Western Roman Empire

Roman Empire Senatus Populusque Romanus Imperium Romanuma | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 395–476/480b | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Tremissis depicting Julius Nepos (r. 474–480), the de jure last emperor of the Western Court | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

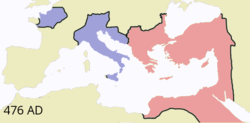

The territory controlled by the Western Roman Imperial court following the nominal division of the Roman Empire after the death of Emperor Theodosius I in A.D. 395. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Status | Western division of the Roman Empire a | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Capital | Mediolanum (395–402) Ravenna (402–476) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Common languages | Latin (official) Regional / local languages | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Religion | Roman religion until 4th century Christianity (state church) after 380 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Government | Autocracy | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Notable emperors | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

• 395–423 | Honorius | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

• 457–461 | Majorian | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

• 474–480 | Julius Nepos | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

• 475–476 | Romulus Augustulus | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Legislature | Roman Senate | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Historical era | Late antiquity | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

• Death of Emperor Theodosius I | 17 January 395 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

• Deposition of Emperor Romulus Augustulus | 4 September 476 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

• Murder of Emperor Julius Nepos | 25 April 480 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 395[1] | 2,000,000 km2 (770,000 sq mi) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Currency | Roman currency | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Today part of | Various countries

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

In historiography, the Western Roman Empire refers to the western provinces of the Roman Empire at any time during which they were administered by a separate independent Imperial court; in particular, this term is used to describe the period from 395 to 476, where there were separate coequal courts dividing the governance of the empire in the Western and the Eastern provinces, with a distinct imperial succession in the separate courts. The terms Western Roman Empire and Eastern Roman Empire are modern descriptions that describe political entities that were de facto independent; contemporary Romans did not consider the Empire to have been split into two separate empires but viewed it as a single polity governed by two separate imperial courts as an administrative expediency. The Western Roman Empire collapsed in 476, and the Western imperial court was formally dissolved in 480. The Eastern imperial court survived until 1453.

Though the Empire had seen periods with more than one Emperor ruling jointly before, the view that it was impossible for a single emperor to govern the entire Empire was institutionalised to reforms to Roman law by emperor Diocletian following the disastrous civil wars and disintegrations of the Crisis of the Third Century. He introduced the system of the tetrarchy in 286 CE, with two separate senior emperors titled Augustus, one in the East and one in the West, each with an appointed Caesar (junior emperor and designated successor). Though the tetrarchic system would collapse in a matter of years, the East–West administrative division would endure in one form or another over the coming centuries. As such, the Western Roman Empire would exist intermittently in several periods between the 3rd and 5th centuries. Some emperors, such as Constantine I and Theodosius I, governed as sole Augustus across the Roman Empire. On the death of Theodosius I in 395, he divided the empire between his two sons, with Honorius as his successor in the West, governing from Mediolanum, and Arcadius as his successor in the East, governing from Constantinople.

In 476, after the Battle of Ravenna, the Roman Army in the West suffered defeat at the hands of Odoacer and his Germanic foederati. Odoacer forced the deposition of emperor Romulus Augustulus and became the first King of Italy. In 480, following the assassination of the previous Western emperor Julius Nepos, the Eastern emperor Zeno dissolved the Western court and proclaimed himself the sole emperor of the Roman Empire. The date of 476 was popularized by the 18th century British historian Edward Gibbon as a demarcating event for the end of the Western Empire and is sometimes used to mark the transition from Antiquity to the Middle Ages. Odoacer's Italy, and other barbarian kingdoms, would maintain a pretence of Roman continuity through the continued use of the old Roman administrative systems and nominal subservience to the Eastern Roman court.

In the 6th century, emperor Justinian I re-imposed direct Imperial rule on large parts of the former Western Roman Empire, including the prosperous regions of North Africa, the ancient Roman heartland of Italy and parts of Hispania. Political instability in the Eastern heartlands, combined with foreign invasions and religious differences, made efforts to retain control of these territories difficult and they were gradually lost for good. Though the Eastern Empire retained territories in the south of Italy until the eleventh century, the influence that the Empire had over Western Europe had diminished significantly. The papal coronation of the Frankish King Charlemagne as Roman Emperor in 800 marked a new imperial line that would evolve into the Holy Roman Empire, which presented a revival of the Imperial title in Western Europe but was in no meaningful sense an extension of Roman traditions or institutions. The Great Schism of 1054 between the churches of Rome and Constantinople further diminished any authority the Emperor in Constantinople could hope to exert in the west.

Contents

1 Background

1.1 Rebellions and political developments

1.2 Crisis of the Third Century

1.3 Tetrarchy

1.4 Further divisions

2 History

2.1 Reign of Honorius

2.2 Escalating barbarian conflicts

2.3 Internal unrest and Majorian

2.4 Collapse

2.5 Fall of the Empire

3 Political aftermath

3.1 Germanic Italy

3.2 Barbarian Kingdoms

3.3 Imperial reconquest

4 Economic decline

5 Legacy

5.1 Nomenclature

5.2 Attempted restorations of a Western court

5.3 Later claims to the Imperial title in the West

6 List of Western Roman Emperors

6.1 Tetrarchy (286–313)

6.2 Constantinian dynasty (309–363)

6.3 Non-dynastic (363–364)

6.4 Valentinian dynasty (364–392)

6.5 Theodosian dynasty (392–455)

6.6 Non-dynastic (455–480)

7 See also

8 References

8.1 Citations

8.2 Bibliography

8.2.1 Websites

9 Further reading

10 External links

Background

As the Roman Republic expanded, it reached a point where the central government in Rome could not effectively rule the distant provinces. Communications and transportation were especially problematic given the vast extent of the Empire. News of invasion, revolt, natural disasters, or epidemic outbreak was carried by ship or mounted postal service, often requiring much time to reach Rome and for Rome's orders to be returned and acted upon. Therefore, provincial governors had de facto autonomy in the name of the Roman Republic. Governors had several duties, including the command of armies, handling the taxes of the province and serving as the province's chief judges.[2]

Prior to the establishment of the Empire, the territories of the Roman Republic had been divided in 43 BC among the members of the Second Triumvirate: Mark Antony, Octavian and Marcus Aemilius Lepidus. Antony received the provinces in the East: Achaea, Macedonia and Epirus (roughly modern Greece, Albania and the coast of Croatia), Bithynia, Pontus and Asia (roughly modern Turkey), Syria, Cyprus, and Cyrenaica.[3] These lands had previously been conquered by Alexander the Great; thus, much of the aristocracy was of Greek origin. The whole region, especially the major cities, had been largely assimilated into Greek culture, Greek often serving as the lingua franca.[4]

The Roman Republic before the conquests of Octavian

Octavian obtained the Roman provinces of the West: Italia (modern Italy), Gaul (modern France), Gallia Belgica (parts of modern Belgium, the Netherlands and Luxembourg), and Hispania (modern Spain and Portugal).[3] These lands also included Greek and Carthaginian colonies in the coastal areas, though Celtic tribes such as Gauls and Celtiberians were culturally dominant. Lepidus received the minor province of Africa (roughly modern Tunisia). Octavian soon took Africa from Lepidus, while adding Sicilia (modern Sicily) to his holdings.[5]

Upon the defeat of Mark Antony, a victorious Octavian controlled a united Roman Empire. The Empire featured many distinct cultures, all experienced a gradual Romanization.[6] While the predominantly Greek culture of the East and the predominantly Latin culture of the West functioned effectively as an integrated whole, political and military developments would ultimately realign the Empire along those cultural and linguistic lines. More often than not, Greek and Latin practices (and to some extent the languages themselves) would be combined in fields such as history (e.g., those by Cato the Elder), philosophy and rhetoric.[7][8][9]

Rebellions and political developments

Minor rebellions and uprisings were fairly common events throughout the Empire. Conquered tribes or oppressed cities would revolt, and the legions would be detached to crush the rebellion. While this process was simple in peacetime, it could be considerably more complicated in wartime. In a full-blown military campaign, the legions were far more numerous—as, for example, those led by Vespasian in the Great Jewish Revolt. To ensure a commander's loyalty, a pragmatic emperor might hold some members of the general's family hostage. To this end, Nero effectively held Domitian and Quintus Petillius Cerialis, Governor of Ostia, who were respectively the younger son and brother-in-law of Vespasian. Nero's rule was ended by a revolt of the Praetorian Guard, who had been bribed in the name of Galba. The Praetorian Guard, a figurative "sword of Damocles", was often perceived as being of dubious loyalty, primarily due its role in court intrigues and in overthrowing several emperors, including Pertinax and Aurelian.[10][11] Following their example, the legions at the borders increasingly participated in civil wars. For instance, legions stationed in Egypt and the eastern provinces would see significant participation in the civil war of 218 between Emperor Macrinus and Elagabalus.[12]

