Matthew Flinders

Matthew Flinders | |

|---|---|

Portrait by Antoine Toussaint de Chazal, painted in Mauritius in 1806-1807 | |

| Born | (1774-03-16)16 March 1774 Donington, Lincolnshire, England |

| Died | 19 July 1814(1814-07-19) (aged 40) London, England |

| Resting place | St James's burial ground, Camden (until 2019) |

| Occupation | Royal Navy Captain |

| Spouse(s) | Ann Chappelle (m. 1801) |

| Children | Anne |

Captain Matthew Flinders (16 March 1774 – 19 July 1814) was an English navigator and cartographer who led the first circumnavigation of Australia and identified it as a continent.

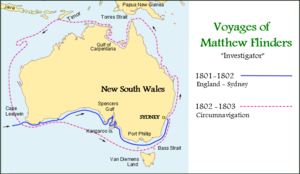

Flinders made three voyages to the southern ocean between 1791 and 1810. In the second voyage, George Bass and Flinders confirmed that Van Diemen's Land (now Tasmania) was an island. In the third voyage, Flinders circumnavigated the mainland of what was to be called Australia, accompanied by Aboriginal man Bungaree.

Heading back to England in 1803, Flinders' vessel needed urgent repairs at Isle de France (Mauritius). Although Britain and France were at war, Flinders thought the scientific nature of his work would ensure safe passage, but a suspicious governor kept him under arrest for more than six years. In captivity, he recorded details of his voyages for future publication, and put forward his rationale for naming the new continent 'Australia', as an umbrella term for New Holland and New South Wales – a suggestion taken up later by Governor Macquarie.

Flinders' health had suffered, however, and although he reached home in 1810, he did not live to see the success of his widely praised book and atlas, A Voyage to Terra Australis, having died in July 1814. The location of his grave was lost by the mid-19th century but archaeologists excavating a former burial ground near London's Euston railway station reported in January 2019 that his remains had been identified.

Contents

1 Early life

2 Command of Investigator

3 Family

4 Exploration of the Australian coastline

4.1 Observations of ocean tides

5 Attempted return to England and imprisonment

6 Death

7 Naming of Australia and discovery of Flinders' 1804 map Y46/1

8 Legacy of Flinders

9 Works

10 See also

11 Notes

12 References

13 External links

Early life

Matthew Flinders was born in Donington, Lincolnshire, England, the son of Matthew Flinders, a surgeon, and his wife Susannah, née Ward. He was educated at Cowley's Charity School, Donington, from 1780 and then at the Reverend John Shinglar's Grammar School at Horbling in Lincolnshire.[1]

In his own words, he was "induced to go to sea against the wishes of my friends from reading Robinson Crusoe",[2] and in 1790, at the age of fifteen, he joined the Royal Navy. Initially serving on HMS Alert, he transferred to HMS Scipio, and in July 1790 was made midshipman on HMS Bellerophon under Captain Pasley. By Pasley's recommendation, he joined Captain Bligh's expedition on HMS Providence, transporting breadfruit from Tahiti to Jamaica. This was also Bligh's second "Breadfruit Voyage" following on from the ill-fated voyage of the Bounty.

Flinders' first voyage to New South Wales, and first trip to Port Jackson, was in 1795 as a midshipman aboard HMS Reliance, carrying the newly appointed governor of New South Wales Captain John Hunter. On this voyage he quickly established himself as a fine navigator and cartographer, and became friends with the ship's surgeon George Bass who was three years his senior and had been born 11 miles (18 km) from Donington.

Not long after their arrival in Port Jackson, Bass and Flinders made two expeditions in two small open boats, named Tom Thumb and Tom Thumb II respectively: the first to Botany Bay and Georges River, the second, in the larger Tom Thumb II,[3] south from Port Jackson to Lake Illawarra, during which expedition they had to seek shelter at Wattamolla.

Memorial at Flinders, Victoria, commemorating the discovery of Western Port on 4 January 1798, by George Bass and the later passage of Bass Strait by Bass and Flinders in the same year

In 1798, Matthew Flinders, now a lieutenant, was given command of the sloop Norfolk with orders "to sail beyond Furneaux's Islands, and, should a strait be found, pass through it, and return by the south end of Van Diemen's Land". The passage between the Australian mainland and Tasmania enabled savings of several days on the journey from England, and was named Bass Strait, after his close friend. In honour of this discovery, the largest island in Bass Strait would later be named Flinders Island. The town of Flinders near the mouth of Western Port also commemorates Bass' discovery of that bay and port on 4 January 1798. Flinders never entered Western Port, and passed Cape Schanck only on 3 May 1802.[4]

Flinders once more sailed Norfolk, this time north on 17 July 1799; he arrived in Moreton Bay between modern-day Redcliffe and Brighton. He touched down at Pumicestone Passage, Redcliffe and Coochiemudlo Island and also rowed ashore at Clontarf. During this visit he named Redcliffe after the Red Cliffs.

In March 1800, Flinders rejoined Reliance and set sail for England.

