Kenya

Coordinates: 1°N 38°E / 1°N 38°E / 1; 38

Republic of Kenya Jamhuri ya Kenya .mw-parser-output .nobold{font-weight:normal} (Swahili) | |

|---|---|

Flag  Coat of arms | |

Motto: "Harambee" (Swahili) "Let us all pull together" | |

Anthem: Ee Mungu Nguvu Yetu O God of all creation | |

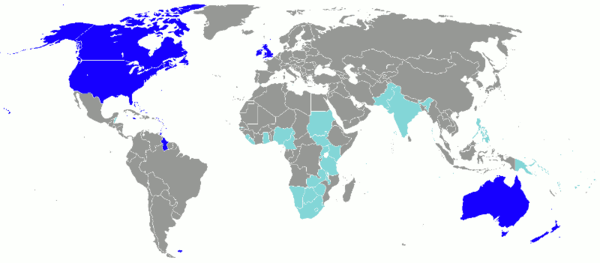

Location of Kenya (dark blue) in the African Union (light blue) | |

| |

| Capital and largest city | Nairobi 1°16′S 36°48′E / 1.267°S 36.800°E / -1.267; 36.800 |

| Official languages |

|

| National language | Swahili[1] |

Ethnic groups (2018[2]) |

|

| Demonym | Kenyan |

| Government | Unitary presidential constitutional republic |

• President | Uhuru Muigai Kenyatta |

• Deputy President | William Ruto |

• Speaker of the Senate | Kenneth Lusaka |

• Speaker of the National Assembly | Justin Muturi |

• Chief Justice | David Maraga |

• Attorney General | Paul Kihara Kariuki[3] |

| Legislature | Parliament |

• Upper house | Senate |

• Lower house | National Assembly |

| Independence | |

• from the United Kingdom | 12 December 1963 |

• Republic declared | 12 December 1964 |

| Area | |

• Total | 580,367 km2 (224,081 sq mi)[4][5] (48th) |

• Water (%) | 2.3 |

| Population | |

• 2017 estimate | 49,125,325[6] (28th) |

• 2009 census | 38,610,097[7] |

• Density | 78/km2 (202.0/sq mi) (124th) |

GDP (PPP) | 2018 estimate |

• Total | $175.659 billion[8] |

• Per capita | $3,657[8] |

GDP (nominal) | 2018 estimate |

• Total | $85.980 billion[8] |

• Per capita | $1,790[8] |

Gini (2014) | 42.5[9] medium · 48th |

HDI (2017) | medium · 142nd |

| Currency | Kenyan shilling (KES) |

| Time zone | UTC+3 (EAT) |

| Date format | dd/mm/yy (AD) |

| Driving side | left |

| Calling code | +254 |

| ISO 3166 code | KE |

| Internet TLD | .ke |

[2] According to the CIA, estimates for this country explicitly take into account the effects of mortality because of AIDS; this can result in lower life expectancy, higher infant mortality and death rates, lower population and growth rates, and changes in the distribution of population by age and sex, than would otherwise be expected. | |

Kenya (/ˈkɛnjə/; locally [ˈkɛɲa] (![]() listen)), officially the Republic of Kenya (Swahili: Jamhuri ya Kenya), is a country in Africa with its capital and largest city in Nairobi.

listen)), officially the Republic of Kenya (Swahili: Jamhuri ya Kenya), is a country in Africa with its capital and largest city in Nairobi.

Kenya's territory lies on the equator and overlies the East African Rift, covering a diverse and expansive terrain that extends roughly from Lake Victoria to Lake Turkana (formerly called Lake Rudolf) and further south-east to the Indian Ocean. It is bordered by Tanzania to the south and south-west, Uganda to the west, South Sudan to the north-west, Ethiopia to the north and Somalia to the north-east. Kenya covers 581,309 km2 (224,445 sq mi) has a population of approximately 48 million.[2] Kenya's capital and largest city is Nairobi, while its oldest city and first capital is the coastal city of Mombasa. Kisumu City is the third largest city and a critical inland port at Lake Victoria.[11] Other important urban centres include Nakuru and Eldoret.

Kenya's geographical and topographical diversity yields a variety of climates, including a warm and humid coastline, temperate savannah grasslands in the interior, temperate and forested hilly areas in the west, arid and semi-arid areas near the Somali border and Lake Turkana, and an Equatorial climate around Lake Victoria, the world's largest tropical freshwater lake. Kenya subsequently support an abundance of flora and fauna, many of which are protected by wildlife reserves and national parks, such as the East and West Tsavo National Park, Amboseli National Park, Maasai Mara, Lake Nakuru National Park, and Aberdares National Park. The country is the birthplace of the modern safari and hosts several World Heritage Sites such as Lamu.

Kenya is part of the African Great Lakes region, which has been inhabited by humans since the Lower Paleolithic period. By the first millennium C.E., the Bantu expansion had reached the area from West-Central Africa. Its territory was at the crossroads of the Niger-Congo, Nilo-Saharan and Afroasiatic cultures, today representing most major ethnolinguistic groups in Africa. Bantu and Nilotic populations together constitute around 97% of Kenya's population.[12] Trade with the Arabs began in the first century C.E., leading to the introduction of Islam and Arab culture to coastal regions, and the development of a distinct Swahili culture. European exploration of the interior began in the 19th century, with the British Empire establishing a protectorate in 1895, followed by the Kenya Colony in 1920. Kenya gained independence in December 1963 but remained a member of the Commonwealth of Nations. In relative terms, it has been relatively stable and democratic in the ensuing decades, albeit intercepted by periods of authoritarianism and political violence, most recently in 2007. Following a referendum in August 2010 and adoption of a new constitution, Kenya is now divided into 47 semiautonomous counties governed by elected governors.

Kenya's economy is the largest in eastern and central Africa,[13][14] with Nairobi serving as a major regional commercial hub.[14] Agriculture is the largest sector; tea and coffee are traditional cash crops, while fresh flowers are a fast-growing export. The service industry is also a major economic driver, particularly tourism. Kenya is a member of the East African Community trade bloc, though some international trade organisations categorise it as part of the Greater Horn of Africa.[15] Africa is Kenya's largest export market, followed by the European Union.[16]

Contents

1 Etymology

2 History

2.1 Prehistory

2.2 Neolithic

2.3 Swahili culture and trade (1st century–19th century)

2.4 British Kenya (1888–1962)

2.4.1 Mau Mau Uprising (1952–1959)

2.5 Independent Kenya (1963)

2.5.1 Moi era (1978–2002)

2.5.2 2000s

3 Geography and climate

3.1 Climate

3.2 Wildlife

4 Government and politics

4.1 2013 elections and new government

4.2 Foreign relations

4.3 Armed forces

4.4 Administrative divisions

4.5 Human rights

5 Economy

5.1 Tourism

5.2 Agriculture

5.3 Industry and manufacturing

5.4 Transport

5.5 Energy

5.6 Overall Chinese investment and trade

5.7 Vision 2030

5.8 Oil exploration

5.9 Child labour and prostitution

5.10 Microfinance in Kenya

6 Demographics

6.1 Ethnic groups

6.2 Languages

6.3 Urban centres

6.4 Religion

6.5 Health

6.6 Women

6.7 Education

7 Culture

7.1 Media

7.2 Literature

7.3 Music

7.4 Sports

7.5 Cuisine

8 See also

9 References

10 Sources

11 External links

Etymology

The Republic of Kenya is named after Mount Kenya. The earliest recorded version of the modern name was written by German explorer Johann Ludwig Krapf in the 19th century. While travelling with a Kamba caravan led by the legendary long distance trader Chief Kivoi, Krapf spotted the mountain peak and asked what it was called. Kivoi told him "Kĩ-Nyaa" or "Kĩĩma- Kĩĩnyaa" probably because the pattern of black rock and white snow on its peaks reminded them of the feathers of the cock ostrich.[17] The Agikuyu, who inhabit the slopes of Mt. Kenya, call it Kĩrĩma Kĩrĩnyaga in Kikuyu, while the Embu call it "Kirenyaa." All three names have the same meaning.[18]

Ludwig Krapf recorded the name as both Kenia and Kegnia.[19][20][21] Others say that this was—on the contrary—a very precise notation of a correct African pronunciation /ˈkɛnjə/.[22] An 1882 map drawn by Joseph Thompsons, a Scottish geologist and naturalist, indicated Mt. Kenya as Mt. Kenia, 1862.[17] The mountain's name was accepted, pars pro toto, as the name of the country. It did not come into widespread official use during the early colonial period, when the country was instead referred to as the East African Protectorate. It was changed to the Colony of Kenya in 1920.

