Anastasian War

| Anastasian War | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Roman-Persian Wars | |||||||||

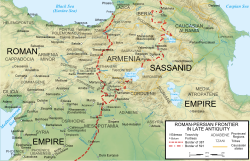

The Roman-Persian frontier had remained stable since 384, when the two powers divided Armenia, and despite recurrent warfare, would not change significantly until the Lazic War. | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

Eastern Roman Empire | Sassanid Empire Lakhmids | ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

Anastasius I Rufinus Areobindus Patricius Patriciolus Vitalian Hypatius Pharesmanes Celer Romanus Timostratus Constantine (POW)[2] | Kavadh I Theodore Al-Mundhir III ibn al-Nu'man Adergoudounbades Bawi Glones Mirranes? | ||||||||

The Anastasian War was fought from 502 to 506 between the Eastern Roman Empire and the Sassanid Empire. It was the first major conflict between the two powers since 440, and would be the prelude to a long series of destructive conflicts between the two empires over the next century.

Contents

1 Prelude

2 War

3 Aftermath

4 References

5 Sources

5.1 Primary

5.2 Secondary

Prelude

Several factors underlay the termination of the longest period of peace the Eastern Roman and the Sassanid Empire ever enjoyed. The Persian king Kavadh I needed money to pay his debts to the Hephthalites who had helped him regain his throne in 498/499. The situation was exacerbated by recent changes in the flow of the Tigris in Lower Mesopotamia, sparking famines and flood. When the Roman emperor Anastasius I refused to provide any help, Kavadh tried to gain the money by force.[3]

War

In 502, Kavadh quickly captured the unprepared city of Theodosiopolis, perhaps with local support; the city was in any case undefended by troops and weakly fortified.[4] Kavadh then besieged the fortress-city of Amida through the autumn and winter (502-503). The siege of the city proved to be a far more difficult enterprise than Kavadh expected; the defenders, although unsupported by troops, repelled the Persian assaults for three months before they were finally beaten.[5] The year 503 saw much warfare without decisive results: the Romans attempted an ultimately unsuccessful siege of the Persian-held Amida while Kavadh invaded Osroene, and laid siege to Edessa with the same results.[6]

Roman and Persian Empires in 500, also showing their neighbors, many of whom were dragged into wars between the great powers.

Finally in 504, the Romans gained the upper hand with the renewed investment of Amida leading to the hand-over of the city. That year, an armistice was agreed as a result of an invasion of Armenia by the Huns from the Caucasus. Negotiations between the two powers took place, but such was the distrust that in 506 the Romans, suspecting treachery, seized the Persian officials; once released, the Persians preferred to stay in Nisibis.[7] In November 506, a treaty was finally agreed, but little is known of what the terms of the treaty were. Procopius states that peace was agreed for seven years, and it is likely that some payments were made to the Persians.[8]

Aftermath

The Roman generals blamed many of their difficulties in this war on their lack of a major base in the immediate vicinity of the frontier, a role filled for the Persians by Nisibis (which until its secession in 363 had served the same purpose for the Romans), and in 505 Anastasius therefore ordered the building of a great fortified city at Dara. The dilapidated fortifications were also upgraded at Edessa, Batnae and Amida.[9]

Although no further large-scale conflict took place during Anastasius's reign, tensions continued, especially while work continued at Dara. This construction project was to become a key component of the Roman defenses, and also a lasting source of controversy with the Persians, who complained that its construction violated the treaty agreed in 422, by which both empires had agreed not to establish new fortifications in the frontier zone. Anastasius, however, pursued the project, deflecting Kavadh's complaints with money. The Persians were in any case unable to stop the work, and the walls were completed by 507/508.[7]

References

^ ab http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/sasanian-dynasty

^ The sources are contradictory about the role played by Constantine during the siege of Theodosiopolis. According to Zacharias Rhetor, (Greatrex 2002, p. 63) he was taken prisoner, while according to Joshua the Stylite, due a grudge he bore against the emperor Anastasius, he betrayed the Romans.(Martindale 1980, p. 314)

^ Procopius. History of the Wars, I.7.1-2; Greatrex & Lieu 2002, p. 62.

^ Greatrex & Lieu 2002, p. 62.

^ Greatrex & Lieu 2002, p. 63.

^ Greatrex & Lieu 2002, pp. 69–71.

^ ab Greatrex & Lieu 2002, p. 77.

^ Procopius. History of the Wars, I.9.24; Greatrex & Lieu 2002, p. 77.

^ Greatrex & Lieu 2002, p. 74.

Sources

Primary

.mw-parser-output .refbegin{font-size:90%;margin-bottom:0.5em}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ul{list-style-type:none;margin-left:0}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ul>li,.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>dl>dd{margin-left:0;padding-left:3.2em;text-indent:-3.2em;list-style:none}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-100{font-size:100%}

Procopius; Dewing, H. B. (trans.). History of the Wars..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

Books I–II.

Secondary

Greatrex, Geoffrey; Lieu, Samuel N. C. (2002). The Roman Eastern Frontier and the Persian Wars (Part II, 363–630 AD). New York, New York and London, United Kingdom: Routledge (Taylor & Francis). ISBN 0-415-14687-9.