Command of Investigator

Flinders in 1801

Flinders' work had come to the attention of many of the scientists of the day, in particular the influential Sir Joseph Banks, to whom Flinders dedicated his Observations on the Coasts of Van Diemen's Land, on Bass's Strait, etc.. Banks used his influence with Earl Spencer to convince the Admiralty of the importance of an expedition to chart the coastline of New Holland. As a result, in January 1801, Flinders was given command of HMS Investigator, a 334-ton sloop, and promoted to commander the following month.

Investigator set sail for New Holland on 18 July 1801. Attached to the expedition were the botanist Robert Brown, botanical artist Ferdinand Bauer, landscape artist William Westall, gardener Peter Good, geological assistant John Allen, and John Crosley as astronomer.[5] Vallance et al. comment that compared to the Baudin expedition this was a 'modest contingent of scientific gentlemen', which reflects 'British parsimony' in scientific endeavour.[5]

Family

On 17 April 1801, Flinders married his longtime friend Ann Chappelle (1772–1852) and had hoped to bring her with him to Port Jackson. However the Admiralty had strict rules against wives accompanying captains. Flinders brought Ann on board ship and planned to ignore the rules, but the Admiralty learned of his plans and he was severely chastised for his bad judgement and told he must remove her from the ship. This is well documented in correspondence between Flinders and his chief benefactor, Sir Joseph Banks, in May 1801:[6]

.mw-parser-output .templatequote{overflow:hidden;margin:1em 0;padding:0 40px}.mw-parser-output .templatequote .templatequotecite{line-height:1.5em;text-align:left;padding-left:1.6em;margin-top:0}

I have but time to tell you that the news of your marriage, which was published in the Lincoln paper, has reached me. The Lords of the Admiralty have heard also that Mrs. Flinders is on board the Investigator, and that you have some thought of carrying her to sea with you. This I was very sorry to hear, and if that is the case I beg to give you my advice by no means to adventure to measures so contrary to the regulations and the discipline of the Navy; for I am convinced by language I have heard, that their Lordships will, if they hear of her being in New South Wales, immediately order you to be superseded, whatever may be the consequences, and in all likelihood order Mr. Grant to finish the survey.

As a result, Ann was obliged to stay in England and would not see her husband for nine years, following his imprisonment on the Isle de France (Mauritius, at the time a French possession) on his return journey. When they finally reunited, Matthew and Ann had one daughter, Anne, (1 April 1812 - 1892), who later married William Petrie (1821–1908). In 1853, the governments of New South Wales and Victoria bequeathed a belated pension to her (deceased) mother of £100 per year, to go to surviving issue of the union. This she accepted on behalf of her young son, William Matthew Flinders Petrie, who would go on to become an accomplished archaeologist and Egyptologist.

Exploration of the Australian coastline

Flinders in Investigator

Aboard Investigator, Flinders reached and named Cape Leeuwin on 6 December 1801, and proceeded to make a survey along the southern coast of the Australian mainland.[7][8] On his way he stopped in at Oyster Harbour, Western Australia (34°59′37.9″S 117°56′39.8″E / 34.993861°S 117.944389°E / -34.993861; 117.944389). There he found a copper plate that Captain Christopher Dixson, on Elligood, had left the year before. It was inscribed, "Aug. 27 1800. Chr Dixson, ship Elligood".

On 8 April 1802, while sailing east, Flinders sighted Géographe, a French corvette commanded by the explorer Nicolas Baudin, who was on a similar expedition for his government. Both men of science, Flinders and Baudin met and exchanged details of their discoveries; Flinders named the bay Encounter Bay.

Proceeding along the coast, Flinders explored Port Phillip, which unbeknownst to him had been discovered only ten weeks earlier by John Murray aboard HMS Lady Nelson. Flinders scaled Arthur's Seat, the highest point near the shores of the southernmost parts of the bay, where the ship had entered through The Heads. From there he saw a vast view of the surrounding land and bays. Flinders reported back to Governor King that the land had "a pleasing and, in many parts, a fertile appearance".[9] After scaling the You Yangs to the northwest on 1 May, he stated "I left the ship's name on a scroll of paper, deposited in a small pile of stones upon the top of the peak". Here, Flinders was drawing upon a British tradition of constructing a stone cairn to mark a historical location.

The Matthew Flinders Cairn, which was later enlarged, is located on the upper slopes of Arthur's Seat, a short distance below Chapman's Point.[10]

With stores running low, Flinders proceeded to Sydney, arriving on 9 May 1802. Here he was rejoined by Bungaree, the Aboriginal man who had accompanied him on his earlier coastal survey in 1799.[11]

Having hastily prepared the ship, Flinders set sail again on 22 July, heading north and surveying the coast of Queensland. From there he passed through the Torres Strait, and explored the Gulf of Carpentaria. During this time, the ship was discovered to be badly leaking, and despite careening, they were unable to effect the necessary repairs. Reluctantly, Flinders returned to Sydney, though via the western coast, completing the circumnavigation of the continent. On the way, Flinders jettisoned two wrought-iron anchors which were found by divers in 1973 at Middle Island, Recherche Archipelago, Western Australia.[12] The best bower anchor is on display at the South Australian Maritime Museum while the stream anchor can be seen at the National Museum of Australia.[13][14][15]

Arriving in Sydney on 9 June 1803, Investigator was subsequently judged to be unseaworthy and condemned.

