Charles I of Anjou

| Charles I | |

|---|---|

His statue at the Royal Palace (Naples). | |

King of Sicily Contested by Peter I from 1282. | |

| Reign | 1266–1285 |

| Coronation | 5 January 1266 |

| Predecessor | Manfred |

| Successor | Peter I (island of Sicily) Charles II (mainland territories) |

Count of Anjou and Maine | |

| Reign | 1246–1285 |

| Successor | Charles II |

| Count of Provence | |

| Reign | 1246–1285 |

| Predecessor | Beatrice |

| Successor | Charles II |

| Count of Forcalquier | |

| Reign | 1246–1248 1256–1285 |

| Predecessor | Beatrice I Beatrice II |

| Successor | Beatrice II Charles II |

| Prince of Achaea | |

| Reign | 1278–1285 |

| Predecessor | William of Villehardouin |

| Successor | Charles II |

| Born | early 1226/1227 |

| Died | 7 January 1285 (Aged 57–59) Foggia, Kingdom of Naples |

| Burial | Naples Cathedral |

| Spouse | Beatrice of Provence (m. 1246, d. 1267) Margaret of Burgundy (m. 1268) |

| Issue More | Beatrice, Latin Empress Charles II, King of Naples Philip Elisabeth, Queen of Hungary |

| House | Anjou-Sicily |

| Father | Louis VIII, King of France |

| Mother | Blanche of Castile |

Charles I (early 1226/1227 – 7 January 1285), commonly called Charles of Anjou, was a member of the royal Capetian dynasty and the founder of the second House of Anjou. He was Count of Provence (1246–85) and Forcalquier (1246–48, 1256–85) in the Holy Roman Empire, Count of Anjou and Maine (1246–85) in France; he was also King of Sicily (1266–85) and Prince of Achaea (1278–85). In 1272, he was proclaimed King of Albania; and in 1277 he purchased a claim to the Kingdom of Jerusalem.

Being the youngest son of Louis VIII of France and Blanche of Castile, he was destined for a Church career until the early 1240s. He acquired Provence and Forcalquier through his marriage to their heiress, Beatrice. His attempts to secure comital rights brought him into conflict with his mother-in-law and the nobility. He received Anjou and Maine from his brother, Louis IX of France, in appanage. He accompanied Louis during the Seventh Crusade to Egypt. Shortly after he returned to Provence in 1250, Charles forced three wealthy free imperial cities—Marseilles, Arles and Avignon—to acknowledge his suzerainty.

Charles supported Margaret II, Countess of Flanders and Hainaut against her eldest son in exchange for Hainaut in 1253. Two years later Louis IX persuaded him to renounce the county, but compensated him by instructing Margaret to pay him 160,000 marks. Charles forced the rebellious Provençal nobles and towns into submission and expanded his suzerainty over a dozen towns and lordships in the Kingdom of Arles. In 1263, after years of negotiations, he accepted the offer of the Holy See to seize the Kingdom of Sicily from the Hohenstaufens. This kingdom included, in addition to the island of Sicily, southern Italy to well north of Naples and was known as the Regno. Pope Urban IV declared a crusade against the incumbent Manfred of Sicily and assisted Charles to raise funds for the military campaign.

Charles was crowned king in Rome on 5 January 1266. He annihilated Manfred's army and occupied the Regno almost without resistance. His victory over Manfred's young nephew, Conradin, at the Battle of Tagliacozzo in 1268 strengthened his rule. In 1270 he took part in the Eighth Crusade (which had been organized by Louis IX) and forced the Hafsid caliph of Tunis to pay a yearly tribute to him. Charles's victories secured his undisputed leadership among the popes' Italian partisans (known as Guelphs), but his influence on papal elections and his strong military presence in Italy disturbed the popes. They tried to channel his ambitions towards other territories and assisted him in acquiring claims to Achaea, Jerusalem and Arles through treaties. In 1281 Pope Martin IV authorised Charles to launch a crusade against the Byzantine Empire. Charles' ships were gathering at Messina, ready to begin the campaign when a riot—known as the Sicilian Vespers—broke out on 30 March 1282. It put an end to Charles' rule on the island of Sicily, but he was able to defend the mainland territories (or the Kingdom of Naples) with the support of France and the Holy See.

Contents

1 Early life

1.1 Childhood

1.2 Provence and Anjou

1.3 Seventh Crusade

2 Wider ambitions

2.1 Conflicts and consolidation

2.2 Conquest of the Regno

2.3 Conradin

3 Mediterranean empire

3.1 Italy

3.2 Eighth Crusade

3.3 Attempts to expand

3.4 Papal elections

3.5 End of the Church union

4 Collapse

4.1 Sicilian Vespers

4.2 War with Aragon

4.3 Death

5 Family

6 Legacy

7 Notes

8 References

9 Sources

10 Further reading

11 External links

Early life

Childhood

Charles was the youngest child of Louis VIII of France and Blanche of Castile.[1] The date of his birth was not recorded, but he was probably a posthumous son, born in early 1227.[note 1][2][3] Charles was Louis's only surviving son to be "born in the purple" (after his father's coronation), a fact he often emphasised in his youth, according to Matthew Paris.[2] He was the first Capet to be named for Charlemagne.[2]

Louis willed that his youngest sons were to be prepared for a career in the Roman Catholic Church.[2] The details of Charles' tuition are unknown, but he received a good education.[4][5] He understood the principal Catholic doctrines and could identify errors in Latin texts.[6] His passion for poetry, medical sciences and law is well documented.[4][5]

Charles would state during the canonisation of his brother, Louis IX of France, that their mother had a strong impact on her children's education.[1] Actually, Blanche was fully engaged in state administration, and could likely spare little time for her youngest children.[3][4] Charles lived at the court of a brother, Robert I, Count of Artois, from 1237.[4] About four years later he was put into the care of his youngest brother, Alphonse, Count of Poitiers.[4] His participation in his brothers' military campaign against Hugh X of Lusignan, Count of La Marche, in 1242 showed that he was no longer destined for a Church career.[4]

Provence and Anjou

Charles' coat-of-arms (Anjou ancient): France ancient with label Gules as charge

Raymond Berengar V of Provence died in August 1245,[7] bequeathing Provence and Forcalquier to his youngest daughter, Beatrice, allegedly because he had given generous dowries to her three sisters.[8][9] The dowries were actually not fully discharged,[5] causing two of her sisters, Margaret (Louis IX's wife) and Eleanor (the wife of Henry III of England), to believe that they had been unlawfully disinherited.[9] Their mother, Beatrice of Savoy, claimed that Raymond Berengar had willed the usufruct of Provence to her.[7][9]

Emperor Frederick II, Count Raymond VII of Toulouse and other neighbouring rulers proposed themselves or their sons as husbands for the young countess.[10] Her mother put her under the protection of the Holy See.[10] Louis IX and his wife suggested that Beatrice should be given in marriage to Charles.[9] To secure the support of France against Frederick II, Pope Innocent IV accepted their proposal.[9] Charles hurried to Aix-en-Provence at the head of an army to prevent other suitors from attacking.[9][11] He married Beatrice on 31 January 1246.[9][12] Provence was a part of the Kingdom of Arles and so of the Holy Roman Empire,[13] but Charles never swore fealty to the emperor.[14] He ordered a survey of the counts' rights and revenues, outraging both his subjects and his mother-in-law, who regarded this action as an attack against her rights.[13][15]

Being a younger child, destined for a Church career, Charles had not received an appanage (a hereditary county or duchy) from his father.[16] Louis VIII had willed that his fourth son, John, should receive Anjou and Maine upon reaching the age of majority, but John died in 1232.[17] Louis IX knighted Charles at Melun in May 1246 and three months later bestowed Anjou and Maine on him.[18][19] Charles rarely visited his two counties and appointed baillies (or regents) to administer them.[20]

While Charles was absent from Provence, Marseilles, Arles and Avignon—three wealthy cities, directly subject to the emperor—formed a league and appointed a Provençal nobleman, Barral of Baux, as the commander of their combined armies.[13] Charles' mother-in-law put the disobedient Provençals under her protection.[13] Charles could not deal with the rebels as he was about to join his brother's crusade.[13] To pacify his mother-in-law he acknowledged her right to rule Forcalquier and granted a third of his revenues from Provence to her.[13]

