Oscar Robertson

Robertson in the 1960s as a member of the Cincinnati Royals | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Personal information | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Born | (1938-11-24) November 24, 1938 Charlotte, Tennessee | |||||||||||||||||||

| Nationality | American | |||||||||||||||||||

| Listed height | 6 ft 5 in (1.96 m) | |||||||||||||||||||

| Listed weight | 205 lb (93 kg) | |||||||||||||||||||

| Career information | ||||||||||||||||||||

| High school | Crispus Attucks (Indianapolis, Indiana) | |||||||||||||||||||

| College | Cincinnati (1957–1960) | |||||||||||||||||||

| NBA draft | 1960 / Pick: Territorial | |||||||||||||||||||

| Selected by the Cincinnati Royals | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Playing career | 1960–1974 | |||||||||||||||||||

| Position | Point guard | |||||||||||||||||||

| Number | 14, 1 | |||||||||||||||||||

| Career history | ||||||||||||||||||||

1960–1970 | Cincinnati Royals | |||||||||||||||||||

1970–1974 | Milwaukee Bucks | |||||||||||||||||||

| Career highlights and awards | ||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||

| Career NBA statistics | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Points | 26,710 (25.7 ppg) | |||||||||||||||||||

| Rebounds | 7,804 (7.5 rpg) | |||||||||||||||||||

| Assists | 9,887 (9.5 apg) | |||||||||||||||||||

| Stats at Basketball-Reference.com | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Basketball Hall of Fame as player | ||||||||||||||||||||

| FIBA Hall of Fame as player | ||||||||||||||||||||

College Basketball Hall of Fame Inducted in 2006 | ||||||||||||||||||||

Medals

| ||||||||||||||||||||

Oscar Palmer Robertson (born November 24, 1938), nicknamed "The Big O", is an American retired professional basketball player who played for the Cincinnati Royals and Milwaukee Bucks.[1] The 6 ft 5 in (1.96 m), 205 lb (93 kg)[2] Robertson played point guard and was a 12-time All-Star, 11-time member of the All-NBA Team, and one-time winner of the MVP award in 14 professional seasons. In 1962, he became the first player in NBA history to average a triple-double for a season.[3] In the 1970–71 NBA season, he was a key player on the team that brought the Bucks their only NBA title. His playing career, especially during high school and college, was plagued by racism.[3]

Robertson is a two-time Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame inductee, having been inducted in 1980 for his individual career, and in 2010 as a member of the 1960 United States men's Olympic basketball team and president of the National Basketball Players Association. He also was voted one of the 50 Greatest Players in NBA History in 1996.[4] The United States Basketball Writers Association renamed their College Player of the Year Award the Oscar Robertson Trophy in his honor in 1998, and he was one of five people chosen to represent the inaugural National Collegiate Basketball Hall of Fame class in 2006.[5] He was ranked as the 36th best American athlete of the 20th century by ESPN.[6][7]

Robertson was also an integral part of Robertson v. National Basketball Ass'n of 1970.[8] The landmark NBA antitrust suit, named after the then-president of the NBA Players' Association, led to an extensive reform of the league's strict free agency and draft rules and, subsequently, to higher salaries for all players.[3]

Contents

1 Early years

2 Crispus Attucks High School

3 University of Cincinnati (1957–1960)

4 1960 Olympics

5 Professional career

5.1 Cincinnati Royals

5.2 Milwaukee Bucks and the 'Oscar Robertson suit'

5.3 Post-NBA career

6 Legacy

7 NBA career statistics

7.1 Regular season

7.2 Playoffs

7.3 Career highs

7.3.1 40 point games

7.3.2 Top assist games

7.3.3 Regular season

7.3.4 Playoffs

8 Personal life

9 See also

10 References

11 Further reading

12 External links

Early years

Robertson was born in poverty in Charlotte, Tennessee, and grew up in a segregated housing project in Indianapolis. In contrast to many other boys who preferred to play baseball, he was drawn to basketball because it was "a poor kids' game". Because his family could not afford to buy a basketball, he learned how to shoot by tossing tennis balls and rags bound with rubber bands into a peach basket behind his family's home.[3] Robertson attended Crispus Attucks High School, an all-black high school.

