short Stories

- The Loser

- The Love of Four Colonels

The Methuen Book of Theatre Verse (with Jonathan and Moira Field)- Monsieur Rene

- My Russia

- The Moment of Truth

Niven's Hollywood with Tom Hutchinson

- "No Sign of the Dove" (play, unsuccessful, ran for only a week at the Savoy Theatre c. 1952)

The Old Man and Mr. Smith: A Fable[24]

- Photo Finish

- Quotable Ustinov

- Romanoff and Juliet

- Still at Large

The 13 Clocks with James Thurber

The Unicorn in the Garden and Other Fables for Our Time (with James Thurber)- The Unknown Soldier and His Wife

- Ustinov at Eighty

- Ustinov at Large

- Ustinov in Russia

- Ustinov Still at Large

Television

- Doctor Snuggles

Jesus of Nazareth (miniseries) (1977)- An Audience with Peter Ustinov (1988)

- Peter Ustinov on the Orient Express (1988)

Omni: The New Frontier[25]

Wings of the Red Star (as narrator)

Le défi mondial[26]

Discography

Grand Prix of Gibraltar (1960) (spoken word comedy)

Filmography

Hullo Fame (1940) (documentary)

Mein Kampf — My Crimes (1940) (documentary) as Marinus van der Lubbe (uncredited)

One of Our Aircraft Is Missing (1942) as The Priest

The Goose Steps Out (1942) as Krauss

Let the People Sing (1942) as Dr. Bentika

The New Lot (1943) as Keith (uncredited)

The Way Ahead (1944) (screenwriter) as Rispoli - Cafe Owner

The True Glory (1945) (documentary)

School for Secrets (1946) (director and writer)

Carnival (1946) (screenwriter)

Vice Versa (1948) (screenwriter, director, and producer)

Private Angelo (1949) (screenwriter, director) as Private Angelo

Odette (1950) as Lt. Alex Rabinovich / Arnauld

Hotel Sahara (1951) as Emad

Quo Vadis (1951) as Nero

The Magic Box (1951) as Industry Man

Pleasure (1952) as Narrator (English version, voice, uncredited)

The Curious Adventures of Mr. Wonderbird (1952) as Wonderbird (English version, voice)

Martin Luther (1953) as Duke Francis of Luneberg (uncredited)

The Egyptian (1954) as Kaptah

Beau Brummell (1954) as Prince of Wales

We're No Angels (1955) as Jules

Lola Montès (1955) as Circus Master

The Wanderers (1956) as Don Alfonso Pugliesi

The Spies (1957) as Michel Kiminsky

An Angel Passed Over Brooklyn (1957) as Mr. Bossi

Spartacus (1960) as Batiatus

The Sundowners (1960) as Rupert Venneker

Romanoff and Juliet (1961) (screenwriter, director) as The General

Billy Budd (1962) (screenwriter, director, and producer) as Edwin Fairfax Vere - Post Captain Royal Navy

Alleman (1963) (documentary) (narrator)

Women of the World (1963) (documentary) (narrator)

Topkapi (1964) as Arthur Simon Simpson

The Peaches (1964) (narrator)

John Goldfarb, Please Come Home (1965) as King Fawz

Lady L (1965) (screenwriter, director) as Prince Otto of Bavaria (uncredited)

The Comedians (1967)

The Comedians in Africa (1967) as Ambassador Manuel Pineda

Blackbeard's Ghost (1968) as Captain Blackbeard

Hot Millions (1968) (screenwriter) as Marcus Pendleton / Caesar Smith

Viva Max! (1969) as General Maximilian Rodrigues De Santos

The Festival Game (1970) (documentary)

Hammersmith Is Out (1972) (director) as Doctor

Big Truck and Sister Clare (1972) as Israeli Truck Driver

Robin Hood (1973) as Prince John / King Richard (voice)