As the Empire expanded, two key frontiers revealed themselves. In the West, behind the rivers Rhine and Danube, Germanic tribes were an important enemy. Augustus, the first emperor, had tried to conquer them but had pulled back after the disastrous Battle of the Teutoburg Forest.[13] Whilst the Germanic tribes were formidable foes, the Parthian Empire in the East presented the greatest threat to the Empire. The Parthians were too remote and powerful to be conquered and there was a constant Parthian threat of invasion. The Parthians repelled several Roman invasions, and even after successful wars of conquest, such as those implemented by Trajan or Septimius Severus, the conquered territories were forsaken in attempts to ensure a lasting peace with the Parthians. The Parthian Empire would be succeeded by the Sasanian Empire, which continued hostilities with the Roman Empire.[14]

Controlling the western border of Rome was reasonably easy because it was relatively close to Rome itself and also because of the disunity among the Germans. However, controlling both frontiers simultaneously during wartime was difficult. If the emperor was near the border in the East, the chances were high that an ambitious general would rebel in the West and vice versa. This wartime opportunism plagued many ruling emperors and indeed paved the road to power for several future emperors. By the time of the Crisis of the Third Century, usurpation became a common method of succession: Philip the Arab, Trebonianus Gallus and Aemilianus were all usurping generals-turned-emperors whose rule would end with usurpation by another powerful general.[15][16][17]

Crisis of the Third Century

The Roman, Gallic and Palmyrene Empires in 271 AD.

With the assassination of the Emperor Alexander Severus on 18 March 235, the Roman Empire sank into a 50-year period of civil war, now known as the Crisis of the Third Century. The rise of the bellicose Sasanian Empire in place of Parthia posed a major threat to Rome in the east, as demonstrated by Shapur I's capture of Emperor Valerian in 259. Valerian's eldest son and heir-apparent, Gallienus, succeeded him and took up the fight on the eastern frontier. Gallienus' son, Saloninus, and the Praetorian Prefect Silvanus were residing in Colonia Agrippina (modern Cologne) to solidify the loyalty of the local legions. Nevertheless, Marcus Cassianius Latinius Postumus – the local governor of the German provinces – rebelled; his assault on Colonia Agrippina resulted in the deaths of Saloninus and the prefect. In the confusion that followed, an independent state known in modern historiography as the Gallic Empire emerged.[18]

Its capital was Augusta Treverorum (modern Trier), and it quickly expanded its control over the German and Gaulish provinces, all of Hispania and Britannia. It had its own senate, and a partial list of its consuls still survives. It maintained Roman religion, language, and culture, and was far more concerned with fighting the Germanic tribes, fending off Germanic incursions and restoring the security the Gallic provinces had enjoyed in the past, than in challenging the Roman central government.[19] However, in the reign of Claudius Gothicus (268 to 270), large expanses of the Gallic Empire were restored to Roman rule. At roughly the same time, several eastern provinces seceded to form the Palmyrene Empire, under the rule of Queen Zenobia.[20]

In 272, Emperor Aurelian finally managed to reclaim Palmyra and its territory for the empire. With the East secure, his attention turned to the West, invading the Gallic Empire a year later. Aurelian decisively defeated Tetricus I in the Battle of Châlons, and soon captured Tetricus and his son Tetricus II. Both Zenobia and the Tetrici were pardoned, although they were first paraded in a triumph.[21][22]

Tetrarchy

The organization of the Empire under the Tetrarchy

Diocletian was the first Emperor to divide the Roman Empire into a Tetrarchy. In 286 he elevated Maximian to the rank of augustus (emperor) and gave him control of the Western Empire.[23][24][25] In 293, Galerius and Constantius Chlorus were appointed as their subordinates (caesars), creating the First Tetrarchy. This system effectively divided the Empire into four major regions, as a way to avoid the civil unrest that had marked the 3rd century. In the West, Maximian made Mediolanum (now Milan) his capital, and Constantius made Trier his. In the East, Galerius made his capital Sirmium and Diocletian made Nicomedia his. On 1 May 305, Diocletian and Maximian abdicated, replaced by Galerius and Constantius, who appointed Maximinus II and Valerius Severus, respectively, as their caesars, creating the Second Tetrarchy.[26]

The Tetrarchy collapsed after the unexpected death of Constantius in 306. His son, Constantine the Great, was declared Western Emperor by the British legions,[27][28][29][30] but several other claimants arose and attempted to seize the Western Empire. In 308, Galerius held a meeting at Carnuntum, where he revived the Tetrarchy by dividing the Western Empire between Constantine and Licinius.[31] However, Constantine was more interested in conquering the whole empire than he was in the stability of the Tetrarchy, and by 314 began to compete against Licinius. Constantine defeated Licinius in 324, at the Battle of Chrysopolis, where Licinius was taken prisoner, and later murdered.[32] After Constantine unified the empire, he refounded the city of Byzantium in modern-day Turkey as Nova Roma ("New Rome"), later called Constantinople, and made it the capital of the Roman Empire.[33] The Tetrarchy was ended, although the concept of physically splitting the Roman Empire between two emperors remained. Although several powerful emperors unified both parts of the empire, this generally reverted in an empire divided into East and West upon their deaths, such as happened after the deaths of Constantine and Theodosius I.[34][35]

Further divisions

Division of the Roman Empire among the Caesars appointed by Constantine I: from west to east, the territories of Constantine II, Constans I, Dalmatius and Constantius II. After the death of Constantine I (May 337), this was the formal division of the Empire, until Dalmatius was killed and his territory divided between Constans and Constantius.

Constantius was born in 317 at Sirmium, Pannonia. He was the third son of Constantine the Great, the second by his second wife Fausta, the daughter of Maximian. Constantius was made Caesar by his father on 13 November 324.[36] The Roman Empire was under the rule of a single Emperor, but, with the death of Constantine in 337, the empire was partitioned between his surviving male heirs.[34] Constantius received the eastern provinces, including Constantinople, Thrace, Asia Minor, Syria, Egypt, and Cyrenaica; Constantine II received Britannia, Gaul, Hispania, and Mauretania; and Constans, initially under the supervision of Constantine II, received Italy, Africa, Illyricum, Pannonia, Macedonia, and Achaea. The provinces of Thrace, Achaea and Macedonia were shortly controlled by Dalmatius, nephew of Constantine I and a caesar, not an Augustus, until his murder by his own soldiers in 337.[37] The West was unified in 340 under Constans, who was assassinated in 350 under the order of the usurper Magnentius. After Magnentius lost the Battle of Mursa Major and committed suicide, a complete reunification of the whole Empire occurred under Constantius in 353.[36]

Constantius II focused most of his power in the East. Under his rule, the city of Byzantium – only recently re-founded as Constantinople – was fully developed as a capital. In 361, Constantius II became ill and died, and Constantius Chlorus' grandson Julian, who had served as Constantius II's Caesar, assumed power. Julian was killed in 363 in the Battle of Samarra against the Persian Empire and was succeeded by Jovian, who ruled for only nine months.[38]

The division of the Empire after the death of Theodosius I, c. 395 AD, superimposed on modern borders

Western Court under Honorius

Eastern Court under Arcadius

Following the death of Jovian, Valentinian I emerged as Emperor in 364. He immediately divided the Empire once again, giving the eastern half to his brother Valens. Stability was not achieved for long in either half, as the conflicts with outside forces (barbarian tribes) intensified. In 376, the Visigoths, fleeing before the Ostrogoths, who in turn were fleeing before the Huns, were allowed to cross the river Danube and settle in the Balkans by the Eastern government. Mistreatment caused a full-scale rebellion, and in 378 they inflicted a crippling defeat on the Eastern Roman field army in the Battle of Adrianople, in which Emperor Valens also died. The defeat at Adrianople was shocking to the Romans, and forced them to negotiate with and settle the Visigoths within the borders of the Empire, where they would become semi-independent foederati under their own leaders.[39]