Crispus Attucks High School

At Crispus Attucks, Robertson was coached by Ray Crowe, whose emphasis on a fundamentally sound game had a positive effect on Robertson's style of play. As a sophomore in 1954, he starred on an Attucks team that lost in the semi-state finals (state quarterfinals) to eventual state champions Milan, whose story would later be the basis of the classic 1986 movie Hoosiers. When Robertson was a junior, Crispus Attucks dominated its opposition, going 31–1 and winning the 1955 state championship, the first for any all-black school in the nation. The following year the team finished with a perfect 31–0 record and won a second straight Indiana state title, becoming the first team in Indiana to secure a perfect season and compiling a state-record 45 straight victories. The state championships were also the first ever by an Indianapolis team in the Hoosier tourney. After their championship game wins, the team was paraded through town in a regular tradition, but they were then taken to a park outside downtown to continue their celebration, unlike other teams. Robertson stated, "[Officials] thought the blacks were going to tear the town up, and they thought the whites wouldn't like it."[9] Robertson scored 24.0 points per game in his senior season and was named Indiana "Mr. Basketball" in 1956.[3] After his graduation that year, Robertson enrolled at the University of Cincinnati.

University of Cincinnati (1957–1960)

Robertson continued to excel while at the University of Cincinnati, recording an incredible scoring average of 33.8 points per game, the third highest in college history. In each of his three years, he won the national scoring title, was named an All-American, and was chosen College Player of the Year, while setting 14 NCAA and 19 school records.[4]

Robertson's stellar play led the Bearcats to a 79–9 overall record during his three varsity seasons, including two Final Four appearances. However, a championship eluded Robertson, something that would become a repeated occurrence until late in his professional career. When Robertson left college he was the all-time leading NCAA scorer until fellow Hall of Fame player Pete Maravich topped him in 1970.[3] Robertson took Cincinnati to national prominence during his time there, but the university's greatest success in basketball took place immediately after his departure, when the team won national titles in 1961, 1962, and just missed a third title in 1963.

He continues to stand atop the Bearcats' record book. The many records he still holds include: points in one game, 62 (one of his six games of 50 points or more); career triple-doubles, 10; career rebounds per game, 15.2; and career points, 2,973.[10]

Robertson had many outstanding individual game performances, including 10 triple-doubles. His personal best might have been his line of 45 points, 23 rebounds and 10 assists vs. Indiana State in 1959.

Despite his success on the court, Robertson's college career was soured by racism. In those days, southern university programs such as those of Kentucky, Duke, and North Carolina did not recruit black athletes, and road trips to segregated cities were especially difficult, with Robertson often sleeping in college dorms instead of hotels. "I'll never forgive them", he told The Indianapolis Star years later.[3] Decades after his college days, Robertson's stellar NCAA career was rewarded by the United States Basketball Writers Association when, in 1998, they renamed the trophy awarded to the NCAA Division I Player of the Year the Oscar Robertson Trophy. This honor brought the award full circle for Robertson since he had won the first two awards ever presented.[11]

1960 Olympics

After college, Robertson and Jerry West co-captained the U.S. basketball team at the 1960 Summer Olympics. The team, described as the greatest assemblage of amateur basketball talent ever, steamrollered the competition to win the gold medal. Robertson was a starting forward along with Purdue's Terry Dischinger, but played point guard as well. He was the co-leading scorer with fellow NBA legend Jerry Lucas, as the U.S. team won its nine games by a margin of 42.4 points. Ten of the twelve college players on the American squad later played in the NBA, including Robertson as well as future Hall-of-Famers West, Lucas, and Walt Bellamy.[12]

Professional career

Cincinnati Royals

Robertson displaying his ball-handling talent with the Cincinnati Royals

Prior to the 1960–61 NBA season, Robertson made himself eligible for the 1960 NBA draft. He was drafted by the Cincinnati Royals as a territorial pick. The Royals gave Robertson a $33,000 signing bonus, a far cry from his childhood days when he was too poor to afford a basketball.[3] In his rookie season, Robertson averaged 30.5 points, 10.1 rebounds and 9.7 assists (leading the league), almost averaging a triple-double for the entire season. He was named NBA Rookie of the Year, was elected into the All-NBA First Team – which would happen in each of Robertson's first nine seasons – and made the first of 12 consecutive All-Star Game appearances.[1] In addition, he was named the 1961 NBA All-Star Game MVP following his 23-point, 14-assist, 9-rebound performance in a West victory. However, the Royals finished with a 33–46 record and stayed in the cellar of the Western Division.