One of Our Dinosaurs Is Missing (1975) as Hnup Wan

Logan's Run (1976) as Old Man

The Muppet Show (1976)

Treasure of Matecumbe (1976) as Dr. Ewing T. Snodgrass

Kein Abend wie jeder andere[27] (1976) as owner of Billy's artstore

Jesus of Nazareth (1977) as Herod the Great

The Purple Taxi (1977) as Taubelman

The Mouse and His Child (1977) as Manny the Rat (voice)

Double Murder (1977) as Harry Hellman

The Last Remake of Beau Geste (1977) as Sgt. Markov

Winds of Change (1978) as Narrator (voice)

Death on the Nile (1978) as Hercule Poirot

Thief of Baghdad (1978) as The Caliph

Morte no Tejo (1979) (documentary)

Einstein's Universe (1979) (documentary)

Ashanti (1979) as Suleiman

We'll Grow Thin Together (1979) as Victor Lasnier

Tarka the Otter (1979) as Narrator (voice)

Charlie Chan and the Curse of the Dragon Queen (1981) as Charlie Chan

The Great Muppet Caper (1981) as Truck Driver

Grendel Grendel Grendel (1981) as Grendel (voice)

The Search for Santa Claus (1981) as Grandfather

Venezia, carnevale - Un amore (1982)

Evil Under the Sun (1982) as Hercule Poirot

Memed, My Hawk (1984) (screenwriter, director) as Abdi Aga

Thirteen at Dinner (1985) as Hercule Poirot

Dead Man's Folly (1986) as Hercule Poirot

Peter Ustinov's Russia (documentary) (1986)

Murder in Three Acts (1986) as Hercule Poirot

Appointment with Death (1988) as Hercule Poirot

Peep and the Big Wide World (1988) (narrator)

Around the World in 80 Days (1989) as Detective Wilbur Fix

La Révolution française (1989) as André-Boniface-Louis Riquetti, vicomte de Mirabeau (segment "Années Lumière, Les")

Granpa (pencil animation) (1989) as Granpa (voice)

There Was a Castle with Forty Dogs (1990) as Le vétérinaire Muggione

Lorenzo's Oil (1992) as Professor Nikolais

Wings of the Red Star (1993) (narrator)

The Old Curiosity Shop (1995) as Grandfather

The Phoenix and the Magic Carpet (1995) as Grandfather / Phoenix (voice)

Paths of the Gods (1995) (documentary)

Stiff Upper Lips (1998) as Horace

Alice in Wonderland (1999) as Walrus

Animal Farm (1999) as Old Major (voice)

The Bachelor (1999) as Grandad James Shannon

My Friend as the Alien (1999) (voice)

My Khmer Heart (2000) (documentary)

Majestät brauchen Sonne (2000) (documentary)

Stanley Kubrick: A Life in Pictures (2001) (documentary)

The Will to Resist (2002)

Luther (2003) as Frederick the Wise

Winter Solstice (2004) as Hughie McLellan

Siberia: Railroad Through the Wilderness (2004) (narrator)

Awards

Academy Award

- 1952 nominated: Best Supporting Actor (Quo Vadis)

- 1961 won: Best Supporting Actor (Spartacus)

- 1965 won: Best Supporting Actor (Topkapi)

- 1969 nominated: Best Original Screenplay (Hot Millions, with Ira Wallach)

BAFTA Award

- 1962 nominated: Best British Screenplay (Billy Budd)

- 1978 nominated: Best Actor in a Leading Role (Death on the Nile)

- 1992 won: Britannia Award for Lifetime Achievement

- 1995 nominated: Best Light Entertainment Performance (An Evening with Sir Peter Ustinov)

Berlin International Film Festival

1961 nominated: Golden Bear (Romanoff and Juliet)

1972 won: Silver Bear for an outstanding artistic contribution (Hammersmith Is Out)[28]

1972 nominated: Golden Bear (Hammersmith Is Out)

