Vietnam

Coordinates: 16°10′N 107°50′E / 16.167°N 107.833°E / 16.167; 107.833

Socialist Republic of Viet Nam Cộng hòa xã hội chủ nghĩa Việt Nam (Vietnamese) | |

|---|---|

Flag  Emblem | |

Motto: Độc lập – Tự do – Hạnh phúc "Independence – Freedom – Happiness" | |

Anthem: Tiến Quân Ca[n 1] (English: "Army March") | |

![Location of Vietnam (green) in ASEAN (dark grey) – [Legend]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Location_Vietnam_ASEAN.svg/250px-Location_Vietnam_ASEAN.svg.png) Location of Vietnam (green) in ASEAN (dark grey) – [Legend] | |

| Capital | Hanoi 21°2′N 105°51′E / 21.033°N 105.850°E / 21.033; 105.850 |

| Largest city | Ho Chi Minh City |

| Official language .mw-parser-output .nobold{font-weight:normal} and national language | Vietnamese |

Ethnic groups |

|

| Religion |

|

| Demonym(s) | Vietnamese |

| Government | Unitary Marxist-Leninist one-party socialist republic |

• Party General Secretary | Nguyễn Phú Trọng |

• President | Nguyễn Phú Trọng |

• Vice President | Đặng Thị Ngọc Thịnh |

• Prime Minister | Nguyễn Xuân Phúc |

• Chairwoman of National Assembly | Nguyễn Thị Kim Ngân |

| Legislature | National Assembly |

| Independence from France | |

• Declaration | 2 September 1945 |

• Geneva Accords | 21 July 1954 |

• Reunification | 2 July 1976[3] |

• Current constitution | 28 November 2013[n 3] |

| Area | |

• Total | 331,212[n 4] km2 (127,882 sq mi) (65th) |

• Water (%) | 6.38[n 4] |

| Population | |

• 2016 estimate | 94,569,072[5] (14th) |

• Density | 276.03/km2 (714.9/sq mi) (46th) |

GDP (PPP) | 2018 estimate |

• Total | $705.774 billion[6] (35th) |

• Per capita | $7,463[6] (128th) |

GDP (nominal) | 2018 estimate |

• Total | $240.779 billion[6] (47th) |

• Per capita | $2,546[6] (129th) |

Gini (2014) | 37.6[7] medium |

HDI (2017) | medium · 116th |

| Currency | đồng (₫) (VND) |

| Time zone | UTC+7 (Indochina Standard Time) |

| Date format | dd/mm/yyyy |

| Driving side | right |

| Calling code | +84 |

| ISO 3166 code | VN |

| Internet TLD | .vn |

Vietnam (UK: /ˌvjɛtˈnæm, -ˈnɑːm/, US: /ˌviːət-/ (![]() listen);[9]Vietnamese: Việt Nam pronounced [vîət nāːm] (

listen);[9]Vietnamese: Việt Nam pronounced [vîət nāːm] (![]() listen)), officially the Socialist Republic of Viet Nam (Vietnamese: Cộng hòa xã hội chủ nghĩa Việt Nam), is the easternmost country on the Indochina Peninsula. With an estimated 94.6 million inhabitants as of 2016[update], it is the world's 15th-most-populous country, and the ninth-most-populous Asian country. Vietnam is bordered by China to the north, Laos to the northwest, Cambodia to the southwest, Thailand across the Gulf of Thailand to the southwest, and the Philippines, Malaysia and Indonesia across the South China Sea to the east and southeast.[n 5] Its capital city has been Hanoi since the reunification of North and South Vietnam in 1976, with Ho Chi Minh City as the most populous city.

listen)), officially the Socialist Republic of Viet Nam (Vietnamese: Cộng hòa xã hội chủ nghĩa Việt Nam), is the easternmost country on the Indochina Peninsula. With an estimated 94.6 million inhabitants as of 2016[update], it is the world's 15th-most-populous country, and the ninth-most-populous Asian country. Vietnam is bordered by China to the north, Laos to the northwest, Cambodia to the southwest, Thailand across the Gulf of Thailand to the southwest, and the Philippines, Malaysia and Indonesia across the South China Sea to the east and southeast.[n 5] Its capital city has been Hanoi since the reunification of North and South Vietnam in 1976, with Ho Chi Minh City as the most populous city.