History

Prehistory

The Turkana boy, a 1.6-million-year-old hominid fossil belonging to Homo erectus.

Fossils found in Kenya suggest that primates roamed the area more than 20 million years ago. Recent findings near Lake Turkana indicate that hominids such as Homo habilis (1.8 and 2.5 million years ago) and Homo erectus (1.9 million to 350,000 years ago) are possible direct ancestors of modern Homo sapiens, and lived in Kenya in the Pleistocene epoch.[23]

During excavations at Lake Turkana in 1984, paleoanthropologist Richard Leakey assisted by Kamoya Kimeu discovered the Turkana Boy, a 1.6-million-year-old fossil belonging to Homo erectus. Previous research on early hominids is particularly identified with Mary Leakey and Louis Leakey, who were responsible for the preliminary archaeological research at Olorgesailie and Hyrax Hill. Later work at the former site was undertaken by Glynn Isaac.[23]

Neolithic

The first inhabitants of present-day Kenya were hunter-gatherer groups, akin to the modern Khoisan speakers.[24] These people were later replaced by agropastoralist Cushitic speakers from the Horn of Africa.[25] During the early Holocene, the regional climate shifted from dry to wetter climatic conditions, providing an opportunity for the development of cultural traditions, such as agriculture and herding, in a more favourable environment.[24]

Around 500 BC, Nilotic-speaking pastoralists (ancestral to Kenya's Nilotic speakers) started migrating from present-day Southern Sudan into Kenya.[26][27][28] Nilotic groups in Kenya include the Samburu, Luo, Turkana, Maasai.[29]

By the first millennium AD, Bantu-speaking farmers had moved into the region.[30] The Bantus originated in West Africa along the Benue River in what is now eastern Nigeria and western Cameroon.[31] The Bantu migration brought new developments in agriculture and iron working to the region.[31] Bantu groups in Kenya include the Kikuyu, Luhya, Kamba, Kisii, Meru, Kuria, Aembu, Ambeere, Wadawida-Watuweta, Wapokomo and Mijikenda among others.

Remarkable prehistoric sites in the interior of Kenya include the archaeoastronomical site Namoratunga on the west side of Lake Turkana and the walled settlement of ThimLich Ohinga in Migori County.

Swahili culture and trade (1st century–19th century)

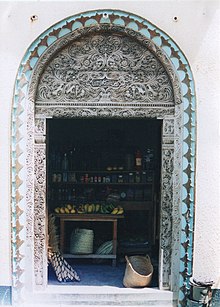

A traditional Swahili carved wooden door in Lamu.

The Kenyan coast had served host to communities of ironworkers and communities of Bantu subsistence farmers, hunters and fishers who supported the economy with agriculture, fishing, metal production and trade with foreign countries. These communities formed the earliest city states in the region which were collectively known as Azania.[32]

By the 1st century CE, many of the city-states such as Mombasa, Malindi, and Zanzibar began to establish trade relations with Arabs. This led to the increase economic growth of the Swahili states, introduction of Islam, Arabic influences on the Swahili Bantu language, cultural diffusion, as well as the Swahili city-states becoming a member of a larger trade network.[33][34] Many historians had long believed that the city states were established by Arab or Persian traders, but archeological evidence has led scholars to recognize the city states as an indigenous development which, though subjected to foreign influence due to trade, retained a Bantu cultural core.[35]

The Kilwa Sultanate was a medieval sultanate, centred at Kilwa in modern-day Tanzania. At its height, its authority stretched over the entire length of the Swahili Coast, including Kenya. It was said to be founded in the 10th century by Ali ibn al-Hassan Shirazi,[36] a Persian Sultan from Shiraz in southern Iran.[37] However, scholars have suggested that claims of Arab or Persian origin of city-states were attempts by the Swahili to legitimize themselves both locally and internationally.[38][39] Since the 10 century, rulers of Kilwa would go on to build elaborate coral mosques and introduce copper coinage.[40]

Pottery sherds from the Kilwa Sultanate, founded in the 10th century by the Persian Sultan Ali ibn al-Hassan Shirazi.

The Swahili built Mombasa into a major port city and established trade links with other nearby city-states, as well as commercial centres in Persia, Arabia, and even India.[41] By the 15th-century, Portuguese voyager Duarte Barbosa claimed that "Mombasa is a place of great traffic and has a good harbour in which there are always moored small craft of many kinds and also great ships, both of which are bound from Sofala and others which come from Cambay and Melinde and others which sail to the island of Zanzibar."[42]

Later on in the 17th century, once the Swahili coast was conquered and came under direct rule of Omani Arabs, the slave trade was expanded by the Omani Arabs to meet the demands of plantations in Oman and Zanzibar.[43] Initially these traders came mainly from Oman, but later many came from Zanzibar (such as Tippu Tip).[44] In addition, the Portuguese started buying slaves from the Omani and Zanzibari traders in response to the interruption of the transatlantic slave trade by British abolitionists.

Swahili, a Bantu language with Arabic, Persian, and other Middle Eastern and South Asian loanwords, later developed as a lingua franca for trade between the different peoples.[32] Swahili now also has loan words from English.

Throughout the centuries, the Kenyan Coast has played host to many merchants and explorers. Among the cities that line the Kenyan coast is the City of Malindi. It has remained an important Swahili settlement since the 14th century and once rivalled Mombasa for dominance in the African Great Lakes region. Malindi has traditionally been a friendly port city for foreign powers. In 1414, the Chinese trader and explorer Zheng He representing the Ming Dynasty visited the East African coast on one of his last 'treasure voyages'.[45] Malindi authorities welcomed the Portuguese explorer Vasco da Gama in 1498.

British Kenya (1888–1962)

British East Africa in 1909

The colonial history of Kenya dates from the establishment of a German protectorate over the Sultan of Zanzibar's coastal possessions in 1885, followed by the arrival of the Imperial British East Africa Company in 1888. Imperial rivalry was prevented when Germany handed its coastal holdings to Britain in 1890. This was followed by the building of the Kenya–Uganda railway passing through the country.[46]

The building of the railway was resisted by some ethnic groups—notably the Nandi led by Orkoiyot Koitalel Arap Samoei for ten years from 1890 to 1900—however the British eventually built the railway. The Nandi were the first ethnic group to be put in a native reserve to stop them from disrupting the building of the railway.[46]

During the railway construction era, there was a significant inflow of Indian people, who provided the bulk of the skilled manpower required for construction.[47] They and most of their descendants later remained in Kenya and formed the core of several distinct Indian communities such as the Ismaili Muslim and Sikh communities.[48]

While building the railway through Tsavo, a number of the Indian railway workers and local African labourers were attacked by two lions known as the Tsavo maneaters.[49]

At the outbreak of World War I in August 1914, the governors of British East Africa (as the protectorate was generally known) and German East Africa agreed a truce in an attempt to keep the young colonies out of direct hostilities. Lt. Col. Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck took command of the German military forces, determined to tie down as many British resources as possible. Completely cut off from Germany, von Lettow conducted an effective guerrilla warfare campaign, living off the land, capturing British supplies, and remaining undefeated. He eventually surrendered in Northern Rhodesia (today Zambia) fourteen days after the Armistice was signed in 1918.[47]

The Kenya–Uganda Railway near Mombasa, about 1899.

To chase von Lettow, the British deployed the British Indian Army troops from India but needed large numbers of porters to overcome the formidable logistics of transporting supplies far into the interior on foot. The Carrier Corps was formed and ultimately mobilised over 400,000 Africans, contributing to their long-term politicisation.[47]

In 1920, the East Africa Protectorate was turned into a colony and renamed Kenya for its highest mountain.[46]

During the early part of the 20th century, the interior central highlands were settled by British and other European farmers, who became wealthy farming coffee and tea.[50] (One depiction of this period of change from one colonist's perspective is found in the memoir Out of Africa by Danish author Baroness Karen von Blixen-Finecke, published in 1937.) By the 1930s, approximately 30,000 white settlers lived in the area and gained a political voice because of their contribution to the market economy.[47]

The central highlands were already home to over a million members of the Kikuyu people, most of whom had no land claims in European terms and lived as itinerant farmers. To protect their interests, the settlers banned the growing of coffee, introduced a hut tax, and the landless were granted less and less land in exchange for their labour. A massive exodus to the cities ensued as their ability to provide a living from the land dwindled.[47] There were 80,000 white settlers living in Kenya in the 1950s.[51]

Throughout World War II, Kenya was an important source of manpower and agriculture for the United Kingdom. Kenya itself was the site of fighting between Allied forces and Italian troops in 1940–41 when Italian forces invaded. Wajir and Malindi were bombed as well.