More than in the East, there was also opposition to the Christianizing policy of the Emperors in the western part of the Empire. In 379, Valentinian I's son and successor Gratian declined to wear the mantle of Pontifex Maximus, and in 382 he rescinded the rights of pagan priests and removed the Altar of Victory from the Roman Curia, a decision which caused dissatisfaction among the traditionally pagan aristocracy of Rome.[40] Theodosius I later decreed the Edict of Thessalonica, which banned all religions except Christianity.[41]

The political situation was unstable. In 383, a powerful and popular general named Magnus Maximus seized power in the West and forced Gratian's half-brother Valentinian II to flee to the East for aid; in a destructive civil war the Eastern Emperor Theodosius I restored him to power.[42] In 392, the Frankish and pagan magister militum Arbogast assassinated Valentinian II and proclaimed an obscure senator named Eugenius as Emperor. In 394 the forces of the two halves of the Empire again clashed with great loss of life. Again Theodosius I won, and he briefly ruled a united Empire until his death in 395. He was the last Emperor to rule both parts of the Roman Empire before the West fragmented and collapsed.[35]

Theodosius I's older son Arcadius inherited the eastern half while the younger Honorius got the western half. Both were still minors and neither was capable of ruling effectively. Honorius was placed under the tutelage of the half-Roman/half-barbarian magister militum Flavius Stilicho,[43] while Rufinus became the power behind the throne in the east. Rufinus and Stilicho were rivals, and their disagreements would be exploited by the Gothic leader Alaric I who again rebelled in 408 following the massacre by Roman legions of thousands of barbarian families who were trying to assimilate into the Roman empire.[44]

Neither half of the Empire could raise forces sufficient even to subdue Alaric's men, and both tried to use Alaric against the other half. Alaric himself tried to establish a long-term territorial and official base, but was never able to do so. Stilicho tried to defend Italy and bring the invading Goths under control, but to do so he stripped the Rhine frontier of troops and the Vandals, Alans, and Suevi invaded Gaul in large numbers in 406. Stilicho became a victim of court intrigues and was killed in 408. While the East began a slow recovery and consolidation, the West began to collapse entirely. Alaric's men sacked Rome in 410.[45]

History

Reign of Honorius

Solidus of Emperor Honorius

Honorius, the younger son of Theodosius I, was declared Augustus (and as such co-emperor with his father) on January 23 in 393. Upon the death of Theodosius, Honorius inherited the throne of the West at the age of ten whilst his older brother Arcadius inherited the East. The western capital was initially Mediolanum, as it had been during previous divisions, but it was moved to Ravenna in 402 upon the entry of the Visigothic king Alaric I into Italy. Ravenna, protected by abundant marshes and strong fortifications, was far easier to defend but made it more difficult for the Roman military to defend the central parts of Italy from regular barbarian incursions.[46] Ravenna would remain the western capital 74 years until the deposition of Romulus Augustulus and would later be the capital of both the Ostrogothic Kingdom and the Exarchate of Ravenna.[47][48]

The reign of Honorius was, even by Western Roman standards, chaotic and plagued by both internal and external struggles. The Visigothic foederati under Alaric, magister militum in Illyricum, rebelled in 395. Gildo, the Comes Africae and Magister utriusque militiae per Africam, rebelled in 397 and initiated the Gildonic War. Stilicho managed to subdue Gildo but was campaigning in Raetia when the Visigoths entered Italy in 402.[49] Stilicho, hurrying back to aid in defending Italy, summoned legions in Gaul and Britain with which he managed to defeat Alaric twice before agreeing to allow him to retreat back to Illyria.[50]

Barbarian invasions and the invasion of usurper Constantine III in the Western Roman Empire during the reign of Honorius 407–409

The weakening of the frontiers in Britain and Gaul had dire consequences for the Empire. Numerous usurpers arose in Britain, including Marcus (406–407), Gratian (407), and Constantine III who invaded Gaul in 407. Britain was effectively abandoned by the empire by 410 due to the lack of resources and the need to look after more important frontiers. The weakening of the Rhine frontier allowed multiple barbarian tribes, including the Vandals, Alans and Suebi, to cross the river and enter Roman territory in 406.[51]

Honorius was convinced by the minister Olympius that Stilicho was conspiring to overthrow him, and so arrested and executed Stilicho in 408.[52] Olympius headed a conspiracy that successfully orchestrated the deaths of key individuals related to the faction of Stilicho, including his son and the families of many of his federated troops. This led many of the soldiers to instead join with Alaric, who returned to Italy in 409 and met little opposition. Despite attempts by Honorius to reach a settlement and six legions of Eastern Roman soldiers sent to support him,[53] the negotiations between Alaric and Honorius broke down in 410 and Alaric sacked the city of Rome. Though the sack was relatively mild and Rome was no longer the capital of even the Western Empire, the event shocked people across both halves of the Empire as this was the first time Rome (viewed at least as the symbolic heart of the Empire) had fallen to a foreign enemy since the Gallic invasions of the 4th century BC. The Eastern Roman Emperor Theodosius II, the successor of Arcadius, declared three days of mourning in Constantinople.[54]

Without Stilicho and following the sack of Rome, Honorius' reign grew more chaotic. The usurper Constantine III had stripped Roman Britain of its defenses when he crossed over to Gaul in 407, leaving the Romanized population subject to invasions, first by the Picts and then by the Saxons, Angli, and the Jutes who began to settle permanently from about 440 onwards. After Honorius accepted Constantine as co-emperor, Constantine's general in Hispania, Gerontius, proclaimed Maximus as Emperor. With the aid of general Constantius, Honorius successfully defeated Gerontius and Maximus in 411 and shortly thereafter captured and executed Constantine III. With Constantius back in Italy, the Gallo-Roman senator Jovinus revolted after proclaiming himself Emperor, with the support of the Gallic nobility and the barbarian Burgundians and Alans. Honorius turned to the Visigoths under King Ataulf for support.[55] Ataulf defeated and executed Jovinus and his proclaimed co-emperor Sebastianus in 413, around the same time as another usurper arose in Africa, Heraclianus. Heraclianus attempted to invade Italy but failed and retreated to Carthage, where he was killed.[56]

With the Roman legions withdrawn, northern Gaul became increasingly subject to Frankish influence, the Franks naturally adopting a leading role in the region. In 418, Honorius granted southwestern Gaul (Gallia Aquitania) to the Visigoths as a vassal federation. Honorius removed the local imperial governors, leaving the Visigoths and the provincial Roman inhabitants to conduct their own affairs. As such, the first of the "barbarian kingdoms", the Visigothic Kingdom, was formed.[57]

Escalating barbarian conflicts

Germanic and Hunnic invasions of the Roman Empire, 100–500 AD

Honorius' death in 423 was followed by turmoil until the Eastern Roman government installed Valentinian III as Western Emperor in Ravenna by force of arms, with Galla Placidia acting as regent during her son's minority. Theodosius II, the Eastern Emperor, had hesitated to announce the death of Honorius and in the ensuing interregnum, Joannes was nominated as Western Emperor. Joannes' "rule" was short and the forces of the East defeated and executed him in 425.[58]

After a violent struggle with several rivals, and against Placidia's wish, Aetius rose to the rank of magister militum. Aetius was able to stabilize the Western Empire's military situation somewhat, relying heavily on his Hunnic allies. With their help Aetius undertook extensive campaigns in Gaul, defeating the Visigoths in 437 and 438 but suffering a defeat himself in 439, ending the conflict in a status quo ante with a treaty.[59]

Meanwhile, pressure from the Visigoths and a rebellion by Bonifacius, the governor of Africa, induced the Vandals under King Gaiseric to cross from Spain to Tingitana in what is now Morocco in 429. They temporarily halted in Numidia in 435 before moving eastward. With Aetius occupied in Gaul, the Western Roman government could do nothing to prevent the Vandals conquering the wealthy African provinces, culminating in the fall of Carthage on 19 October 439 and the establishment of the Vandal Kingdom. By the 400s, Italy and Rome itself were dependent on the taxes and foodstuffs from these provinces, leading to an economic crisis. With Vandal fleets becoming an increasing danger to Roman sea trade and the coasts and islands of the western and central Mediterranean, Aetius coordinated a counterattack against the Vandals in 440, organizing a large army in Sicily.[60]