Seventh Crusade

The crusaders' defeat in the Battle of Al Mansurah in Egypt

In December 1244 Louis IX took a vow to lead a crusade.[21] Ignoring their mother's strong opposition his three brothers—Robert, Alphonse and Charles—also took the cross.[22] Preparations for the crusade lasted for years, with the crusaders embarking at Aigues-Mortes on 25 August 1248.[21][23] After spending several months in Cyprus they invaded Egypt on 5 June 1249.[24] They captured Damietta and decided to attack Cairo in November.[25] During their advance Jean de Joinville noted Charles' personal courage which saved dozens of crusaders' lives.[26] They were unable to reach Cairo because Egyptian troops surrounded them on 6 April 1250.[27] Charles was captured along with his brothers.[26] They were released in exchange of 800,000 bezants and the surrender of Damietta on 6 May.[27]

During their voyage to Acre,[27] Charles outraged Louis by gambling while the king was mourning the recent death of their brother, Robert of Artois.[26] Louis remained in the Holy Land, but Charles returned to France in October 1250.[13]

Wider ambitions

Conflicts and consolidation

During Charles' absence rebellions had broken out in Provence.[13] He applied both diplomacy and military force to deal with them.[13] The Archbishop of Arles and the Bishop of Digne ceded their secular rights in the two towns to Charles in 1250.[28] He received military assistance from his brother, Alphonse.[29] Arles was the first town to surrender to them in April 1251.[30] In May they forced Avignon to acknowledge their joint rule.[29][30] A month later Barral of Baux also capitulated.[30] Marseilles was the only town to resist for several months, but it also sought peace in July 1252.[30] Its burghers acknowledged Charles as their lord, but retained their self-governing bodies.[30]

Salt crystals in a puddle in Camargue: salt pans at the delta of the Rhone significantly increased Charles' revenues

Charles' officials continued to ascertain his rights,[31] visiting each town and holding public enquiries to obtain information about all claims.[31] The count's salt monopoly (or gabelle) was introduced in the whole county.[31] Income from the salt trade made up about 50% of comital revenues by the late 1250s.[31] Charles abolished local tolls and promoted shipbuilding and the cereal trade.[32] He ordered the issue of new coins, called provencaux, to enable the use of the local currency in smaller transactions.[33]

The Regno

Emperor Frederick II, who was also the ruler of Sicily, died in 1250. The Kingdom of Sicily, also known as the Regno, included the island of Sicily and southern Italy nearly as far as Rome. Pope Innocent IV claimed that the Regno had reverted to the Holy See.[34] The pope first offered the Regno to Richard of Cornwall, but Richard did not want to fight against Frederick's son, Conrad IV of Germany.[34] Then the pope proposed to enfeoff Charles with the kingdom.[34] Charles sought instructions from Louis IX who forbade him to accept the offer, because he regarded Conrad as the lawful ruler.[34] After Charles informed the Holy See on 30 October 1253 that he would not accept the Regno, the pope offered it to Edmund of Lancaster.[35]

Queen Blanche, who had administered France during Louis' crusade,[30] died on 1 December 1252.[36] Louis made Alphonse and Charles co-regents, so that he could remain in the Holy Land.[37]Margaret II, Countess of Flanders and Hainaut had come into conflict with her son by her first marriage, John of Avesnes.[38] After her sons by her second marriage were captured in July 1253, she needed foreign assistance to secure their release.[38] Ignoring Louis IX's 1246 ruling that Hainaut should pass to John, she promised the county to Charles.[38] He accepted the offer and invaded Hainaut, forcing most local noblemen to swear fealty to him.[30][38] After his return to France, Louis IX insisted that his ruling was to be respected.[30] In November 1255 he ordered Charles to restore Hainaut to Margaret, but her sons were obliged to swear fealty to Charles.[39] Louis also ruled that she was to pay 160,000 marks to Charles during the following 13 years.[39]

Charles returned to Provence, which had become restive again.[30] His mother-in-law continued to support the rebellious Boniface of Castellane and his allies, but Louis IX persuaded her to return Forcalquier to Charles and relinquish her claims for a lump sum payment from Charles and a pension from Louis in November 1256.[32][40] A coup by Charles' supporters in Marseilles resulted in the surrender of all political powers there to his officials.[41] Charles spent the next years expanding his power along the borders of Provence.[41] He received territories in the Lower Alps from the Dauphin of Vienne.[41]Raymond I of Baux, Count of Orange, ceded the title of regent of the Kingdom of Arles to him.[41] The burghers of Cuneo—a town strategically located on the routes to Lombardy—sought Charles' protection against Asti in July 1259.[42][43]Alba, Cherasco, Savigliano and other nearby towns acknowledged his rule.[44] The rulers of Mondovì, Ceva, Biandrate and Saluzzo did homage to him in 1260.[41]

Emperor Frederick II's illegitimate son, Manfred, had been crowned king of Sicily in 1258.[45] After the English barons had announced that they opposed a war against Manfred, Pope Alexander IV annulled the 1253 grant of Sicily to Edmund of Lancaster.[46] Alexander's successor, Pope Urban IV, was determined to put an end to the Emperor's rule in Italy.[47][48] He sent his notary, Albert of Parma, to Paris to negotiate with Louis IX for Charles to be placed on the Sicilian throne.[49] Charles met with the Pope's envoy in early 1262.[30]

Taking advantage of Charles' absence, Castellane stirred up a new revolt in Provence.[41][50] The burghers of Marseilles expelled Charles' officials, but Barral of Baux stopped the spread of the rebellion before Charles' return.[51] Charles renounced Ventimiglia in favour of Genoa to secure the neutrality of the republic.[52] He defeated the rebels and forced Castellane into exile.[52] The mediation of James I of Aragon brought about a settlement with Marseilles: its fortifications were dismantled and the townspeople surrendered their arms, but the town retained its autonomy.[52]

Conquest of the Regno

Charles' coronation

Louis IX decided to support Charles' military campaign in Italy in May 1263.[53] Pope Urban IV promised to proclaim a crusade against Manfred, while Charles pledged that he would not accept any offices in the Italian towns.[54] Manfred staged a coup in Rome, but the Guelphs elected Charles senator (or the head of the civil government of Rome).[54][55] He accepted the office, at which a group of cardinals requested that the Pope revoke the agreement with him, but the Pope, being otherwise defenceless against Manfred, could not break with Charles.[56]

In the spring of 1264 Cardinals Simon of Brie and Guy Foulquois were sent to France to reach a compromise and start raising support for the crusade.[49][56] Charles sent troops to Rome to protect the Pope against Manfred's allies.[57] At Foulquois' request, Charles' sister-in-law, Margaret (who had not abandoned her claims to her dowry) pledged that she would not take actions against Charles during his absence.[57] Foulquois also persuaded the French and Provençal prelates to offer financial support for the crusade.[55][57] Pope Urban died before the final agreement was concluded.[58] Charles made arrangements for his campaign against Sicily during the interregnum; he concluded agreements to secure his army's route across Lombardy and had the leaders of the Provençal rebels executed.[58]

Foulquois was elected pope in February 1265; he soon confirmed Charles' senatorship and urged him to come to Rome.[59] Charles agreed that he would hold the Kingdom of Sicily as the popes' vassal for an annual tribute of 8,000 ounces of gold.[55] He also promised that he would never seek the imperial title.[55] He embarked at Marseilles on 10 May and landed at Ostia ten days later.[58] He was installed as senator on 21 June and four cardinals invested him with the Regno a week later.[58] To finance further military actions he borrowed money from Italian bankers with the Pope's assistance, who had authorised him to pledge Church property.[60][61] Five cardinals crowned him king of Sicily on 5 January 1266.[61] The crusaders from France and Provence—reportedly 6,000 fully equipped mounted warriors, 600 mounted bowmen and 20,000 foot soldiers—arrived in Rome ten days later.[60][62]

Battle of Benevento

Charles decided to invade the Regno without delay, because he was unable to finance a lengthy campaign.[62][63] He left Rome on 20 January 1266.[63] He marched towards Naples, but changed his strategy after learning of a muster of Manfred's forces near Capua.[64] He led his troops across the Apennines towards Benevento.[64] Manfred also hurried to the town and reached it before Charles.[64] Worried that further delays might endanger his subjects' loyalty, Manfred attacked Charles' army, then in disarray from the crossing of the hills, on 26 February 1266.[64] In the ensuing battle, Manfred's army was defeated and he was killed.[64]

Resistance throughout the Regno collapsed.[62][65] All towns surrendered even before Charles' troops reached them.[65] The Saracens of Lucera—a Muslim colony established during Frederick II's reign[66]—paid homage to him.[65] His commander, Philip of Montfort, took control of the island of Sicily.[65] Manfred's widow, Helena of Epirus, and their children were captured.[67] Charles laid claim to her dowry—the island of Corfu and the region of Durazzo (now Durrës in Albania)—by right of conquest.[67] His troops seized Corfu before the end of the year.[68]