In 1952, Princess Elizabeth and her husband Prince Philip were on holiday at the Treetops Hotel in Kenya when her father, King George VI, died in his sleep. The young princess cut short her trip and returned home immediately to take her throne. She was crowned Queen Elizabeth II at Westminster Abbey in 1953 and as British hunter and conservationist Jim Corbett (who accompanied the royal couple) put it, she went up a tree in Africa a princess and came down a queen.[52]

Mau Mau Uprising (1952–1959)

A statue of Dedan Kimathi, a Kenyan rebel leader with the Mau Mau who fought against the British colonial system in the 1950s.

From October 1952 to December 1959, Kenya was in a state of emergency arising from the Mau Mau rebellion against British rule. The Mau Mau, also known as the Kenya Land and Freedom Army, were primarily members of the Kikuyu Group.

The governor requested and obtained British and African troops, including the King's African Rifles. The British began counter-insurgency operations. In May 1953, General Sir George Erskine took charge as commander-in-chief of the colony's armed forces, with the personal backing of Winston Churchill.[53]

The capture of Warũhiũ Itote (also known as General China) on 15 January 1954 and the subsequent interrogation led to a better understanding of the Mau Mau command structure. Operation Anvil opened on 24 April 1954, after weeks of planning by the army with the approval of the War Council. The operation effectively placed Nairobi under military siege. Nairobi's occupants were screened and the Mau Mau supporters moved to detention camps. The Home Guard formed the core of the government's strategy as it was composed of loyalist Africans, not foreign forces such as the British Army and King's African Rifles. By the end of the emergency, the Home Guard had killed 4,686 Mau Mau, amounting to 42% of the total insurgents.

The capture of Dedan Kimathi on 21 October 1956 in Nyeri signified the ultimate defeat of the Mau Mau and essentially ended the military offensive.[53] During this period, substantial governmental changes to land tenure occurred. The most important of these was the Swynnerton Plan, which was used to both reward loyalists and punish Mau Mau.

Independent Kenya (1963)

The first President and founding father of Kenya, Jomo Kenyatta.

The first direct elections for native Kenyans to the Legislative Council took place in 1957. Despite British hopes of handing power to "moderate" local rivals, it was the Kenya African National Union (KANU) of Jomo Kenyatta that formed a government. The Colony of Kenya and the Protectorate of Kenya each came to an end on 12 December 1963 with independence being conferred on all of Kenya. The United Kingdom ceded sovereignty over the Colony of Kenya. The Sultan of Zanzibar agreed that simultaneous with independence for the Colony of Kenya, the Sultan would cease to have sovereignty over the Protectorate of Kenya so that all of Kenya would be one sovereign, independent state.[54][55] In this way, Kenya became an independent country under the Kenya Independence Act 1963 of the United Kingdom. Exactly 12 months later on 12 December 1964, Kenya became a republic under the name "Republic of Kenya".[54]

Concurrently, the Kenyan army fought the Shifta War against ethnic Somali rebels inhabiting the Northern Frontier District, who wanted to join their kin in the Somali Republic to the north.[56] A cease fire was eventually reached with the signature of the Arusha Memorandum in October 1967, but relative insecurity prevailed through 1969.[57][58] To discourage further invasions, Kenya signed a defence pact with Ethiopia in 1969, which is still in effect.[59]

On 12 December 1964 the Republic of Kenya was proclaimed, and Jomo Kenyatta became Kenya's first president.[60]

Moi era (1978–2002)

At Kenyatta's death in 1978, Daniel arap Moi became President. Daniel arap Moi retained the Presidency, being unopposed in elections held in 1979, 1983 (snap elections) and 1988, all of which were held under the single party constitution. The 1983 elections were held a year early, and were a direct result of an abortive military coup attempt on 2 August 1982.

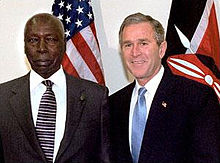

Daniel arap Moi, Kenya's second President, and George W. Bush, 2001

The abortive coup was masterminded by a low ranked Air Force serviceman, Senior Private Hezekiah Ochuka, and was staged mainly by enlisted men in the Air Force. The putsch was quickly suppressed by forces commanded by Chief of General Staff Mahamoud Mohamed, a veteran Somali military official.[61] They included the General Service Unit (GSU)—a paramilitary wing of the police—and later the regular police.

On the heels of the Garissa Massacre of 1980, Kenyan troops committed the Wagalla massacre in 1984 against thousands of civilians in Wajir County. An official probe into the atrocities was later ordered in 2011.[62]

The election held in 1988 saw the advent of the mlolongo (queuing) system, where voters were supposed to line up behind their favoured candidates instead of a secret ballot.[63] This was seen as the climax of a very undemocratic regime and it led to widespread agitation for constitutional reform. Several contentious clauses, including one that allowed for only one political party, were changed in the following years.[64] In democratic, multiparty elections in 1992 and 1997, Daniel arap Moi won re-election.[65]

2000s

View of Kibera, the largest urban slum in Africa

In 2002, Moi was constitutionally barred from running, and Mwai Kibaki, running for the opposition coalition "National Rainbow Coalition" (NARC), was elected President. Anderson (2003) reports the elections were judged free and fair by local and international observers, and seemed to mark a turning point in Kenya's democratic evolution.[65]

In 2005, Kenyans rejected a plan to replace the 1963 independence constitution with a new one.[66]

The toll of the 2007 Post-election violence included approximately 1,500 deaths and up to 600,000 people left internally displaced.[67]

In mid-2011, two consecutive missed rainy seasons precipitated the worst drought in East Africa seen in 60 years. The northwestern Turkana region was especially affected,[68] with local schools shut down as a result.[69] The crisis was reportedly over by early 2012 because of coordinated relief efforts. Aid agencies subsequently shifted their emphasis to recovery initiatives, including digging irrigation canals and distributing plant seeds.[70]

Geography and climate

A map of Kenya.

A Köppen climate classification map of Kenya.

At 580,367 km2 (224,081 sq mi),[2] Kenya is the world's forty-seventh largest country (after Madagascar). It lies between latitudes 5°N and 5°S, and longitudes 34° and 42°E. From the coast on the Indian Ocean, the low plains rise to central highlands. The highlands are bisected by the Great Rift Valley, with a fertile plateau lying to the east.[citation needed]

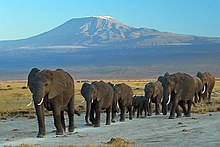

The Kenyan Highlands are one of the most successful agricultural production regions in Africa.[71] The highlands are the site of the highest point in Kenya and the second highest peak on the continent: Mount Kenya, which reaches 5,199 m (17,057 ft) and is the site of glaciers. Mount Kilimanjaro (5,895 m or 19,341 ft) can be seen from Kenya to the south of the Tanzanian border.

Climate

Kenya's climate varies from tropical along the coast to temperate inland to arid in the north and northeast parts of the country. The area receives a great deal of sunshine every month, and summer clothes are worn throughout the year. It is usually cool at night and early in the morning inland at higher elevations.

The "long rains" season occurs from March/April to May/June. The "short rains" season occurs from October to November/December. The rainfall is sometimes heavy and often falls in the afternoons and evenings. The temperature remains high throughout these months of tropical rain. The hottest period is February and March, leading into the season of the long rains, and the coldest is in July, until mid August.

A giraffe at Nairobi National Park, with Nairobi's skyline in background

| City | Elevation (m) | Max (°C) | Min (°C) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mombasa | Coastal town | 17 | 32.3 | 23.8 |

| Nairobi | Capital city | 1,661 | 25.2 | 13.6 |

| Kisumu | Lakeside city | 1,131 | 31.8 | 16.9 |

| Eldoret | Rift Valley town | 2,085 | 23.6 | 9.5 |

| Lodwar | Dry north plainlands | 506 | 34.8 | 23.7 |

| Mandera | Dry north plainlands | 506 | 34.8 | 25.7 |

Wildlife

Kenya has considerable land area devoted to wildlife habitats, including the Masai Mara, where blue wildebeest and other bovids participate in a large scale annual migration. More than 1 million wildebeest and 200,000 zebras participate in the migration across the Mara River.[72]

The "Big Five" game animals of Africa, that is the lion, leopard, buffalo, rhinoceros, and elephant, can be found in Kenya and in the Masai Mara in particular. A significant population of other wild animals, reptiles and birds can be found in the national parks and game reserves in the country. The annual animal migration occurs between June and September with millions of animals taking part, attracting valuable foreign tourism. Two million wildebeest migrate a distance of 2,900 kilometres (1,802 mi) from the Serengeti in neighbouring Tanzania to the Masai Mara[73] in Kenya, in a constant clockwise fashion, searching for food and water supplies. This Serengeti Migration of the wildebeest is a curious spectacle listed among the Seven Natural Wonders of Africa.