The northern part of Vietnam was part of Imperial China for over a millennium, from 111 BC to AD 939. An independent Vietnamese state was formed in 939, following a Vietnamese victory in the battle of Bạch Đằng River. Successive Vietnamese imperial dynasties flourished as the nation expanded geographically and politically into Southeast Asia, until the Indochina Peninsula was colonised by the French in the mid-19th century. Following a Japanese occupation in the 1940s, the Vietnamese fought French rule in the First Indochina War. On 2 September 1945, President Hồ Chí Minh declared Vietnam's independence from France under the new name of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam. In 1954, the Vietnamese declared victory in the battle of Điện Biên Phủ which took place between March and May 1954 and culminated in a major French defeat. Thereafter, Vietnam was divided politically into two rival states, North Vietnam (officially the Democratic Republic of Vietnam) and South Vietnam (officially the Republic of Vietnam). Conflict between the two sides intensified in what is known as the Vietnam War with heavy intervention by the United States on the side of South Vietnam from 1965 to 1973. The war ended with a North Vietnamese victory in 1975.

Vietnam was then unified under a communist government but remained impoverished and politically isolated. In 1986, the Communist Party of Vietnam (CPV) initiated a series of economic and political reforms that began Vietnam's path toward integration into the world economy.[11] By 2010, it had established diplomatic relations with 178 countries. Since 2000, Vietnam's economic growth rate has been among the highest in the world,[11] and in 2011, it had the highest Global Growth Generators Index among 11 major economies.[12] Its successful economic reforms resulted in its joining the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2007. Vietnam is a member of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) and the Organisation Internationale de la Francophonie (OIF).

Contents

1 Etymology

2 History

2.1 Prehistory

2.2 Dynastic Vietnam

2.3 French Indochina

2.4 First Indochina War

2.5 Vietnam War

2.6 Reunification and reforms

3 Geography

3.1 Climate

3.2 Biodiversity

3.3 Environment

4 Government and politics

4.1 Foreign relations

4.2 Military

4.3 Administrative divisions

5 Economy

5.1 Science and technology

6 Infrastructure

6.1 Transport

6.2 Energy

6.3 Health

6.4 Education

7 Demographics

7.1 Languages

7.2 Religion

8 Culture

8.1 Literature

8.2 Music

8.3 Cuisine

8.4 Media

8.5 Holidays and festivals

8.6 Sports

9 See also

10 Footnotes

11 Notes and references

11.1 Notes

11.2 References

11.2.1 Print

11.2.2 Legislation, case law and government source

11.2.3 Academic publications

11.2.4 News and magazines

11.2.5 Websites

11.2.6 Free content

12 External links

Etymology

The name Việt Nam (Vietnamese pronunciation: [viə̀t naːm]) is a variation of Nam Việt (Chinese: 南越; pinyin: Nányuè; literally "Southern Việt"), a name that can be traced back to the Triệu dynasty of the 2nd century BC.[13] The word Việt originated as a shortened form of Bách Việt (Chinese: 百越; pinyin: Bǎiyuè), a group of people then living in southern China and Vietnam.[14] The form "Vietnam" (.mw-parser-output .vi-nom{font-family:"Han-Nom Gothic","Nom Na Tong","Han-Nom Ming","Han-Nom Minh","HAN NOM A","HAN NOM B","Han-Nom Kai","Sun-ExtA","Sun-ExtB","Ming-Lt-HKSCS-UNI-H","Ming-Lt-HKSCS-ExtB","HanaMinA","HanaMinB","HanaMin","MingLiU","MingLiU-ExtB","MingLiU HKSCS","MingLiU HKSCS-ExtB","SimSun","SimSun-ExtB","FZKaiT-Extended","FZKaiT-Extended(SIP)",sans-serif}.mw-parser-output .vi-nom .ext{font-family:"Han-Nom Gothic","Han-Nom Ming","Han-Nom Minh","BabelStone Han","Sun-ExtB","MingLiU HKSCS-ExtB","Ming-Lt-HKSCS-ExtB","HanaMinB","Han-Nom Kai",sans-serif}越南) is first recorded in the 16th-century oracular poem Sấm Trạng Trình. The name has also been found on 12 steles carved in the 16th and 17th centuries, including one at Bao Lam Pagoda in Hải Phòng that dates to 1558.[15] In 1802, Nguyễn Phúc Ánh (later become Emperor Gia Long) established the Nguyễn dynasty, and in the second year, he asked the Jiaqing Emperor of the Qing dynasty to confer him the title 'King of Nam Viet/Nanyue' (南越 in Chinese) after seizing Annam's ruling power but the latter refused since the name was related to Zhao Tuo's Nanyue which includes the regions of Guangxi and Guangdong in southern China by which the Qing Emperor decide to call the area as "Viet Nam" instead.[n 6][17] Between 1804 and 1813, the name Vietnam was used officially by Emperor Gia Long.[n 6] It was revived in the early 20th century by Phan Bội Châu's History of the Loss of Vietnam, and later by the Vietnamese Nationalist Party (VNQDĐ).[18] The country was usually called Annam until 1945, when both the imperial government in Huế and the Việt Minh government in Hanoi adopted Việt Nam.[19]

History

Prehistory

A Đông Sơn bronze drum, c. 800 BC.

