Barents Sea

| Barents Sea | |

|---|---|

Location of the Barents Sea | |

| Location | Arctic Ocean |

| Coordinates | 75°N 40°E / 75°N 40°E / 75; 40 (Barents Sea)Coordinates: 75°N 40°E / 75°N 40°E / 75; 40 (Barents Sea) |

| Type | Sea |

| Primary inflows | Norwegian Sea, Arctic Ocean |

Basin countries | Norway and Russia |

| Surface area | 1,400,000 km2 (540,000 sq mi) |

| Average depth | 230 m (750 ft) |

| References | Institute of Marine Research, Norway |

The Barents Sea (Norwegian: Barentshavet; Russian: Баренцево море, Barentsevo More) is a marginal sea of the Arctic Ocean,[1] located off the northern coasts of Norway and Russia and is divided between Norwegian and Russian territorial waters.[2] Known among Russians in the Middle Ages as the Murman Sea ("Norwegian Sea"), the sea takes its current name from the Dutch navigator Willem Barentsz.

It is a rather shallow shelf sea, with an average depth of 230 metres (750 ft), and is an important site for both fishing and hydrocarbon exploration.[3] The Barents Sea is bordered by the Kola Peninsula to the south, the shelf edge towards the Norwegian Sea to the west, and the archipelagos of Svalbard to the northwest, Franz Josef Land to the northeast and Novaya Zemlya to the east. The islands of Novaya Zemlya, an extension of the northern end of the Ural Mountains, separate the Barents Sea from the Kara Sea.

Despite being part of the Arctic Ocean, the Barents Sea has been characterized as "turning into the Atlantic" because of its status as "the Arctic warming hot spot." Hydrologic changes due to global warming have led to a reduction in sea ice and in stratification of the water column, which could lead to major changes in weather in Eurasia.[4]

Contents

1 Geography

1.1 Extent

2 Geology

3 Ecology

4 History

4.1 Name

4.2 Modern era

5 Economy

5.1 Political status

5.2 Oil and gas

5.3 Fishing

5.4 Barents Sea biodiversity and marine bioprospecting

5.4.1 Institutions and industry supporting marine bioprospecting in Barents Sea

6 See also

7 Notes

8 References

9 External links

Geography

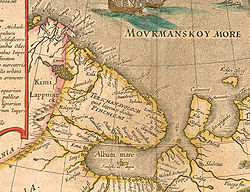

Shores of the Barents (Murman) Sea. From "Tabula Russiae", Joan Blaeu's, Amsterdam, 1614.

The southern half of the Barents Sea, including the ports of Murmansk (Russia) and Vardø (Norway) remain ice-free year round due to the warm North Atlantic drift. In September, the entire Barents Sea is more or less completely ice-free. Until the Winter War (1939–40), Finland's territory also reached to the Barents Sea, with the harbor at Petsamo being Finland's only ice-free winter harbor.

There are three main types of water masses in the Barents Sea: Warm, salty Atlantic water (temperature >3 °C, salinity >35) from the North Atlantic drift, cold Arctic water (temperature <0 °C, salinity <35) from the north, and warm, but not very salty coastal water (temperature >3 °C, salinity <34.7). Between the Atlantic and Polar waters, a front called the Polar Front is formed. In the western parts of the sea (close to Bear Island), this front is determined by the bottom topography and is therefore relatively sharp and stable from year to year, while in the east (towards Novaya Zemlya), it can be quite diffuse and its position can vary a lot between years.

The lands of Novaya Zemlya attained most of their early Holocene coastal deglaciation approximately 10,000 years before present.[5]

Extent

The International Hydrographic Organization defines the limits of the "Barentsz Sea" [sic] as follows:[6]

On the west: The northeastern limit of the Norwegian Sea [A line joining the southernmost point of West Spitzbergen [sic] to North Cape of Bear Island, through this island to Cape Bull and thence on to North Cape in Norway (25°45'E)].