In the 1961–62 season, Robertson became the first player in NBA history to average a triple-double for an entire season, with 30.8 points, 12.5 rebounds and 11.4 assists.[1] Robertson also set a then-NBA record for the most triple-doubles during the regular season with 41 triple-doubles; the record would stand for over half a century when, in 2016–17, Russell Westbrook recorded 42 and joined Robertson as the only other player to average a triple-double for an entire season. He broke the assists record by Bob Cousy, who had recorded 715 assists two seasons earlier, by logging 899. The Royals earned a playoff berth; however, they were eliminated in the first round by the Detroit Pistons.[13] In the next season, Robertson further established himself as one of the greatest players of his generation, averaging 28.3 points, 10.4 rebounds and 9.5 assists, narrowly missing out on another triple-double season.[1] The Royals advanced to the Eastern Division Finals, but succumbed in a seven-game series against a Boston Celtics team led by Bill Russell.[14]

In the 1963–64 season, the Royals achieved a 55–25 record,[15] which put them second place in the Eastern Division. Under new coach Jack McMahon, Robertson flourished, and for the first time in his career, he had a decent supporting cast: second scoring option Jack Twyman was now supplemented by Jerry Lucas and Wayne Embry, and fellow guard Adrian Smith helped Robertson in the backcourt. Robertson led the NBA in free-throw percentage, scored a career-high 31.4 points per game, and averaged 9.9 rebounds and 11.0 assists per game.[1] The averages for his first five NBA seasons are a triple-double: 30.3 points, 10.4 rebounds and 10.6 assists per game. He won the NBA MVP award and became the only player other than Bill Russell and Wilt Chamberlain to win it from 1960 to 1968.[3] Robertson also won his second All-Star Game MVP award that year after scoring 26 points, grabbing 14 rebounds, and dishing off 8 assists in an East victory. In the postseason, the Royals defeated the Philadelphia 76ers, but then were dominated by the Celtics 4 games to 1.[3]

Robertson averaged a triple-double for his first five seasons in the NBA with the Royals, recording averages of 30.3 points, 10.4 rebounds, and 10.6 assists per game. From the 1964–65 season on, things began to turn sour for the franchise. Despite Robertson's stellar play, never failing to record averages of at least 24.7 points, 6.0 rebounds and 8.1 assists in the six following seasons,[1] the Royals were eliminated in the first round from 1965 to 1967, then missed the playoffs from 1968 to 1970. In the 1969–70 season, the sixth disappointing season in a row, fan support was waning. To help attract the public, 41-year-old head coach Bob Cousy made a short comeback as a player. For seven games, the former Celtics point guard partnered with Robertson in the Royals' backcourt, but they missed the playoffs.[3]

Milwaukee Bucks and the 'Oscar Robertson suit'

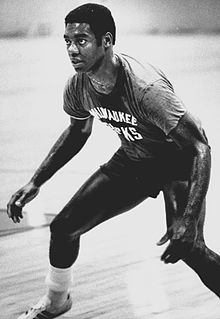

Robertson as a member of the Milwaukee Bucks

Prior to the 1970–71 season, the Royals stunned the basketball world by trading Robertson to the Bucks for Flynn Robinson and Charlie Paulk. No reasons were officially given, but many pundits suspected head coach Bob Cousy was jealous of all the attention Robertson was getting.[3] Robertson himself said: "I think he was wrong and I will never forget it."[3] The relationship between Oscar and the Royals had soured to the point that Cincinnati had also approached the Lakers and Knicks about deals involving their star player (the Knicks players who were discussed in those scenarios are unknown, but Los Angeles stated publicly that the Royals asked about Jerry West and Wilt Chamberlain, with the Lakers saying they would not consider trading either star).

However, the trade proved highly beneficial for Robertson. After being stuck with an under-performing team the last six years, he now was paired with the young Lew Alcindor, who would years later become the all-time NBA scoring leader as Kareem Abdul-Jabbar. With Alcindor in the low post and Robertson running the backcourt, the Bucks charged to a league-best 66–16 record, including a then-record 20-game win streak, a dominating 12–2 record in the playoffs, and crowned their season with the NBA title by sweeping the Baltimore Bullets 4–0 in the 1971 NBA Finals. For the first time in his career, Robertson had won an NBA championship.[3]