However, the plans for retaking Africa had to be abandoned due to the immediate need to combat the invading Huns, who in 444 were united under their ambitious king Attila. Turning against their former ally, the Huns became a formidable threat to the Empire. Aetius transferred his forces to the Danube,[60] though Attila concentrated on raiding the Eastern Roman provinces in the Balkans, providing temporary relief to the Western Empire. In 449, Attila received a message from Honoria, Valentinian III's sister, offering him half the western empire if he would rescue her from an unwanted marriage that her brother was forcing her into. With a pretext to invade the West, Attila secured peace with the Eastern court and crossed the Rhine in early 451.[61] With Attila wreaking havoc in Gaul, Aetius gathered a coalition of Roman and Germanic forces, including Visigoths and Burgundians, and prevented the Huns from taking the city of Aurelianum, forcing them into retreat.[62] At the Battle of the Catalaunian Plains, the Roman-Germanic coalition met and defeated the Hunnic forces, though Attila escaped.[63]

Attila regrouped and invaded Italy in 452. With Aetius not having enough forces to attack him, the road to Rome was open. Valentinian sent Pope Leo I and two leading senators to negotiate with Attila. This embassy, combined with a plague among Attila's troops, the threat of famine, and news that the Eastern Emperor Marcian had launched an attack on the Hun homelands along the Danube, forced Attila to turn back and leave Italy. When Attila died unexpectedly in 453, the power struggle that erupted between his sons ended the threat posed by the Huns.[64]

Internal unrest and Majorian

The Western Roman Empire during the reign of Majorian in 460 AD. During his four-year-long reign from 457 to 461, Majorian successfully restored Western Roman authority in Hispania and most of Gaul. Despite his accomplishments, Roman rule in the west would last less than two more decades.

Valentinian III was intimidated by Aetius and was encouraged by the Roman senator Petronius Maximus and the chamberlain Heraclius to assassinate him. When Aetius was at court in Ravenna delivering a financial account, Valentinian suddenly leaped from his seat and declared that he would no longer be the victim of Aetius' drunken depravities. Aetius attempted to defend himself from the charges, but Valentinian drew his sword and struck the weaponless Aetius on the head, killing him on the spot.[65] On March 16 the following year, Valentinian himself was killed by supporters of the dead general, possibly acting for Petronius Maximus. With the end of the Theodosian dynasty, Petronius Maximus proclaimed himself emperor during the ensuing period of unrest.[66]

Petronius was not able to take effective control of the significantly weakened and unstable Empire. He broke the betrothal between Huneric, son of the Vandal king Gaiseric, and Eudocia, daughter of Valentinian III. This was seen as a just cause of war by King Gaiseric, who set sail to attack Rome. Petronius and his supporters attempted to flee the city at the sight of the approaching Vandals, only to be stoned to death by a Roman mob. Petronius had reigned only 11 weeks.[67] With the Vandals at the gates, Pope Leo I requested that the King not destroy the ancient city or murder its inhabitants, to which Gaiseric agreed and the city gates were opened to him. Though keeping his promise, Gaiseric looted great amounts of treasure and damaged objects of cultural significance such as the Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus. The severity of the Vandal sack of 455 is disputed, though with the Vandals plundering the city for a full fourteen days as opposed to the Visigothic sack of 410, where the Visigoths only spent three days in the city, it was likely more thorough.[68]

Avitus, a prominent general under Petronius, was proclaimed emperor by the Visigothic king Theoderic II and accepted as such by the Roman Senate. Though supported by the Gallic provinces and the Visigoths, Avitus was resented in Italy due to ongoing food shortages caused by Vandal control of trade routes, and for using a Visigothic imperial guard. He disbanded his guard due to popular pressure, and the Suebian general Ricimer used the opportunity to depose Avitus, counting on popular discontent. After the deposition of Avitus, the Eastern Emperor Leo I did not select a new western Augustus. The prominent general Majorian defeated an invading force of Alemanni and was subsequently proclaimed Western Emperor by the army and eventually accepted as such by Leo.[69]

Majorian was the last Western Emperor to attempt to recover the Western Empire with his own military forces. To prepare, Majorian significantly strengthened the Western Roman army by recruiting large numbers of barbarian mercenaries, among them the Gepids, Ostrogoths, Rugii, Burgundians, Huns, Bastarnae, Suebi, Scythians and Alans, and built two fleets, one at Ravenna, to combat the strong Vandalic fleet. Majorian personally led the army to wage war in Gaul, leaving Ricimer in Italy. The Gallic provinces and the Visigothic Kingdom had rebelled following the deposition of Avitus, refusing to acknowledge Majorian as lawful emperor. At the Battle of Arelate, Majorian decisively defeated the Visigoths under Theoderic II and forced them to relinquish their great conquests in Hispania and return to foederati status. Majorian then entered the Rhone Valley, where he defeated the Burgundians and reconquered the rebel city of Lugdunum. With Gaul back under Roman control, Majorian turned his eyes to the Vandals and Africa. Not only did the Vandals pose a constant danger to coastal Italy and trade in the Mediterranean, but the province they ruled was economically vital to the survival of the West. Majorian began a campaign to fully reconquer Hispania to use it as a base for the reconquest of Africa. Throughout 459, Majorian campaigned against the Suebi in northwestern Hispania.[69]

The Vandals began to increasingly fear a Roman invasion. King Gaiseric tried to negotiate a peace with Majorian, who rejected the proposal. In the wake of this, Gaiseric devastated Mauretania, part of his own kingdom, fearing that the Roman army would land there. Having regained control of Hispania, Majorian intended to use his fleet at Carthaginiensis to attack the Vandals. Before he could, the fleet was destroyed, allegedly by traitors paid by the Vandals. Deprived of his fleet, Majorian had to cancel his attack on the Vandals and conclude a peace with Gaiseric. Disbanding his barbarian forces, Majorian intended to return to Rome and issue reforms, stopping at Arelate on his way. Here, Ricimer deposed and arrested him in 461, having gathered significant aristocratic opposition against Majorian. After five days of beatings and torture, Majorian was beheaded near the river Iria.[69]

Collapse

The Western and Eastern Roman Empire by 476

The final collapse of the Empire in the West was marked by increasingly ineffectual puppet Emperors dominated by their Germanic magister militums. The most pointed example of this is Ricimer, who effectively became a "shadow Emperor" following the depositions of Avitus and Majorian. Unable to take the throne for himself due to his barbarian heritage, Ricimer appointed a series of puppet Emperors who could do little to halt the collapse of Roman authority and the loss of the territories re-conquered by Majorian. The first of these puppet emperors, Libius Severus, had no recognition outside of Italy, with the Eastern Emperor Leo I and provincial governors in Gaul and Illyria all refusing to recognize him.

Severus died in 465 and Leo I, with the consent of Ricimer, appointed the capable Eastern general Anthemius as Western Emperor following an eighteen-month interregnum. The relationship between Anthemius and the East was good, Anthemius is the last Western Emperor recorded in an Eastern law, and the two courts conducted a joint operation to retake Africa from the Vandals, culminating in the disastrous Battle of Cap Bon in 468. In addition Anthemius conducted failed campaigns against the Visigoths, hoping to halt their expansion.[70]

The trial and subsequent execution of Romanus, an Italian senator and friend of Ricimer, on the grounds of treachery in 470 made Ricimer hostile to Anthemius. Following two years of ill feeling, Ricimer successfully deposed and killed Anthemius in 472, elevating Olybrius to the Western throne.[71] During the brief reign of Olybrius, Ricimer died and his nephew Gundobad succeeded him as magister militum. After only seven months of rule, Olybrius died of dropsy. Gundobad elevated Glycerius to Western Emperor. The Eastern Empire had rejected Olybrius and also rejected Glycerius, instead supporting a candidate of their own, Julius Nepos, magister militum in Dalmatia. With the support of Eastern Emperors Leo II and Zeno, Julius Nepos crossed the Adriatic Sea in the spring of 474 to depose Glycerius. At the arrival of Nepos in Italy, Glycerius abdicated without a fight and was allowed to live out his life as the Bishop of Salona.[72]

The brief rule of Nepos in Italy ended in 475 when Orestes, a former secretary of Attila and the magister militum of Julius Nepos, took control of Ravenna and forced Nepos to flee by ship to Dalmatia. Later in the same year, Orestes crowned his own young son as Western Emperor under the name Romulus Augustus. Romulus Augustus was not recognised as Western Emperor by the Eastern Court, who maintained that Nepos was the only legal Western Emperor, reigning in exile from Dalmatia.[73]

On September 4, 476, Odoacer, leader of the Germanic foederati in Italy, captured Ravenna, killed Orestes and deposed Romulus. Though Romulus was deposed, Nepos did not return to Italy and continued to reign as Western Emperor from Dalmatia, with support from Constantinople. Odoacer proclaimed himself ruler of Italy and began to negotiate with the Eastern Emperor Zeno. Zeno eventually granted Odoacer patrician status as recognition of his authority and accepted him as his viceroy of Italy. Zeno, however, insisted that Odoacer had to pay homage to Julius Nepos as the Emperor of the Western Empire. Odoacer accepted this condition and issued coins in the name of Julius Nepos throughout Italy. This, however, was mainly an empty political gesture, as Odoacer never returned any real power or territories to Nepos. The murder of Nepos in 480 prompted Odoacer to invade Dalmatia, annexing it to his Kingdom of Italy.[74]

Fall of the Empire

The city of Ravenna, Western Roman capital, on the Tabula Peutingeriana, a 13th-century medieval map possibly copied from a 4th- or 5th-century Roman original.