On the northwest: The eastern shore of West Spitzbergen [sic], Hinlopen Strait up to 80° latitude north; south and east coasts of North-East Land [island of Nordaustlandet] to Cape Leigh Smith (80°05′N 28°00′E / 80.083°N 28.000°E / 80.083; 28.000).

On the north: Cape Leigh Smith across the Islands Bolshoy Ostrov (Great Island) [Storøya], Gilles [Kvitøya] and Victoria; Cape Mary Harmsworth (southwestern extremity of Alexandra Land) along the northern coasts of Franz-Josef Land as far as Cape Kohlsaat (81°14′N 65°10′E / 81.233°N 65.167°E / 81.233; 65.167).

On the east: Cape Kohlsaat to Cape Zhelaniya (Desire); west and southwest coast of Novaya Zemlya to Cape Kussov Noss and thence to western entrance Cape, Dolgaya Bay (70°15′N 58°25′E / 70.250°N 58.417°E / 70.250; 58.417) on Vaigach Island. Through Vaigach Island to Cape Greben; thence to Cape Belyi Noss on the mainland.

On the south: The northern limit of the White Sea [A line joining Svyatoi Nos (Murmansk Coast, 39°47'E) and Cape Kanin].

Other islands in the Barents Sea include Chaichy and Timanets.

Geology

The Barents Sea was originally formed from two major continental collisions: the Caledonian orogeny, in which the Baltica and Laurentia collided to form Laurasia, and a subsequent collision between Laurasia and Western Siberia. Most of its geological history is dominated by extensional tectonics, caused by the collapse of the Caledonian and Uralian orogenic belts and the break-up of Pangaea.[7] These events created the major rift basins that dominate the Barents Shelf, along with various platforms and structural highs. The later geological history of the Barents Sea is dominated by Late Cenozoic uplift, particularly that caused by Quaternary glaciation, which has resulted in erosion and deposition of significant sediment.[8]

Ecology

Phytoplankton bloom in the Barents Sea. The milky-blue colour that dominates the bloom suggests that it contains large numbers of coccolithophores.

Due to the North Atlantic drift, the Barents Sea has a high biological production compared to other oceans of similar latitude. The spring bloom of phytoplankton can start quite early close to the ice edge, because the fresh water from the melting ice makes up a stable water layer on top of the sea water. The phytoplankton bloom feeds zooplankton such as Calanus finmarchicus, Calanus glacialis, Calanus hyperboreus, Oithona spp., and krill. The zooplankton feeders include young cod, capelin, polar cod, whales, and little auk. The capelin is a key food for top predators such as the north-east Arctic cod, harp seals, and seabirds such as common guillemot and Brunnich's guillemot. The fisheries of the Barents Sea, in particular the cod fisheries, are of great importance for both Norway and Russia.

SIZEX-89 was an international winter experiment where the main objectives were to perform sensor signature studies of different ice types in order to develop SAR algorithms for ice variables such as ice types, ice concentrations and ice kinematics.[9]

Although previous research suggested that predation by whales may be the cause of depleting fish stocks, more recent research suggests that marine mammal consumption has only a trivial influence on fisheries and a model examining the impact of fisheries and climate was far more accurate at describing trends in fish abundance.[10] There is a genetically distinct polar bear population associated with the Barents Sea.[11]

History

Dutch whalers near Svalbard, 1690

Name

The Barents Sea was formerly known to Russians as Murmanskoye Morye, or the "Sea of Murmans" (i.e., Norwegians), and it appears with this name in sixteenth-century maps, including Gerard Mercator's Map of the Arctic published in his 1595 atlas. Its eastern corner, in the region of the Pechora River's estuary, has been known as Pechorskoye Morye, that is, Pechora Sea.

This sea was given its present name in honor of Willem Barentsz, a Dutch navigator and explorer. Barentsz was the leader of early expeditions to the far north, at the end of the sixteenth century.