Government and politics

Kenya's third president Mwai Kibaki

Kenya is a presidential representative democratic republic. The president is both the head of state and head of government, and of a multi-party system. Executive power is exercised by the government. Legislative power is vested in both the government and the National Assembly and the Senate. The Judiciary is independent of the executive and the legislature. There was growing concern especially during former president Daniel arap Moi's tenure that the executive was increasingly meddling with the affairs of the judiciary.[74]

Kenya has a high degree of corruption according to Transparency International's Corruption Perception Index (CPI), a metric which attempts to gauge the prevalence of public sector corruption in various countries. In 2012, the nation placed 139th out of 176 total countries in the CPI, with a score of 27/100.[75] However, there are several rather significant developments with regards to curbing corruption from the Kenyan government, for instance, the establishment of a new and independent Ethics and Anti-Corruption Commission (EACC).[76]

The Supreme Court of Kenya building.

Following general elections held in 1997, the Constitution of Kenya Review Act designed to pave the way for more comprehensive amendments to the Kenyan constitution was passed by the national parliament.[77]

In December 2002, Kenyans held democratic and open elections, most of which were judged free and fair by international observers.[78] The 2002 elections marked an important turning point in Kenya's democratic evolution in that power was transferred peacefully from the Kenya African National Union (KANU), which had ruled the country since independence to the National Rainbow Coalition (NARC), a coalition of political parties.

Under the presidency of Mwai Kibaki, the new ruling coalition promised to focus its efforts on generating economic growth, combating corruption, improving education, and rewriting its constitution. A few of these promises have been met. There is free primary education.[79] In 2007, the government issued a statement declaring that from 2008, secondary education would be heavily subsidised, with the government footing all tuition fees.[80]

2013 elections and new government

Under the new constitution and with President Kibaki prohibited by term limits from running for a third term, Deputy Prime Minister Uhuru Kenyatta ran for office. He won with 50.51% of the vote in March 2013.

In December 2014, President Uhuru Kenyatta signed a Security Laws Amendment Bill, which supporters of the law suggested was necessary to guard against armed groups. Opposition politicians, human rights groups, and nine Western countries criticised the security bill, arguing that it infringed on democratic freedoms. The governments of the United States, the United Kingdom, Germany, and France also collectively issued a press statement cautioning about the law's potential impact. Through the Jubilee Coalition, the Bill was later passed on 19 December in the National Assembly under acrimonious circumstances.[81]

Foreign relations

President Barack Obama in Nairobi, July 2015

Kenya has close ties with its fellow Swahili-speaking neighbours in the African Great Lakes region. Relations with Uganda and Tanzania are generally strong, as the three nations work toward economic and social integration through common membership in the East African Community.

Relations with Somalia have historically been tense, although there has been some military co-ordination against Islamist insurgents. Kenya has good relations with the United Kingdom.[82] Kenya is one of the most pro-American nations in Africa, and the wider world.[83]

With International Criminal Court trial dates scheduled in 2013 for both President Kenyatta and Deputy President William Ruto related to the 2007 election aftermath, US president Barack Obama chose not to visit the country during his mid-2013 African trip.[84] Later in the summer, Kenyatta visited China at the invitation of President Xi Jinping after a stop in Russia and not having visited the United States as president.[85] In July 2015 Obama visited Kenya, the first American president to visit the country while in office.[86]

Armed forces

Kenyan Army Brig. Gen. Leonard Ngondi, left,[clarification needed] greets U.S. Marine Lt. Col. Steve Nichols, left, at Camp Lonestar in Kenya, 2006

The Kenya Defence Forces are the armed forces of the Republic of Kenya. The Kenya Army, Kenya Navy and Kenya Air Force compose the National Defence Forces. The current Kenya Defence Forces were established, and its composition laid out, in Article 241 of the 2010 Constitution of Kenya; the KDF is governed by the Kenya Defence Forces Act of 2012.[87] The President of Kenya is the commander-in-chief of all the armed forces.

The armed forces are regularly deployed in peacekeeping missions around the world. Further, in the aftermath of the national elections of December 2007 and the violence that subsequently engulfed the country, a commission of inquiry, the Waki Commission, commended its readiness and adjudged it to "have performed its duty well."[88] Nevertheless, there have been serious allegations of human rights violations, most recently while conducting counter-insurgency operations in the Mt Elgon area[89] and also in the district of Mandera central.[90]

Kenya's 47 counties.

Kenya's armed forces, like many government institutions in the country, have been tainted by corruption allegations. Because the operations of the armed forces have been traditionally cloaked by the ubiquitous blanket of "state security", the corruption has been hidden from public view, and thus less subject to public scrutiny and notoriety. This has changed recently. In what are by Kenyan standards unprecedented revelations, in 2010, credible claims of corruption were made with regard to recruitment [91] and procurement of Armoured Personnel Carriers.[92] Further, the wisdom and prudence of certain decisions of procurement have been publicly questioned.[93]

Administrative divisions

Kenya is divided into 47 semi-autonomous counties that are headed by governors. These 47 counties now form the first-order divisions of Kenya.

The smallest administrative units in Kenya are called locations. Locations often coincide with electoral wards. Locations are usually named after their central villages/towns. Many larger towns consist of several locations. Each location has a chief, appointed by the state.

Constituencies are an electoral subdivision, with each county comprising a whole number of constituencies. An Interim Boundaries commission was formed in year 2010 to review the constituencies and in its report, it recommended creation of an additional 80 constituencies. Previous to the 2013 elections, there were 210 constituencies in Kenya.[94]

Human rights

Homosexual acts are illegal in Kenya and punishable by up to 14 years in prison though the state often turns a blind eye on prosecuting homosexuals.[95][96] According to 2013 survey by the Pew Research Center, 90% of Kenyans believe that homosexuality should not be accepted by society.[97] While addressing a joint press conference together with President Barack Obama in 2015, President Kenyatta declined to assure Kenya's commitment to gay rights saying that "the issue of gay rights is really a non-issue." "But there are some things that we must admit we don't share. Our culture, our societies don't accept." [98]

In November 2008, WikiLeaks brought wide international attention[99] to The Cry of Blood report. In the report, the Kenya National Commission on Human Rights (KNCHR) reported these in their key finding "e)", stating that the forced disappearances and extrajudicial killings appeared to be official policy sanctioned by the political leadership, the Police.[100] The police often shoot suspected gangsters in public as a new "strategy" to fight the rising levels of crime in the country in total disregard of the laws.[101]

Economy

A proportional representation of Kenya's exports.

Kenya has a Human Development Index (HDI) of 0.555(medium), ranked 145 out of 186 in the world. As of 2005[update], 17.7% of Kenyans lived on less than $1.25 a day. [102] In 2017, Kenya ranked 92nd in the World Bank ease of doing business rating from 113rd in 2016 (of 190 countries).[103] The important agricultural sector is one of the least developed and largely inefficient, employing 75% of the workforce compared to less than 3% in the food secure developed countries. Kenya is usually classified as a frontier market or occasionally an emerging market, but it is not one of the least developed countries.

The economy has seen much expansion, seen by strong performance in tourism, higher education and telecommunications, and acceptable[neutrality is disputed] post-drought results in agriculture, especially the vital tea sector.[104] Kenya's economy grew by more than 7% in 2007, and its foreign debt was greatly reduced.[104] But this changed immediately after the disputed presidential election of December 2007, following the chaos which engulfed the country.

Telecommunication and financial activity over the last decade now comprises 62% of GDP. 22% of GDP still comes from the unreliable agricultural sector which employs 75% of the labour force (a consistent characteristic of under-developed economies that have not attained food security—an important catalyst of economic growth) A small portion of the population relies on food aid.[105] Industry and manufacturing is the smallest sector, accounting for 16% of GDP. The service, industry and manufacturing sectors only employ 25% of the labour force but contribute 75% of GDP.[104]

Kenya also exports textiles worth over $400million under Agoa.

Privatisation of state corporations like the defunct Kenya Post and Telecommunications Company, which resulted in East Africa's most profitable company—Safaricom, has led to their revival because of massive private investment.

As of May 2011[update], economic prospects are positive with 4–5% GDP growth expected, largely because of expansions in tourism, telecommunications, transport, construction and a recovery in agriculture. The World Bank estimated growth of 4.3% in 2012.[106]

Kenya, Trends in the Human Development Index 1970–2010.

In March 1996, the presidents of Kenya, Tanzania, and Uganda re-established the East African Community (EAC). The EAC's objectives include harmonising tariffs and customs regimes, free movement of people, and improving regional infrastructures. In March 2004, the three East African countries signed a Customs Union Agreement.