Archaeological excavations have revealed the existence of humans in what is now Vietnam as early as the Paleolithic age. Homo erectus fossils dating to around 500,000 BC have been found in caves in Lạng Sơn and Nghệ An provinces in northern Vietnam.[20] The oldest Homo sapiens fossils from mainland Southeast Asia are of Middle Pleistocene provenance, and include isolated tooth fragments from Tham Om and Hang Hum.[21][22][23] Teeth attributed to Homo sapiens from the Late Pleistocene have also been found at Dong Can,[24] and from the Early Holocene at Mai Da Dieu,[25][26] Lang Gao[27][28] and Lang Cuom.[29] By about 1,000 BC, the development of wet-rice cultivation and bronze casting in the Ma River and Red River floodplains led to the flourishing of the Đông Sơn culture,[30][31] notable for its elaborate bronze Đông Sơn drums.[32][33][34] At this time, the early Vietnamese kingdoms of Văn Lang and Âu Lạc appeared, and the culture's influence spread to other parts of Southeast Asia, including Maritime Southeast Asia, throughout the first millennium BC.[33][35]

Dynastic Vietnam

Map of Vietnam showing the conquest of the south (the Nam tiến), 1009–1834

Lý dynasty (1009–1225)

1069

1306 concessions

1407

1500

1578–1611

1700

1802

After Siamese–Vietnamese War (1834)

Tribal territories by 1834

Main gate of the Imperial City of Huế, the administration centre of the Nguyễn dynasty that unified Vietnam.

Trưng Sisters Parade in southern Vietnam, 1957. Both sisters are highly upheld and respected by local and overseas Vietnamese as one of the pioneers for early independence movements that freed Vietnam from Chinese dynastical domination which also celebrated until present as part of the annual Women's Day.[36][37][38]

The Hồng Bàng dynasty of the Hùng kings is considered the first Vietnamese state, known in Vietnamese as Văn Lang.[39][40] In 257 BC, the last Hùng king was defeated by Thục Phán, who consolidated the Lạc Việt and Âu Việt tribes to form the Âu Lạc, proclaiming himself An Dương Vương.[41] In 179 BC, a Chinese general named Zhao Tuo defeated An Dương Vương and consolidated Âu Lạc into Nanyue.[31] However, Nanyue was itself incorporated into the empire of the Chinese Han dynasty in 111 BC after the Han–Nanyue War.[17][42] For the next thousand years, what is now northern Vietnam remained mostly under Chinese rule.[43][44] Early independence movements, such as those of the Trưng Sisters and Lady Triệu,[45] were only temporarily successful,[46] though the region gained a longer period of independence as Vạn Xuân under the Anterior Lý dynasty between AD 544 and 602.[47][48][49] By the early 10th century, Vietnam had gained autonomy, but not sovereignty, under the Khúc family.[50]

In AD 938, the Vietnamese lord Ngô Quyền defeated the forces of the Chinese Southern Han state at Bạch Đằng River and achieved full independence for Vietnam after a millennium of Chinese domination.[51][52][53] Renamed as Đại Việt (Great Viet), the nation enjoyed a golden era under the Lý and Trần dynasties. During the rule of the Trần Dynasty, Đại Việt repelled three Mongol invasions.[54][55] Meanwhile, Buddhism of Mahāyāna tradition flourished and became the state religion.[53][56] Following the 1406–7 Ming–Hồ War which overthrew the Hồ dynasty, Vietnamese independence was briefly interrupted by the Chinese Ming dynasty, but was restored by Lê Lợi, the founder of the Lê dynasty.[57] The Vietnamese dynasties reached their zenith in the Lê dynasty of the 15th century, especially during the reign of Emperor Lê Thánh Tông (1460–1497).[58][59] Between the 11th and 18th centuries, Vietnam expanded southward in a process known as nam tiến ("southward expansion"),[60] eventually conquering the kingdom of Champa and part of the Khmer Empire.[61][62][63]

