Manfred, King of Sicily

This article includes a list of references, but its sources remain unclear because it has insufficient inline citations. (February 2012) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

| Manfred | |

|---|---|

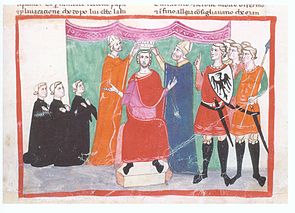

13th-century depiction of writer Johensis presenting Manfred with the Bibbia di Manfredi | |

| King of Sicily | |

| Reign | 1258–1266 |

| Coronation | 10 August 1258 |

| Predecessor | Conradin |

| Successor | Charles I |

| Born | 1232 Venosa, Kingdom of Sicily |

| Died | 26 February 1266 (killed in battle, aged 34) Benevento, Kingdom of Sicily |

| Spouse | Beatrice of Savoy Helena Angelina Doukaina |

| Issue | Constance, Queen of Sicily |

| House | House of Hohenstaufen |

| Father | Frederick II, Holy Roman Emperor |

| Mother | Bianca Lancia |

Manfred (Sicilian: Manfredi di Sicilia; 1232 – 26 February 1266) was the King of Sicily from 1258 to 1266. He was an illegitimate son of the emperor Frederick II of Hohenstaufen,[1] but his mother, Bianca Lancia (or Lanzia), is reported by Matthew Paris to have been married to the emperor while on her deathbed.[2]

Contents

1 Early life

2 Kingship

3 Marriages and children

4 Character and legacy

5 Notes

6 References

7 External links

Early life

Seal of Manfred

Manfred was born in Venosa. Frederick II appears to have regarded him as legitimate, and by his will named him as Prince of Taranto[3] and appointed him as the representative in Italy of his half-brother, the German king, Conrad IV.[2] Manfred, who initially bore his mother's surname, studied in Paris and Bologna and shared with his father a love of poetry and science.

At Frederick's death, Manfred, although only about 18 years old, acted loyally and with vigour in the execution of his trust. The Kingdom was in turmoil, mainly due to riots spurred by Pope Innocent IV. Manfred was able to subdue numerous rebel cities, with the exception of Naples.[4] When his legitimate brother Conrad IV appeared in southern Italy in 1252, disembarking at Siponto, his authority was quickly and generally acknowledged.[2] Naples fell in October 1253 into the hands of Conrad. The latter, in the meantime, had grown distrustful of Manfred, stripping him of all his fiefs and reducing his authority to the principality of Taranto.

In May 1254 Conrad died of malaria.[5] Manfred, after refusing to surrender Sicily to Innocent IV, accepted the regency on behalf of Conradin, the infant son of Conrad.[6] The pope however, having been named guardian of Conradin, excommunicated Manfred in July 1254.[7] The regent decided to open negotiations with Innocent. By a treaty made in September 1254, Apulia passed under the authority of the pope, who was personally conducted by Manfred into his new possession. But Manfred’s suspicions being aroused by the demeanour of the papal retinue, and also annoyed by the occupation of Campania by papal troops, he fled to the Saracens at Lucera. Aided by Saracen allies, he defeated the papal army at Foggia on 2 December 1254,[8] and soon established his authority over Sicily and the Sicilian possessions on the mainland.[2] In that year Manfred supported the Ghibelline communes in Tuscany, in particular Siena, to which he provided a corps of German knights that was later instrumental in the defeat of Florence at the Battle of Montaperti. He thus reached the status of patron of the Ghibelline League. Also in that year Innocent died, succeeded by Alexander IV, who immediately excommunicated Manfred.[6] In 1257, however, Manfred crushed the papal army and settled all the rebellions, imposing his firm rule of southern Italy and receiving the title of vicar from Conradin.

Kingship

Coronation of Manfred at Palermo, 1258

The following year, taking advantage of a rumour that Conradin was dead, he was crowned King of Sicily at Palermo on August 10. The falsehood of this report was soon manifest; but the new king, supported by the popular voice, declined to abdicate and pointed out to Conradin’s envoys the necessity for a strong native ruler. The pope, to whom the Saracen alliance was a serious offence, declared Manfred’s coronation void. Undeterred by the excommunication Manfred sought to obtain power in central and northern Italy, where the Ghibelline leader Ezzelino III da Romano had disappeared. He named vicars in Tuscany, Spoleto, Marche, Romagna and Lombardy. After Montaperti he was recognized as protector of Tuscany by the citizens of Florence, who did homage to his representative, and he was chosen "Senator of the Romans" by a faction in the city.[2] His power was also augmented by the marriage of his daughter Constance in 1262 to Peter III of Aragon.

Terrified by these proceedings, the new Pope Urban IV excommunicated him. The pope first tried to sell the Kingdom of Sicily to Richard of Cornwall and his son, but in vain. In 1263 he was most successful with Charles, the Count of Anjou, a brother of the French King Louis IX, who accepted the investiture of the kingdom of Sicily at his hands. Hearing of the approach of Charles, Manfred issued a manifesto to the Romans, in which he not only defended his rule over Italy but even claimed the imperial crown.[2]

Charles' army, some 30,000 strong, entered Italy from the Col de Tende in late 1265. He soon reduced numerous Ghibelline strongholds in northern Italy and was crowned in Rome in January 1266, the pope being absent. On 20 January he set southwards and waded the Liri river, invading the Kingdom of Sicily. After some minor clashes, the rival armies met at the Battle of Benevento on 26 February 1266, and Manfred's army was defeated.[9] The king himself, refusing to flee, rushed into the midst of his enemies and was killed.[10] Over his body, which was buried on the battlefield, a huge heap of stones was placed, but afterwards with the consent of the pope the remains were unearthed, cast out of the papal territory, and interred on the bank of the Garigliano River, outside of the boundaries of Naples and the Papal States.[2][10]

At the Battle of Benevento Charles captured Helena and imprisoned her. She lived five years later in captivity in the castle of Nocera Inferiore where she died in 1271. Manfred's son-in-law Peter III eventually became King Peter I of Sicily from 1282 after the Sicilian Vespers expelled the French from the island again.