Observations of ocean tides

While not formally trained in natural philosophy (now termed physics) Flinders made the valuable observation of the dodge tide in South Australia. He also advanced the correct reason of the large diurnal tide in Queensland.[citation needed] These phenomena were finally confirmed by G. I. Taylor in his landmark 1919 Irish Sea analysis.[16]

Flinders coined the term "dodge tide" in reference to his 1802/3 observations that the tides in the very shallow Spencer and St Vincent's Gulfs seemed to be completely inert for several days, at select locations. Such phenomena have now also been found in the Gulf of Mexico and in the Irish Sea. Taylor noticed that the apparent amphidromic points in the Irish Sea to be ephemeral, contrary to Laplace's theory. He also noted that the current shears often exceeded the Reynolds stability limit.[clarification needed] Taylor and later workers determined these aperiodic phenomena to be a consequence of the Irish Sea being shallow and can be comparable to the thickness of the bottom boundary layer. In both the Irish Sea and the two South Australian gulfs, a north bound wave from the open ocean interferes non-linearly and with a reflected and weaker southbound wave, resulting in aperiodic and very dissipative tidal motions. The total dissipation of these two very large gulfs has not yet been calculated. The shallow Bering Sea dissipates some 50% of global input power. These ocean dissipative hot spots are alone capable of preventing the Gerstenkorn catastrophe[clarification needed] of seas turned to steam and highly elliptical planetary orbits, by providing a rapid and non-geological energy sink.[17]

In his 1803 observations of the large tides at Broad Sound in Queensland (up to 11m range) Flinders correctly attributed this to two waves travelling north and south, respectively, and meeting at Broad Sound. He postulated that the dense reef wall further offshore caused the deep ocean tide to bifurcate at the northern southern ends of the reef, travel into shallow shelf waters and meet at Broad Sound. The concept of two meeting waves was used by Taylor in his Irish Sea analysis.[16]

Attempted return to England and imprisonment

Play media

Play mediaDiscussion of Flinders and Nicholas Baudin's race to map Australia

Unable to find another vessel suitable to continue his exploration, Flinders set sail for England as a passenger aboard HMS Porpoise. However, the ship was wrecked on Wreck Reefs, part of the Great Barrier Reef, approximately 700 miles (1,100 km) north of Sydney. Flinders navigated the ship's cutter across open sea back to Sydney, and arranged for the rescue of the remaining marooned crew. Flinders then took command of the 29-ton schooner HMS Cumberland in order to return to England, but the poor condition of the vessel forced him to put in at French-controlled Isle de France (now known as Mauritius) for repairs on 17 December 1803, just three months after Baudin had died there.

War with France had broken out again the previous May, but Flinders hoped his French passport (despite its being issued for Investigator and not Cumberland)[18] and the scientific nature of his mission would allow him to continue on his way. Despite this, and the knowledge of Baudin's earlier encounter with Flinders, the French governor, Charles Mathieu Isidore Decaen, detained Flinders. The relationship between the men soured: Flinders was affronted at his treatment, and Decaen insulted by Flinders' refusal of an invitation to dine with him and his wife. Decaen was suspicious of the alleged scientific mission as the Cumberland carried no scientists and Decaen's search of Flinders' vessel uncovered a trunk full of papers (including despatches from the New South Wales Governor Philip Gidley King) that were not permitted under his scientific passport.[18] Furthermore, one of King's despatches was specifically to the British Admiralty requesting more troops in case Decean were to attack Port Jackson.[19] Among the papers seized were the three logs of HMS Investigator of which only Volume 1 and Volume two were returned to Flinders; these are now both held by the State Library of New South Wales. The third volume was later deposited in the Admiralty Library and is now held in the British Public Record Office.[20] Decaen referred the matter to the French government; this was delayed not only by the long voyage but also by the general confusion of war. Eventually, on 11 March 1806, Napoleon gave his approval, but Decaen still refused to allow Flinders' release. By this stage Decaen believed Flinders' knowledge of the island's defences would have encouraged Britain to attempt to capture it.[21] Nevertheless, in June 1809 the Royal Navy began a blockade of the island, and in June 1810 Flinders was paroled. Travelling via the Cape of Good Hope on Olympia, which was taking despatches back to Britain, he received a promotion to post-captain, before continuing to England.

Flinders had been confined for the first few months of his captivity, but he was later afforded greater freedom to move around the island and access his papers.[22] In November 1804 he sent the first map of the landmass he had charted (Y46/1) back to England. This was the only map made by Flinders where he used the name AUSTRALIA (all capitals) for the title, and the first known time he used the word Australia.[23] Due to the delay caused by his lengthy confinement, the first published map of the Australian continent was the Freycinet Map of 1811, a product of the Baudin expedition.

Flinders finally returned to England in October 1810. He was in poor health but immediately resumed work preparing A Voyage to Terra Australis[24] and his atlas of maps for publication. The full title of this book, which was first published in London in July 1814, was given, as was common at the time, a synoptic description: A Voyage to Terra Australis: undertaken for the purpose of completing the discovery of that vast country, and prosecuted in the years 1801, 1802, and 1803 in His Majesty's ship the Investigator, and subsequently in the armed vessel Porpoise and Cumberland Schooner. With an account of the shipwreck of the Porpoise, arrival of the Cumberland at Mauritius, and imprisonment of the commander during six years and a half in that island . Original copies of the Atlas to Flinders' Voyage to Terra Australis are held at the Mitchell Library in Sydney as a portfolio that accompanied the book and included engravings of 16 maps, four plates of views and ten plates of Australian flora.[25] The book was republished in three volumes in 1964, accompanied by a reproduction of the portfolio. Flinders' map of Terra Australia was first published in January 1814[26] and the remaining maps were published before his atlas and book.