From the 16th century onward, civil strife and frequent political infighting engulfed much of Vietnam. First, the Chinese-supported Mạc dynasty challenged the Lê dynasty's power.[64] After the Mạc dynasty was defeated, the Lê dynasty was nominally reinstalled, but actual power was divided between the northern Trịnh lords and the southern Nguyễn lords, who engaged in a civil war for more than four decades before a truce was called in the 1670s.[65] During this time, the Nguyễn expanded southern Vietnam into the Mekong Delta, annexing the Central Highlands and the Khmer lands in the Mekong Delta.[61][63][66] The division of the country ended a century later when the Tây Sơn brothers established a new dynasty. However, their rule did not last long, and they were defeated by the remnants of the Nguyễn lords, led by Nguyễn Ánh and aided by the French.[67] Nguyễn Ánh unified Vietnam, and established the Nguyễn dynasty, ruling under the name Gia Long.[66]

French Indochina

French capture of Saigon as part of the Cochinchina Campaign, 1859.

French Indochina in 1913

Between 1615–1753, French traders have engaged in trade in the area around Đàng Trong and actively spreading Catholic missionaries.[68][69] Following the detention of several missionaries as the Vietnamese kingdom feel threatened with the continuous Christianisation activities,[70] the French Navy received approval from their government to intervene in Vietnam in 1834 with the aim to freed imprisoned Catholic missionaries from a kingdom that was perceived as xenophobic against foreign influence.[71] Vietnam's kingdom independence was then gradually eroded by France that was aided by large Catholic militias in a series of military conquests between 1859 and 1885.[72] In 1862, the southern third of the country became the French colony of Cochinchina.[73] By 1884, the entire country had come under French rule, with the central and northern parts of Vietnam separated in the two protectorates of Annam and Tonkin. The three Vietnamese entities were formally integrated into the union of French Indochina in 1887.[74][75] The French administration imposed significant political and cultural changes on Vietnamese society.[76] A Western-style system of modern education was developed and Catholicism was propagated widely.[77] Most French settlers in Indochina were concentrated in Cochinchina, particularly in the region of Saigon and in Hanoi, the capital of the colony.[78]

Grand Palais built for the 1902–1903 world's fair as Hanoi became French Indochina's capital.

Guerrillas of the royalist Cần Vương movement massacres around a third of Vietnam's Christian population during the colonial period as part of their rebellion against the French rule,[79][80] but was defeated in the 1890s after a decade of resistance by the Catholics as a reprisal of their earlier massacres.[81][82] Another large-scale rebellion, the Thái Nguyên uprising was also suppressed heavily.[83] Despite the French developing a plantation economy to promote the export of tobacco, indigo, tea and coffee, they largely ignored the increasing demands for civil rights and self-government. A nationalist political movement soon emerged, with leaders such as Phan Bội Châu, Phan Châu Trinh, Phan Đình Phùng, Emperor Hàm Nghi, and Hồ Chí Minh fighting or calling for independence.[84] This resulted the 1930 Yên Bái mutiny by the Vietnamese Nationalist Party (VNQDĐ) but still managed to be suppressed heavily by the French although the mutiny have caused irreparable split that causing many leading members of the organisation become a communist converts.[85][86][87] The French maintained full control over their colonies until World War II, when the war in the Pacific led to the Japanese invasion of French Indochina in 1940. Afterwards, the Japanese Empire was allowed to station its troops in Vietnam while permitting the pro-Vichy French colonial administration to continue.[88][89] Japan exploited Vietnam's natural resources to support its military campaigns, culminating in a full-scale takeover of the country in March 1945 and the Vietnamese Famine of 1945, which caused up to two million deaths.[90][91]

First Indochina War

Situation of the First Indochina War at the end of 1954.

Areas under Việt Minh control

Areas under French control

Việt Minh guerrilla encampment / fighting

In 1941, the Việt Minh which is a nationalist liberation movement based on a Communist ideology emerged under the Vietnamese revolutionary leader Hồ Chí Minh who sought independence for Vietnam from France and the end of the Japanese occupation.[92][93] Following the military defeat of Japan and the fall of its puppet Empire of Vietnam in August 1945, anarchy, rioting and murder were widespread since Saigon's administrative services collapsed.[94] The Việt Minh occupied Hanoi and proclaimed a provisional government, which asserted national independence on 2 September.[93] Earlier in July, the Allies decide to divide Indochina into half at the 16th parallel to allow Chiang Kai-shek of the Republic of China receive Japanese surrender in the north while Lord Louis Mountbatten of the British receive the surrender in the south with the Allies agreed that Indochina belonged to France.[95][96]