The Barents Sea has been called by sailors "The Devil's Dance Floor" due to its unpredictability and difficulty level.[12]

The Barents Sea has been called by ocean rowers "Devil's Jaw". In 2017 after the first recorded complete man-powered crossing of the Barents Sea from Tromsø to Longyearbyen in a row boat in 2017 by Polar Row expedition, captain Fiann Paul was asked by Norwegian TV2 how a rower would name the Barents Sea. Fiann responded that he would name it “Devil's Jaw”, adding that the winds you constantly battle are like breathe from the devil's nostrils while he holds you in his jaws.[13]

The harbour of the Murmansk Fjord.

Modern era

Seabed mapping was completed in 1933 with the first full map produced by Russian marine geologist Maria Klenova.

The Barents Sea was also the site of a notable World War II engagement, a German surface merchant raiding attack on a British convoy that later became known as the Battle of the Barents Sea. Under the command of Oskar Kummetz, the German warships sank minelayer HMS Bramble and destroyer HMS Achates, but in turn lost destroyer Z16 Friedrich Eckoldt and Admiral Hipper was severely damaged by British gunfire. The Germans later retreated and the British convoy arrived safely at Murmansk shortly afterwards.

During the Cold War, the Soviet Red Banner Northern Fleet used the southern reaches of the sea as a ballistic missile submarine bastion, a strategy that Russia continues. Nuclear contamination from dumped Russian naval reactors is an environmental concern in the Barents Sea.

Economy

Political status

Signing of the Russian-Norwegian Treaty, 15 September 2010

For decades there was a boundary dispute between Norway and Russia regarding the position of the boundary between their respective claims to the Barents Sea. The Norwegians favoured a median line, based on the Geneva Convention of 1958, whereas the Russians favoured a meridian based sector line, based on a Soviet decision of 1926.[7] This led to a neutral "grey" zone between the competing claims that had an area of 175,000 sq.km, which is approximately 12% of the total area of the Barents Sea. The two countries started negotiations on the location of the boundary in 1974 and a moratorium on hydrocarbon exploration was declared in 1976.

In 2010, Norway and Russia signed an agreement that placed the boundary equidistant from their competing claims. This was ratified and went into force on 7 July 2011, opening the grey zone for hydrocarbon exploration.[14]

Oil and gas

Encouraged by the success of the North Sea in the 1960s, hydrocarbon exploration in the Barents Sea got underway in 1969. The Norwegian authorities acquired seismic reflection surveys through the following years, which were analysed to understand the location of the main sedimentary basins.[7]NorskHydro drilled the first well in 1980, which was a dry hole, and the first discoveries were made the following year – the Alke and Askeladden gas fields.[7] Several more discoveries were made on the Norwegian side of the Barents Sea throughout the 1980s, including the important Snøhvit field.[15] However interest in the area began to wane due to a succession of dry holes, the wells only containing gas (which was cheap at the time) and the prohibitive costs of developing wells in such a remote area. Interest in the area was reignited in the late 2000s, after the Snovhit field was finally bought into production[16] and two new large discoveries were made.[17]

Exploration on the Russian side got underway around the same time as that on Norwegian side, encouraged by the success in the Timan-Pechora Basin.[7] The first wells were drilled in the early 1980s and some very large gas fields were discovered throughout this decade. The Shtokman field was discovered in 1988 and is classed as a giant gas field—currently the 5th largest gas field in the world. However, due to the same reasons that interest declined in the Norwegian side of the Barents Sea, in addition to the political instability of the 1990s, interest in the Russian side of the Barents Sea declined.