From a historical perspective, however, Robertson's most important contribution was made not on a basketball court, but rather in a court of law. It was the year of the landmark Robertson v. National Basketball Ass'n, an antitrust suit filed by the NBA's Players Association against the league. As Robertson was the president of the Players Association, the case bore his name. In this suit, the proposed merger between the NBA and American Basketball Association was delayed until 1976, and the college draft as well as the free agency clauses were reformed.[3] Robertson himself stated that the main reason was that clubs basically owned their players: players were forbidden to talk to other clubs once their contract was up, because free agency did not exist back then.[16] Six years after the suit was filed, the NBA finally reached a settlement, the ABA–NBA merger took place, and the Oscar Robertson suit encouraged signing of more free agents and eventually led to higher salaries for all players.[3]

On the hardwood, the veteran Robertson still proved he was a valuable player. Paired with Abdul-Jabbar, two more division titles with the Bucks followed in the 1971–72 and 1972–73 season. In Robertson's last season, he helped lead Milwaukee to a league-best 59–23 record and helped them to reach the 1974 NBA Finals. There, Robertson had the chance to end his stellar career with a second ring. The Bucks were matched up against a Boston Celtics team powered by an inspired Dave Cowens, and the Bucks lost in seven games.[3] As a testament to Robertson's importance to the Bucks, in the season following his retirement the Bucks fell to last place in their division with a 38–44 record in spite of the continued presence of Abdul-Jabbar.[17]

Robertson was elected to the Wisconsin Athletic Hall of Fame in 1995.

Post-NBA career

Robertson in 2010

After he retired as an active player, Robertson stayed involved in efforts to improve living conditions in his native Indianapolis, especially concerning fellow African-Americans.[3] In addition, he worked as a color commentator with Brent Musburger on games televised by CBS during the 1974–75 NBA season.[18] His trademark expression was "Oh, Brent, did you see that!" in reaction to flashy or spectacular situations such as fast breaks, slam dunks, player collisions, etc.

After his retirement, the Kansas City Kings (the Royals moved there while Robertson was with the Bucks) retired his #14; the retirement continues to be honored by the Kings in their current home of Sacramento. The Bucks also retired the #1 he wore in Milwaukee.

In 1994, a nine-foot bronze statue of Robertson was erected outside the Fifth Third Arena at Shoemaker Center, the current home of Cincinnati Bearcats basketball.[4] Robertson attends many of the games there, viewing the Bearcats from a chair at courtside. In 2006, the statue was relocated to the entrance of the Richard E. Lindner Athletics Center at the University of Cincinnati.[19]

Starting in 2000, Robertson served as a director for Countrywide Financial Corporation, until the company's sale to Bank of America in 2008.[20]

After many years out of the spotlight, Robertson was recognized on November 17, 2006 for his impact on college basketball when he was chosen to be a member of the founding class of the National Collegiate Basketball Hall of Fame. He was one of five people, along with John Wooden, Bill Russell, Dean Smith and Dr. James Naismith, selected to represent the inaugural class.[5]

In July 2004, Robertson was named interim head coach of the Cincinnati Bearcats men's basketball team for approximately a month while head coach Bob Huggins served a suspension stemming from a drunk-driving conviction.[21]

In January 2011, Robertson joined a class action lawsuit against the NCAA, challenging the organization's use of the images of its former student athletes.[22]

In 2015, Robertson was among a group of investors who placed a marijuana legalization initiative on the Ohio ballot.[23] The initiative sought exclusive grow rights for the group members while prohibiting all other cultivation except small amounts for personal use.[24] Robertson appeared in a television advertisement advocating for passage of the initiative,[25] but it was ultimately defeated.[26]

Legacy

Robertson is regarded as one of the greatest players in NBA history, a triple threat who could score inside, outside and also was a stellar playmaker. His rookie scoring average of 30.5 points per game is the third highest of any rookie in NBA history, and Robertson averaged more than 30 points per game in six of his first seven seasons.[1] Only three other players in the NBA have had more 30+ point per game seasons in their career. Robertson was the first player to average more than 10 assists per game, doing so at a time when the criteria for assists were more stringent than today.[3] Furthermore, Robertson is the first guard in NBA history to ever average more than 10 rebounds per game, doing so three times. It was a feat that would not be repeated until Russell Westbrook managed to achieve it during the 2016–17 season. In addition to his 1964 regular season MVP award, Robertson won three All-Star Game MVPs in his career (in 1961, 1964, and 1969). He ended his career with 26,710 points (25.7 per game, ninth-highest all time), 9,887 assists (9.5 per game) and 7,804 rebounds (7.5 per game).[1] He led the league in assists six times, and at the time of his retirement, he was the NBA's all-time leader in career assists and free throws made, and was the second all-time leading scorer behind Wilt Chamberlain.[3]