Kenya is East and Central Africa's hub for financial services. The Nairobi Securities Exchange (NSE) is ranked 4th in Africa in terms of market capitalisation. The Kenyan banking system is supervised by the Central Bank of Kenya (CBK). As of late July 2004, the system consisted of 43 commercial banks (down from 48 in 2001), several non-bank financial institutions, including mortgage companies, four savings and loan associations, and several core foreign-exchange bureaus.[104]

Tourism

Amboseli National Park

Tsavo East National Park

Tourism in Kenya is the second-largest source of foreign exchange revenue following agriculture.[107] The Kenya Tourism Board is responsible for maintaining information pertaining to tourism in Kenya.[108][109]

The main tourist attractions are photo safaris through the 60 national parks and game reserves. Other attractions include the wildebeest migration at the Masaai Mara which is considered the 7th wonder of the world, historical mosques and colonial-era forts at Mombasa, Malindi, and Lamu; the renowned vast scenery like the snow white capped Mount Kenya, the Great Rift Valley; the tea plantations at Kericho; the coffee plantations at Thika; a splendid view of Mt. Kilimanjaro across the border into Tanzania;[110] and the beaches along the Swahili Coast, in the Indian Ocean. Tourists, the largest number being from Germany and the United Kingdom, are attracted mainly to the coastal beaches and the game reserves, notably, the expansive East and Tsavo West National Park 20,808 square kilometres (8,034 sq mi) in the southeast.

Agriculture

A Tea farm near Kericho, Kericho County.

Agriculture is the second largest contributor to Kenya's gross domestic product (GDP), after the service sector. In 2005 agriculture, including forestry and fishing, accounted for 24% of GDP, as well as for 18% of wage employment and 50% of revenue from exports. The principal cash crops are tea, horticultural produce, and coffee. Horticultural produce and tea are the main growth sectors and the two most valuable of all of Kenya's exports. The production of major food staples such as corn is subject to sharp weather-related fluctuations. Production downturns periodically necessitate food aid—for example, in 2004 aid for 1.8 million people because of one of Kenya's intermittent droughts.[111]

A consortium led by the International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics (ICRISAT) has had some success in helping farmers grow new pigeon pea varieties, instead of maize, in particularly dry areas. Pigeon peas are very drought resistant, so can be grown in areas with less than 650 mm annual rainfall. Successive projects encouraged the commercialisation of legumes, by stimulating the growth of local seed production and agro-dealer networks for distribution and marketing. This work, which included linking producers to wholesalers, helped to increase local producer prices by 20–25% in Nairobi and Mombasa. The commercialisation of the pigeon pea is now enabling some farmers to buy assets, ranging from mobile phones to productive land and livestock, and is opening pathways for them to move out of poverty.[112]

Tea, coffee, sisal, pyrethrum, corn, and wheat are grown in the fertile highlands, one of the most successful agricultural production regions in Africa.[71] Livestock predominates in the semi-arid savanna to the north and east. Coconuts, pineapples, cashew nuts, cotton, sugarcane, sisal, and corn are grown in the lower-lying areas. Kenya has not attained the level of investment and efficiency in agriculture that can guarantee food security and coupled with resulting poverty (53% of the population lives below the poverty line), a significant portion of the population regularly starves and is heavily dependent on food aid.[105] Poor roads, an inadequate railway network, under-used water transport and expensive air transport have isolated mostly arid and semi-arid areas and farmers in other regions often leave food to rot in the fields because they cannot access markets. This was last seen in August and September 2011 prompting the Kenyans for Kenya initiative by the Red Cross.[113]

Agricultural countryside in Kenya

Kenya's irrigation sector is categorized into three organizational types: smallholder schemes, centrally-managed public schemes and private/commercial irrigation schemes.

The smallholder schemes are owned, developed and managed by individuals or groups of farmers operating as water users or self-help groups. Irrigation is carried out on individual or on group farms averaging 0.1–0.4 ha. There are about 3,000 smallholder irrigation schemes covering a total area of 47,000 ha.

The country has seven large, centrally managed irrigation schemes, namely Mwea, Bura, Hola, Perkera, West Kano, Bunyala and Ahero covering a total commanded area of 18,200 ha and averaging 2,600 ha per scheme. These schemes are managed by the National Irrigation Board and account for 18% of irrigated land area in Kenya.

Large-scale private commercial farms cover 45,000 hectares accounting for 40% of irrigated land. They utilize high technology and produce high-value crops for the export market, especially flowers and vegetables.[114]

Kenya is the world's 3rd largest exporter of cut flowers.[115] Roughly half of Kenya's 127 flower farms are concentrated around Lake Naivasha, 90 kilometers northwest of Nairobi.[115] To speed their export, Nairobi airport has a terminal dedicated to the transport of flowers and vegetables.[115]

Industry and manufacturing

The Kenya Commercial Bank headquarters at KENCOM House (right) in Nairobi.

Although Kenya is the most industrially developed country in the African Great Lakes region, manufacturing still accounts for only 14% of the GDP. Industrial activity, concentrated around the three largest urban centres, Nairobi, Mombasa and Kisumu, is dominated by food-processing industries such as grain milling, beer production, and sugarcane crushing, and the fabrication of consumer goods, e.g., vehicles from kits.

There is a cement production industry.[116] Kenya has an oil refinery that processes imported crude petroleum into petroleum products, mainly for the domestic market. In addition, a substantial and expanding informal sector commonly referred to as jua kali engages in small-scale manufacturing of household goods, auto parts, and farm implements.[117][118]

Kenya's inclusion among the beneficiaries of the US Government's African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA) has given a boost to manufacturing in recent years. Since AGOA took effect in 2000, Kenya's clothing sales to the United States increased from US$44 million to US$270 million (2006).[119] Other initiatives to strengthen manufacturing have been the new government's favourable tax measures, including the removal of duty on capital equipment and other raw materials.[120]

Transport

The country has an extensive network of paved and unpaved roads. Kenya's railway system links the nation's ports and major cities, connecting it with neighbouring Uganda. There are 15 airports which have paved runways.

Energy

The largest share of Kenya's electricity supply comes from geothermal energy[121] followed by hydroelectric stations at dams along the upper Tana River, as well as the Turkwel Gorge Dam in the west. A petroleum-fired plant on the coast, geothermal facilities at Olkaria (near Nairobi), and electricity imported from Uganda make up the rest of the supply. Kenya's installed capacity stood at 1,142 megawatts between 2001 and 2003. The state-owned Kenya Electricity Generating Company (KenGen), established in 1997 under the name of Kenya Power Company, handles the generation of electricity, while Kenya Power handles the electricity transmission and distribution system in the country. Shortfalls of electricity occur periodically, when drought reduces water flow. To become energy sufficient, Kenya aims to build a nuclear power plant by 2017.[122]

Workers at Olkaria Geothermal Power Plant

Kenya has proven deposits of oil in Turkana and the commercial viability was just discovered. Tullow Oil estimates Kenya's oil reserves to be around 10 billion barrels.[123] Exploration is still continuing to determine if there are more reserves. Kenya currently imports all crude petroleum requirements. Kenya, east Africa's largest economy, has no strategic reserves and relies solely on oil marketers' 21-day oil reserves required under industry regulations. Petroleum accounts for 20% to 25% of the national import bill.[124]

Overall Chinese investment and trade

Published comments on Kenya's Capital FM website by Liu Guangyuan, China's ambassador to Kenya, at the time of President Kenyatta's 2013 trip to Beijing, said, "Chinese investment in Kenya ... reached $474 million, representing Kenya's largest source of foreign direct investment, and ... bilateral trade ... reached $2.84 billion" in 2012. Kenyatta was "[a]ccompanied by 60 Kenyan business people [and hoped to] ... gain support from China for a planned $2.5 billion railway from the southern Kenyan port of Mombasa to neighboring Uganda, as well as a nearly $1.8 billion dam", according to a statement from the president's office also at the time of the trip.[85]

Base Titanium, a subsidiary of Base resources of Australia, shipped its first major consignment of minerals to China. About 25,000 tonnes of ilmenite was flagged off the Kenyan coastal town of Kilifi. The first shipment was expected to earn Kenya about Kshs15–20 billion in earnings.[125] Recently the Chinese contracted railway project from Nairobi to Mombasa was suspended due to dispute over compensation for land acquisition.[126]

Vision 2030

The official logo of Vision 2030.