The modern city of Manfredonia was built by King Manfred between 1256–1263, some kilometers north of the ruins of the ancient Sipontum. The Angevines, who had defeated Manfred and stripped him of the Kingdom of Sicily, renamed it Sypontum Novellum ("New Sypontum"), but that name never imposed.

Marriages and children

Manfred was married twice. His first wife was Beatrice,[11] daughter of Amadeus IV, count of Savoy, by whom he had a daughter, Constance, who was married to the heir to the Aragonese throne, the future King Peter III of Aragon, on 13 June 1262.[12]

Manfred's second wife was Helena Angelina Doukaina,[11] daughter of Michael II Komnenos Doukas, ruler of the despotate of Epirus, who made this marriage to ally with Manfred after being attacked by him at Thessalonica. Helena and Manfred had four children: Beatrix, Frederick, Henry and Azzolino. Helena and all her children were captured by Charles of Anjou after Manfred's death in 1266.[13] Helena died in prison in Nocera in 1271. The children were imprisoned in the Castel dell'Ovo until they were moved to the Castel Nuovo by Charles II in 1299. Azzolino died first, followed by Henry in 1309. Beatrice had been released on the orders of the Aragonese commander Roger of Lauria following a battle off Naples in 1284. She went on to marry Manfred IV, Marquis of Saluzzo.[14] The eldest son, Frederick, escaped his prison and fled to Germany. He spent time in several European courts before dying in Egypt in 1312.[13][15]

Manfred had at least one illegitimate child, a daughter named Flordelis.[13]

Character and legacy

Manfred holding a falcon from the 13th-century De arte venandi cum avibus

Contemporaries praised the noble and magnanimous character of Manfred, who was renowned for his physical beauty and intellectual attainments.[2] In the Divine Comedy, Dante meets Manfred outside the gates of Purgatory, where the spirit explains that, although he repented of his sins in articulo mortis, he must atone for his contumacy by waiting 30 years for each year he lived as an excommunicate, before being admitted to Purgatory proper.

Manfred formed the subject of dramas by E.B.S. Raupach, O. Marbach and F.W. Roggee. Three letters written by Manfred were published by J. B. Carusius in Bibliotheca historica regni Siciliae (Palermo, 1732).[2]

Manfred's name was borrowed by the English author Horace Walpole for the main character of his short novel The Castle of Otranto (1764). Montague Summers, in his 1924 edition of this work, showed that some details of Manfred of Sicily's real history inspired the novelist. The name was re-borrowed by Lord Byron for his dramatic poem Manfred (1817).

Notes

^ Malcolm Barber, The Two Cities: Medieval Europe 1050–1320, 2nd edition, (Routledge, 2004), 233.

^ abcdefghi One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Manfred, King of Sicily". Encyclopædia Britannica. 17 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 568..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Manfred, King of Sicily". Encyclopædia Britannica. 17 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 568..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ Steven Runciman, The Sicilian Vespers, (Cambridge University Press, 1958), 27.

^ Steven Runciman, The Sicilian Vespers, 28-29.

^ Johannes Fried, The Middle Ages, transl. Peter Lewis, (Harvard University Press, 2015), 282.

^ ab J.N.D. Kelly and M.J. Walsh, Alexander IV, A Dictionary of Popes, (Oxford University Press, 1986), 195.

^ Manfred, John Lomax, Key Figures in Medieval Europe: An Encyclopedia, ed. Richard K. Emmerson, (Taylor & Francis, 2006), 440.

^ Roy Palmer Domenico, The Regions of Italy: A Reference Guide to History and Culture, (Greenwood Publishing, 2002), 25.

^ Steven Runciman, The Sicilian Vespers, 92, 94.

^ ab Steven Runciman, The Sicilian Vespers, 94

^ ab Steven Runciman, The Sicilian Vespers, 43.

^ Guida Myrl Jackson-Laufer, Women Rulers Throughout the Ages: An Illustrated Guide, (ABC-CLIO, 1999), 107.

^ abc Walter Koller, "Manfredi, re di Sicilia", Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani, vol. 68 (Rome: 2007).

^ Ferdinand Gregorovius, History of the City of Rome in the Middle Ages, vol. 5, part 2 (Cambridge University Press, 2010 [1897]), p. 537, n. 1

^ Alfred Haverkamp, Medieval Germany, 1056–1273 (Oxford University Press, 1988), p. 267.

References

Momigliano, Eucardio (1963). Manfredi. Milan: Dell'Oglio.

Mendola, Louis (2016). The Chronicle of Nicholas of Jamsilla. New York: Trinacria.

External links

Markus Brantl: Regesten und Itinerar König Manfreds von Sizilien, 2005 (XML-version, pdf-version, 6 MB)(in German)

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Manfred, King of Sicily. |

| Regnal titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Conradin | King of Sicily 1258–1266 | Succeeded by Charles I |