Robertson also set yardsticks in versatility. If his first five NBA seasons are strung together, Robertson averaged a triple-double over those, averaging 30.3 points, 10.4 rebounds and 10.6 assists.[27] For his career, Robertson had 181 triple-doubles, a record that has never been approached.[28] These numbers are even more astonishing if it is taken into account that the three-point shot, which benefits sharpshooting backcourt players, did not exist when he played. In 1967–68, Robertson also became the first of only two players in NBA history to lead the league in both scoring average and assists per game in the same season (also achieved by Nate Archibald). The official scoring and assist titles went to other players that season, however, because the NBA based the titles on point and assist totals (not averages) prior to the 1969–70 season. Robertson did, however, win a total of six NBA assist titles during his career. For his career, Robertson shot a high .485 field goal average and led the league in free-throw percentage twice—in the 1963–64 and 1967–68 seasons.[1]

Robertson is recognized by the NBA as the first legitimate "big guard", paving the way for other oversized backcourt players like Magic Johnson.[3] Furthermore, he is also credited with having invented the head fake and the fadeaway jump shot, a shot which Michael Jordan later became famous for.[29] For the Cincinnati Royals, now relocated and named the Sacramento Kings, he scored 22,009 points and 7,731 assists, and is all-time leader in both statistics for the combined Royals/Kings teams.[3]

Robertson at the ceremony announcing inclusion in the Old National Bank Sports Legends Avenue of Champions, at The Children's Museum of Indianapolis.

Robertson was enshrined in the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame on April 28, 1980. He received the "Player of the Century" award by the National Association of Basketball Coaches in 2000 and was ranked third on SLAM Magazine's Top 75 NBA Players in 2003, behind fellow NBA legends Michael Jordan and Wilt Chamberlain. Furthermore, in 2006, ESPN named Robertson the second greatest point guard of all time, praising him as the best post-up guard of all time and placing him only behind Los Angeles Lakers legend Magic Johnson.[27] In 2017, it was announced that a life-sized bronze sculpture of Robertson would be featured alongside other Indiana sports stars at The Children's Museum of Indianapolis' Old National Bank Sports Legends Avenue of Champions, located in the museum's sports park opening in 2018.[30]

In 1959, the Player of the Year Award was established to recognize the best college basketball player of the year by the United States Basketball Writers Association. Five nominees are presented and the individual with the most votes receives the award during the NCAA Final Four. In 1998, it was renamed the Oscar Robertson Trophy in honor of the player who won the first two awards because of his outstanding career and his continuing efforts to promote the game of basketball. In 2004, an 18" bronze statue of Robertson was sculpted by world-renowned sculptor Harry Weber.[11]

NBA career statistics

| Legend | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GP | Games played | MPG | Minutes per game | ||

| FG% | Field-goal percentage | FT% | Free-throw percentage | ||

| RPG | Rebounds per game | APG | Assists per game | ||

| PPG | Points per game | Bold | Career high | ||

| † | Denotes seasons in which Robertson won an NBA championship |

| * | Led the league |

Regular season

| Year | Team | GP | MPG | FG% | FT% | RPG | APG | PPG |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