Death

Flinders died, aged 40, on 19 July 1814, the day after the book and atlas was published. On 23 July, he was interred in the burial ground of St James's Church, Piccadilly, which was located some way from the church, beside Hampstead Road, Camden, London.[27][28] The burial ground was in use from 1790 until 1853.[29] By 1852, the location of the grave had been forgotten due to alterations to the burial ground.[30]

The cemetery became St James's Gardens, Camden, in 1878 with only a few gravestones lining the edges of the park.[31] Part of the gardens, located between Hampstead Road and Euston railway station, was built over when Euston station was expanded,[32] and Flinders' grave was thought to possibly lie under a platform at the station.[33] The Gardens were closed to the public in 2017.[34]

The grave was re-located in January 2019 by archaeologists working on the High Speed 2 rail project which requires the expansion of Euston station.[30][35] His coffin was identified by its well-preserved lead coffin plate.[30][36] It is proposed to re-bury his remains, at a site to be decided, after they have been examined by osteo-archaeologists.[30]

Naming of Australia and discovery of Flinders' 1804 map Y46/1

View of Port Jackson taken from South from A Voyage to Terra Australis

Flinders' map Y46/1 was never "lost". It had been stored and recorded by the UK Hydrographic Office before 1828. Geoffrey C. Ingleton mentioned Y46/1 in his book Matthew Flinders Navigator and Chartmaker on page 438.[37] By 1987 every library in Australia had access to a microfiche copy of Flinders Y46/1.[38] In 2001–2002 the Mitchell Library Sydney displayed Y46/1 at their "Matthew Flinders – The Ultimate Voyage" exhibition.[39] Paul Brunton called Y46/1 "the memorial of the great naval explorer Matthew Flinders". The first hard-copy of Y46/1 and its cartouche was retrieved from the UK Hydrographic Office (Taunton, Somerset) by historian Bill Fairbanks in 2004. On 2 April 2004, copies of the chart were presented by three of Matthew Flinders's descendants to the Governor of New South Wales, in London, to be presented in turn to the people of Australia through their parliaments by 14 November, the 200th anniversary of the chart leaving Mauritius. This celebration marked the first time the naming of Australia was formally recognised.[40]

Flinders was not the first to use the word "Australia", nor was he the first to apply the name specifically to the continent.[41] He owned a copy of Alexander Dalrymple's 1771 book An Historical Collection of Voyages and Discoveries in the South Pacific Ocean, and it seems likely he borrowed it from there, but he applied it specifically to the continent, not the whole South Pacific region. In 1804 he wrote to his brother: "I call the whole island Australia, or Terra Australis" and later that year he wrote to Sir Joseph Banks and mentioned "my general chart of Australia." A map Flinders constructed from all the information he had accumulated while he was in Australian waters and finished while he was detained by the French in Mauritius. Flinders explained in his letter to Banks:[42][43]

The propriety of the name Australia or Terra Australis, which I have applied to the whole body of what has generally been called New Holland, must be submitted to the approbation of the Admiralty and the learned in geography. It seems to me an inconsistent thing that captain Cooks New South Wales should be absorbed in the New Holland of the Dutch, and therefore I have reverted to the original name Terra Australis or the Great South Land, by which it was distinguished even by the Dutch during the 17th century; for it appears that it was not until some time after Tasman's second voyage that the name New Holland was first applied, and then it was long before it displaced T’Zuydt Landt in the charts, and could not extend to what was not yet known to have existence; New South Wales, therefore, ought to remain distinct from New Holland; but as it is requisite that the whole body should have one general name, since it is now known (if there is no great error in the Dutch part) that it is certainly all one land, so I judge, that one less exceptionable to all parties and on all accounts cannot be found than that now applied.

Flinders continued to promote the use of the word until his arrival in London in 1810. Here he found that Banks did not approve of the name and had not unpacked the chart he had sent him, and that "New Holland" and "Terra Australis" were still in general use. As a result, a book by Flinders was published under the title A Voyage to Terra Australis despite his objections. The final proofs were brought to him on his deathbed, but he was unconscious. The book was published on 18 July 1814, but Flinders did not regain consciousness and died the next day, never knowing that his name for the continent would be accepted.[44]

1744 Chart of Hollandia Nova – Terra Australis by Emanuel Bowen

Banks wrote in a draft introduction to Flinders' Voyage, referring to the map published by Melchisédech Thévenot in Relations des Divers Voyages (1663), and made well-known to English readers by Emanuel Bowen's adaptation of it, A Complete Map of the Southern Continent, published in John Campbell's editions of John Harris's Navigantium atque Itinerantium Bibliotheca, or Voyages and Travels (1744–48, and 1764):[45][46]