Partition of French Indochina after the 1954 Geneva Conference

However, as the French were weakened as a result of German occupation, the British-Indian forces together with the remaining Japanese Southern Expeditionary Army Group were used to maintain order and to help France re-establish control through the 1945–1946 War in Vietnam.[97] Hồ Chí Minh at the time chose a moderate stance to avoid military conflict with France by which he asked the French to withdraw their colonial administrators, and asked for aid from French professors and engineers to help build a modern independent Vietnam.[93] These requests, including the idea for independence, however could not be accepted by the Provisional Government of the French Republic, which dispatched the French Far East Expeditionary Corps instead to restore colonial rule, causing the Việt Minh to launch a guerrilla campaign against the French in late 1946.[92][93][98] Matters also turned worse when the Republic of China gradually fell to the communists in the Chinese Communist Revolution. The resulting First Indochina War lasted until July 1954. The defeat of French and Vietnamese loyalists in the 1954 battle of Điện Biên Phủ allowed Hồ Chí Minh to negotiate a ceasefire from a favourable position at the subsequent Geneva Conference.[93][99]

The colonial administration was ended and French Indochina was dissolved under the Geneva Accords of 1954 into three countries: Vietnam and the kingdoms of Cambodia and Laos. Vietnam was further divided into North and South administrative regions at the Demilitarised Zone, approximately along the 17th parallel north, pending elections scheduled for July 1956.[n 7] A 300-day period of free movement was permitted, during which almost a million northerners, mainly Catholics, moved south, fearing persecution by the communists.[104][105] The partition of Vietnam was not intended to be permanent by the Geneva Accords, which stipulated that Vietnam would be reunited after elections in 1956.[106] However, in 1955, the State of Vietnam's Prime Minister, Ngô Đình Diệm toppled Bảo Đại in a fraudulent referendum organised by his brother Ngô Đình Nhu, and proclaimed himself president of the Republic of Vietnam.[106] At that point the internationally recognised State of Vietnam effectively ceased to exist and was replaced by the Republic of Vietnam in the south and Hồ Chí Minh's Democratic Republic of Vietnam in the north.[106]

Vietnam War

South Vietnamese flag flying over the ruins of Đông Ba Gate through the battle of Huế, 1968.

Between 1953 and 1956, the North Vietnamese government instituted various agrarian reforms, including "rent reduction" and "land reform", which resulted in significant political oppression.[107] During the land reform, testimony from North Vietnamese witnesses suggested a ratio of one execution for every 160 village residents, which extrapolated nationwide would indicate nearly 100,000 executions.[108] Because the campaign was concentrated mainly in the Red River Delta area, a lower estimate of 50,000 executions became widely accepted by scholars at the time.[108][109] However, declassified documents from the Vietnamese and Hungarian archives indicate that the number of executions was much lower than reported at the time, although likely greater than 13,500.[110] In the South, Diệm countered North Vietnamese subversion (including the assassination of over 450 South Vietnamese officials in 1956) by detaining tens of thousands of suspected communists in "political re-education centres".[111][112] This was a ruthless program that incarcerated many non-communists, although it was also successful at curtailing communist activity in the country, if only for a time.[113] The North Vietnamese government claimed that 2,148 individuals were killed in the process by November 1957.[114] The pro-Hanoi Việt Cộng began a guerrilla campaign in the late 1950s to overthrow Diệm's government.[115] From 1960, the Soviet Union and North Vietnam signed treaties providing for further Soviet military support.[116][117][118]

Three US Fairchild UC-123B aircraft spraying Agent Orange during the Operation Ranch Hand as part of the overall herbicidal warfare operation called Trail Dust with the aim to deprive the food and vegetation cover of the Việt Cộng, c. 1962–1971.

In 1963, Buddhist discontent with Diệm's regime erupted into mass demonstrations, leading to a violent government crackdown.[119] This led to the collapse of Diệm's relationship with the United States, and ultimately to the 1963 coup in which Diệm and Nhu were assassinated.[120] The Diệm era was followed by more than a dozen successive military governments, before the pairing of Air Marshal Nguyễn Cao Kỳ and General Nguyễn Văn Thiệu took control in mid-1965.[121] Thiệu gradually outmaneuvered Kỳ and cemented his grip on power in fraudulent elections in 1967 and 1971.[122] Under this political instability, the communists began to gain ground. To support South Vietnam's struggle against the communist insurgency, the United States began increasing its contribution of military advisers, using the 1964 Gulf of Tonkin incident as a pretext for such intervention.[123] US forces became involved in ground combat operations in 1965, and at their peak they numbered more than 500,000.[124][125] The US also engaged in a sustained aerial bombing campaign. Meanwhile, China and the Soviet Union provided North Vietnam with significant material aid and 15,000 combat advisers.[116][117][126] Communist forces supplying the Việt Cộng carried supplies along the Hồ Chí Minh trail, which passed through the Kingdom of Laos.[127]

Việt Cộng guerrilla crossing a river in the Mekong Delta, 1966.