1960–61 | Cincinnati | 71 | 42.7 | .473 | .822 | 10.1 | 9.7* | 30.5 |

1961–62 | Cincinnati | 79 | 44.3 | .478 | .803 | 12.5 | 11.4* | 30.8 |

1962–63 | Cincinnati | 80* | 44.0 | .518 | .810 | 10.4 | 9.5 | 28.3 |

1963–64 | Cincinnati | 79 | 45.1 | .483 | .853* | 9.9 | 11.0* | 31.4 |

1964–65 | Cincinnati | 75 | 45.6* | .480 | .839 | 9.0 | 11.5* | 30.4 |

1965–66 | Cincinnati | 76 | 46.0 | .475 | .842 | 7.7 | 11.1* | 31.3 |

1966–67 | Cincinnati | 79 | 43.9 | .493 | .873 | 6.2 | 10.7 | 30.5 |

1967–68 | Cincinnati | 65 | 42.5 | .500 | .873* | 6.0 | 9.7* | 29.2* |

1968–69 | Cincinnati | 79 | 43.8 | .486 | .838 | 6.4 | 9.8* | 24.7 |

1969–70 | Cincinnati | 69 | 41.5 | .511 | .809 | 6.1 | 8.1 | 25.3 |

1970–71† | Milwaukee | 81 | 39.4 | .496 | .850 | 5.7 | 8.2 | 19.4 |

1971–72 | Milwaukee | 64 | 37.3 | .472 | .836 | 5.0 | 7.7 | 17.4 |

1972–73 | Milwaukee | 73 | 37.5 | .454 | .847 | 4.9 | 7.5 | 15.5 |

1973–74 | Milwaukee | 70 | 35.4 | .438 | .835 | 4.0 | 6.4 | 12.7 |

| Career | 1040 | 42.2 | .485 | .838 | 7.5 | 9.5 | 25.7 | |

Playoffs

| Year | Team | GP | MPG | FG% | FT% | RPG | APG | PPG |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

1962 | Cincinnati | 4 | 46.3 | .519 | .795 | 11.0 | 11.0 | 28.8 |

1963 | Cincinnati | 12 | 47.5 | .470 | .864 | 13.0 | 9.0 | 31.8 |

1964 | Cincinnati | 10 | 47.1 | .455 | .858 | 8.9 | 8.4 | 29.3 |

1965 | Cincinnati | 4 | 48.8 | .427 | .923 | 4.8 | 12.0 | 28.0 |

1966 | Cincinnati | 5 | 44.8 | .408 | .897 | 7.6 | 7.8 | 31.8 |

1967 | Cincinnati | 4 | 45.8 | .516 | .892 | 4.0 | 11.3 | 24.8 |

1971† | Milwaukee | 14 | 37.1 | .486 | .754 | 5.0 | 8.9 | 18.3 |

1972 | Milwaukee | 11 | 34.5 | .407 | .833 | 5.8 | 7.5 | 13.1 |

1973 | Milwaukee | 6 | 42.7 | .500 | .912 | 4.7 | 7.5 | 21.2 |

1974 | Milwaukee | 16 | 43.1 | .450 | .846 | 3.4 | 9.3 | 14.0 |

| Career | 86 | 42.7 | .460 | .855 | 6.7 | 8.9 | 22.2 | |

Career highs

Robertson in 1966

40 point games

77 times in the regular season

Top assist games

| Assists | Opponent | Home/Away | Date |

|---|---|---|---|

22 | Syracuse Nationals | Home | October 29, 1961 |

| 22 (OT) | New York Knicks | Home | March 5, 1966 |

| 21 | New York Knicks | Home | February 14, 1964 |

| 20 | Los Angeles Lakers | Home | February 19, 1961 |

| 20 | Chicago Packers | Neutral | December 11, 1961 |

| 20 | San Francisco Warriors | Home | December 28, 1964 |

| 20 | New York Knicks | Neutral | February 28, 1965 |

| 20 | Phoenix Suns | Away | March 4, 1969 |

| 19 | St. Louis Hawks | Home | December 8, 1961 |

| 19 | Philadelphia Warriors | Home | January 11, 1962 |

| 19 | Chicago Zephyrs | Neutral | December 13, 1962 |

| 19 | San Francisco Warriors | Home | January 4, 1963 |

| 19 | Baltimore Bullets | Home | January 5, 1964 |

| 19 | Detroit Pistons | Neutral | December 1, 1964 |

| 19 | Baltimore Bullets | Home | March 18, 1965 |

| 19 | Los Angeles Lakers | Away | December 14, 1966 |

| 19 | Philadelphia 76ers | Home | December 6, 1967 |

| 19 | San Diego Rockets | Neutral | January 18, 1968 |

Regular season

| Stat | High | Opponent | Date |

|---|---|---|---|

| Points | 56 | vs. Los Angeles Lakers | December 18, 1964 |

| Field goals made | |||

| Field goal attempts | |||

| Free throws made, no misses | 18-18 | at St. Louis Hawks | January 30, 1962 |

| Free throws made, one miss | 22-23 | vs. Los Angeles Lakers | December 18, 1964 |

| Free throws made, one miss | 22-23 | vs. Baltimore Bullets | November 20, 1966 |