Conradin

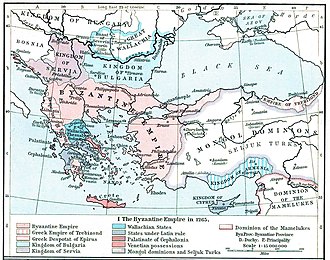

The Byzantine Empire and the Latin states in 1265

Charles was lenient with Manfred's supporters, but they did not believe that this conciliatory policy could last.[69] They knew that he had promised to return estates to the Guelph lords expelled from the Regno.[69] Neither could Charles gain the commoners' loyalty, partly because he continued enforcing the subventio generalis despite the popes declaring it an illegal charge.[70][71] He introduced a ban on the use of foreign currency in large transactions and made a profit of the compulsory exchange of foreign coinage for locally minted currency.[72] He also traded in grain, spices and sugar, through a joint venture with Pisan merchants.[73]

Pope Clement censured Charles for his methods of state administration, describing him as an arrogant and obstinate monarch.[74] The consolidation of Charles' power in northern Italy also alarmed Clement.[75] To appease the pope, Charles resigned his senatorship in May.[74][76] His successors, Conrad Monaldeschi and Luca Savelli, soon demanded the re-payment of the money that Charles and the Pope had borrowed from the Romans.[74]

Victories by the Ghibellines, the imperial family's supporters, forced the Pope to ask Charles to send his troops to Tuscany.[77] Charles' troops ousted the Ghibellines from Florence in April.[77] After being elected the Podestà (ruler) of Florence and Lucca for seven years, Charles hurried to Tuscany.[77] The Pope summoned him to Viterbo, forcing him to promise that he would abandon all claims to Tuscany in three years.[78]

The Pope wanted to change the direction of Charles' ambitions.[67] He persuaded Charles to conclude agreements with William of Villehardouin, Prince of Achaea, and the Latin Emperor Baldwin II in late May.[79] According to the first treaty, Villehardouin acknowledged Charles' suzerainty and made Charles' younger son, Philip, his heir, also stipulating that Charles would inherit Achaea if Philip died childless.[80][81] Baldwin confirmed the first agreement and renounced his claims to suzerainty over his vassals in favour of Charles.[81][82] Charles pledged that he would assist Baldwin in recapturing Constantinople from the Byzantine emperor, Michael VIII Palaiologos, in exchange for one third of the conquered lands.[83][84]

Charles returned to Tuscany and laid siege to the fortress of Poggibonsi, but it did not fall until the end of November.[85] Manfred's staunchest supporters had meanwhile fled to Bavaria to attempt to persuade Conrad IV's 15-year-old son Conradin to assert his hereditary right to the Regno.[86] After Conradin accepted their proposal, Manfred's former vicar in Sicily, Conrad Capece, returned to the island and stirred up a revolt.[86] At Capece's request Muhammad I al-Mustansir, the Hafsid caliph of Tunis,[87] allowed Manfred's former ally, Frederick of Castile, to invade Sicily from North Africa.[88] Frederick's brother, Henry—who had been elected senator of Rome—also offered support to Conradin.[86][89] Henry had been Charles' friend, but Charles had failed to repay a loan to him.[90]

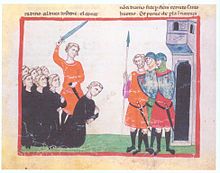

Execution of Conradin in 1268

Conradin left Bavaria in September 1267.[91] His supporters' revolt was spreading from Sicily to Calabria; the Saracens of Lucera also rose up.[91][92] Pope Clement urged Charles to return to the Regno, but he continued his campaign in Tuscany until March 1268[91] when he met with the Pope who made him the Imperial Vicar of Lombardy.[91] He marched to southern Italy and laid siege to Lucera, but he then had to hurry north to prevent Conradin's invasion of Abruzzo in late August.[93] At the Battle of Tagliacozzo, on 23 August 1268, it appeared that Conradin had won the day, but a sudden charge by Charles' reserve routed Conradin's army.[93]

The burghers of Potenza, Aversa and other towns in Basilicata and Apulia massacred their fellows who had agitated on Conradin's behalf, but the Sicilians and the Saracens of Lucera did not surrender.[62][94] Charles marched to Rome where he was again elected senator in September.[95] He appointed new officials to administer justice and collect state revenues.[95] New coins bearing his name were struck.[95] During the following decade, Rome was ruled by Charles' vicars, each appointed for one year.[95]

Conradin was captured at Torre Astura.[96] Most of his retainers were summarily executed, but Conradin and his friend, Frederick I, Margrave of Baden, were brought to trial for robbery and treason in Naples.[97] They were sentenced to death and beheaded on 29 October.[98]Conrad of Antioch was Conradin's only partisan to be released, but only after his wife threatened to execute the Guelph lords she held captive in her castle.[96] The Ghibellin noblemen of the Regno fled to the court of Peter III of Aragon, who had married Manfred's daughter, Constance.[99]

Mediterranean empire

Empire of Charles I of Anjou.

Italy

Charles as senator (statue by Arnolfo di Cambio in Rome)

Charles wife, Beatrice of Provence, had died in July 1267. The widowed Charles married Margaret of Nevers in November 1268.[100] She was co-heiress to her father, Odo, the eldest son of Hugh IV, Duke of Burgundy.[100] Pope Clement died on 29 November 1268.[95] The vacancy lasted for three years, which strengthened Charles' authority in Italy, but it also deprived him of the ecclesiastic support that only a pope could provide.[101][102]

Charles returned to Lucera to personally direct its siege in April 1269.[101] The Saracens and the Ghibellins who had escaped to the town[101] resisted until starvation forced them to surrender in August 1269.[62][103] Charles sent Philip and Guy of Montfort to Sicily to force the rebels there into submission, but they could only capture Augusta.[104] Charles made William l'Estandart the commander of the army in Sicily in August 1269.[104] L'Estandart captured Agrigento, forcing Frederick of Castile and Frederick Lancia to seek refuge in Tunis.[104] After L'Estandart's subsequent victory at Sciacca, only Capece resisted, but he also had to surrender in early 1270.[104]

Charles' troops forced Siena and Pisa—the last towns to resist him in Tuscany—to sue for peace in August 1270.[105] He granted privileges to the Tuscan merchants and bankers which strengthened their position in the Regno.[106][107] His influence was declining in Lombardy, because the Lombard towns no longer feared an invasion from Germany.[108] In May 1269 Charles sent Walter of La Roche to represent him in the province, but this failed to strengthen his authority.[108][109] In October Charles' officials convoked an assembly at Cremona, and invited the Lombard towns to attend.[108][109] The Lombard towns accepted the invitation, but some towns—Milan, Bologna, Alessandria and Tortona—only confirmed their alliance with Charles, without acknowledging his rule.[108][109]

Eighth Crusade

Louis IX never abandoned the idea of the liberation of Jerusalem, but he decided to begin his new crusade with a military campaign against Tunis.[110][111] According to his confessor, Geoffrey of Beaulieu, Louis was convinced that al-Mustansir of Tunis was ready to convert to Christianity.[110] The 13th-century historian Saba Malaspina stated that Charles persuaded Louis to attack Tunis, because he wanted to secure the payment of the tribute that the rulers of Tunis had paid to the former Sicilian monarchs.[112]

The French crusaders embarked at Aigues-Mortes on 2 July 1270; Charles departed from Naples six days later.[113] He spent more than a month in Sicily, waiting for his fleet.[113] By the time he landed at Tunis on 25 August,[113]dysentery and typhoid fever had decimated the French army.[111] Louis died on the day of Charles' arrival.[111]

The crusaders twice defeated Al-Mustansir's army, forcing him to sue for peace.[114] According to the peace treaty, signed on 1 November, Al-Mustansir agreed to fully compensate Louis' son and successor, Philip III of France, and Charles for the expenses of the military campaign and to release his Christian prisoners.[114] He also promised to pay a yearly tribute to Charles and to expel Charles' opponents from Tunis.[115] The gold from Tunis, along with silver from the newly opened mine at Longobucco, enabled Charles to mint new coins, known as carlini, in the Regno.[116]

Charles and Philip departed Tunis on 10 November.[111] A storm dispersed their fleet at Trapani and most of Charles' galleys were lost or damaged.[114] Genoese ships returning from the crusade were also sunk or forced to land in Sicily.[117] Charles seized the damaged ships and their cargo, ignoring all protests from the Ghibelline authorities of Genoa.[117] Before leaving Sicily he granted temporary tax concessions to the Sicilians, because he realised that the conquest of the island had caused much destruction.[118]