In 2007, the Kenyan government unveiled Vision 2030, an economic development programme it hopes will put the country in the same league as the Asian Economic Tigers by the year 2030. In 2013, it launched a National Climate Change Action Plan, having acknowledged that omitting climate as a key development issue in Vision 2030 was an oversight. The 200-page Action Plan, developed with support from the Climate & Development Knowledge Network, sets out the Government of Kenya's vision for a 'low carbon climate resilient development pathway'. At the launch in March 2013, the Secretary of the Ministry of Planning, National Development and Vision 2030 emphasised that climate would be a central issue in the renewed Medium Term Plan that would be launched in the coming months. This would create a direct and robust delivery framework for the Action Plan and ensure climate change is treated as an economy-wide issue.[127]

| GDP | $41.84 billion (2012) at Market Price. $76.07 billion (Purchasing Power Parity, 2012) There exists an informal economy that is never counted as part of the official GDP figures. |

|---|---|

| Annual growth rate | 5.1% (2012) |

| Per capita income | Per Capita Income (PPP)= $1,800 |

| Agricultural produce | tea, coffee, corn, wheat, sugarcane, fruit, vegetables, dairy products, beef, pork, poultry, eggs |

| Industry | small-scale consumer goods (plastic, furniture, batteries, textiles, clothing, soap, cigarettes, flour), agricultural products, horticulture, oil refining; aluminium, steel, lead; cement, commercial ship repair, tourism |

| Exports | $5.942 billion | tea, coffee, horticultural products, petroleum products, cement, fish |

|---|---|---|

| Major markets | Uganda 9.9%, Tanzania 9.6%, Netherlands 8.4%, UK, 8.1%, US 6.2%, Egypt 4.9%, Democratic Republic of the Congo 4.2% (2012)[2] | |

| Imports | $14.39 billion | machinery and transportation equipment, petroleum products, motor vehicles, iron and steel, resins and plastics |

| Major suppliers | China 15.3%, India 13.8%, UAE 10.5%, Saudi Arabia 7.3%, South Africa 5.5%, Japan 4.0% (2012)[2] | |

Oil exploration

Lake Turkana borders Turkana County

Kenya has proven oil deposits in Turkana County. President Mwai Kibaki announced on 26 March 2012 that Tullow Oil, an Anglo-Irish oil exploration firm, had struck oil but its commercial viability and subsequent production would take about three years to confirm.[128]

Early in 2006 Chinese president Hu Jintao signed an oil exploration contract with Kenya, part of a series of deals designed to keep Africa's natural resources flowing to China's rapidly expanding economy.

The deal allowed for China's state-controlled offshore oil and gas company, CNOOC, to prospect for oil in Kenya, which is just beginning to drill its first exploratory wells on the borders of Sudan and Somalia and in coastal waters. There are formal estimates of the possible reserves of oil discovered.[129]

Child labour and prostitution

Maasai people. The Maasai live in both Kenya and Tanzania.

Child labour is common in Kenya. Most working children are active in agriculture.[130] In 2006, UNICEF estimated that up to 30% of girls in the coastal areas of Malindi, Mombasa, Kilifi, and Diani were subject to prostitution. Most of the prostitutes in Kenya are aged 9–18.[130] The Ministry of Gender and Child Affairs employed 400 child protection officers in 2009.[130] The causes of child labour include poverty, the lack of access to education and weak government institutions.[130] Kenya has ratified Convention No. 81 on labour inspection in industries and Convention No. 129 on labour inspection in agriculture.[131]

Child labour in Kenya

Microfinance in Kenya

24 institutions offer business loans on a large scale, specific agriculture loans, education loans, and for any other purpose loans. Additionally there are:

- emergency loans, which are more expensive in respect to interest rates, but are quickly available

- group loans for smaller groups (4–5 members) and larger groups (up to 30 members)

- women loans, which are also available to a group of women

Out of approximately 40 million Kenyans, about 14 million Kenyans are not able to receive financial service through formal loan application service and an additional 12 million Kenyans have no access to financial service institutions at all. Further, 1 million Kenyans are reliant on informal groups for receiving financial aid.[132]

Conditions for microfinance products

- Eligibility criteria: the general criteria might include gender as in the case for special women loans, to be at least 18 years old, to own a valid Kenyan ID, have a business, demonstrate the ability to repay the loan, and to be a customer of the institution.

Credit scoring: there is no advanced credit scoring system and the majority has not stated any official loan distribution system. However, some institutions require to have an existing business for at least 3 months, own a small amount of cash, provide the institution with a business plan or proposal, have at least one guarantor, or to attend group meetings or training. For group loans, almost half of the institutions require group members to guarantee for each other.

Interest rate: they are mostly calculated on a flat basis and some at a declining balance. More than 90% of the institutions require monthly interest payments. The average interest rate is 30–40% for loans up to 500,000 Kenyan Shilling. For loans above 500,000 Kenyan Shilling, interest rates go up to 71%.

Demographics

A Bantu Kikuyu woman in traditional attire

| Population[133] | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Million | ||

| 1950 | 6.1 | ||

| 2000 | 31.4 | ||

| 2016 | 48.5 | ||

Kenya had a population of approximately 48 million people in January 2017.[2] Kenya has a young population, with 73% of residents aged below 30 years because of rapid population growth;[134][135] from 2.9 million to 40 million inhabitants over the last century.[136]

Kenya's capital, Nairobi, is home to Kibera, one of the world's largest slums. The shanty town is believed to house between 170,000[137] and 1 million locals.[138] The UNHCR base in Dadaab in the north also currently houses around 500,000 people.[139]

Ethnic groups

A Nilotic Turkana woman wearing traditional neck beads

Kenya has a diverse population that includes most major ethnoracial and linguistic groups found in Africa. There are an estimated 47 different communities, with Bantus (67%) and Nilotes (30%) constituting the majority of local residents.[12]Cushitic groups also form a small ethnic minority, as do Arabs, Indians and Europeans.[12][140]

According to the Kenya National Bureau of Statistics (KNBS), Kenya has a total population of 38,610,097 inhabitants. The largest native ethnic groups are the Kikuyu (6,622,576), Luhya (5,338,666), Kalenjin (4,967,328), Luo (4,044,440), Kamba (3,893,157), Kisii (2,205,669), Mijikenda (1,960,574), Meru (1,658,108), Turkana (988,592), and Maasai (841,622). Foreign-rooted populations include Kenyan Arabs, Somalis, Asians and Europeans.[141]

Languages

Kenya's various ethnic groups typically speak their mother tongues within their own communities. The two official languages, English and Swahili, are used in varying degrees of fluency for communication with other populations. English is widely spoken in commerce, schooling and government.[142]Peri-urban and rural dwellers are less multilingual, with many in rural areas speaking only their native languages.[143]

British English is primarily used in Kenya. Additionally, a distinct local dialect, Kenyan English, is used by some communities and individuals in the country, and contains features unique to it that were derived from local Bantu languages, such as Kiswahili and Kikuyu.[144] It has been developing since colonisation and also contains certain elements of American English. Sheng is a Kiswahili-based cant spoken in some urban areas. Primarily consisting of a mixture of Kiswahili and English, it is an example of linguistic code-switching.[145]

There are a total of 69 languages spoken in Kenya. Most belong to two broad language families: Niger-Congo (Bantu branch) and Nilo-Saharan (Nilotic branch), spoken by the country's Bantu and Nilotic populations, respectively. The Cushitic and Arab ethnic minorities speak languages belonging to the separate Afroasiatic family, with the Indian and European residents speaking languages from the Indo-European family.[146]

Urban centres

Largest cities or towns in Kenya OpenData Kenya CIA Factbook | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Rank | Name | County | Pop. | Rank | Name | County | Pop. | ||

Nairobi  Mombasa | 1 | Nairobi | Nairobi | 3 375 000 | 11 | Naivasha | Nakuru | 181 966 |  Kisumu  Nakuru |

| 2 | Mombasa | Mombasa | 1 200 000 | 12 | Kitui | Kitui | 155 896 | ||

| 3 | Kisumu | Kisumu | 409 928 | 13 | Machakos | Machakos | 150 041 | ||

| 4 | Nakuru | Nakuru | 307 990 | 14 | Thika | Kiambu | 139 853 | ||

| 5 | Eldoret | Uasin Gishu | 289 380 | 15 | Athi River | Machakos | 139 380 | ||

| 6 | Kehancha | Migori | 256 086 | 16 | Karuri | Kiambu | 129 934 | ||

| 7 | Ruiru | Kiambu | 238 858 | 17 | Nyeri | Nyeri | 125 357 | ||

| 8 | Kikuyu | Kiambu | 233 231 | 18 | Kilifi | Kilifi | 122 899 | ||

| 9 | Kangundo-Tala | Machakos | 218 557 | 19 | Garissa | Garissa | 119 696 | ||

| 10 | Malindi | Kilifi | 207 253 | 20 | Vihiga | Vihiga | 118 696 | ||

Religion

Holy Ghost Roman Catholic cathedral in Mombasa.