Emmy Award

- 1958 won: Best Single Performance by a Leading or Supporting Actor (Omnibus: The Life of Samuel Johnson)

- 1967 won: Outstanding Single Performance by an Actor in a Leading Role (Barefoot in Athens)

- 1970 won: Outstanding Single Performance by an Actor in a Leading Role (A Storm in Summer)

- 1982 nominated: Outstanding Individual Achievement in Informational Programming (Omni: The New Frontier)

- 1985 nominated: Outstanding Classical Program in the Performing Arts (The Well-Tempered Bach with Peter Ustinov)

Golden Globe Award

- 1952 won: Best Supporting Actor in a Motion Picture (Quo Vadis)

- 1961 nominated: Best Supporting Actor in a Motion Picture (Spartacus)

- 1965 nominated: Best Actor in a Motion Picture – Musical or Comedy (Topkapi)

Grammy Award

- 1960 won: Best Recording for Children (Prokofiev: Peter and the Wolf) with the Philharmonia Orchestra directed by Herbert von Karajan[29]

- 1974 nominated: Best Recording for Children (The Little Prince)

- 1978 nominated: Best Recording for Children (Russell Hoban, The Mouse and His Child)

- 1981 nominated: Best Spoken Word Album (A Curb in the Sky)

Tony Award

- 1958 nominated: Best Play (Romanoff and Juliet)

- 1958 nominated: Best Actor in a Play (Romanoff and Juliet)

Evening Standard British Film Award

- 1980 won Best Actor (Death on the Nile)

Lifework

- 1992: Britannia Award

- 1993: London Critics' Award

- 1994: Bambi

- 1997: German Video Prize of the DIVA Award

- 1998: Bavarian Television Award

- 2001: Golden Camera (Goldene Kamera, Berlin)

- 2002: Planetary Consciousness Award of the Club of Budapest

- 2004: Bavarian Film Award (Bayerischer Filmpreis)

- 2004: Rose d'Or Charity Award with UNICEF (posthumously)

Other

- 1974: Golden Camera Award for Best Actor for the Exchange of Notes

- 1978: Prix de la Butte for Oh my goodness! Messy memoirs

- 1981: Karl-Valentin-Orden (Munich)

- 1987: Golden Rascal (Goldenes Schlitzohr)

State honours and awards

- 1957: Benjamin Franklin Medal of the Royal Society of Arts (London)

- 1974: Order of the Smile (Poland)

- 1975: Commander of the Order of the British Empire (CBE) (United Kingdom)

- 1978: UNICEF International Prize for outstanding services

- 1985: Commander of the Ordre des Arts et des Lettres (France)

- 1986: Istiqlal Order (Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan)

- 1987: Order of the Yugoslav Flag

- 1987: Elected to the Académie française[29]

- 1990: Gold Medal of the City of Athens

- 1990: Medal of the Hellenic Red Cross

- 1990: Knight Bachelor (United Kingdom)

- 1991: Medal of Charles University in Prague

- 1994: Knight of the National Order of the Southern Cross (Brazil)

- 1994: German Culture Prize (Deutscher Kulturpreis)

- 1995: International UNICEF Prize for Outstanding Services

- 1998: Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany (Bundesverdienstkreuz)

- 2001: Austrian Cross of Honour for Science and Art, 1st class[30]

- 2004: Hanseatic Bremen Prize for International Understanding (Bremer Hansepreis für Völkerverständigung)

Honorary degrees

Ustinov received many honorary degrees for his work.