Attempts to expand

Charles accompanied Philip III as far as Viterbo in March 1271.[119] Here they failed to convince the cardinals to elect a new pope.[119] Charles' brother, Alphonse of Poitiers, fell ill.[120] Charles sent his best doctors to cure him, but Alphonse died.[120] He claimed the major part of Alphonse inheritance, including the Marquisate of Provence and the County of Poitiers, because he was Alphonse's nearest kin.[121] After Philip III objected, he took the case to the Parlement of Paris.[121] In 1284 the court ruled that appanages escheated to the French crown if their rulers died without descendants.[122]

Charles' Sicilian seal (from the Cabinet des Médailles in Paris)

An earthquake destroyed the walls of Durazzo in the late 1260s or early 1270s.[123][124] Charles' troops took possession of the town with the assistance of the leaders of the nearby Albanian communities.[125][126] Charles concluded an agreement with the Albanian chiefs, promising to protect them and their ancient liberties in February 1272.[125] He adopted the title of King of Albania and appointed Gazzo Chinardo as his vicar-general.[127][126] He also sent his fleet to Achaea to defend the principality against Byzantine attacks.[128]

Charles hurried to Rome to attend the enthronement of Pope Gregory X on 27 March 1272.[129] The new pope was determined to put an end to the conflicts between the Guelphs and the Ghibellines.[130] While in Rome Charles met with the Guelph leaders who had been exiled from Genoa.[117] After they offered him the office of captain of the people, Charles promised military assistance to them.[117] In November 1272 Charles commanded his officials to take prisoner all Genoese within his territories, except for the Guelphs, and to seize their property.[131][132] His fleet occupied Ajaccio in Corsica.[132] Pope Gregory condemned his aggressive policy, but proposed that the Genoese should elect Guelph officials.[132] Ignoring the pope's proposal, the Genoese made alliance with Alfonso X of Castille, William VII of Montferrat and the Ghibelline towns of Lombardy in October 1273.[132]

The conflict with Genoa prevented Charles from invading the Byzantine Empire, but he continued to forge alliances in the Balkan Peninsula.[133] The Bulgarian ruler, Konstantin Tih, was the first to conclude a treaty with him in 1272 or 1273.[127]John I Doukas of Thessaly and Stefan Uroš I, King of Serbia, joined the coalition in 1273.[127] However, Pope Gregory forbade Charles to attack, because he hoped to unify the Orthodox and Catholic churches with the assistance of Emperor Michael VIII.[134][135]

The renowned theologian Thomas Aquinas died unexpectedly near Naples on 7 March 1274, before departing to attend the Second Council of Lyon.[136] According to a popular legend, immortalised by Dante, Charles had him poisoned, because he feared that Aquinas would make complaint against him.[136] Historian Steven Runciman emphasises that "there is no evidence for supposing that the great doctor's death was not natural".[136] Southern Italian churchmen at the council accused Charles of tyrannical acts.[134] Their report reinforced the Pope's attempt to reach a compromise with Rudolf of Habsburg, who had been elected king by the prince-electors of the Holy Roman Empire.[137] In June, the Pope acknowledged Rudolf as the lawful ruler of both Germany and Italy.[137] Charles' sisters-in-law, Margaret and Eleanor, approached Rudolf, claiming that they had been unlawfully disinherited in favour of Charles' late wife.[138][139]

Michael VIII's personal envoy announced at the Council of Lyon on 6 July that he had accepted the Catholic creed and papal primacy.[84] About three weeks later, Pope Gregory again prohibited Charles from launching military actions against the Byzantine Empire.[140] The Pope also tried to mediate a truce between Charles and Michael, but the latter choose to attack the smaller states of the Balkans, including Charles' vassals.[134] The Byzantine fleet took control of the maritime routes between Albania and southern Italy in the late 1270s.[141] Gregory only allowed Charles to send reinforcements to Achaea.[134] The organisation of a new crusade to the Holy Land remained the Pope's principal object.[142] He persuaded Charles to start negotiations with Maria of Antioch about purchasing her claim to the Kingdom of Jerusalem.[143] The High Court of Jerusalem had already rejected her in favour of Hugh III of Cyprus,[143] but the Pope had a low opinion of Hugh.[144]

The war with Genoa and the Lombard towns increasingly occupied Charles' attention.[145] He appointed his nephew, Robert II of Artois, as his deputy in Piedmont in October 1274, but Artois could not prevent Vercelli and Alessandria from joining the Ghibelline League.[145] The following summer, a Genoese fleet plundered Trapani and the island of Gozo.[145] Convinced that only Rudolf I could achieve a compromise between the Guelphs and Ghibellines, the Pope urged the Lombard towns to send envoys to him.[145] He also urged Charles to renounce Tuscany.[137] In the autumn of 1275 the Ghibellines offered to make peace with Charles, but he did not accept their terms.[145] Early the next year the Ghibellines defeated his troops at Col de Tende, forcing them to withdraw to Provence.[145]

Papal elections

The popes' palace in Viterbo

Pope Gregory X died on 10 January 1276.[146] After the hostility he experienced during Gregory's pontificate, Charles was determined to secure the election of a pope willing to support his plans.[147] Gregory's successor, Pope Innocent V, had always been Charles' partisan and he rapidly confirmed Charles' ranks of senator of Rome and imperial vicar of Tuscany.[148] He also mediated a peace treaty between Charles and Genoa,[134] which was signed in Rome on 22 June 1276.[149] Charles restored the privileges of the Genoese merchants and renounced his conquests, and the Genoese acknowledged his rule in Ventimiglia.[149]

Pope Innocent died on 30 June 1276.[149] After the cardinals assembled in the Lateran Palace, Charles' troops surrounded it, enabling only his allies to communicate with other cardinals and with outsiders.[149] On 11 July the cardinals elected Charles' old friend, Ottobuono de' Fieschi, pope, but he died on 18 August.[150] The cardinals met again, this time at Viterbo.[151] Although Charles was staying in the nearby Vetralla, he could not directly influence the election.[151]Pope John XXI, who was elected on 20 September, excommunicated Charles' opponents in Piedmont and prohibited Rudolf from coming to Lombardy, but did not forbid the Lombardian Guelph leaders swearing fealty to Rudolf.[151] The Pope also confirmed the treaty concluded by Charles and Maria of Antioch on 18 March which transferred her claims to Jerusalem to Charles for 1,000 bezants and a pension of 4,000 livres tournois.[151][152]

Charles' coat-of-arms from 1277: Anjou ancient party per pale with the arms of the Kingdom of Jerusalem

Charles appointed Roger of San Severino to administer the Kingdom of Jerusalem as his bailiff.[152] San Severino landed at Acre on 7 June 1277.[153] Hugh III's bailliff, Balian of Arsuf, surrendered the town without resistance.[154] Although only the Knights Hospitaller and the Venetians acknowledged Charles as the lawful ruler, the barons of the realm also paid homage to San Severino in January 1278, after he had threatened to confiscate their estates.[152][154] The Mamluks of Egypt had already confined the kingdom to a coastal strip covering 2,600 km2 (1,000 square miles)[154] and Charles had ordered San Severino to avoid conflicts with Egypt.[155]

Pope John died on 20 May 1277.[156] Charles was ill and could not prevent the election of the head of the anti-French cardinals, Giovanni Gaetano Orsini (Pope Nicholas III), on 25 November.[157] The Pope soon declared that no foreign prince could rule in Rome[158] and reminded Charles that he had been elected senator for ten years.[159] Charles swore fealty to the new pope on 24 May 1278 after lengthy negotiations.[159] He had to pledge that he would renounce both the senatorship of Rome and the vicariate of Tuscany in four months.[159] On the other hand, Nicholas III confirmed the excommunication of Charles' enemies in Piedmont and started negotiations with Rudolf to prevent him from making an alliance against Charles with Margaret of Provence and her nephew, Edward I of England.[160]

Charles announced his resignation from the senatorship and the vicariate on 30 August 1278.[161] He was succeeded by the Pope's brother, Matteo Orsini, in Rome, and by the Pope's nephew, Cardinal Latino Malabranca, in Tuscany.[161] To ensure that Charles fully abandoned his ambitions in central Italy the Pope started negotiations with Rudolf about the restoration of the Kingdom of Arles for Charles' grandson, Charles Martel.[158] Margaret of Provence sharply opposed the plan, but Philip III of France did not stand by his mother.[161] After lengthy negotiations, in the summer of 1279 Rudolf recognised Charles as the lawful ruler of Provence without demanding his oath of fealty.[161] An agreement about Charles Martel's rule in Arles and his marriage to Rudolf's daughter, Clemence, was signed in May 1280.[161] The plan disturbed the rulers of the lands along the Upper Rhone, especially Duke Robert II and Count Otto IV of Burgundy.[162]

