Menkaure

| Menkaure | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Menkaura, Mykerinos, Menkheres | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

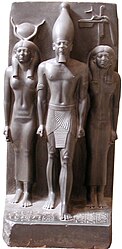

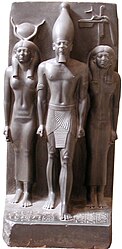

Greywacke statue of Menkaure, Egyptian Museum, Cairo. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Pharaoh | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Reign | 18 to 22 years,[1] starting c. 2530 BC (4th dynasty) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Predecessor | Khafra (most likely) or Bikheris | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Successor | Shepseskaf | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Royal titulary

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Consort | Khamerernebty II, Rekhetre ? | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Children | Khuenre, Shepseskaf, Khentkaus I ?, Sekhemre | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Father | Khafra | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mother | Khamerernebty I | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Born | 2532 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Died | ca. 2500 BC | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Burial | Pyramid of Menkaure | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Menkaure (also Menkaura, Egyptian transliteration mn-k3w-Rˁ), was an ancient Egyptian king (pharaoh) of the 4th dynasty during the Old Kingdom, who is well known under his Hellenized names Mykerinos (Greek: Μυκερίνος) (by Herodotus) and Menkheres (by Manetho). According to Manetho, he was the throne successor of king Bikheris, but according to archaeological evidences he rather was the successor of king Khafre. Menkaure became famous for his tomb, the Pyramid of Menkaure, at Giza and his beautiful statue triads, showing the king together with his wives Rekhetre and Khamerernebty.

Contents

1 Family

2 Reign

3 Pyramid complex

3.1 Valley Temple

3.2 Mortuary Temple

3.3 Sarcophagus

4 Records from later periods

5 Trivia

6 Gallery of images

7 References

8 External links

Family

Menkaure was the son of Khafra and the grandson of Khufu. A flint knife found in the mortuary temple of Menkaure mentioned a king's mother Khamerernebty I, suggesting that Khafra and this queen were the parents of Menkaure. Menkaure is thought to have had at least two wives.

- Queen Khamerernebty II is the daughter of Khamerernebti I and the mother of a king's son Khuenre. The location of Khuenre's tomb suggests that he was a son of Menkaure, making his mother the wife of this king.[2][3]

- Queen Rekhetre is known to have been a daughter of Khafra and as such the most likely identity of her husband is Menkaure.[2]

Not many children are attested for Menkaure:

Khuenre was the son of queen Khamerernebti II. Menkaure was not succeeded by Prince Khuenre, his eldest son, who predeceased Menkaure, but rather by Shepseskaf, a younger son of this king.[4]

Shepseskaf was the successor to Menkaure and likely his son.- Sekhemre is known from a statue and possibly a son of Menkaure.

- A daughter that died in early adulthood is mentioned by Herodotus. She was placed at a superbly decorated hall of the palatial area at Sais, in a hollow gold layered wooden zoomorphic burial feature in the shape of a kneeling cow covered externally with a layer of red decoration except the neck area and the horns which were covered with adequate layers of gold.[5]

Khentkaus I – possible Menkaure's daughter[6]

The royal court included several of Menkaure's half brothers. His brothers Nebemakhet, Duaenre, Nikaure and Iunmin served as vizier during the reign of their brother. His brother Sekhemkare may have been younger and became vizier after the death of Menkaure.[7]

Reign

The length of Menkaure's reign is uncertain. The ancient historian Manetho credits him with rulership of 63 years, but this is surely an exaggeration. The Turin Canon is damaged at the spot where it should present the full sum of years, but the remains allow a reconstruction of "..?.. + 8 years of rulership". Egyptologists think that 18-year rulership was meant to be written, which is generally accepted. A contemporary workmen's graffito reports about the "year after the 11th cattle count". If the cattle count was held every second year (as was tradition at least up to king Sneferu), Menkaure might have ruled for 22 years.[8]

In 2013, a fragment of the sphinx of Menkaure was discovered at Tel Hazor at the entrance to the city palace.[9]

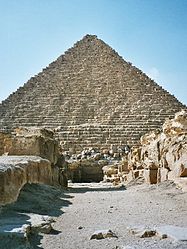

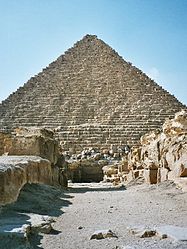

Pyramid complex

Menkaure's pyramid at Giza was called Netjer-er-Menkaure which means "Menkaure is Divine". This pyramid is the smallest of the three pyramids at Giza. This pyramid measures 103.4 meters at the base and 65.5 meters in height.[10] There are three subsidiary pyramids associated with Menkaure's pyramid.

These pyramids are sometimes labeled G-IIIa (East subsidiary pyramid), G-IIIb (Middle subsidiary pyramid) and G-IIIc (West subsidiary pyramid). In the chapel associated with G-IIIa a statue of a Queen was found. It is possible that these pyramids were meant for the Queens of Khafra. It may be that Khamerernebti II was buried in one of the pyramids.[3][7]

Valley Temple

The Valley temple was a mainly brick built structure which was enlarged in the 5th or 6th dynasty. From this temple come the famous statues of Menkaure with his Queen and Menkaure with several deities. A partial list includes:[7]

- Nome triad, Hathor-Mistress-of-the-Sycomore seated, and King and Hare-nome goddess standing, greywacke, in Boston Mus. 09.200.

- Nome triad, King, Hathor-Mistress-of-the-Sycomore and Theban nome-god standing, greywacke. (Now in Cairo Mus. Ent. 40678.)

- Nome triad, King, Hathor-Mistress-of-the-Sycomore and Jackal-nome goddess standing, greywacke. (Now in Cairo Mus. Ent. 40679.)