By convention, the Western Roman Empire is deemed to have ended on 4 September 476, when Odoacer deposed Romulus Augustus, but the historical record calls this determination into question. Indeed, the deposition of Romulus Augustus received very little attention in contemporary times. Romulus was a usurper in the eyes of the Eastern Roman Empire and the remaining territories of Western Roman control outside of Italy, with the previous emperor Julius Nepos still being alive and claiming to rule the Western Empire in Dalmatia. Furthermore, the Western court had lacked true power and had been subject to Germanic aristocrats for decades, with most of its legal territory being under control of various barbarian kingdoms. With Odoacer recognising Julius Nepos, and later the Eastern Emperor Zeno, as his sovereign, nominal Roman control continued in Italy.[75]Syagrius, who had managed to preserve Roman sovereignty in an exclave in northern Gaul (a realm today known as the Domain of Soissons) also recognized Nepos as his sovereign and the legitimate Western Emperor.[76]

The authority of Julius Nepos as Emperor was accepted not only by Odoacer in Italy, but by the Eastern Empire and Syagrius in Gaul (who had not recognized Romulus Augustulus). Nepos was murdered by his own soldiers in 480, a plot some attribute to Odoacer or the previous, deposed emperor Glycerius,[77] and the Eastern Emperor Zeno chose not to appoint a new western emperor. Zeno, recognizing that no true Roman control remained over the territories legally governed by the Western court, instead chose to abolish the juridical division of the position of Emperor and declared himself the sole emperor of the Roman Empire. Zeno became the first sole Roman emperor since the division after Theodosius I, 85 years prior, and the position would never again be divided. As such, the (eastern) Roman emperors after 480 are the successors of the western ones, albeit only in a juridical sense.[78] These emperors would continue to rule the Roman Empire until the Fall of Constantinople in 1453, nearly a thousand years later.[79] As 480 marks the end of the juridical division of the empire into two separate imperial courts, some historians refer to the death of Nepos and abolition of the Western Empire by Zeno as the end of the Western Roman Empire.[76][80]

Despite the fall, or abolition, of the Western Empire, many of the new Barbarian kings of western Europe continued to operate firmly within a Roman administrative framework. This is especially true in the case of the Ostrogoths, who came to rule Italy after Odoacer. They continued to use the administrative systems of Odoacer's kingdom, essentially those of the Western Roman Empire, and administrative positions continued to be staffed exclusively by Romans. The senate continued to function as it always had and the laws of the Empire were recognized as ruling the Roman population, though the Goths were ruled by their own traditional laws.[81] Western Roman administrative institutions, in particular those of Italy, thus continued to be used during "barbarian" rule and after the forces of the Eastern Roman empire re-conquered some of the formerly imperial territories. Some historians thus refer to the reorganizations of Italy and abolition of the old and separate Western Roman administrative units, such as the Praetorian prefecture of Italy, during the sixth century as the "true" fall of the Western Roman Empire.[75]

Roman cultural traditions continued throughout the territory of the Western Empire for long after its disappearance, and a recent school of interpretation argues that the great political changes can more accurately be described as a complex cultural transformation, rather than a fall.[82]

Political aftermath

Europe in 477 AD. Highlighted areas are Roman lands that survived the deposition of Romulus Augustulus.

Some territories under Roman control continued to exist in the West even after 480. The Domain of Soissons, a rump state in Northern Gaul ruled by Syagrius, survived until 486 when it was conquered by the Franks under King Clovis I after the Battle of Soissons. Syagrius was known as the "King of the Romans" by the Germanic peoples of the region and repeatedly claimed that he was merely governing a Roman province, not an independent realm.[76]

A Roman-Moor realm survived in the province of Mauretania Caesariensis until the early 8th century. An inscription on a fortification at the ruined city of Altava from the year 508 identifies a man named Masuna as the king of "Regnum Maurorum et Romanarum", the Kingdom of the Moors and Romans.[83] It is possible that Masuna is the same man as the "Massonas" who allied himself with the forces of the Eastern Roman Empire against the Vandals in 535.[84] As the Mauro-Roman realm shrank it eventually became known as the Kingdom of Altava after its capital city and it is believed that it fell during the Islamic conquests of the 700s. Alternatively, the kingdom may have been defeated by the Eastern Roman magister militum Gennadius in 578 and incorporated into the Empire once more.[85]

Germanic Italy

Odoacer's Italy in 480 AD, following the annexation of Dalmatia

The deposition of Romulus Augustus and the rise of Odoacer as ruler of Italy in 476 received very little attention at the time.[75] Overall, very little changed for the people; there was still a Roman Emperor in Constantinople to whom Odoacer had subordinated himself. Interregna had been experienced at many points in the West before and the deposition of Romulus Augustus was nothing out of the ordinary. Odoacer saw his rule as entirely in the tradition of the Roman Empire, not unlike Ricimer, and he effectively ruled as an imperial "governor" of Italy and was even awarded the title of patricius. Odoacer ruled using the Roman administrative systems already in place and continued to mint coins with the name and portrait of Julius Nepos until 480 and later with the name and portrait of the Eastern Augustus, rather than in his own name.[75]

When Nepos was murdered in Dalmatia in 480, Odoacer assumed the duty of pursuing and executing the assassins and established his own rule in Dalmatia at the same time.[86] Odoacer established his power with the loyal support of the Roman Senate, a legislative body that had continued even without an emperor residing in Italy. Indeed, the Senate seems to have increased in power under Odoacer. For the first time since the mid-3rd century, copper coins were issued with the legend S C (Senatus Consulto). These coins were copied by Vandals in Africa and also formed the basis of the currency reform carried out by Emperor Anastasius in the East.[87]

Solidus minted under Odoacer with the name and portrait of the Eastern Emperor Zeno

Under Odoacer, Western consuls continued to be appointed as they had been under the Western Roman Empire and were accepted by the Eastern Court, the first being Caecina Decius Maximus Basilus in 480. Basilus was made the praetorian prefect of Italy in 483, another traditional position which continued to exist under Odoacer.[88] Eleven further consuls were appointed by the Senate under Odoacer from 480 to 493 and one further Praetorian Prefect of Italy was appointed, Caecina Mavortius Basilius Decius (486–493).[89]

Though Odoacer ruled as a Roman governor would have and maintained himself as a subordinate to the remaining Empire, the Eastern Emperor Zeno began to increasingly see him as a rival. Thus, Zeno promised Theoderic the Great of the Ostrogoths, foederati of the Eastern Court, control over the Italian peninsula if he was able to defeat Odoacer.[90] Theoderic led the Ostrogoths across the Julian Alps and into Italy and defeated Odoacer in battle twice in 489. Following four years of hostilities between them, John, the Bishop of Ravenna, was able to negotiate a treaty in 493 between Odoacer and Theoderic whereby they agreed to rule Ravenna and Italy jointly. Theoderic entered Ravenna on 5 March and Odoacer was dead ten days later, killed by Theoderic after sharing a meal with him.[91]

Map of the realm of Theoderic the Great at its height in 523, following the annexation of the southern parts of the Burgundian kingdom. Theoderic ruled both the Visigothic and Ostrogothic kingdoms and exerted hegemony over the Burgundians and Vandals.