Mosque in Mwingi

The majority of Kenyans are Christian (83%), of whom 47.7% are Protestant and 23.5% are Latin Rite Roman Catholic.[147] The Presbyterian Church of East Africa has 3 million followers in Kenya and surrounding countries.[148] There are smaller conservative Reformed churches, the Africa Evangelical Presbyterian Church,[149] the Independent Presbyterian Church in Kenya, and the Reformed Church of East Africa. Orthodox Christianity counts 621,200 adherents.[150] Kenya has the highest number of Quakers in the world, with around 133,000 members represented at the Quaker United Nations Office.[151] The only Jewish synagogue in the country is located in Nairobi.

Islam is the second largest religion, comprising 11.2% of the population. Sixty percent of Kenyan Muslims live in the Coastal Region, comprising 50% of the total population there, while the upper part of Kenya's Eastern Region is home to 10% of the country's Muslims, where they constitute the majority religious group.[152]Indigenous beliefs are practiced by 1.7% of the population, although many self-identifying Christians and Muslims maintain some traditional beliefs and customs. Nonreligious Kenyans make up 2.4% of the population.[147]

Kenya has one of Africa's largest Hindu populations (around 300,000), mostly of Indian origin. It also hosts among the largest number of adherents of the Baha'i Faith (430,000), about 1% of the population. There is also a small Buddhist community.

Health

Outpatient Department of AIC Kapsowar Hospital[153] in Kapsowar.

Kenya's private sector is one of the most advanced and dynamic in Sub-Saharan Africa. Private healthcare businesses and companies are the main health care providers in the country even for the nation's poorest people. The private health sector is larger and more easily accessible than both the public and the non-profit health sectors in terms of facilities and personnel. According to a World Bank report, nearly half of the poorest 20 percent of Kenyans use a private health facility when a child is sick.[154]

Private health facilities are largely preferred for their strong brands, value-addition and focused patient-centered care in contrast to the minimalist evidence-based care provided in public health facilities. Private health facilities are diverse and cater for all economic groups. Hospitals such as the Aga Khan Hospital and the Mombasa Hospital are comparable to many preferred hospitals in the developed world but are expensive and accessible only to the rich and the insured. Many affordable and low-cost private medical institutions and clinics exist and are easily accessible to ordinary and middle-class residents. All private medical facilities are subjected to regular supervisory and supportive visits from a joint multi-cadre team of health officials from the county government and national regulatory bodies and undergo additional supportive and quality assurance and improvement processes when they operate under a social franchise such as the joint government-donor funded Tunza Family Network.

The control of medical practice by laymen through limited liability companies, county governments and other artificial legal entities is widespread and largely tolerated unlike other countries where medical affairs are strictly handled by medically qualified administrators.[155]

The health sector and health facilities are not protected by any special laws and are prone to mismanagement with health workers frequently being subjected to verbal, emotional and physical attacks by patients and administrators alike.

The public health sector consists of community-based (level I) services which are run by community health workers, dispensaries (level II facilities) which are run by nurses, health centers (level III facilities) which are run by clinical officers, sub-county hospitals (level IV facilities) which may be run by a clinical officer or a medical officer, county hospitals (level V facilities) which may be run by a medical officer or a medical practitioner, and national referral hospitals (level VI facilities) which are run by fully qualified medical practitioners (consultants and sub-specialists).

Table showing different grades of clinical officers, medical officers and medical practitioners in Kenya's public service

Nurses are by far the largest group of front-line health care providers in all sectors followed by clinical officers, medical officers and medical practitioners. According to the Kenya National Bureau of Statistics, in 2011 there were 65,000 qualified nurses registered in the country; 8,600 clinical officers and 7,000 doctors for the population of 43 million people (These figures from official registers include those who have died or left the profession hence the actual number of these workers may be lower).[156]

Traditional healers (Herbalists, witch doctors and faith healers) are readily available, trusted and widely consulted as practitioners of first or last choice by both rural and urban dwellers.

Despite major achievements in the health sector, Kenya still faces many challenges. The life expectancy estimate has dropped to approximately 55 years in 2009—five years below 1990 levels.[157] The infant mortality rate is high at approximately 44 deaths per 1,000 children in 2012.[158] The WHO estimated in 2011 that only 42% of births were attended by a skilled health professional.[159]

Diseases of poverty directly correlate with a country's economic performance and wealth distribution: Half of Kenyans live below the poverty level. Preventable diseases like malaria, HIV/AIDS, pneumonia, diarrhoea and malnutrition are the biggest burden, major child-killers, and responsible for much morbidity; weak policies, corruption, inadequate health workers, weak management and poor leadership in the public health sector are largely to blame. According to 2009 estimates, HIV prevalence is about 6.3% of the adult population.[160] However, the 2011 UNAIDS Report suggests that the HIV epidemic may be improving in Kenya, as HIV prevalence is declining among young people (ages 15–24) and pregnant women.[161] Kenya had an estimated 15 million cases of malaria in 2006.[162]

Women

Kenyan women in Nairobi

The total fertility rate in Kenya is estimated to be 4.49 children per woman in 2012.[163] According to a 2008–09 survey by the Kenyan government, the total fertility rate was 4.6% and the contraception usage rate among married women was 46%.[164]Maternal mortality is high, partly because of female genital mutilation,[104] with about 27% of women having undergone it.[165]

This practice is however on the decline as the country becomes more modernised, and the practice was also banned in the country in 2011.[166]

Women were economically empowered before colonialization.

By colonial land alienation, women lost access and control of land.[167] They became more economically dependent on men.[168] A colonial order of gender emerged where the male dominated the female.

[169]

Median age at first marriage increases with increasing education.

[170]

Rape, defilement and battering are not always seen as serious crimes.

[171]

Reports of sexual assault are not always taken seriously.

[171]

Education

School children in a classroom.

An MSc student at Kenyatta University in Nairobi.

Children attend nursery school, or kindergarten in the private sector until they are five years old. This lasts one to three years (KG1, KG2 and KG3) and is financed privately because there has been no government policy regarding it until recently.[172]

Basic formal education starts at age six years and lasts 12 years consisting of eight years in primary school and four years in high school or secondary school. Primary school is free in public schools and those attending can join a vocational youth/village polytechnic or make their own arrangements for an apprenticeship program and learn a trade such as tailoring, carpentry, motor vehicle repair, brick-laying and masonry for about two years.[173]

Those who complete high school can join a polytechnic or other technical college and study for three years, or proceed directly to the university and study for four years. Graduates from the polytechnics and colleges can then join the workforce and later obtain a specialized higher diploma qualification after a further one to two years of training, or join the university—usually in the second or third year of their respective course. The higher diploma is accepted by many employers in place of a bachelor's degree and direct or accelerated admission to post-graduate studies is possible in some universities.

A Maasai girl at school.

Public universities in Kenya are highly commercialized institutions and only a small fraction of qualified high school graduates are admitted on limited government-sponsorship into programs of their choice. Most are admitted into the social sciences, which are cheap to run, or as self-sponsored students paying the full cost of their studies. Most qualified students who miss out opt for middle-level diploma programs in public or private universities, colleges, and polytechnics.

38.5 percent of the Kenyan adult population is illiterate.[174] There are very wide regional disparities; for example, Nairobi had the highest level of literacy, 87.1 per cent, compared to North Eastern Province, the lowest, at 8.0 per cent. Preschool, which targets children from age three to five, is an integral component of the education system and is a key requirement for admission to Standard One (First Grade). At the end of primary education, pupils sit the Kenya Certificate of Primary Education (KCPE), which determines those who proceed to secondary school or vocational training. The result of this examination is needed for placement at secondary school.[173]

Primary school is for students aged 6/7-13/14 years. For those who proceed to the secondary level, there is a national examination at the end of Form Four – the Kenya Certificate of Secondary Education (KCSE), which determines those proceeding to the universities, other professional training or employment. Students sit examinations in eight subjects of their choosing. However, English, Kiswahili and mathematics are compulsory subjects.

The Kenya Universities and Colleges Central Placement Service (KUCCPS), formerly the Joint Admissions Board (JAB), is responsible for selecting students joining the public universities. Other than the public schools, there are many private schools, mainly in urban areas. Similarly, there are a number of international schools catering to various overseas educational systems.