- Nome triad, King, Hathor-Mistress-of-the-Sycomore and Bat-fetish nome -goddess standing, greywacke. (Now in Cairo Mus. Ent. 46499.)

- Nome triad, King, Hathor, and nome-god standing, greywacke. (Middle part in Boston Mus. 11.3147, head of King in Brussels, Mus. Roy. E. 3074.)

- Double-statue,’ King and wife (Khamerernebti II) standing, uninscribed, greywacke. (Now in Boston Mus. 11.1738.)

- King seated, life-size, fragmentary, alabaster. (Now in Cairo Mus. Ent. 40703.)

- King seated, lower part, inscribed seat, alabaster. (Now in Boston Mus. 09.202)

Mortuary Temple

At this temple more statues and statue fragments were found. An interesting find is a fragment of a wand from Queen Khamerernebty I. The piece is now in the Boston Museum of Fine Arts. Khamerernebti is given the title King's Mother on the fragment.[7]

Sarcophagus

@media all and (max-width:720px){.mw-parser-output .tmulti>.thumbinner{width:100%!important;max-width:none!important}.mw-parser-output .tmulti .tsingle{float:none!important;max-width:none!important;width:100%!important;text-align:center}}

In 1837, English army officer Richard William Howard Vyse, and engineer John Shae Perring began excavations within the pyramid of Menkaure. In the main burial chamber of the pyramid they found a large stone sarcophagus 8 feet 0 inches (244 cm) long, 3 feet 0 inches (91 cm) in width, and 2 feet 11 inches (89 cm) in height, made of basalt. The sarcophagus was uninscribed with hieroglyphs although it was decorated in the style of palace facade. Adjacent to the burial chamber were found wooden fragments of a coffin bearing the name of Menkaure and a partial skeleton wrapped in a coarse cloth. The sarcophagus was removed from the pyramid and was sent by ship to the British Museum in London, but the merchant ship Beatrice carrying it was lost after leaving port at Malta on October 13, 1838. The other materials were sent by a separate ship, and the materials now reside at the museum, with the remains of the wooden coffin case on display.

It is now thought that the coffin was a replacement made during the much later Saite period, nearly two millennia after the pharaoh's original interment. Radio carbon dating of the bone fragments that were found place them at an even later date, from the Coptic period in the first centuries AD.[11]

Records from later periods

According to Herodotus, Menkaure was the son of Khufu (Greek Cheops), and alleviated the suffering his father's reign had caused the inhabitants of ancient Egypt. Herodotus adds that he suffered much misfortune: his only daughter, whose corpse was interred in a wooden bull (which Herodotus claims survived to his lifetime), died before him; additionally, the oracle at Buto predicted he would only rule six years, but through his shrewdness, Menkaure was able to rule a total of 12 years and foil the prophecy (Herodotus, Histories, 2.129-133).

Trivia

- Menkaure was the subject of a poem by the nineteenth century English poet Matthew Arnold, entitled "Mycerinus".

- Menkaure, using the Greek version of his name, Mencheres, is a major character in the Night Huntress series of books by Jeaniene Frost, depicted as an extremely old and powerful vampire. He is a protagonist of one book in the series.

Gallery of images

Colossal alabaster statue of Menkaura at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts

Greywacke statue of Menkaura and Queen Khamerernebty II at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts.

Menkaure's Pyramid in Giza.

Menkaura flanked by the goddess Hathor (left) and a nome goddess Bat (right). Graywacke statue in Cairo Museum.

Fragmentary statue triad of Menkaura flanked by the goddess Hathor (left) and a male nome god (right), Boston Museum of Fine Arts.

Fragmentary alabaster statue head of Menkaura at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts.

Drawing of the anthropoid coffin fragment inscribed with the name of the pharaoh Menkaura made by excavator Richard Vyse and published in 1840.

Menkaura alongside Hathor and the deified nome Anput

References

^ ab Thomas Schneider: Lexikon der Pharaonen. Albatros, Düsseldorf 2002, .mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

ISBN 3-491-96053-3, page 163–164.

^ ab Grajetzki, Ancient Egyptian Queens: A Hieroglyphic Dictionary, Golden House Publications, London, 2005, p13-14

ISBN 978-0-9547218-9-3

^ ab Tyldesley, Joyce. Chronicle of the Queens of Egypt. Thames & Hudson. 2006.

ISBN 0-500-05145-3

^ Clayton, pp.57-58

^ Herodotus, Historia, B:129-132

^ Hassan, Selim: Excavations at Gîza IV. 1932–1933. Cairo: Government Press, Bulâq, 1930. pp 18-62

^ abcd Porter, Bertha and Moss, Rosalind, Topographical Bibliography of Ancient Egyptian Hieroglyphic Texts, Statues, Reliefs and Paintings Volume III: Memphis, Part I Abu Rawash to Abusir. 2nd edition (revised and augmented by Dr Jaromir Malek, 1974). Retrieved from gizapyramids.org

^ Miroslav Verner: Archaeological Remarks on the 4th and 5th Dynasty Chronology. In: Archiv Orientální, Vol. 69. Prague 2001, page 363–418.

^ Ancient Egyptian leader makes a surprise appearance at an archaeological dig in Israel July 9, 2013, sciencedaily.com

^ Guinness Book of World Records 2012. 2011. p. 194. ISBN 978-1-904994-68-8.

^ Boughton, Paul "Menkaura's Anthropoid Coffin: A Case of Mistaken Identity?" Ancient Egypt. August/September 2006. p.30-32.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Menkaura. |

Menkaure and His Queen by Dr. Christopher L.C.E. Witcombe.

View photos, videos, current status and other information on the pyramid of Menkaure at Talking Pyramids