The communists attacked South Vietnamese targets during the 1968 Tết Offensive. Although the campaign failed militarily, it shocked the American establishment, and turned US public opinion against the war.[128] During the offensive, communist troops massacred over 3,000 civilians at Huế.[129][130] Facing an increasing casualty count, rising domestic opposition to the war, and growing international condemnation, the US began withdrawing from ground combat roles in the early 1970s. This process also entailed an unsuccessful effort to strengthen and stabilise South Vietnam.[131] Following the Paris Peace Accords of 27 January 1973, all American combat troops were withdrawn by 29 March 1973.[132] In December 1974, North Vietnam captured the province of Phước Long and started a full-scale offensive, culminating in the fall of Saigon on 30 April 1975.[133] South Vietnam was briefly ruled by a provisional government for almost eight years while under military occupation by North Vietnam.[134]

Reunification and reforms

Reunification parade following the fall of Saigon, with the city being renamed as Ho Chi Minh City, 1975.

On 2 July 1976, North and South Vietnam were merged to form the Socialist Republic of Vietnam.[135] The war left Vietnam devastated, with the total death toll standing at between 966,000 and 3.8 million.[136][137][138] In the aftermath of the war, under Lê Duẩn's administration, there were no mass executions of South Vietnamese who had collaborated with the US and the defunct South Vietnamese government, confounding Western fears.[139] However, up to 300,000 South Vietnamese were sent to re-education camps, where many endured torture, starvation and disease while being forced to perform hard labour.[140] The government embarked on a mass campaign of collectivisation of farms and factories.[141] In 1978, as a response towards the Khmer Rouge who had been invading and massacring Vietnamese residents in the border villages in the districts of An Giang and Kiên Giang,[142] the Vietnamese military invaded Cambodia and remove them from power after overtaking Phnom Penh.[143] The intervention was a success, resulting the establishment of a new pro-Vietnam socialist government, the People's Republic of Kampuchea which ruled until 1989.[144] This action however worsened relations with China, who had been supporting the Khmer Rouge where they later launched a brief incursion into northern Vietnam in 1979 and causing Vietnam to rely even more heavily on Soviet economic and military aid with the mistrust towards the Chinese government began to escalated.[145]

The Ho Chi Minh Mausoleum in the capital city of Hanoi, pictured in 2006.

At the Sixth National Congress of the Communist Party of Vietnam (CPV) in December 1986, reformist politicians replaced the "old guard" government with new leadership.[146][147] The reformers were led by 71-year-old Nguyễn Văn Linh, who became the party's new general secretary.[146] Linh and the reformers implemented a series of free-market reforms known as Đổi Mới ("Renovation") which carefully managed the transition from a planned economy to a "socialist-oriented market economy".[148][149] Though the authority of the state remained unchallenged under Đổi Mới, the government encouraged private ownership of farms and factories, economic deregulation and foreign investment, while maintaining control over strategic industries.[149][150] The Vietnamese economy subsequently achieved strong growth in agricultural and industrial production, construction, exports and foreign investment despite through these reforms also have caused a rise in income inequality and gender disparities.[151][152][153]

Geography

Vietnam geographical feature as seen from NASA satellite image in 2004.

Hoàng Liên Sơn mountain range in the north, en route to the highest summit of the country, the Fansipan.

Vietnam is located on the eastern Indochinese Peninsula between the latitudes 8° and 24°N, and the longitudes 102° and 110°E. It covers a total area of approximately 331,212 km2 (127,882 sq mi).[n 4] The combined length of the country's land boundaries is 4,639 km (2,883 mi), and its coastline is 3,444 km (2,140 mi) long.[154] At its narrowest point in the central Quảng Bình Province, the country is as little as 50 kilometres (31 mi) across, though it widens to around 600 kilometres (370 mi) in the north.[155] Vietnam's land is mostly hilly and densely forested, with level land covering no more than 20%. Mountains account for 40% of the country's land area,[156] and tropical forests cover around 42%.[157] The northern part of the country consists mostly of highlands and the Red River Delta. Fansipan (also called as Phan Xi Păng) which is located in Lào Cai Province is the highest mountain in Vietnam, standing 3,143 m (10,312 ft) high.[158]

Nature attractions in Vietnam, clockwise from top: Hạ Long Bay, Yến River and Bản-Giốc Waterfalls.