Despite its impressive commercial approach and interests in the country, Kenya's academia and higher education system is notoriously rigid and disconnected from the needs of the local labour market and is widely blamed for the high number of unemployable and "half-baked" university graduates who struggle to fit in the modern workplace.[175]

Culture

Kenyan boys and girls performing a traditional dance

Nation Media House which hosts the Nation Media Group

The culture of Kenya consists of multiple traditions. Kenya has no single prominent culture that identifies it. It instead consists of the various cultures of the country's different communities.

Notable populations include the Swahili on the coast, several other Bantu communities in the central and western regions, and Nilotic communities in the northwest. The Maasai culture is well known to tourism, despite constituting a relatively small part of Kenya's population. They are renowned for their elaborate upper body adornment and jewellery.

Additionally, Kenya has an extensive music, television and theater scene.

Media

Kenya has a number of media outlets that broadcast domestically and globally. They cover news, business, sports and entertainment.

Popular Kenyan newspapers include:

The Daily Nation; part of the Nation Media Group (NMG) (largest market share)- The Standard

- The Star

- The People

- East Africa Weekly

- Taifa Leo

Television stations based in Kenya include:

Kenya Broadcasting Corporation (KBC)- Citizen TV

Kenya Television Network (KTN)

NTV (part of the Nation Media Group (NMG))- Kiss Television

- K24 Television

- Kass-TV

All of these terrestrial channels are transmitted via a DVB T2 digital TV signal.

Literature

Kenyan author Ngũgĩ wa Thiong'o.

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong'o is one of the best known writers of Kenya. His novel, Weep Not, Child, is an illustration of life in Kenya during the British occupation. The story details the effects of the Mau Mau on the lives of Kenyans. Its combination of themes—colonialism, education, and love—helped to make it one of the best-known novels in Africa.

M.G. Vassanji's 2003 novel The In-Between World of Vikram Lall won the Giller Prize in 2003. It is the fictional memoir of a Kenyan of Indian heritage and his family as they adjust to the changing political climates in colonial and post-colonial Kenya.

Since 2003, the literary journal Kwani? has been publishing Kenyan contemporary literature. Additionally, Kenya has also been nurturing emerging versatile authors such as Paul Kipchumba (Kipwendui, Kibiwott) who demonstrate pan-African outlook (see Africa in China's 21st Century: In Search of a Strategy (2017).[176]

Music

Popular Kenyan musician Jua Cali.

Kenya has a diverse assortment of popular music forms, in addition to multiple types of folk music based on the variety over 40 regional languages.[177]

The drums are the most dominant instrument in popular Kenyan music. Drum beats are very complex and include both native rhythm and imported ones, especially the Congolese cavacha rhythm. Popular Kenyan music usually involves the interplay of multiple parts, and more recently, showy guitar solos as well. There are also a number of local hip-hop artists, including Jua Cali and afro-pop bands such as Sauti Sol.

Lyrics are most often in Kiswahili or English. There is also some emerging aspect of Lingala borrowed from Congolese musicians. Lyrics are also written in local languages. Urban radio generally only plays English music, though there also exist a number of vernacular radio stations.

Zilizopendwa is a genre of local urban music that was recorded in the 1960s, 70s and 80s by musicians such as Daudi Kabaka, Fadhili William and Sukuma Bin Ongaro, and is particularly revered and enjoyed by older people—having been popularised by the Kenya Broadcasting Corporation's Kiswahili service (formerly called Voice of Kenya or VOK).

The isukuti is a vigorous dance performed by the Luhya sub-tribes to the beat of a traditional drum called the Isukuti during many occasions such as the birth of a child, marriage and funerals. Other traditional dances include the Ohangla among the Luo, Nzele among the Mijikenda, Mugithi among the Kikuyu and Taarab among the Swahili.

Additionally, Kenya has a growing Christian gospel music scene. Prominent local gospel musicians include the Kenyan Boys Choir.

Benga music has been popular since the late 1960s, especially in the area around Lake Victoria. The word benga is occasionally used to refer to any kind of pop music. Bass, guitar and percussion are the usual instruments.

Sports

Jepkosgei Kipyego and Jepkemoi Cheruiyot at London 2012 Olympics 5,000 meters

Kenya is active in several sports, among them cricket, rallying, football, rugby union and boxing. The country is known chiefly for its dominance in middle-distance and long-distance athletics, having consistently produced Olympic and Commonwealth Games champions in various distance events, especially in 800 m, 1,500 m, 3,000 m steeplechase, 5,000 m, 10,000 m and the marathon. Kenyan athletes (particularly Kalenjin) continue to dominate the world of distance running, although competition from Morocco and Ethiopia has reduced this supremacy. Kenya's best-known athletes included the four-time women's Boston Marathon winner and two-time world champion Catherine Ndereba, 800m world record holder David Rudisha, former Marathon world record-holder Paul Tergat, and John Ngugi.

Kenya won several medals during the Beijing Olympics, six gold, four silver and four bronze, making it Africa's most successful nation in the 2008 Olympics. New athletes gained attention, such as Pamela Jelimo, the women's 800m gold medalist who went on to win the IAAF Golden League jackpot, and Samuel Wanjiru who won the men's marathon. Retired Olympic and Commonwealth Games champion Kipchoge Keino helped usher in Kenya's ongoing distance dynasty in the 1970s and was followed by Commonwealth Champion Henry Rono's spectacular string of world record performances. Lately, there has been controversy in Kenyan athletics circles, with the defection of a number of Kenyan athletes to represent other countries, chiefly Bahrain and Qatar.[178] The Kenyan Ministry of Sports has tried to stop the defections, but they have continued anyway, with Bernard Lagat the latest, choosing to represent the United States.[178] Most of these defections occur because of economic or financial factors.[179] Decisions by the Kenyan government to tax athletes' earnings may also be a reason for defection.[180] Some elite Kenyan runners who cannot qualify for their country's strong national team find it easier to qualify by running for other countries.[181]

Kenyan Olympic and world record holder in the 800 meters, David Rudisha.

Kenya has been a dominant force in women's volleyball within Africa, with both the clubs and the national team winning various continental championships in the past decade.[182][183] The women's team has competed at the Olympics and World Championships though without any notable success. Cricket is another popular sport, also ranking as the most successful team sport. Kenya has competed in the Cricket World Cup since 1996. They upset some of the world's best teams and reached the semi-finals of the 2003 tournament. They won the inaugural World Cricket League Division 1 hosted in Nairobi and participated in the World T20. They also participated in the ICC Cricket World Cup 2011. Their current captain is Rakep Patel.[184]

Kenya is represented by Lucas Onyango as a professional rugby league player who plays with Oldham R.L.F.C.. Besides the former European Super League team, he has played for Widnes Vikings and rugby union with Sale Sharks.[185] Rugby union is increasing in popularity, especially with the annual Safari Sevens tournament. The Kenya Sevens team ranked 9th in IRB Sevens World Series for the 2006 season. In 2016, the team beat Fiji at the Singapore Sevens finals, making Kenya the second African nation after South Africa to win a World Series championship.[186][187][188]Kenya was also a regional powerhouse in football. However, its dominance has been eroded by wrangles within the now defunct Kenya Football Federation,[189] leading to a suspension by FIFA which was lifted in March 2007.

In the motor rallying arena, Kenya is home to the world-famous Safari Rally, commonly acknowledged as one of the toughest rallies in the world.[190] It was a part of the World Rally Championship for many years until its exclusion after the 2002 event owing to financial difficulties. Some of the best rally drivers in the world have taken part in and won the rally, such as Björn Waldegård, Hannu Mikkola, Tommi Mäkinen, Shekhar Mehta, Carlos Sainz and Colin McRae. Although the rally still runs annually as part of the Africa rally championship, the organisers are hoping to be allowed to rejoin the World Rally championship in the next couple of years.

Nairobi has hosted several major continental sports events, including the FIBA Africa Championship 1993 where Kenya's national basketball team finished in the top four, its best performance to date.[191]

Cuisine

Ugali and sukuma wiki, staples of Kenyan cuisine

Kenyans generally have three meals in a day—breakfast in the morning (kiamsha kinywa), lunch in the afternoon (chakula cha mchana) and supper in the evening (chakula cha jioni or known simply as "chajio"). In between, they have the 10 o'clock tea (chai ya saa nne) and 4 p.m. tea (chai ya saa kumi). Breakfast is usually tea or porridge with bread, chapati, mahamri, boiled sweet potatoes or yams. Githeri is a common lunch time dish in many households while Ugali with vegetables, sour milk (Mursik), meat, fish or any other stew is generally eaten by much of the population for lunch or supper. Regional variations and dishes also exist.

In western Kenya: among the Luo, fish is a common dish; among the Kalenjin who dominate much of the Rift Valley Region, mursik—sour milk—is a major drink.