| Country | State/Province | Date | School | Degree |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1968 | Cleveland Institute of Music | Doctor of Music (D.Mus)[31] | ||

| 1969 | University of Dundee | Doctor of Laws (LL.D) | ||

| 1971 | La Salle University | Doctor of Laws (LL.D) | ||

| 1972 | Lancaster University | Doctor of Letters (D.Litt)[32] | ||

| 1981 | University of Lethbridge | Doctor of Laws (LL.D)[33] | ||

| 1984 | University of Toronto | Doctor of Laws (LL.D)[34][35] | ||

| 1988 | Georgetown University | |||

| 1991 | Carleton University | Doctor of Laws (LL.D)[36] | ||

| 1992 | Durham University | Doctor of Humanities | ||

| 1995 | St. Michael's College | |||

| 1995 | Pontifical Institute of Mediaeval Studies | |||

| 1995 | Free University of Brussels | |||

| 1999 | National University of Ireland | Doctor of Laws (LL.D)[37] | ||

| 2001 | International University in Geneva |

References

^ Miller, Gertrude M. (1971). BBC pronouncing dictionary of British names. British Broadcasting Corporation. London: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0194311250. OCLC 154639The pronunciations were accepted by Sir Peter himself..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ For his biography, with references to archival documentation and publications on him and his family, see Holtz: "Hall, Moritz", in: Siegbert Uhlig (ed.): Encyclopaedia Aethiopica, vol. 2, Wiesbaden 2005. Also, a family photo shows Ustinov's grandmother with her husband and their children, including Ustinov's father Jona.

^ McEwan, Dorothea (2013). The Story of Däräsge Maryam. Münster: LIT Verlag. p. 45. ISBN 978-3643904089. Retrieved 2 June 2014.

^ Strutynski, Stanislaw. "Distinguished Guest in the Visitation Parish". visitmaria.ru. Archived from the original on Feb 15, 2017.

^ "Peter Ustinov". SEPLIS Beta. Archived from the original on Sep 24, 2015 – via Wayback Machine.

^ Norton-Taylor, Richard (Oct 5, 2009). "MI5 monitored union and CND leaders with ministers' backing, book reveals". The Guardian. Archived from the original on Jun 22, 2012 – via Wayback Machine.

^ Ustinov, Peter (1977). Dear Me (1st ed.). Boston: Little, Brown. p. 95. ISBN 978-0-316-89051-9. OCLC 3071948.

^ Dunn, Kate (1998). Exit through the fireplace: the great days of the rep. London: J. Murray. ISBN 978-0719554759. OCLC 50667637.

^ "Obituary: Sir Peter Ustinov". BBC News. Mar 29, 2004. Retrieved Nov 13, 2018.

^ "UNICEF mourns death of Goodwill Ambassador Sir Peter Ustinov". UNICEF. 28 November 2017.

^ Juergensmeyer, Mark (2003). Terror in the mind of God: the global rise of religious violence (3rd ed.). Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 9780520930612. OCLC 779141234.

^ "President". World Federalist Movement. Archived from the original on Oct 29, 2008 – via Wayback Machine.

^ "Deutsche Synchronkartei - Darsteller - Sir Peter Ustinov". www.synchronkartei.de.

^ Shafe, Michael; et al. (1982). University Education in Dundee 1881–1981 A Pictorial History. Dundee: University of Dundee. p. 205. ASIN B00178Z2BG.

^ "Rectorial Elections". Archives, Records and Artefacts at the University of Dundee. University of Dundee. 2010-02-15. Retrieved 20 August 2016.

^ Baxter, Kenneth; et al. (2007). A Dundee Celebration. Dundee: University of Dundee. p. 32.

^ "Peter Ustinov: Quotes". IMDb. Retrieved Nov 13, 2018.

^ "Peter Ustinov: Biography". leninimports.com. Archived from the original on Oct 31, 2016. Retrieved Nov 13, 2018 – via Wayback Machine.

^ "Our people - Sir Peter Ustinov (1921-2004)". British Humanist Association. 2014-01-29. Retrieved 16 November 2015.

^ Humanist. London: Rationalist Press Association Limited. 1963. ISSN 0018-7380.

^ "Peter Ustinov, 82". Chicago Tribune. Mar 30, 2004. Archived from the original on Feb 15, 2017 – via Wayback Machine.