Theoderic inherited Odoacer's role as acting viceroy for Italy and ostensibly a patricius and subject of the emperor in Constantinople. This position was recognized by Emperor Anastasius in 497, four years after Theoderic had defeated Odoacer. Though Theodoric acted as an independent ruler, he meticulously preserved the outward appearance of his subordinate position. Theoderic continued to use the administrative systems of Odoacer's kingdom, essentially those of the Western Roman Empire, and administrative positions continued to be staffed exclusively by Romans. The senate continued to function as it always had and the laws of the Empire were recognized as ruling the Roman population, though the Goths were ruled by their own traditional laws. As a subordinate, Theoderic did not have the right to issue his own laws, only edicts or clarifications.[92] The army and military offices were exclusively staffed by the Goths, however, who largely settled in northern Italy.[93]

Though acting as a subordinate in domestic affairs, Theodoric acted increasingly independent in his foreign policies. Seeking to counterbalance the influence of the Empire in the East, Theoderic married his daughters to the Visigothic king Alaric II and the Burgundian prince Sigismund. His sister Amalfrida was married to the Vandal king Thrasamund and he married Audofleda, sister of the Frankish king Clovis I, himself.[94] Through these alliances and occasional conflicts, the territory controlled by Theoderic in the early sixth century nearly constituted a restored Western Roman Empire. Ruler of Italy since 493, Theoderic became king of the Visigoths in 511 and exerted hegemony over the Vandals in North Africa between 521 and 523. As such, his rule extended throughout the western Mediterranean. The Western imperial regalia, housed in Constantinople since the deposition of Romulus Augustulus in 476, were returned to Ravenna by Emperor Anastasius in 497.[95] Theoderic, by now Western Emperor in all but name, could not, however, assume an imperial title, not only because the notion of a separate Western court had been abolished but also due to his "barbarian" heritage, which, like that of Ricimer before him, would have barred him from assuming the throne.[70]

With the death of Theodoric in 526, his network of alliances began to collapse. The Visigoths regained autonomy under King Amalaric and the Ostrogoths' relations with the Vandals turned increasingly hostile under the reign of their new king Athalaric, a child under the regency of his mother Amalasuntha. Amalasuntha continued the policies of conciliation between the Goths and Romans, supporting the new Eastern Emperor Justinian I and allowing him to use Sicily as a staging point during the reconquest of Africa in the Vandalic War. With the death of Athalaric in 534, Amalasuntha crowned her cousin and only relative Theodahad as king, hoping for his support. Instead, Amalasuntha was imprisoned and, even though Theodahad assured Emperor Justinian of her safety, she was executed shortly after. This served as an ideal casus belli for Justinian, who prepared to invade and reclaim the Italian peninsula for the Roman Empire.[96]

Barbarian Kingdoms

Map of the Barbarian Kingdoms of the western Mediterranean in 526, seven years before the campaigns of reconquest under Justinian I

In the context of the Western Roman Empire, the term "barbarian kingdoms" most often refers to the Germanic kingdoms that sprang up in the former Western Roman territory. Their beginnings, together with the end of the Western Roman Empire, mark the transition from Late Antiquity to the Middle Ages. The practices of the barbarian kingdoms gradually replaced the old Roman institutions, specifically in the praetorian prefectures of Gaul and Italy, during the sixth and seventh centuries.[97]

6th-century Visigothic coin, struck in the name of Emperor Justinian I

There were several different kingdoms of differing size, power, and origins. The Visigothic Kingdom was the earliest established, founded as a vassal state to the Western Roman Empire through the Visigoths being granted land in southern Gaul by Emperor Honorius in 418.[57] After its establishment, relations between the Visigoths and the Western court were mixed. Though federated vassals, the Visigoths remained de facto independent and began a rapid period of expansion at the expense of the Western Empire. The Visigoths were thus periodically enemies with the Western court, though they had allied with the Western Roman army against the Huns and assisted in defeating Attila at the Battle of the Catalaunian Plains in 451. At the time of the collapse of the Western Empire in 476–480, the Visigoths controlled large areas of southern Gaul as well as a majority of Hispania. Their increased domain had been partly conquered and partly awarded to them by the Western Emperor Avitus in the 450s–60s.[98]

Like the Germanic kingdoms of Italy, the Visigoths continued to recognise the Emperor in Constantinople as a somewhat nominal sovereign, including minting coins in their names until the reign of Justinian I in the sixth century.[99] The Visigothic Kingdom continued to control most of the Iberian peninsula until it fell to the Umayyad Caliphate in the 720s.[100][101]

The Kingdom of Asturias was founded by a Visigoth nobleman around the same time and was the first Christian realm to be established in Iberia following the defeat of the Visigoths.[102] Asturias would be transformed into the Kingdom of León in 924,[103] which would develop into the predecessors of modern-day Spain.[104]

The Vandal Kingdom was founded through Vandal conquests in the provinces of Roman Africa, culminating in a siege and capture of Carthage in 439.[105] The Vandals continually used an impressive fleet to loot the coasts of both the Western and Eastern parts of the Empire, becoming an increasingly strong naval power. After the death of Attila, the Romans made repeated efforts to recapture Africa and destroy the Vandals, since they were in control of some of the richest ex-imperial lands. With several planned campaigns never being carried out or with the Imperial forces being destroyed in naval battles, the Vandals remained a power and even sacked Rome in 455.[106] Unlike the Visigoths, the Vandals minted their own coinage and were both de facto and de jure independent.[107] Like the Ostrogoths of Italy, the Vandalic Kingdom would be reconquered during the western campaigns of Emperor Justinian I.[108]

After the collapse of Theoderic the Great's control of the western Mediterranean, the Frankish Kingdom rose to become the most powerful of the barbarian kingdoms, having taken control of most of Gaul in the absence of Roman governance. Under Clovis I from the 480s to 511, the Franks would come to develop into a great regional power. They conquered the Domain of Soissons in 481, defeated the Alemanni in 504 and conquered all Visigothic territory north of the Pyrenees other than Septimania in 507. Relations between the Franks and the Eastern Empire appear to have been positive, with Emperor Anastasius granting Clovis the title of consul following his victory against the Visigoths. At the time of its dissolution in the 800s, the Frankish Kingdom had lasted far longer than the other migration period barbarian kingdoms. Its divided successors would develop into the medieval states of France (initially known as West Francia) and Germany (initially known as East Francia).[109]

Imperial reconquest

The Eastern Roman Empire, by reoccupying some of the former Western Roman Empire's lands, enlarged its territory considerably during Justinian's reign from 527 (red) to 565 (orange).

With Emperor Zeno having juridically reunified the Empire into one imperial court, the remaining Eastern Roman Empire continued to lay claim to the areas previously controlled by the Western court throughout Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages. Though military campaigns had been conducted by the Western court prior to 476 with the aim of recapturing lost territory, most notably under Majorian, the reconquests, if successful at all, were only momentary. It was as a result of the campaigns of the generals Belisarius and Narses on behalf of the Eastern Roman Emperor Justinian I from 533 to 554 that long-lasting reconquests of Roman lands were witnessed.[110]

During the 6th century, the Eastern Roman Empire under Justinian reconquered large areas of the former Western Roman Empire. With the pro-Roman Vandal king Hilderic having been deposed by Gelimer in 530,[111] Justinian prepared an expedition led by prominent general Belisarius. It swiftly retook North Africa between June 533 and March 534, returning the wealthy province to Roman rule. Following the reconquest, Justinian swiftly reintroduced the Roman administrations of the province, establishing a new Praetorian Prefecture of Africa and taking measures to decrease Vandal influence, eventually leading to the complete disappearance of the Vandalic people.[108]

@media all and (max-width:720px){.mw-parser-output .tmulti>.thumbinner{width:100%!important;max-width:none!important}.mw-parser-output .tmulti .tsingle{float:none!important;max-width:none!important;width:100%!important;text-align:center}}

Justinian I (left) was the first Eastern Emperor to attempt to reconquer the territories of the Western Roman Empire, undertaking successful campaigns in Africa and Italy in the 500s. Manuel I Komnenos (right) was the last, campaigning in southern Italy in the 1150s.