The Red River Delta in the north, a flat, roughly triangular region covering 15,000 km2 (5,792 sq mi),[159] is smaller but more intensely developed and more densely populated than the Mekong River Delta in the south. Once an inlet of the Gulf of Tonkin, it has been filled in over the millennia by riverine alluvial deposits.[160][161] The delta, covering about 40,000 km2 (15,444 sq mi), is a low-level plain no more than 3 metres (9.8 ft) above sea level at any point. It is criss-crossed by a maze of rivers and canals, which carry so much sediment that the delta advances 60 to 80 metres (196.9 to 262.5 ft) into the sea every year.[162][163] Southern Vietnam is divided into coastal lowlands, the mountains of the Annamite Range, and extensive forests. Comprising five relatively flat plateaus of basalt soil, the highlands account for 16% of the country's arable land and 22% of its total forested land.[164] The soil in much of southern part of Vietnam is relatively low in nutrients as a result of intense cultivation.[165] Several minor earthquakes have been recorded in the past with most occurred near the northern Vietnamese border in the provinces of Điện Biên, Lào Cai and Sơn La while some are recorded in the offshore of the central part of the country.[166][167]

Climate

Due to differences in latitude and the marked variety in topographical relief, the climate tends to vary considerably for each region.[168] During the winter or dry season, extending roughly from November to April, the monsoon winds usually blow from the northeast along the Chinese coast and across the Gulf of Tonkin, picking up considerable moisture.[169] The average annual temperature is generally higher in the plains than in the mountains, especially in southern Vietnam compared to the north. Temperatures vary less in the southern plains around Ho Chi Minh City and the Mekong Delta, ranging from between 21 and 35 °C (69.8 and 95.0 °F) over the course of the year.[170] In Hanoi and the surrounding areas of Red River Delta, the temperatures are much lower between 15 and 33 °C (59.0 and 91.4 °F)[170] while seasonal variations in the mountains and plateaus and in the northernmost are much more dramatic, with temperatures varying from 3 °C (37.4 °F) in December and January to 37 °C (98.6 °F) in July and August.[171] As Vietnam received high rain precipitation with an average amount of rainfall from 1,500 millimitres to 2,000 millimetres during the monsoon seasons, this often causes flood especially in the cities with poor drainage system.[172] The country also are not exempted from being affected by tropical depressions, tropical storms and typhoon.[172]

Biodiversity

Native species in Vietnam, clockwise from top-right: crested argus, red-shanked douc, Indochinese leopard, saola.

As the country is located inside the Indomalayan realm, Vietnam is one of twenty-five countries considered to possess a uniquely high level of biodiversity as also been stated in the country National Environmental Condition Report in 2005.[173] It is ranked 16th worldwide in biological diversity, being home to approximately 16% of the world's species. 15,986 species of flora have been identified in the country, of which 10% are endemic, while Vietnam's fauna include 307 nematode species, 200 oligochaeta, 145 acarina, 113 springtails, 7,750 insects, 260 reptiles, 120 amphibians, 840 birds and 310 mammals, of which 100 birds and 78 mammals are endemic.[173] Vietnam has two World Natural Heritage Sites, the Hạ Long Bay and Phong Nha-Kẻ Bàng National Park together with nine biosphere reserves including Cần Giờ Mangrove Forest, Cát Tiên, Cát Bà, Kiên Giang, the Red River Delta, Mekong Delta, Western Nghệ An, Cà Mau and Cu Lao Cham Marine Park.[174][175][176]

Pink lotus, widely regarded by Vietnamese as the national flower of the country which symbolising beauty, commitment, health, honour and knowledge.[177][178]

Vietnam is furthermore home to 1,438 species of freshwater microalgae, constituting 9.6% of all microalgae species, as well as 794 aquatic invertebrates and 2,458 species of sea fish.[173] In recent years, 13 genera, 222 species, and 30 taxa of flora have been newly described in Vietnam.[173] Six new mammal species, including the saola, giant muntjac and Tonkin snub-nosed monkey have also been discovered, along with one new bird species, the endangered Edwards's pheasant.[179] In the late 1980s, a small population of Javan rhinoceros was found in Cát Tiên National Park. However, the last individual of the species in Vietnam was reportedly shot in 2010.[180] In agricultural genetic diversity, Vietnam is one of the world's twelve original cultivar centres. The Vietnam National Cultivar Gene Bank preserves 12,300 cultivars of 115 species.[173] The Vietnamese government spent US$49.07 million on the preservation of biodiversity in 2004 alone, and has established 126 conservation areas, including 30 national parks.[173]