| Free throws made | 22 | vs. Los Angeles Lakers | December 18, 1964 |

| Free throws made | 22 | at Baltimore Bullets | December 27, 1964 |

| Free throws made | 22 | vs. Baltimore Bullets | November 20, 1966 |

| Free throw attempts | 26 | at Baltimore Bullets | December 27, 1964 |

| Rebounds | |||

| Minutes played |

Playoffs

| Stat | High | Opponent | Date |

|---|---|---|---|

| Points | 43 | at Boston Celtics | April 10, 1963 |

| Field goals made | 17 | at Boston Celtics | March 28, 1963 |

| Free throws made, 1 miss | 21-22 | at Boston Celtics | April 10, 1963 |

| Free throws made | 21 | at Boston Celtics | April 10, 1963 |

| Free throw attempts | 22 | at Boston Celtics | April 10, 1963 |

| Assists | 18 | at Philadelphia 76ers | March 29, 1964 |

| Minutes played | 58 (2OT) | at Boston Celtics | May 10, 1974 |

Personal life

Robertson is the son of Mazell and Bailey Robertson. He has two brothers, Bailey Jr. and Henry. He remembers a tough childhood, plagued by poverty and racism.[31] When a biography was going to be written about him in the 1990s, Robertson joked that his life had been "dull", and that he had been "married to the same woman for a long time".[29] In 1997, Robertson donated one of his kidneys to his daughter Tia, who suffered lupus-related kidney failure.[29] He has been an honorary spokesman for the National Kidney Foundation ever since. In 2003, he published his own autobiography, The Big O: My Life, My Times, My Game. Robertson also owns the chemical company Orchem, based in Cincinnati, Ohio.[32]

Regarding basketball, Robertson has stated that legendary Harlem Globetrotters players Marques Haynes and "clown prince" Goose Tatum were his idols.[16] Now in his seventies, he is long retired from playing basketball, although he still follows it on TV and attends most home games for the University of Cincinnati, his alma mater. He now lists woodworking as his prime hobby.[16] Robertson adds that he still could average a triple-double season in today's basketball, and that he is highly skeptical that anyone else could do it (it was later done by Russell Westbrook in the 2016–17 season). On June 9, 2007, Oscar received an Honorary Doctorate of Humane Letters from the University of Cincinnati for both his philanthropic and entrepreneurial efforts.[33]

In August 2018, Robertson auctioned off his 1971 championship ring, Hall of Fame ring, and one of his Milwaukee Bucks game jerseys. Each item sold between $50,000 and $91,000.[34]

See also

- List of National Basketball Association franchise career scoring leaders

- List of National Basketball Association career scoring leaders

- List of National Basketball Association career assists leaders

- List of National Basketball Association career free throw scoring leaders

- List of National Basketball Association career minutes played leaders

- List of National Basketball Association career playoff assists leaders

- List of National Basketball Association players with most assists in a game

- List of National Basketball Association annual minutes leaders

- List of NCAA Division I men's basketball players with 60 or more points in a game

- List of NCAA Division I men's basketball players with 2000 points and 1000 rebounds

- List of NCAA Division I men's basketball season scoring leaders

- List of NCAA Division I men's basketball career free throw scoring leaders

References

^ abcdefghi "Oscar Robertson stats". Basketball-reference.com. Retrieved 2007-01-25..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ basketball-reference.com, [1], accessed January 25, 2017.

^ abcdefghijklmnopqrstuv "Oscar Robertson nba.com summary". Nba.com. Retrieved 2007-01-25.

^ abc "Oscar Robertson Basketball Hall of Fame summary". Hoophall.com. Archived from the original on 2007-01-21. Retrieved 2007-01-25.

^ ab "Wooden, Russell lead founding class into Collegiate Hall of Fame". Abc.com. Retrieved 2007-01-25.

^ "Top N. American athletes of the century". Espn.go.com. Retrieved 2015-05-08.

^ "The Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame – Hall of Famers". Hoophall.com. Archived from the original on 2011-02-15. Retrieved 2015-05-08.

^ "Oscar defined the triple-double". Espn.go.com. Retrieved 2015-05-08.

^ Patrick Dorsey, Attucks' win helped race relations, ESPN.com, February 27, 2009

^ "2010-11 Men's basketball Media Supplement" (PDF). Grfx.cstv.com. Retrieved 2015-05-08.

^ ab "Oscar Robertson Trophy". Usbwa.com. Archived from the original on 2007-02-13. Retrieved 2007-01-25.