It was not until after Tasman's second voyage, in 1644, that the general name Terra Australis, or Great South Land, was made to give place to the new term of New Holland; and it was then applied only to the parts lying westward of a meridian line, passing through Arnhem's Land on the north, and near the Isles St Peter and St Francis on the south: All to the eastward, including the shores of the Gulph of Carpentaria, still remained Terra Australis. This appears from a chart by Thevenot in 1663, which he says "was originally taken from that done in inlaid work upon the pavement of the new Stadt House at Amsterdam". It is necessary, however, to geographical precision that the whole of this great body of land should be distinguished by one general term, and under the circumstances of the discovery of the different parts, the original Terra Australis has been judged the most proper. Of this term, therefore, we shall hereafter make use when speaking of New Holland and New South Wales in a collective sense; and when using it in an extensive signification, the adjacent isles, including that of Van Diemen, must be understood to be comprehended.

Although Thévenot said that he had taken his chart from the one inlaid into the floor of the Amsterdam Town Hall, in fact it appears to be an almost exact copy of that of Joan Blaeu in his Archipelagus Orientalis sive Asiaticus published in 1659.[47] It appears to have been Thévenot who introduced a differentiation between Nova Hollandia to the west and Terre Australe to the east of the meridian corresponding to 135° East of Greenwich, emphasised by the latitude staff running down that meridian, as there is no such division on Blaeu's map.[48]

In his book, Flinders wrote:[49]

There is no probability, that any other detached body of land, of nearly equal extent, will ever be found in a more southern latitude; the name Terra Australis will, therefore, remain descriptive of the geographical importance of this country, and of its situation on the globe: it has antiquity to recommend it; and, having no reference to either of the two claiming nations, appears to be less objectionable than any other which could have been selected.

...with the accompanying note at the bottom of the page:[50]

Had I permitted myself any innovation upon the original term, it would have been to convert it into Australia; as being more agreeable to the ear, and an assimilation to the names of the other great portions of the earth.

So Flinders had concluded that the Terra Australis, as hypothesised by Aristotle and Ptolemy (which would later be discovered as Antarctica) did not exist; therefore he wanted the name applied to the continent of Australia, and it stuck.

Flinders' book was widely read and gave the term "Australia" general currency. Lachlan Macquarie, Governor of New South Wales, became aware of Flinders' preference for the name Australia and used it in his dispatches to England. On 12 December 1817[44] he recommended to the Colonial Office that it be officially adopted. In 1824 the British Admiralty agreed that the continent should be known officially as Australia.

Legacy of Flinders

Australia 10 Shillings 1961–1965 ND Banknote. Obverse: Bust of Flinders. Reverse: Parliament House in Canberra

Statue of Flinders outside St Paul's Cathedral, Melbourne

Although he never used his own name for any feature in all his discoveries, Flinders' name is now associated with over 100 geographical features and places in Australia,[51] including Flinders Island in Bass Strait, but not Flinders Island in South Australia, which he named for his younger brother, Samuel Flinders.[51][52]

Flinders is seen as being particularly important in South Australia, where he is considered the main explorer of the state. Landmarks named after him in South Australia include the Flinders Ranges and Flinders Ranges National Park, Flinders Column at Mount Lofty,[53]Flinders Chase National Park on Kangaroo Island, Flinders University, Flinders Medical Centre, the suburb Flinders Park and Flinders Street in Adelaide. In Victoria, eponymous places include Flinders Peak, Flinders Street in Melbourne, the suburb of Flinders, the federal electorate of Flinders, and the Matthew Flinders Girls Secondary College in Geelong.

Flinders Bay in Western Australia and Flinders Way in Canberra also commemorate him. Educational institutions named after him include Flinders Park Primary School on South Australia, and Matthew Flinders Anglican College on the Sunshine Coast in Queensland. A former electoral district of the Queensland Parliament was named Flinders. There are also Flinders Highways in both Queensland and South Australia.

Bass and Flinders Point in Cronulla, New South Wales

Bass & Flinders Point in the southernmost part of Cronulla in New South Wales features a monument to George Bass and Matthew Flinders, who explored the Port Hacking estuary.

Australia holds a large collection of statues erected in Flinders' honour. In his native England, the first statue of Flinders was erected on 16 March 2006 (his birthday) in his hometown of Donington. The statue also depicts his beloved cat Trim, who accompanied him on his voyages. In July 2014, on the 200-year anniversary of his death, a large bronze statue of Flinders by the sculptor Mark Richards was unveiled at Australia House, London by Prince William, Duke of Cambridge, and later installed at Euston Station near the presumed location of his grave.[33]

Flinders' proposal[54] for the use of iron bars to be used to compensate for the magnetic deviations caused by iron on board a ship resulted in their being known as Flinders bars.

Flinders, who was Sir John Franklin's cousin by marriage, John's mother Hannah being the sister of Matthew's step mother Elizabeth, instilled in him a love for navigating and took him with him on his voyage aboard Investigator.