Fishing

Honningsvåg is the most northerly fishing village in Norway

The Barents Sea contains the world largest remaining cod population,[18] as well as an important stocks of haddock and capelin. Fishing is managed jointly by Russia and Norway in the form of the Joint Norwegian–Russian Fisheries Commission, established in 1976, in an attempt to keep track of how many fish are leaving the ecosystem due to fishing.[19] The Joint Norwegian-Russian Fisheries Commission sets Total Allowable Catches (TACs) for multiple species throughout their migratory tracks. Through the Commission, Norway and Russia also exchange fishing quotas and catch statistics to ensure the TACs are not being violated. However, there are problems with the system and the effects of fishing on the Barents Sea ecosystem are not completely accurate. Cod is one of the major catches. A large portion of catches are not reported when the fishing boats land to account for profits that are being lost to high taxes and fees. Since many fishermen do not strictly follow the TACs and rules set forth by the Commission, the amount of fish being extracted annually from the Barents Sea is underestimated.

Barents Sea biodiversity and marine bioprospecting

The Barents Sea, where temperate waters from the Gulf Stream and cold waters from the Arctic meet, is home to an enormous diversity of organisms, which are well adapted to the extreme conditions of their marine habitats. This makes these arctic species very attractive for marine bioprospecting. Marine bioprospecting may be defined as the search for bioactive molecules and compounds from marine sources having new, unique properties and the potential for commercial applications. Amongst others, applications include medicines, food and feed, textiles, cosmetics and the process industry.

The Norwegian government strategically supports the development of marine bioprospecting as it has the potential to contribute to new and sustainable wealth creation. Tromsø and the northern areas of Norway play a central role in this strategy due to excellent access to unique Arctic marine organisms and the presence of marine industries and R&D competence and infrastructure in this region. Since 2007, science and industry have cooperated closely on bioprospecting and the development and commercialization of new products.[20]

Institutions and industry supporting marine bioprospecting in Barents Sea

MabCent-SFI is one of fourteen Research-Based Innovation Centers initiated by the Research Council of Norway, and is the only one within the field of “bioactive compounds and drug discovery” that is based on bioactives from marine organisms. MabCent-SFI maintains a focus on bioactives from Arctic and sub-Arctic organisms. By the end of 2011, MabCent has tested about 200,000 extracts, finding several hundred "hits". Through further research and development, some of these hits will become valuable "leads", i.e. characterized compounds known to possess biological effects of interest.

The commercial partners in MabCent-SFI are Biotec Pharmacon ASA and its subsidiary ArcticZymes AS, ABC BioScience AS, Lytix Biopharma AS and Pronova BioPharma ASA. ArcticZymes is also a partner in MARZymes, a project financed by the Research Council of Norway to find marine enzymes which are adapted to the extreme conditions in the Arctic. The science partners in MabCent-SFI are Marbank, a national marine biobank located in Tromsø, Marbio, a medium/high-throughput platform for screening and identification of bioactive compounds and Norstruct, a protein structure determination platform. Mabcent-SFI is hosted by the University of Tromsø.

BioTech North is an emerging biotechnology cluster of enterprises and R&D organizations, which cooperate closely with regional funding and development actors (triple helix). As bioactive molecules and compounds from Arctic marine resources form the basis of activities for the majority of the cluster members, BioTech North serves as a marine biotech cluster. The majority of BioTech North’s enterprises are active within life science applications and markets. To date the cluster contains around thirty organizations from both the private and public sector. It has received Arena status and is funded through the [ Arena] programme financed by Innovation Norway, SIVA and The Research Council of Norway. Stakeholders of BioTech North include Barents BioCentre Lab, BioStruct, Marbank, Norut, Nofima, Mabcent-SFI, University of Tromsø, Unilab, Barentzymes AS, Trofi, Scandiderma AS, Prophylix Pharma AS, Olivita, Marealis, ProCelo, Probio, Lytix Biopharma, Integorgen, d'Liver, Genøk, Cognis, Clare AS, Chitinor, Calanus AS, Biotec Betaglucans, Ayanda, ArcticZymes AS, ABC Bioscience, Akvaplanniva.

See also

- Barents Basin

- Continental shelf of Russia

- Energy in Norway

- List of largest biotechnology & pharmaceutical companies

- List of oil and gas fields of the Barents Sea

- List of seas

Notes

^ John Wright (30 November 2001). The New York Times Almanac 2002. Psychology Press. p. 459. ISBN 978-1-57958-348-4. Retrieved 29 November 2010..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ World Wildlife Fund, 2008.