Charles had meanwhile inherited the Principality of Achaea from William II of Villehardouin, who had died on 1 May 1278.[152][163] He appointed the unpopular senechal of Sicily, Galeran of Ivry, as his baillif in Achaea.[164][165] Galeran could not pay his troops who started to pillage the peasants' homes.[165]John I de la Roche, Duke of Athens, had to lend money to him to finance their salaries.[164]Nicephoros I of Epirus acknowledged Charles' suzerainty on 14 March 1279 to secure his assistance against the Byzantines.[163] Nicephoros also ceded three towns—Butrinto, Sopotos and Panormos—to Charles.[163]

Pope Nicholas died on 22 August 1280.[166] Charles sent agents to Viterbo to promote the election of one of his supporters, taking advantage of the rift between the late pope's relatives and other Italian cardinals.[166] When a riot broke out in Viterbo, after the cardinals had not reached a decision for months, Charles' troops took control of the town.[166] On 22 February 1281 his staunchest supporter, Simon of Brie, was elected pope.[167] Pope Martin IV dismissed his predecessor's relatives and made Charles the senator of Rome again.[168][169]Guido I da Montefeltro rose up against the pope, but Charles' troops under Jean d'Eppe stopped the spread of the rebellion at Forlì.[168] Charles also sent an army to Piedmont, but Thomas I, Marquess of Saluzzo, annihilated it at Borgo San Dalmazzo in May.[170]

End of the Church union

Pope Martin excommunicated Emperor Michael VIII on 10 April 1281 because the emperor had not imposed the Church union in his empire.[152][171] The Pope soon authorised Charles to invade the empire.[171] Charles' vicar in Albania, Hugh of Sully, had already laid siege to the Byzantine fortress of Berat.[164] A Byzantine army of relief under Michael Tarchaneiotes and John Synadenos arrived in March 1281.[172] Sully was ambushed and captured, his army put to flight and the interior of Albania was lost to the Byzantines.[173] On 3 July 1281 Charles and his son-in-law, Philip of Courtenay, the titular Latin emperor, made an alliance with Venice "for the restoration of the Roman Empire".[174] They decided to start a full-scale campaign early the next year.[171]

Margaret of Provence called Robert and Otto of Burgundy and other lords who held fiefs in the Kingdom of Arles to a meeting at Troyes in the autumn of 1281.[175] They were willing to unite their troops to prevent Charles' army from taking possession of the kingdom, but Philip III of France strongly opposed his mother's plan and Edward I of England would not promise any assistance to them.[175] Charles acknowledged that his wife held the County of Tonnerre and her other inherited estates as a Burgundian fief, which appeased Robert of Burgundy.[176] Charles' ships started to assemble at Marseilles to sail up the Rhone in the spring of 1282.[175] Another fleet was gathering at Messina to start the crusade against the Byzantine Empire.[177]

Collapse

Sicilian Vespers

Always in need of funds, Charles could not cancel the subventio generalis, although it was the most unpopular tax in the Regno.[178] Instead he granted exemptions to individuals and communities, especially to the French and Provençal colonists, which increased the burden on those who did not enjoy such privileges.[179] The yearly, or occasionally more frequent, obligatory exchange of the deniers—the coins almost exclusively used in local transactions—was also an important, and unpopular, source of revenue for the royal tresaury.[180][181] Charles took out enforced loans whenever he needed "immediately a large sum of money for certain arduous and pressing business", as he explained in one of his decrees.[182]

Purveyances, the requisitioning of goods, increased the unpopularity of Charles' government in the Regno.[182] His subjects were forced to guard prisoners or lodge soldiers in their homes.[182] The restoration of old fortresses, bridges and aqueducts and the building of new castles required the employment of craftsmen, although most of them were unwilling to participate in such lengthy projects.[183] Thousands of people were forced to serve in the army in foreign lands, especially after 1279.[182][184] Trading in salt was declared a royal monopoly.[185] In December 1281, Charles again ordered the collection of the subventio generalis, requiring the payment of 150% of the customary amount.[178]

The Church of the Holy Spirit in Palermo (or the "Church of the Vespers")

Charles did not pay attention to the island of Sicily, although it had been the centre of resistance against him in 1268.[186] He transferred the capital from Palermo to Naples.[19] He did not visit the island after 1271, preventing Sicilians from directly informing him of their grievances.[186][187] Sicilian noblemen were seldom employed as royal officials, although he often appointed their southern Italian peers to represent him in his other realms.[186] Furthermore, having seized large estates on the island in the late 1260s Charles almost exclusively employed French and Provençal clerics to administer the royal demesne.[118]

Popular stories credited John of Procida—Manfred of Sicily's former chancellor—with staging an international plot against Charles.[188][189] Legend says that he visited Constantinople, Sicily and Viterbo in disguise in 1279 and 1280 to convince Michael VIII, the Sicilian barons and Pope Nicholas III to support a revolt.[190] On the other hand, Michael VIII would later claim that he "was God's instrument in bringing freedom to the Sicilians" in his memoirs.[191] The emperor's wealth enabled him to send money to the discontented Sicilian barons.[192] Peter III of Aragon decided to lay claim to the Regno in late 1280: he did not hide his disdain when he met with Charles' son, Charles, Duke of Salerno, in Toulouse in December 1280.[190] He began to assemble a fleet, ostensibly for another crusade to Tunis.[193]

Rioting broke out in Sicily after a burgher of Palermo killed a drunken French soldier who had insulted his wife before the Church of the Holy Spirit on Easter Monday (30 March)[194] of 1282.[195][196] When the soldier's comrades attacked the murderer, the mob turned against them and started to massacre all the French in the town.[195] The riot, known since the 16th century as the Sicilian Vespers,[197] developed into an uprising and most of Charles' officials were killed or forced to flee the island.[195] Charles ordered the transfer of soldiers and ships from Achaea to Sicily, but could not stop the spread of the revolt to Calabria.[198] San Severino also had to return to Italy, accompanied by the major part of the garrison at Acre.[199]Odo Poilechien, who succeeded him in Acre, had limited authority.[199]

The burghers of the major Sicilian towns established communes which sent delegates to Pope Martin, asking him to take them under the protection of the Holy See.[200][201] Instead of accepting their offer, the pope excommunicated the rebels on 7 May.[202] Charles issued an edict on 10 June, accusing his officials of having ignored his instructions on good administration, but he failed to promise fundamental changes.[198] In July he sailed to Sicily and laid siege to Messina.[198]

War with Aragon

Peter III of Aragon's envoy, William of Castelnou, started negotiations with the rebels' leaders in Palermo.[203] Realizing that they could not resist without foreign support, they acknowledged Peter and Constance as their king and queen.[203] They appointed envoys to accompany Castelnou to Collo where the Aragonese fleet was assembling.[204] After a short hesitation, Peter decided to intervene on the rebels' behalf and sailed to Sicily.[205] He was declared king of Sicily at Palermo on 4 September.[198] Thereafter two realms, each ruled by a monarch styled king (or queen) of Sicily coexisted for more than a century, with Charles and his successors ruling in southern Italy (known as the Kingdom of Naples), and with Peter and his descendants on the island of Sicily.[206][207]

In the face of the Aragonese landing, Charles was compelled to withdraw from the island, but the Aragonese moved swiftly and destroyed part of his army and most of his baggage.[208][209] Peter took control of the whole island and sent troops to Calabria, but they could not prevent Charles of Salerno from leading an army of 600 French knights to join his father at Reggio Calabria.[210] Further French troops arrived under the command of Charles' nephews, Robert II of Artois and Peter of Alençon, in November.[210] In the same month, the pope excommunicated Peter.[211]

Neither Peter nor Charles could afford to wage a lengthy war.[211][212] Charles made an astonishing proposal in late December 1282, challenging Peter for a judicial duel.[213] Peter insisted that the war should be continued, but agreed that a battle between the two kings, each accompanied by 100 knights, should decide the possession of Sicily.[213] They agreed that the duel should take place at Bordeaux on 1 June 1283, but they did not fix the hour.[213][214] Charles appointed Charles of Salerno to administer the Regno during his absence.[213] To secure the loyalty of the local lords in Achaea, he made one of their peers, Guy of Dramelay, baillif.[197] Pope Martin declared the war against the Sicilians a crusade on 13 January 1283.[215] Charles met with the Pope in Viterbo on 9 March, but he ignored the Pope's ban on his duel with Peter of Aragon.[213] After visiting Provence and Paris in April, he left for Bordeaux to meet with Peter.[216] The duel turned into a farce; the two kings each arriving at different times on the same day, declaring a victory over their absent opponent, and departing.[217]