In 1964 he was honoured on a postage stamp issued by Postmaster-General's Department,[55] again in 1980,[56] and in 1998 with George Bass.[57]

Flindersia is a genus of 14 species of tree in the citrus family. Named by Investigator's botanist, Robert Brown in honour of Matthew Flinders.[58]

Flinders landed on Coochiemudlo Island on 19 July 1799, while he was searching for a river in the southern part of Moreton Bay, Queensland, Australia.[59]

The island's residents celebrate Flinders Day annually, commemorating the landing. The celebrations are usually held on a weekend near 19 July, the actual date of the landing.[60]

Works

A Voyage to Terra Australis, with an accompanying Atlas. 2 vol. – London : G & W Nicol, 18 July 1814

Australia Circumnavigated: The Journal of HMS Investigator, 1801–1803. Edited by Kenneth Morgan, 2 vols, The Hakluyt Society, London, 2015.[2]

Trim: Being the True Story of a Brave Seafaring Cat.

Private Journal 1803–1814. Edited with an introduction by Anthony J. Brown and Gillian Dooley. Friends of the State Library of South Australia, 2005.

Flinders, Matthew (1806). "Observations upon the Marine Barometer, Made during the Examination of the Coasts of New Holland and New South Wales, in the Years 1801, 1802, and 1803". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society. 96: 239–266. doi:10.1098/rstl.1806.0012..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

Flinders, Matthew (1805). "Concerning the Differences in the Magnetic Needle, on Board the Investigator, Arising from an Alteration in the Direction of the Ship's Head". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society. 95: 186–197. doi:10.1098/rstl.1805.0012.

See also

- Flinders bar

- List of explorers

- Trim (cat)

- European and American voyages of scientific exploration

- Matthew Flinders Medal and Lecture

Notes

^ Matthew Flinders - his life in Donington Archived 21 September 2017 at the Wayback Machine South Holland Life. Accessed 14 July 2017.

^ Scott, Chapter 2

^ The Journal of Daniel Paine 1794–1797 page 39

^ In the wake of Bass and Flinders: 200 years on :the story of the re-enactment voyages 200 years on... | National Library of Australia Archived 13 November 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Catalogue.nla.gov.au. Retrieved on 2 August 2013.

^ ab Vallance, T.G., Moore, D.T. & Groves, E.W. 2001. Nature's Investigator The Diary of Robert Brown in Australia, 1801-1805, Australian Biological Resources Study, Canberra, (p.7)

^ Scott, Ernest Findlay (1914). The Life of Captain Matthew Flinders. Sydney: Angus & Robertson. ISBN 978-0207197178.

^ Dany Bréelle, 'Matthew Flinders's Australian Toponymy and its British Connections', The Journal of the Hakluyt Society, November 2013 "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 April 2015. Retrieved 15 January 2015.CS1 maint: Archived copy as title (link)

^ Captain M. K. Barritt, RN, 'Matthew Flinders's Survey Practices and Records', The Journal of the Hakluyt Society, March 2014 "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 August 2014. Retrieved 15 January 2015.CS1 maint: Archived copy as title (link)

^ "AUSTRALIAN EXPLORATION MATTHEW FLINDERS IN PORT PHILLIP". The Argus. Melbourne. 24 April 1948. p. 18 Supplement: The Argus Week-End Magazine. Retrieved 7 February 2012 – via National Library of Australia.

^ "IN MEMORY OF FLINDERS". The Advertiser. Adelaide. 8 December 1914. p. 6. Retrieved 7 February 2012 – via National Library of Australia.

^ Bungaree Archived 4 September 2012 at Wikiwix Australian Dictionary of Biography. Accessed 9 November 2015.

^ Christopher, P. & Cundell, N. (editors), (2004), Let's Go For a Dive, 50 years of the Underwater Explorers Club of SA, published by Peter Christopher, Kent Town, SA, pp.45–49. This describes the search and recovery of the anchors by members of the Underwater Explorers Club of South Australia

^ Christopher, P. & Cundell, N. (editors), (2004), Let's Go For a Dive, 50 years of the Underwater Explorers Club of SA, published by Peter Christopher, Kent Town, SA, pp.48

^ "HM Sloop Investigator anchor | SA Maritime Museum". Maritime.historysa.com.au. Archived from the original on 29 October 2013. Retrieved 25 October 2013.

^ "NMA Collections Search – Stream anchor from Matthew Flinders' ship the 'Investigator'". Nma.gov.au. 14 January 1973. Archived from the original on 29 October 2013. Retrieved 25 October 2013.

^ ab Tidal Friction in the Irish Sea, G.I. Taylor, 1919, DOI:10.1098/rspa.1919.0059

^ Once Again – Tidal Friction, W. Munk, Qtly J. Ryl Astron Soc, Vol. 9, p352, 1968.

^ ab "Flinders' Voyage: Ships". State Library of South Australia. Archived from the original on 11 June 2017. Retrieved 11 June 2017.

^ Bennett, Bruce (2011). "Exploration or Espionage? Flinders and the French" (PDF). Journal of the European Association of Studies on Australia. 2 (1): 19.

^ Ida Leeson (1936). The Mitchell Library, Sydney : historical and descriptive notes. State Library of New South Wales, Sydney.

^ Brown, Anthony Jarrold (2000), Ill-starred captains : Flinders and Baudin, Crawford House Pub, p. 409, ISBN 978-1-86333-192-0,At this critical junction Decaen could not risk releasing Flinders ... he questioned why Admiral Pellew should involve himself personally in the navigator's release – unless it were to interrogate him on the military strength and defences of Isle de France. By now Flinders was a well-informed witness to the weaknesses of the latter, and how easily a small force might overcome them.