^ O. G. Austvik, 2006.

^ Mooney, Chris (2018-06-26). "A huge stretch of the Arctic Ocean is rapidly turning into the Atlantic. That's not a good sign". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 2018-06-27.

^ J. Zeeberg, 2001.

^ "Limits of Oceans and Seas, 3rd edition" (PDF). International Hydrographic Organization. 1953. Retrieved 6 February 2010.

^ abcde Doré, A.G. (Sep 1995). "Barents Sea Geology, Petroleum Resources and Commercial Potential" (PDF). 48 (3). Arctic Institute of North America.

^ Doré, A.G. (March 1996). "Impact of Glaciations on Basin Evolution: Data and Models from the Norwegian Margin and Adjacent Areas". 12 (1–4). Global and Planetary Change.

^ Sea ice modeling in the Barents Sea during SIZEX 89 (Haugan, P.M., Johannessen, O.M. and Sandven, S., IGARSS´90 symposium, Washington D.C., 1990)

^ Corkeron, Peter J. (April 23, 2009). "Marine mammals' influence on ecosystem processes affecting fisheries in the Barents Sea is trivial". Biology Letters. The Royal Society. 5 (2): 204–206. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2008.0628. ISSN 1744-957X. PMC 2665811. PMID 19126534. Retrieved 30 June 2009.

^ C.M. Hogan, 2008

^ Administrator, journallive (2006-08-15). "Warming to cap art". journallive. Retrieved 2017-10-05.

^ AS, TV 2. "Tor (36) nådde Svalbard på supertid, this is the link to the news summary, full video news was broadcast on 29 July in the News section, available on youtube". TV 2 (in Norwegian). Retrieved 2017-10-05.

^ Amos, Howard (7 July 2011). "Arctic Treaty With Norway Opens Fields". The Moscow Times. Retrieved 2 July 2014.

^ "Snøhvit Gas Field, Norway". Offshore Technology. Retrieved 2 July 2014.

^ "Snøhvit". Statoil Website. Retrieved 2 July 2014.

^ "Norway Makes Its Second Huge Oil Discovery In The Past Year". Associated Press. January 9, 2012.a well drilled in the Havis prospect in the Barents Sea proved both oil and gas at an estimated volume of between 200 million and 300 million barrels of recoverable oil equivalents.

^ "The Barents Sea Cod – the last of the large cod stocks". World Wildlife Foundation. Retrieved 4 July 2014.

^ ""The History of the Joint Norwegian-Russian Fisheries Commission"".

^ Nasjonal Strategi 2009. "Marin bioprospektering – en kilde til ny og bærekraftig verdiskaping" (PDF).

References

- Ole Gunnar Austvik (2006) Oil and gas in the High North, Security Policy Library no. 4, The Norwegian Atlantic Committee. ISSN 0802-6602.

- C. Michael Hogan (2008) Polar Bear: Ursus maritimus, Globaltwitcher.com, ed. Nicklas Stromberg.

- World Wildlife Fund (2008). Barents Sea environment and conservation.

Zeeberg, JaapJan; David J. Lubinski; Steven L. Forman (September 2001). "Holocene Relative Sea Level History of Novaya Zemlya, Russia and Implications for Late Weichselian Ice-Sheet Loading" (PDF). Quaternary Research. Quaternary Research Center/Elsevier Science. 56 (2): 218–230. Bibcode:2001QuRes..56..218Z. doi:10.1006/qres.2001.2256. ISSN 0033-5894.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Barents Sea. |

"Barents Sea". Encyclopædia Britannica. 3 (11th ed.). 1911.

"Barents Sea". Encyclopædia Britannica. 3 (11th ed.). 1911.

Barents.com—Developing the Barents Region

Foraminifera of the Barents Sea—illustrated catalog