Skirmishes and raids continued to occur in southern Italy.[218] Aragonese guerillas attacked Catona and killed Peter of Alençon in January 1283; the Aragonese seized Reggio Calabria in February; and the Sicilian admiral, Roger of Lauria, annihilated a newly raised Provençal fleet at Malta in April.[219] However, tensions arose between the Aragonese and the Sicilians and in May 1283 one of the leaders of the anti-Angevin rebellion, Walter of Caltagirone, was executed for his secret correspondence with Charles' agents.[220] Pope Martin declared the war against Aragon a crusade and conferred the kingdom upon Philip III of France's son, Charles of Valois, on 2 February 1284.[221]

Charles started to raise new troops and a fleet in Provence, and instructed his son, Charles of Salerno, to maintain a defensive posture until his return.[222] Roger of Lauria based a small squadron on the island of Nisida to blockade Naples in May 1284.[223] Charles of Salerno attempted to destroy the squadron, but most of his fleet was captured, and he himself was taken prisoner after a short, sharp fight on 5 June.[223] News of the reverse caused a riot in Naples, but the papal legate, Gerard of Parma, crushed it with the assistance of local noblemen.[224] Charles learnt of the disaster when he landed at Gaeta on 6 June.[224] He was furious at Charles of Salerno and his disobedience.[224] He allegedly stated that "Who loses a fool loses nothing", referring to his son's capture.[224]

Charles left Naples for Calabria on 24 June 1284.[225] A huge army—reportedly 10,000 mounted warriors and 40,000 foot-soldiers—accompanied him as far as Reggio Calabria.[225] He laid siege to the town by sea and land in late July.[226] He tried to land in Sicily, but his forces were forced to withdraw.[226] After Lauria landed troops near Reggio Calabria, Charles had to lift the siege and retreat from Calabria on 3 August.[226]

Death

Charles' death

Charles went to Brindisi and made preparations for a campaign against Sicily in the new year.[227] He dispatched orders to his officials for the collection of the subventio generalis.[199] However, he fell seriously ill before moving to Foggia on 30 December.[199] He made his last will on 6 January 1285, appointing Robert II of Artois regent for his grandson, Charles Martel, who was to rule his realms until Charles of Salerno was released.[228][229] He died in the morning of 7 January.[230] He was buried in a marble sepulchre in Naples, but his heart was placed at the Couvent Saint-Jacques in Paris.[231][230] His corpse was moved to a chapel of the newly built Naples Cathedral in 1296.[229]

Family

.mw-parser-output table.ahnentafel{border-collapse:separate;border-spacing:0;line-height:130%}.mw-parser-output .ahnentafel tr{text-align:center}.mw-parser-output .ahnentafel-t{border-top:#000 solid 1px;border-left:#000 solid 1px}.mw-parser-output .ahnentafel-b{border-bottom:#000 solid 1px;border-left:#000 solid 1px}

| Ancestors of Charles I of Naples[232][233][234] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Charles and his first wife

All records show that Charles was a faithful husband and a caring father.[235] His first wife, Beatrice of Provence, gave birth to at least six children.[100] According to contemporaneous gossips, she persuaded Charles to claim the Regno, because she wanted to wear a crown like his sisters.[236] Before she died in July 1267,[85] she had willed the usufruct of Provence to Charles.[29]

- Blanche, the eldest daughter of Charles and Beatrice, became the wife of Robert of Béthune in 1265, but she died four years later.[237]

Beatrice, her younger sister, married Philip, the titular Latin Emperor, in 1273.[238]

Elisabeth, Charles' youngest daughter, was given in marriage to the future Ladislaus IV of Hungary in 1269, but Ladislaus preferred his mistresses to her.[184][239]

- Charles II, Charles' eldest son and namesake was granted the Principality of Salerno in 1272.[240]Charles the Lame (as he was called) and his wife, Maria of Hungary, had fourteen children, which secured the survival of the Capetian House of Anjou.[225]

Philip, Charles and Beatrice's next son, was elected king of Sardinia by the local Guelphs in 1269, but without the pope's consent.[201] He died childless in 1278.[240]

- Robert, Charles' third son, died in 1265.[240]

The widowed Charles first proposed himself to Margaret of Hungary.[241] However, Margaret, who had been brought up in a Dominican nunnery, did not want to marry.[242] According to legends, she disfigured herself to prevent the marriage.[241] Charles and his second wife, Margaret of Nevers, had children who did not survive to adulthood.[243]

Legacy

The works of Bartholomaeus of Neocastro and Saba Malaspina strongly influenced modern views about Charles, although they were biased.[207][244] The former described Charles as a tyrant to justify the Sicilian Vespers, the latter argued for the cancellation of the crusade against Aragon in 1285.[244] Charles had continued his imperial predecessors' policies in several fields, including coinage, taxation, and the employment of unpopular officials from Amalfi.[245] Nevertheless, the monarchy underwent a "Frenchification" or "Provençalistion" during his reign.[246] He donated estates in the Regno to about 700 noblemen from France or Provence.[247] He did not adopt the rich ceremonial robes, inspired by Byzantine and Islamic art, of earlier Sicilian kings, but dressed like other western European monarchs,[246] or as "a simple knight", as it was observed by Thomas Tuscus in 1267.[248]

Charles as count of Provence (statue by Louis-Joseph Daumas in Hyères)

Around 1310, Giovanni Villani stated that Charles had been the most powerful Christian monarch in the late 1270s.[249]Luchetto Gattilusio compared Charles directly with Charlemagne.[249] Both reports demonstrate that Charles was regarded almost as an emperor.[249] Among modern historians, Runciman says that Charles tried to build an empire in the eastern Mediterraneum;[230]Gérard Sivéry writes that he wanted to dominate the west; and Jean Dunbabin argues that his "agglomeration of lands was in the process of forming an empire".[250]

Historian Hiroshi Takayama concludes that Charles' dominion "was too large to control".[251] Nevertheless, economic links among his realms strengthened during his reign.[252] Provençal salt was transported to his other lands, grain from the Regno was sold in Achaea, Albania, Acre and Tuscany, and Tuscan merchants settled in Anjou, Maine, Sicily and Naples.[253] His highest-ranking officials were transferred from their homelands to represent him in other territories: his senechals in Provence were from Anjou; French and Provençal noblemen held the highest offices in the Regno; and he chose his vicars in Rome from among southern Italian and Provençal nobles.[254] Although his empire collapsed before his death, his son retained southern Italy and Provence.[255]

Charles always emphasised his royal rank, but did not adopt "imperial rhetoric".[256] His renowned justiciar, Marino de Caramanico, developed a new political theory, which denied the emperors' monopoly on law-making and emphasised Charles' full competence to issue decrees.[257] To promote legal education Charles paid high salaries—20–50 ounces of gold in a year—to masters of law at the University of Naples.[258] Masters of medicine received similar remunerations, and the university became a principal centre of medical science.[259] Charles' personal interest in medicine grew during his life and he borrowed Arabic medical texts from the rulers of Tunis to have them translated.[260] He employed at least one Jewish scholar, Moses of Palermo, who could translate texts from Arabic to Latin.[261]Muhammad ibn Zakariya al-Razi's medical encyclopaedia, known as Kitab al-Hawi, was one of the books translated at his order.[260]

Charles was also a poet, which distinguished him from his Capetian relatives.[262] He composed lovesongs and a partimen (the latter with Pierre d'Angicourt).[262] He was requested to judge at two poetic competitions in his youth, but modern scholars do not esteem his poetry.[263]

The Provençal troubadours were mostly critical when writing of Charles, but French poets were willing to praise him.[264]Bertran d'Alamanon wrote a poem against the salt tax and Raimon de Tors de Marseilha rebuked Charles for invading the Regno. Adam de la Halle dedicated an unfinished epic poem to Charles and Jean de Meun glorified his victories.[265] Dante described Charles—"who bears a manly nose"—singing peacefully together with his one-time rival, Peter III of Aragon, in Purgatory.[266]

Charles also showed interest in architecture.[267] He designed a tower in Brindisi, but it soon collapsed.[268] He ordered the erection of the Castel Nuovo in Naples, of which only the palatine chapel survives.[268] He is also credited with the introduction of French-style glassed windows in southern Italy.[269]

Notes

^ Historian Peter Herde notes that Charles may have also been identical with the first son of Louis VIII and Blanche born in 1226, Stephen, or with the unnamed son who was born in late 1226. If Charles was identical with Stephen, he must have changed his name before the late 1230s. (Dunbabin (1998), p. 10.)

References

^ ab Dunbabin 1998, pp. 10–11.