^ Dany Bréelle, 'The Scientific Crucible of Île de France: the French Contribution to the Work of Matthew Flinders', The Journal of the Hakluyt Society, June 2014 "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 April 2015. Retrieved 15 January 2015.CS1 maint: Archived copy as title (link)

^ Matthew Flinders, General Chart of Terra Australis or Australia, London, 1814 Archived 4 August 2017 at the Wayback Machine

^ A Voyage to Terra Australis Volume I. Gutenberg.org. 17 July 2004. Archived from the original on 6 November 2012. Retrieved 25 October 2013.

^ State Library of New South Wales /Catalogue. Library.sl.nsw.gov.au. Retrieved on 2 August 2013.

^ All maps published by the British H/Office are dated.

^ "Final resting place". Matthew Flinders Memorial. Retrieved 25 January 2019.

^ "St. James Church, Hampstead Road". Survey of London: volume 21: The parish of St Pancras part 3: Tottenham Court Road & Neighbourhood. 1949. pp. 123–136. Retrieved 15 December 2012.

^ "HS2 exhumations prompt memorial service". BBC News. 2017-08-23.

^ abcd Addley, Esther (24 January 2019). "Grave of Matthew Flinders discovered after 200 years near London station". The Guardian. Retrieved 24 January 2019.

^ "St. James' Gardens". London Cemeteries. 2011-07-12. Retrieved 2015-03-02.

^ "The body now lying under Platform 12 at Euston Station is . . . | London My London | One-stop base to start exploring the most exciting city in the world". London My London. 2013-08-10. Retrieved 2015-03-02.

^ ab Miranda, C.: Skeleton of renowned explorer Matthew Flinders is lying in the path of London rail link — and could be exhumed News Limited Network, 28 February 2014. Accessed 13 April 2014.

^ "St. James Gardens – A Casualty Of HS2". Retrieved 25 January 2019.

^ The announcement appeared in Australian media on 25 January, the day before Australia Day.

^ Whalan, Roscoe. "Body of explorer Matthew Flinders found under London train station during HS2 dig, ending 200-year mystery". ABC. Retrieved 24 January 2019.

^ Matthew Flinders: navigator and chartmaker / by Geoffrey C. Ingleton ; foreword by HRH the Prince P... | National Library of Australia Archived 22 March 2014 at the Wayback Machine. Catalogue.nla.gov.au. Retrieved on 2 August 2013.

^ Charts [microform] : pre-1825 :[M406], 1770–1824 | National Library of Australia Archived 22 March 2014 at the Wayback Machine. Catalogue.nla.gov.au. Retrieved on 2 August 2013.

^ Matthew Flinders : the ultimate voyage / State Library of New South Wales | National Library of Australia Archived 22 March 2014 at the Wayback Machine. Catalogue.nla.gov.au. Retrieved on 2 August 2013.

^ "The chart that put Australia on the map", The Sydney Morning Herald, 9 June 2004 Archived 27 January 2011 at the Wayback Machine

^ "First Instance of the Word Australia being applied specifically to the Continent - in 1794" Archived 10 November 2015 at Wikiwix Zoology of New Holland – Shaw, George, 1751–1813; Sowerby, James, 1757–1822 Page 2.

^ Flinders to Banks, Isle of France (Mauritius), 23 March 1804, Royal Greenwich Observatory, Herstmonceux-Board of Longitude Papers, RGO 14/51: 18 f.172

^ Flinders, Matthew. "Letter from Matthew Flinders originally enclosing a chart of 'New Holland' (Australia)". cudl.lib.cam.ac.uk. Cambridge Digital Library. Archived from the original on 20 July 2014. Retrieved 18 July 2014.

^ ab The Weekend Australian, 30 – 31 December 2000, p. 16

^ E. Bowen, sculp. "A Complete Map of the Southern Continent survey'd by Capt. Abel Tasman & depicted by order of the East India Company in Holland in the Stadt House at Amsterdam". Archived from the original on 19 October 2013. Retrieved 25 October 2013.

^ [1][dead link]

^ National Library of Australia, Maura O'Connor, Terry Birtles, Martin Woods and John Clark, Australia in Maps: Great Maps in Australia's History from the National Library's Collection, Canberra, National Library of Australia, 2007, p.32; this map is reproduced in Gunter Schilder, Australia Unveiled, Amsterdam, Theatrum Orbis Terrarum, 1976, p.402. image at: home Archived 5 May 2012 at the Wayback Machine See also Joan Blaeu, Nova et accvratissima totivs terrarvm orbis tabvla, 1667 Archived 31 July 2013 at Wikiwix

^ Margaret Cameron Ash, "French Mischief: A Foxy Map of New Holland", The Globe, no.68, 2011, pp.1–14.

^ Matthew Flinders, A voyage to Terra Australis (Introduction) Archived 11 November 2012 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 25 January 2013.

^ Matthew Flinders, A Voyage to Terra Australis, London, Nicol, 1814, Vol.I, p.iii.