^ "Games of the XVIIth Olympiad -- 1960". Usabasketball.com. Archived from the original on 2006-12-31. Retrieved 2007-01-31.

^ "1962 Cincinnati Royals". Basketball-reference.com. Retrieved 2007-01-31.

^ "1963 Cincinnati Royals". Basketball-reference.com. Retrieved 2007-01-31.

^ "1964 Cincinnati Royals". Basketball-reference.com. Retrieved 2007-01-31.

^ abc "Oscar Robertson FAQ". Archived from the original on 2007-04-30. Retrieved 2007-01-31.

^ "1975 Milwaukee Bucks". Basketball-reference.com. Retrieved 2007-01-31.

[dead link]

^ "Oscar Robertson Company Information". Archived from the original on 2007-05-01. Retrieved 2007-01-31.

^ Harris, Gregory. "Varsity Village Hits a Home Run On University Campus". LandscapeOnline.com. Archived from the original on 2012-04-25. Retrieved 2011-11-26.

^ "Definitive Notice & Proxy Statement". Sec.gov. Retrieved 2015-05-08.

^ "Hall of Famer will serve until Huggins returns". Sports.espn.go.com. Retrieved 2015-05-08.

^ Wetzel, Dan (January 26, 2011). "Robertson joins suit vs. NCAA". Yahoo! Sports. Archived from the original on March 3, 2016.

^ "'The Big O' backs pot legalization". ESPN. Associated Press. January 31, 2015. Retrieved May 26, 2016.

^ Borchardt, Jackie (September 21, 2015). "What you need to know about Issue 3 -- Ohio's marijuana legalization measure". Northeast Ohio Media Group. Retrieved May 26, 2016.

^ Saker, Anne (October 27, 2015). "Deters, Big O star in pro-Issue 3 ads". The Cincinnati Enquirer. Retrieved May 26, 2016.

^ Borchardt, Jackie (November 3, 2015). "Ohio marijuana legalization measure fails". cleveland.com. Retrieved May 26, 2016.

^ ab "Daily Dime: Special Edition – The 10 Greatest Point Guards Ever". Retrieved 2007-01-25.

^ Wojnarowski, Adrian. "Making triple trouble". Retrieved 2007-01-31.

^ abc Flatter, Ron. "ESPN Classic – Oscar defined the triple-double". Retrieved 2007-01-31.

^ "Children's Museum unveils 'sports legends' for new outdoor exhibit". Indiana Business Journal. 2017-09-12.

^ [2] Archived May 31, 2006, at the Wayback Machine.

^ "Orchem Corporation". Orchemcorp.com. Retrieved 2008-07-20.

^ "UC Legend Oscar Robertson to be Honored at Spring Commencement". Uc.edu. 2007-10-04. Retrieved 2015-05-08.

^ http://www.espn.com/nba/story/_/id/24411321/oscar-robertson-1971-nba-title-ring-sells-91000

Further reading

- Robertson, Oscar The Art of Basketball: A Guide to Self-Improvement in the Fundamentals of the Game (1998)

ISBN 978-0-9662483-0-2

- Robertson, Oscar The Big O: My Life, My Times, My Game (2003)

ISBN 1-57954-764-8 autobiography - Bradsher, Bethany, Oscar Robertson Goes to Dixie (2011)

ISBN 978-0-9836825-3-0, Houston, Texas: Whitecaps Media (e-book) - Bradsher, Bethany, The Classic: How Everett Case and His Tournament Brought Big-Time Basketball to the South (2011)

ISBN 978-0-9836825-2-3, Houston, Texas: Whitecaps Media - Grace, Kevin. Cincinnati Hoops. Chicago, Illinois: Arcadia, 2003.

- Grace, Kevin; Hand, Greg; Hathaway, Tom; and Hoffman, Carey. Bearcats! The Story of Basketball at the University of Cincinnati. Louisville, Kentucky: Harmony House, 1998.

- Robertson, Oscar, Damian Aromando. Parquet Cronicles (2000)

- Roberts, Randy. But They Can't Beat Us: Oscar Robertson and the Crispus Attucks Tigers.

ISBN 1-57167-257-5

External links

- Official website

- Career statistics and player information from Basketball-Reference.com

- NBA bio

- Basketball Hall of Fame bio

- Indiana Basketball Hall of Fame profile

| Preceded by Rick Barry and Rod Hundley | NBA Finals television color commentator 1975 | Succeeded by Rick Barry and Mendy Rudolph |