^ abcd Dunbabin 1998, p. 10.

^ ab Runciman 1958, p. 71.

^ abcdef Dunbabin 1998, p. 11.

^ abc Runciman 1958, p. 72.

^ Dunbabin 1998, pp. 11–12.

^ ab Cox 1974, pp. 145–146.

^ Cox 1974, pp. 146, 151.

^ abcdefg Dunbabin 1998, p. 42.

^ ab Cox 1974, p. 147.

^ Cox 1974, p. 152.

^ Cox 1974, p. 153.

^ abcdefghi Runciman 1958, p. 73.

^ Dunbabin 1998, p. 44.

^ Cox 1974, p. 160.

^ Dunbabin 1998, p. 12.

^ Dunbabin 1998, pp. 12–13.

^ Dunbabin 1998, p. 13.

^ ab Takayama 2004, p. 78.

^ Dunbabin 1998, p. 30.

^ ab Asbridge 2012, p. 580.

^ Asbridge 2012, pp. 580–581.

^ Lock 2006, p. 10.

^ Lock 2006, pp. 177–178.

^ Lock 2006, p. 178.

^ abc Dunbabin 1998, p. 194.

^ abc Lock 2006, p. 108.

^ Dunbabin 1998, p. 50.

^ abc Dunbabin 1998, p. 43.

^ abcdefghij Runciman 1958, p. 74.

^ abcd Dunbabin 1998, p. 48.

^ ab Dunbabin 1998, p. 47.

^ Dunbabin 1998, p. 46.

^ abcd Runciman 1958, p. 57.

^ Runciman 1958, p. 58.

^ Lock 2006, p. 109.

^ Dunbabin 1998, p. 16.

^ abcd Dunbabin 1998, p. 37.

^ ab Dunbabin 1998, p. 38.

^ Runciman 1958, pp. 74–75.

^ abcdef Runciman 1958, p. 75.

^ Dunbabin 1998, p. 79.

^ Cox 1974, p. 285.

^ Cox 1974, p. 286.

^ Lock 2006, p. 111.

^ Runciman 1958, p. 63.

^ Housley 1982, p. 17.

^ Takayama 2004, p. 76.

^ ab Housley 1982, p. 18.

^ Dunbabin 1998, pp. 77–78.

^ Runciman 1958, pp. 75–76.

^ abc Runciman 1958, p. 76.

^ Dunbabin 1998, p. 131.

^ ab Runciman 1958, p. 78.

^ abcd Dunbabin 1998, p. 132.

^ ab Runciman 1958, p. 79.

^ abc Runciman 1958, p. 81.

^ abcd Runciman 1958, p. 82.

^ Runciman 1958, pp. 82–83.

^ ab Runciman 1958, p. 87.

^ ab Dunbabin 1998, p. 133.

^ abcde Housley 1982, p. 19.

^ ab Runciman 1958, p. 90.

^ abcde Runciman 1958, p. 91.

^ abcd Runciman 1958, p. 96.

^ Housley 1982, p. 16.

^ abc Dunbabin 1998, p. 89.

^ Runciman 1958, p. 136.

^ ab Dunbabin 1998, p. 56.

^ Dunbabin 1998, p. 57.

^ Takayama 2004, p. 77.

^ Dunbabin 1998, pp. 163–164.

^ Dunbabin 1998, p. 158.

^ abc Runciman 1958, p. 98.

^ Runciman 1958, pp. 98–99.

^ Dunbabin 1998, p. 134.

^ abc Runciman 1958, p. 100.

^ Runciman 1958, pp. 100–101.

^ Dunbabin 1998, pp. 89, 134.

^ Fine 1994, p. 168.

^ ab Lock 2006, p. 114.

^ Fine 1994, p. 170.

^ Dunbabin 1998, pp. 94, 137.

^ ab Harris 2014, p. 202.

^ ab Runciman 1958, p. 101.

^ abc Runciman 1958, p. 103.

^ Abulafia 2000, p. 105.

^ Runciman 1958, pp. 99, 103.

^ Dunbabin 1998, p. 87.

^ Runciman 1958, p. 99.

^ abcd Runciman 1958, p. 105.

^ Metcalfe 2009, p. 292.

^ ab Runciman 1958, p. 109.

^ Runciman 1958, pp. 118, 124.

^ abcde Runciman 1958, p. 118.

^ ab Runciman 1958, p. 114.

^ Runciman 1958, pp. 114–115.

^ Runciman 1958, p. 115.

^ Dunbabin 1998, p. 99.

^ abc Dunbabin 1998, p. 182.

^ abc Runciman 1958, p. 119.

^ Dunbabin 1998, p. 136.

^ Metcalfe 2009, p. 293.

^ abcd Runciman 1958, p. 124.

^ Runciman 1958, p. 120.

^ Dunbabin 1998, p. 84.

^ Runciman 1958, pp. 120–121.

^ abcd Dunbabin 1998, p. 80.

^ abc Runciman 1958, p. 122.

^ ab Dunbabin 1998, p. 196.

^ abcd Lock 2006, p. 183.

^ Dunbabin 1998, p. 195.

^ abc Runciman 1958, p. 142.

^ abc Runciman 1958, p. 143.

^ Runciman 1958, pp. 143–144.

^ Dunbabin 1998, pp. 157, 161.

^ abcd Runciman 1958, p. 150.

^ ab Dunbabin 1998, p. 106.

^ ab Runciman 1958, p. 145.

^ ab Dunbabin 1998, p. 17.

^ ab Dunbabin 1998, p. 39.

^ Dunbabin 1998, pp. 39–40.

^ Nicol 1984, pp. 14–15.

^ Fine 1994, p. 184.

^ ab Nicol 1984, p. 15.

^ ab Dunbabin 1998, p. 90.

^ abc Fine 1994, p. 185.

^ Dunbabin 1998, p. 91.

^ Runciman 1958, p. 146.

^ Runciman 1958, pp. 150–151.

^ Dunbabin 1998, p. 82.

^ abcd Runciman 1958, p. 156.

^ Runciman 1958, pp. 156, 158.

^ abcde Dunbabin 1998, p. 137.

^ Fine 1994, p. 186.

^ abc Runciman 1958, p. 161.

^ abc Dunbabin 1998, p. 138.

^ Runciman 1958, p. 167.

^ Bárány 2010, p. 62.

^ Runciman 1958, p. 166.

^ Nicol 1984, p. 18.

^ Runciman 1958, pp. 168–169.

^ ab Lock 2006, p. 118.

^ Runciman 1958, p. 169.

^ abcdef Runciman 1958, p. 168.

^ Runciman 1958, p. 170.

^ Dunbabin 1998, pp. 138–139.

^ Runciman 1958, pp. 171–172.

^ abcd Runciman 1958, p. 172.

^ Runciman 1958, pp. 172–173.

^ abcd Runciman 1958, p. 173.

^ abcde Lock 2006, p. 119.

^ Runciman 1958, p. 178.

^ abc Runciman 1958, p. 179.

^ Dunbabin 1998, p. 97.

^ Runciman 1958, pp. 181–182.

^ Runciman 1958, p. 182.

^ ab Dunbabin 1998, p. 139.

^ abc Runciman 1958, p. 183.

^ Runciman 1958, pp. 183–184.

^ abcde Runciman 1958, p. 185.

^ Runciman 1958, pp. 192–193.

^ abc Nicol 1984, p. 23.

^ abc Lock 1995, p. 93.

^ ab Runciman 1958, p. 196.

^ abc Runciman 1958, p. 190.

^ Runciman 1958, pp. 190–191.

^ ab Runciman 1958, p. 191.

^ Dunbabin 1998, p. 141.

^ Runciman 1958, p. 192.

^ abc Fine 1994, p. 193.

^ Nicol 1984, p. 26.

^ Nicol 1984, p. 27.

^ Runciman 1958, p. 194.

^ abc Runciman 1958, p. 193.

^ Dunbabin 1998, p. 36.

^ Runciman 1958, p. 212.

^ ab Dunbabin 1998, p. 102.

^ Dunbabin 1998, p. 103.

^ Abulafia 2000, p. 103.

^ Dunbabin 1998, pp. 103–104.

^ abcd Dunbabin 1998, p. 104.

^ Dunbabin 1998, p. 161.

^ ab Abulafia 2000, p. 109.

^ Dunbabin 1998, p. 157.

^ abc Dunbabin 1998, p. 105.

^ Abulafia 2000, p. 108.

^ Dunbabin 1998, p. 101.

^ Abulafia 2000, p. 106.

^ ab Runciman 1958, p. 206.

^ Harris 2014, p. 203.

^ Runciman 1958, p. 207.

^ Runciman 1958, p. 210.