Following the execution of the pro-Roman Ostrogoth queen Amalasuntha and the refusal of Ostrogoth King Theodahad to renounce his control of Italy, Justinian ordered the expedition to move on to reconquer Italy, ancient heartland of the Empire. From 534 to 540, the Roman forces campaigned in Italy and captured Ravenna, the Ostrogothic and formerly Western Roman capital, in 540. The Gothic resistance revived under King Totila in 541. They were finally defeated following campaigns by the Roman general Narses, who also repelled invasions into Italy by the Franks and Alemanni, though some cities in northern Italy continued to hold out until the 560s. Justinian promulgated the Pragmatic Sanction to reorganize the governance of Italy and the province was returned to Roman rule. The end of the conflict saw Italy devastated and considerably depopulated, which, combined with the disastrous effects of the Plague of Justinian, made it difficult to retain over the following centuries.[112]

Justinian also undertook limited campaigns against the Visigoths, recovering portions of the southern coast of the Iberian peninsula. Here, the province of Spania would last until the 620s, when the Visigoths under King Suintila reconquered the south coast.[113] These regions remained under Roman control throughout the reign of Justinian. Three years after his death, the Lombards invaded Italy. The Lombards conquered large parts of the devastated peninsula in the late 500s, establishing the Lombard Kingdom. They were in constant conflict with the Exarchate of Ravenna, a polity established to replace the old Praetorian Prefecture of Italy and enforce Roman rule in Italy. The wealthiest parts of the province, including the cities of Rome and Ravenna, remained securely in Roman hands under the Exarchate throughout the seventh century.[114]

Map of the Eastern Roman Empire in 717 AD. Over the course of the seventh and eighth centuries, Islamic expansion had ended Roman rule in Africa and though some bastions of Roman rule remained, most of Italy was controlled by the Lombards.

Although other Eastern emperors occasionally attempted to campaign in the West, none were as successful as Justinian. After 600, events conspired to drive the Western provinces out of Constantinople's control, with imperial attention focused on the pressing issues of war with Sasanian Persia and then the rise of Islam. For a while, the West remained important, with Emperor Constans II ruling from Syracuse in Sicily a Roman Empire that still stretched from North Africa to the Caucasus in the 660s. Thereafter, imperial attention declined, with Constantinople itself being besieged in the 670s, renewed war with the Arabs in the 680s, and then a period of chaos between 695 and 717, during which time Africa was finally lost once and for all, being conquered by the Umayyad Caliphate. Through reforms and military campaigns, Emperor Leo III attempted to restore order in the Empire, but his doctrinal reforms, known as the Iconoclastic Controversy, were extremely unpopular in the West and were condemned by Pope Gregory III.[115]

This led to the final breakdown in imperial rule over Rome itself, and the gradual transition of the Exarchate of Ravenna into the independent Papal States, led by the Pope. In an attempt to gain support against the Lombards, the Pope called for aid from the Frankish Kingdom instead of the Eastern Empire, eventually crowning the Frankish king Charlemagne as "Roman Emperor" in 800 AD. Though this coronation was strongly opposed by the Eastern Empire, there was little they could do as their influence in Western Europe decreased. After a series of small wars in the 810s, Emperor Michael I recognized Charlemagne as an "Emperor". He refused to recognize him as a "Roman Emperor" (a title which Michael reserved for himself and his successors), instead recognizing him as the slightly less prestigious "Emperor of the Franks".[116]

Imperial rule continued in Sicily throughout the eighth century, with the island slowly being overrun by the Arabs during the course of the ninth century. In Italy, a few strongholds in Calabria provided a base for a later, modest imperial expansion, which reached its peak in the early eleventh century, with most of southern Italy under Roman rule of a sort. This, however, was undone by further civil wars in the Empire, and the slow conquest of the region by the Empire's former mercenaries, the Normans, who finally put an end to imperial rule in Western Europe in 1071 with the conquest of Bari.[117] The last Emperor to attempt reconquests in the West was Manuel I Komnenos, who invaded southern Italy during a war with the Norman Kingdom of Sicily in the 1150s. The city of Bari willingly opened its gates to the Emperor and after successes in taking other cities in the region,[118] Manuel dreamed of a restored Roman Empire and a union between the churches of Rome and Constantinople, separated since the schism of 1054. Despite initial successes and Papal support, the campaign was unsuccessful and Manuel was forced to return east.[119]

Economic decline

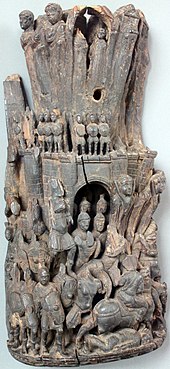

Stone-carved relief depicting the liberation of a besieged city by a relief force, with those defending the walls making a sortie. Western Roman Empire, early 5th century AD

The Western Roman Empire, less urbanized than the Eastern and more thinly populated, may have experienced an economic decline throughout the Late Empire in some provinces.[120] Southern Italy, northern Gaul (except for large towns and cities), and to some extent Spain and the Danubian areas may have suffered. The East fared better economically, especially as Emperors such as Constantine the Great and Constantius II had invested heavily in the eastern economy. As a result, the Eastern Empire could afford large numbers of professional soldiers and to augment them with mercenaries, while the Western Roman Empire could not afford this to the same extent. Even after major defeats, the East could, although not without difficulties, buy off its enemies with a ransom or "protection money".[121]

The political, economic and military control of the Eastern Empire's resources remained safe in Constantinople, which was well fortified and located at the crossroads of several major trade and military routes. The site of Constantinople, previously known as Byzantium, was acknowledged for its strategic importance by emperors Septimius Severus and Caracalla.[122]

In contrast, the Western Empire was more fragmented. Its capital was transferred to Ravenna in 402 largely for defensive reasons. Ravenna had easy access to the imperial fleet of the Eastern Empire but was isolated in other respects as it was surrounded by swamps and marshes. This isolation was intentional, as Ravenna had been chosen as capital due to being more defensible against the increasing barbarian incursions.[46]

Economic power remained focused on Rome and its hyper-rich senatorial aristocracy which dominated much of Italy and Africa in particular. After Gallienus banned senators from army commands in the mid-3rd century, the senatorial elite lost all experience of—and interest in—military life. In the early 5th century the wealthy landowning elite of the Roman Senate largely barred its tenants from military service, but it also refused to approve sufficient funding for maintaining a sufficiently powerful mercenary army to defend the entire Western Empire. The West's most important military area had been northern Gaul and the Rhine frontier in the 4th century, when Trier frequently served as the capital of the Empire. Many leading Western generals were barbarians.

After the civil war in 394 between Theodosius I and the usurper Eugenius, the new Western government installed by Theodosius I increasingly had to divert military resources from Britain and the Rhine to protect Italy. This, in turn, led to further rebellions and civil wars because the Western imperial government was not providing the military protection the northern provinces expected and needed against the barbarians.[123]

The Western Empire's resources were limited, and the lack of available manpower forced the government to rely ever more on confederate barbarian troops operating under their own commanders, who the Western Empire would often have difficulties paying. In certain cases, deals were struck with the leaders of barbaric mercenaries rewarding them with land, which led to the Empire's decline as less land meant there would be less tax revenue to support the military. As the central power weakened, the State gradually lost control of its borders and provinces, as well as control over the Mediterranean Sea. Roman Emperors tried to maintain control of the sea, but, once the Vandals conquered North Africa, imperial authorities had to cover too much ground with too few resources. The loss of the African provinces might have been the worse reversal on the West's fortunes, since they were among its wealthiest territories and supplied the essential grain imports to Italy. In many places, the Roman institutions collapsed along with the economic stability. In some regions, such as Gaul and Italy, the settlement of barbarians on former Roman lands seems to have caused relatively little disruption, with barbarian rulers using and modifying the Roman systems already in place.[124]

Legacy

On the left: Emperor Honorius on the consular diptych of Anicius Petronius Probus (406)

On the right: Consular diptych of Constantius III (a co-emperor with Honorius in 421), produced for his consulate in 413 or 417.

As the Western Roman Empire crumbled, the new Germanic rulers who conquered its constituent provinces maintained most Roman laws and traditions. Many of the invading Germanic tribes were already Christianized, although most were followers of Arianism. They quickly changed their adherence to the state church of the Roman Empire. This helped cement the loyalty of the local Roman populations, as well as the support of the powerful Bishop of Rome. Although they initially continued to recognize indigenous tribal laws, they were more influenced by Roman Law and gradually incorporated it.[97] Roman law, particularly the Corpus Juris Civilis collected on the orders of Justinian I, is the basis of modern civil law. In contrast, common law is based on Germanic Anglo-Saxon law. Civil law is by far the most widespread system of law in the world, in force in some form in about 150 countries.[125]

Romance languages, languages that developed from Latin following the collapse of the Western Roman Empire, are spoken in Western Europe to this day and their extent almost reflects the continental borders of the old Empire.