^ ab The intrepid spirit of Matthew Flinders lives on in more than 100 Australian sites ABC News, 26 January 2019. Retrieved 26 January 2019.

^ Flinders, 1814 (1966), p. 223

^ Smith, Pam; Pate, F. Donald; Martin, Robert (2006). Valleys of Stone: The Archaeology and History of Adelaide's Hills Face. Belair, South Australia: Kōpi Books. p. 232. ISBN 0 975 7359-6-9.

^ Flinders (1805)

^ "Australia 10/- Stamp". Australianstamp.com. Archived from the original on 29 October 2013. Retrieved 25 October 2013.

^ "Australia 20c Stamp". Australianstamp.com. Archived from the original on 29 October 2013. Retrieved 25 October 2013.

^ "Australia 45c Stamp". Australianstamp.com. Archived from the original on 29 October 2013. Retrieved 25 October 2013.

^ Floyd, A. G., Rainforest Trees of Mainland South-eastern Australia, Inkata Press 2008,

ISBN 978-0-9589436-7-3 page 357

^ "Coochiemudlo Island". About Redlands. Redland City Council. Archived from the original on 30 April 2014. Retrieved 22 May 2014.

^ "Flinders Day on Coochie". Archived from the original on 23 May 2014. Retrieved 22 May 2014.

References

Bastian, Josephine (2016). 'A passion for exploring new countries': Matthew Flinders & George Bass. North Melbourne, Vic: Australian Scholarly Publishing. ISBN 978-1-925333-72-5.

Austin, K. A. (1964). The Voyage of the Investigator, 1801–1803, Commander Matthew Flinders, R.N. London and Sydney: Angus and Robertson.

Baker, Sidney J. (1962). My Own Destroyer : a biography of Matthew Flinders, explorer and navigator. Sydney: Currawong Publishing Company.

Cooper, H. M. (1966). "Flinders, Matthew (1774–1814)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Canberra: Australian National University. Retrieved 1 October 2008.

Estensen, Miriam (2002). Matthew Flinders: The life of Matthew Flinders. Crows Nest, NSW: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 978-1-86508-515-9.

Flinders, Matthew; Flannery, Timothy – (introduction) (2000). Terra Australis: Matthew Flinders' Great Adventures in the Circumnavigation of Australia. Text Publishing Company. ISBN 978-1-876485-50-4.

Fornasiero, Jean; Monteath, Peter; West-Sooby, John (2004). Encountering Terra Australis: the Australian voyages of Nicholas Baudin and Matthew Flinders. Kent Town, SA: Wakefield Press. ISBN 978-1-86254-625-7.

Hill, David (2012). The Great Race: the race between the English and the French to complete the map of Australia. North Sydney, NSW: Random House Australia. ISBN 978 1 74275 109 2.

- Hill, Ernestine (1941). My Love Must Wait. The Story of Matthew Flinders. Sydney and London. Angus and Robertson.

Ingleton, Geoffrey C.; Monteath, Peter; West-Sooby, John (1986). Matthew Flinders : navigator and chartmaker. Genesis Publications in association with Hedley Australia. ISBN 978-0-904351-34-7.

Mack, James D. (1966). Matthew Flinders 1774–1814. Melbourne: Nelson.

Morgan, Kenneth (2016). Matthew Flinders, Maritime Explorer of Australia. Bloomsbury Academic. doi:10.5040/9781474210805. ISBN 9781441179623.

Rawson, Geoffrey (1946). Matthew Flinders' Narrative of his Voyage in the Schooner Francis 1798, preceded and followed by notes on Flinders, Bass, the wreck of the Sidney Cove, &c. London: Golden Cockerel Press.

- Tugdual de Langlais, Marie-Etienne Peltier, Capitaine corsaire de la République, Éd. Coiffard, 2017, 240 p. (

ISBN 9782919339471).

Scott, Ernest (1914). The Life of Captain Matthew Flinders, RN. Sydney: Angus & Robertson. Retrieved 1 October 2008.

Serle, Percival (1949). "Flinders, Matthew". Dictionary of Australian Biography. Sydney: Angus and Robertson. Retrieved 1 October 2008.

http://catalogue.nla.gov.au/Record/1157394

External links

Wikisource has original text related to this article: Author:Matthew Flinders |

Wikisource has original text related to this article: The_Life_of_Captain_Matthew_Flinders,_R.N. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Matthew Flinders. |

Flinders, Matthew (1774–1814) National Library of Australia, Trove, People and Organisation record for Matthew Flinders

The Matthew Flinders Electronic Archive at the State Library of New South Wales.

The Flinders Papers and Charts by Matthew Flinders at the UK National Maritime Museum

Works by Matthew Flinders at Project Gutenberg

Works by Matthew Flinders at Project Gutenberg Australia

Works by or about Matthew Flinders at Internet Archive

- Flinders Providence Logbook

- Naming of Australia

Matthew Flinders' map of Australia High resolution image of the complete map.- Flinders' Journeys – State Library of NSW

- Biography at BBC Radio Lincolnshire

Voyages of Captain Matthew Flinders in Australia Google Earth Virtual Tour

Digitised copies of Flinders' logs at the British Atmospheric Data Centre

A Voyage to Terra Australis, Volume 1 – National Museum of Australia