^ Lock 2006, p. 120.

^ abc Dunbabin 1998, p. 107.

^ Runciman 1958, pp. 214–215.

^ ab Lock 1995, p. 94.

^ abcd Dunbabin 1998, p. 109.

^ abcd Runciman 1958, p. 254.

^ Runciman 1958, p. 220.

^ ab Abulafia 2000, p. 107.

^ Runciman 1958, p. 221.

^ ab Runciman 1958, p. 226.

^ Runciman 1958, pp. 226–227.

^ Runciman 1958, p. 227.

^ Takayama 2004, p. 80.

^ ab Abulafia 2000, p. 97.

^ Dunbabin 1998, pp. 109–110.

^ Runciman 1958, pp. 229–230.

^ ab Runciman 1958, p. 232.

^ ab Bárány 2010, p. 67.

^ Runciman 1958, pp. 235–236.

^ abcde Runciman 1958, p. 236.

^ Bárány 2010, p. 68.

^ Housley 1982, p. 20.

^ Runciman 1958, pp. 236–237.

^ Runciman 1958, p. 241.

^ Runciman 1958, p. 238.

^ Runciman 1958, pp. 238, 244.

^ Runciman 1958, p. 245.

^ Runciman 1958, p. 243.

^ Runciman 1958, p. 246.

^ ab Runciman 1958, p. 247.

^ abcd Runciman 1958, p. 248.

^ abc Runciman 1958, p. 249.

^ abc Runciman 1958, p. 250.

^ Runciman 1958, p. 253.

^ Runciman 1958, pp. 254–255.

^ ab Dunbabin 1998, p. 232.

^ abc Runciman 1958, p. 255.

^ Dunbabin 1998, pp. 9, 232.

^ Dunbabin 2000, pp. 316, 322, 383–384, 389–391.

^ Casas Castells 2007, pp. 78, 108, 112.

^ Nicholas 1992, p. 441.

^ Dunbabin 1998, p. 183.

^ Dunbabin 1998, pp. 181–182.

^ Dunbabin 1998, p. 184.

^ Dunbabin 1998, pp. 183–184.

^ Engel 2001, pp. 107, 109.

^ abc Dunbabin 1998, p. 185.

^ ab Runciman 1958, p. 138.

^ Engel 2001, p. 97.

^ Dunbabin 1998, p. 186.

^ ab Dunbabin 1998, p. 70.

^ Abulafia 2000, pp. 96–97, 102–103.

^ ab Abulafia 2000, p. 104.

^ Dunbabin 1998, p. 59.

^ Dunbabin 1998, pp. 21–22.

^ abc Dunbabin 1998, p. 116.

^ Dunbabin 1998, pp. 114–116.

^ Takayama 2004, p. 79.

^ Dunbabin 1998, p. 119.

^ Dunbabin 1998, pp. 119–120.

^ Dunbabin 1998, p. 121.

^ Dunbabin 1998, p. 125.

^ Dunbabin 1998, pp. 114–115.

^ Dunbabin 1998, p. 220.

^ Dunbabin 1998, p. 215.

^ Dunbabin 1998, pp. 215, 217.

^ ab Dunbabin 1998, p. 222.

^ Patai 1977, p. 156.

^ ab Dunbabin 1998, p. 203.

^ Dunbabin 1998, pp. 203–204.

^ Dunbabin 1998, pp. 205, 207.

^ Dunbabin 1998, pp. 205, 208.

^ Hollander 2004, p. 159.

^ Dunbabin 1998, pp. 210–211.

^ ab Dunbabin 1998, p. 211.

^ Dunbabin 1998, p. 212.

Sources

.mw-parser-output .refbegin{font-size:90%;margin-bottom:0.5em}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ul{list-style-type:none;margin-left:0}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ul>li,.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>dl>dd{margin-left:0;padding-left:3.2em;text-indent:-3.2em;list-style:none}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-100{font-size:100%}

Abulafia, David (2000). "Charles of Anjou reassessed". Journal of Medieval History. 26 (1): 93–114. doi:10.1016/s0304-4181(99)00012-3. ISSN 0304-4181..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

Asbridge, Thomas (2012). The Crusades: The War for the Holy Land. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-1-84983-688-3.

Bárány, Attila (2010). "The English relations of Charles II of Sicily and Maria of Hungary". In Kordé, Zoltán; Petrovics, István. Diplomacy in the Countries of the Angevin Dynasty in the Thirteenth–Fourteenth Centuries. Accademia d'Ungheria in Roma. pp. 57–77. ISBN 978-963-315-046-7.

Casas Castells, Elena (2007). Reyes de España: Desde los Primeros Reyes Godos hasta Hoy [The Kings of Spain: From the First Gothic Kings till Today] (in Spanish). LIBSA. ISBN 84-662-1323-6.

Cox, Eugene L. (1974). The Eagles of Savoy: The House of Savoy in Thirteenth-Century Europe. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-05216-6.

Dunbabin, Jean (1998). Charles I of Anjou. Power, Kingship and State-Making in Thirteenth-Century Europe. Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-1-78093-767-0.

Dunbabin, Jean (2000). France in the Making, 843-1180. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-820846-4.

Engel, Pál (2001). The Realm of St Stephen: A History of Medieval Hungary, 895–1526. I.B. Tauris Publishers. ISBN 1-86064-061-3.

Fine, John V. A (1994). The Late Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Late Twelfth Century to the Ottoman Conquest. The University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0-472-08260-4.

Harris, Jonathan (2014). Byzantium and the Crusades. Longman. ISBN 0-582-25370-5.

Hollander, Robert (2004). "Notes". In Hollander, Jean; Hollander, Robert. Purgatorio, Dante (A verse translation). First Anchor Books. ISBN 0-385-49700-8.

Housley, Norman (1982). The Italian Crusades: The Papal-Angevin Alliance and the Crusades against Christian Lay Powers, 1254-1343. Clarendon Press. ISBN 0-19-821925-3.

Lock, Peter (1995). The Franks in the Aegean, 1204-1500. Longman. ISBN 0-582-05139-8.

Lock, Peter (2006). The Routledge Companion to the Crusades. Routledge. ISBN 9-78-0-415-39312-6.

Metcalfe, Alex (2009). The Muslims of Medieval Italy. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0-7486-2007-4.

Nicol, Donald M. (1984). The Despotate of Epirus, 1267-1479: A Contribution to the History of Greece in the Middle Ages. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-13089-9.

Nicholas, David (1992). Medieval Flanders. Longman. ISBN 0-582-01678-9.

Patai, Raphael (1977). The Jewish Mind. Wayne State University Press. ISBN 0-8143-2651-X.

Runciman, Steven (1958). The Sicilian Vespers: A History of the Mediterranean World in the Later Thirteenth Century. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-60474-2.

Takayama, Hiroshi (2004). "Law and monarchy in the south". In Abulafia, David. Italy in the Central Middle Ages, 1000-1300. Oxford University Press. pp. 58–81. ISBN 0-19-924704-8.

Further reading

Fischer, Klaus Dietrich (1982). "Moses of Palermo: Translator from the Arabic at the Court of Charles of Anjou". Histoires des sciences médicales. 17 (Special 17): 278–281.

Holloway, Julia Bolton (1993). Twice-Told Tales: Brunetto Latino and Dante Aligheri. Peter Lang Inc. ISBN 978-0-82041-954-1.

External links

"Charles of Anjou". New International Encyclopedia. 1905.

"Charles of Anjou". New International Encyclopedia. 1905.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Charles I of Naples. |

Charles I of Anjou Capetian House of Anjou Born: 1227 Died: 7 January 1285 | ||

| Regnal titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Manfred | King of Sicily 1266–1282/1285 | Succeeded by Peter I as king on Sicily from 1282 |

| Succeeded by Charles II as king in Southern Italy from 1285 | ||

New title | King of Albania 1272–1285 | Succeeded by Charles II |

| Preceded by William II | Prince of Achaea 1278–1285 | |

| Preceded by Beatrice | Count of Provence 1246–1285 | |

Vacant Title last held by John | Count of Anjou and Maine 1246–1285 | |

| Preceded by Beatrice I | Count of Forcalquier 1246–1248 | Succeeded by Beatrice II |

| Preceded by Beatrice II | Count of Forcalquier 1256–1285 | Succeeded by Charles II |

| Preceded by | Senator of Rome 1263–1266 | Succeeded by Conrad Monaldeschi Luca Savelli |

| Preceded by Henry of Castile | Senator of Rome 1268–1278 | Succeeded by Matteo Orsini |

| Preceded by Matteo Orsini | Senator of Rome 1281–1285 | Succeeded by |