Latin as a language did not disappear. Vulgar Latin combined with neighboring Germanic and Celtic languages, giving rise to modern Romance languages such as Italian, French, Spanish, Portuguese, Romanian, and a large number of minor languages and dialects. Today, more than 900 million people are native speakers of Romance languages worldwide. In addition, many Romance languages are used as lingua francas by non-native speakers.[126]

Latin also influenced Germanic languages such as English and German.[127][128] It survives in a "purer" form as the language of the Catholic Church; the Catholic Mass was spoken exclusively in Latin until 1969). As such it was also used as a lingua franca by ecclesiasticals. It remained the language of medicine, law, and diplomacy (most treaties were written in Latin), as well as of intellectuals and scholarship, well into the 18th century. Since then the use of Latin has declined with the growth of other lingua francas, especially English and French.[129] The Latin alphabet was expanded due to the split of I into I and J, and of V into U, V, and, in places (especially Germanic languages and Polish), W. It is the most widely used alphabetic writing system in the world today. Roman numerals continue to be used in some fields and situations, though they have largely been replaced by Arabic numerals.[130]

A very visible legacy of the Western Roman Empire is the Catholic Church. Church institutions slowly began to replace Roman ones in the West, even helping to negotiate the safety of Rome during the late 5th century.[64] As Rome was invaded by Germanic tribes, many assimilated, and by the middle of the medieval period (c. 9th and 10th centuries) the central, western, and northern parts of Europe had been largely converted to Roman Catholicism and acknowledged the Pope as the Vicar of Christ. The first of the Barbarian kings to convert to the Church of Rome was Clovis I of the Franks; other kingdoms, such as the Visigoths, later followed suit to garner favor with the papacy.[131]

When Pope Leo III crowned Charlemagne as "Roman Emperor" in 800, he both severed ties with the outraged Eastern Empire and established the precedent that no man in Western Europe would be emperor without a papal coronation.[132] Although the power the Pope wielded changed significantly throughout the subsequent periods, the office itself has remained as the head of the Catholic Church and the head of state of the Vatican City. The Pope has consistently held the title of "Pontifex Maximus" since before the fall of the Western Roman Empire and retains it to this day; this title formerly used by the high priest of the Roman polytheistic religion, one of whom was Julius Caesar.[40][133]

The Roman Senate survived the initial collapse of the Western Roman Empire. Its authority increased under the rule of Odoacer and later the Ostrogoths, evident by the Senate in 498 managing to install Symmachus as pope despite both Theoderic of Italy and Emperor Anastasius supporting another candidate, Laurentius.[134] Exactly when the senate disappeared is unclear, but the institution is known to have survived at least into the 6th century, inasmuch as gifts from the senate were received by Emperor Tiberius II in 578 and 580. The traditional senate building, Curia Julia, was rebuilt into a church under Pope Honorius I in 630, probably with permission from the eastern emperor, Heraclius.[135]

Nomenclature

Marcellinus Comes, a sixth-century Eastern Roman historian and a courtier of Justinian I, mentions the Western Roman Empire in his Chronicle, which primarily covers the Eastern Roman Empire from 379 to 534. In the Chronicle, it is clear that Marcellinus made a clear divide between East and West, with mentions of a geographical east ("Oriens") and west ("Occidens") and an of imperial east ("Orientale imperium" and "Orientale respublica") and an imperial west ("Occidentalie imperium", "Occidentale regnum", "Occidentalis respublica", "Hesperium regnum", "Hesperium imperium" and "principatum Occidentis"). Furthermore, Marcellinus specifically designates some emperors and consuls as being "Eastern", "Orientalibus principibus" and "Orientalium consulum" respectively.[136] The term Hesperium Imperium, translating to "Western Empire", has sometimes been applied to the Western Roman Empire by modern historians as well.[137]

Though Marcellinus does not refer to the Empire as a whole after 395, only to its separate parts, he clearly identifies the term "Roman" as applying to the Empire as a whole. When using terms such as "us", "our generals", and "our emperor", Marcellinus distinguished both divisions of the Empire from outside foes such as the Sasanian Persians and the Huns.[136] This view is consistent with the view that contemporary Romans of the 4th and 5th centuries continued to consider the Empire as a single unit, although more often than not with two rulers instead of one.[80] The first time the Empire was divided geographically was during the reign of Diocletian, but there was precedent for multiple emperors. Before Diocletian and the Tetrarchy, there had been a number of periods where there was more than one co-emperor, such as with Caracalla and Geta in 210–211, who inherited the imperial throne from their father Septimius Severus, but Caracalla ruled alone after the murder of his brother.[138]

Attempted restorations of a Western court

The positions of Eastern and Western Augustus, established under Emperor Diocletian in 286 as the Tetrarchy, had been abolished by Emperor Zeno in 480 following the loss of direct control over the western territories. Declaring himself the sole Augustus, Zeno only exercised true control over the largely intact Eastern Empire and over Italy as the nominal overlord of Odoacer.[78] The reconquests under Justinian I would bring back large formerly Western Roman territories into Imperial control, and with them the Empire would begin to face the same problems it had faced under previous periods prior to the Tetrarchy when there had been only one ruler. Shortly after the reconquest of North Africa a usurper, Stotzas, appeared in the province (though he was quickly defeated).[139] As such, the idea of dividing the Empire into two courts out of administrative necessity would see a limited revival during the period that the Eastern Empire controlled large parts of the former West, both by courtiers in the East and enemies in the West.[140][141]

The earliest attempt at crowning a new Western Emperor after the abolition of the title occurred already during the Gothic Wars under Justinian. Belisarius, an accomplished general who had already successfully campaigned to restore Roman control over North Africa and large parts of Italy, including Rome itself, was offered the position of Western Roman Emperor by the Ostrogoths during his siege of Ravenna (the Ostrogothic, and previously Western Roman, capital) in 540. The Ostrogoths, desperate to avoid losing their control of Italy, offered the title and their fealty to Belisarius as Western Augustus. Justinian had expected to rule over a restored Roman Empire alone, with the Codex Justinianus explicitly designating the new Praetorian Prefect of Africa as the subject of Justinian in Constantinople.[142] Belisarius, loyal to Justinian, feigned acceptance of the title to enter the city, whereupon he immediately relinquished it. Despite Belisarius relinquishing the title, the offer had made Justinian suspicious and Belisarius was ordered to return east.[140]

At the end of Emperor Tiberius II's reign in 582, the Eastern Roman Empire retained control over relatively large parts of the regions reconquered under Justinian. Tiberius chose two Caesares, the general Maurice and the governor Germanus, and married his two daughters to them. Germanus had clear connections to the western provinces, and Maurice to the eastern provinces. It is possible that Tiberius was planning to divide the empire into western and eastern administrative units once more.[141] If so, the plan was never realized. At the death of Tiberius, Maurice inherited the entire empire as Germanus had refused the throne. Maurice established a new type of administrative unit, the Exarchate, and organized the remaining western territories under his control into the Exarchate of Ravenna and the Exarchate of Africa.[143]

Later claims to the Imperial title in the West

Denarius of Frankish king Charlemagne, who was crowned as Roman Emperor Karolus Imperator Augustus in the year 800 by Pope Leo III in opposition to the Roman Empire in the East, which was ruled by Irene, a woman. His coronation was strongly opposed by the Eastern Empire.

In addition to remaining as a concept for an administrative unit in the remaining Empire, the ideal of the Roman Empire as a mighty Christian Empire with a single ruler further continued to appeal to many powerful rulers in western Europe. With the papal coronation of Charlemagne as "Emperor of the Romans" in 800 AD, his realm was explicitly proclaimed as a restoration of the Roman Empire in Western Europe under the concept of translatio imperii. Though the Carolingian Empire collapsed in 888 and Berengar, the last "Emperor" claiming succession from Charlemagne, died in 924, the concept of a papacy- and Germanic-based Roman Empire in the West would resurface in the form of the Holy Roman Empire in 962. The Holy Roman Emperors would uphold the notion that they had inherited the supreme power and prestige of the Roman Emperors of old until the downfall of the Holy Roman Empire in 1806.[144]