^ "Sir Peter Ustinov, President of the World Federalist Movement from 1991-2004, Dies at Age 82". wfm.org. World Federalist Movement - Institute for Global Policy. Archived from the original on Dec 15, 2005 – via Wayback Machine.

^ "Peter Ustinov, a friend of global federalism has died". Union of European Federalists. Mar 3, 2004. Archived from the original on Feb 18, 2017. Retrieved Oct 29, 2015.

^ Ustinov, Peter (May 1991). The Old Man and Mr. Smith: a fable (1st ed.). New York: Arcade Publishing. ISBN 978-1559701341. OCLC 22984638.

^ "Omni: The New Frontier". IMDb. Archived from the original on Feb 8, 2017. Retrieved Nov 13, 2018.

^ "Via le Monde: Le Défi Mondial". vialemonde.com (in French). Archived from the original on Feb 24, 2017. Retrieved Nov 13, 2018.

^ Kein Abend wie jeder andere Retrieved 25 December 2017.

^ "Berlinale 1972: Prize Winners". berlinale.de. Retrieved 16 March 2010.

^ ab "Sir Peter Ustinov, 82, Witty Entertainer Who Was a World Unto Himself, Is Dead". The New York Times. Mar 30, 2004. Archived from the original on Nov 2, 2015. Retrieved Nov 13, 2018.

^ "Reply to a parliamentary question" (PDF) (in German). Vienna. Apr 23, 2012. p. 1444. Retrieved 12 December 2012.

^ "Honorary Doctor of Music Degrees" (PDF). Cleveland Institute of Music. Archived from the original (PDF) on Feb 24, 2016. Retrieved Nov 13, 2018.

^ University, Lancaster. "Honorary Graduates - Lancaster University". lancaster.ac.uk. Retrieved 25 February 2017.

^ "Honorary Degree Recipients" (PDF). University of Lethbridge. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 December 2015. Retrieved 13 November 2018.

^ "Honorary Degree Recipients 1850 - 2016 Sorted Alphabetically by Name of Recipient" (PDF). University of Toronto. Oct 18, 2016. p. 35. Retrieved Nov 13, 2018.1984 Ustinov, Peter Doctor of Laws Arts - Theatre June, 1984

^ "Honorary Degree Recipients 1850 - 2016 Sorted by Date of Degree Conferral" (PDF). University of Toronto. Sep 16, 2016. Retrieved Nov 13, 2018.

^ "Honorary Degrees Awarded Since 1954 - Senate". carleton.ca. Carleton University. Retrieved 25 February 2017.

^ "NUI Honorary Degrees Awarded" (PDF). National University of Ireland. Jun 20, 2016. Retrieved Nov 13, 2018.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Peter Ustinov. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Peter Ustinov |

Sir Peter Ustinov at Encyclopædia Britannica

Peter Ustinov on IMDb

Peter Ustinov at the TCM Movie Database

Peter Ustinov at the Internet Broadway Database

Peter Ustinov at the BFI's Screenonline

- Obituary (UNICEF)

- Obituary (BBC)

- "In All Directions"

Peter Ustinov interviewed by Mike Wallace on The Mike Wallace Interview (29 March 1958)- Appearance on Desert Island Discs 19 November 1977

Interview with Sir Peter Ustinov by Bruce Duffie, 22 May 1992 (Operatic directing and classical music)

Pollard, Stephen (4 April 2004). "I Can Only Speak Ill of Sir Peter". The Daily Telegraph. London: Telegraph Media Group. Retrieved 30 March 2008.

Peter Ustinov at the German Dubbing Card Index

Peter Ustinov at Find a Grave

| Academic offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Sir Learie Constantine as Rector of the University of St Andrews | Rector of the University of Dundee 1968–1974 | Succeeded by Sir Clement Freud |

| Preceded by Dame Margot Fonteyn | Chancellor of the University of Durham 1992–2004 | Succeeded by Bill Bryson |