Environment

Thung Nham Bird Sanctuary in Ninh Bình Province of northern Vietnam housing more than 40 species of birds and more than 100 flora species, an example of ongoing conservation efforts towards habitat life in the country.[181]

In Vietnam, poaching had become a main issue for their wildlife. Since 2000, a non-governmental organisation (NGO) called Education for Nature - Vietnam have been founded to instill the importance of wildlife conservation in the country.[182] Following this, the seeds of the conservation movement starting to bloom with the foundation of another NGO called GreenViet by Vietnamese youngsters for the enforcement of wildlife protection. Through collaboration between the NGO and local authorities, many local poaching syndicates managed to be crippled with the arrestment of their leaders.[182] As Vietnam have also become the main destination for rhinoceros horn illegal export from South Africa, a study in 2018 found the demands are due to medical and health-related reasons.[183] The main environmental concern that persists in Vietnam until present is the chemical herbicide legacy of Agent Orange that causing birth defects and many health problems towards Vietnamese residents especially in the southern and central areas that was affected most by the chemicals with nearly 4.8 million Vietnamese have been exposed.[184][185][186] In 2012, approximately 50 years after the war,[187] the United States began to start a US$43 million joint clean up project in the former chemical storage areas in Vietnam that was heavily affected with each clearance will be done through several phases.[185][188] Following the completion of the first phase in Đà Nẵng in late 2017,[189] the United States announced its further commitment to clean other sites especially in another heavily impact site of Biên Hòa which is four times larger than the previous site with an additional estimate cost of $390 million.[190]

The Vietnamese government spends over VNĐ10 trillion each year ($431.1 million) for monthly allowance and physical rehabilitation of the Vietnamese victims caused by the chemicals.[191] In 2018, Japanese Engineering Group, Shimizu Corporation also working with Vietnamese military to built a plant in Vietnam for the treatment of Agent Orange polluted soils with the plant construction costs to be funded by the company itself.[192][193] One of the long-term plan to restore the southern Vietnam damaged ecosystems is through reforestation efforts which the Vietnamese government having done since the end of the war, starting with the replantation of mangrove forests in the Mekong Delta regions and in Cần Giờ outside of the main city where mangroves are important to prevent more serious flooding during the monsoon seasons.[194] Apart from herbicide problems, arsenic exposure to ground water in the Mekong Delta and Red River Delta also become a major concern,[195][196] along with unexploded ordnance (UXO) that poses dangers towards human and habitat life as another bitter legacy from the long wars.[197] As part of the continuous campaign for demining/removal of UXO, various international bomb removal agency including those from the United Kingdom,[198]Denmark,[199]South Korea[200] as well the United States[201] itself has providing help in the process with the Vietnam government spends over VNĐ1 trillion ($44 million) annually on demining operations and another hundreds billions of đồng for treatment, assistance, rehabilitation, vocational training and resettlement for the victims of UXOs.[202] Apart from the explosive removal from the legacy of civil war, the neighbouring Chinese government also has removed 53,000 land mines and explosives from the legacy of war between the two countries in an area of 18.4 square kilometres in neighbouring province of Yunnan between the China–Vietnam border in 2017.[203]

Government and politics

The Presidential Palace in Hanoi, formerly the Palace of The Governor-General of French Indochina.

Vietnam is a unitary Marxist-Leninist one-party socialist republic, one of the two communist states (the other being Laos) in Southeast Asia.[204] Although Vietnam remains officially committed to socialism as its defining creed, its economic policies have grown increasingly capitalist,[205][206] with The Economist characterising its leadership as "ardently capitalist communists".[207] Under the constitution, the Communist Party of Vietnam (CPV) asserts their role in all branches of politics and society in the country.[204] The President is the elected head of state and the commander-in-chief of the military, serving as the Chairman of the Council of Supreme Defence and Security, holds the second highest office in Vietnam as well as performing executive functions and state appointments and setting policy.[204]

@media all and (max-width:720px){.mw-parser-output .tmulti>.thumbinner{width:100%!important;max-width:none!important}.mw-parser-output .tmulti .tsingle{float:none!important;max-width:none!important;width:100%!important;text-align:center}}

Nguyễn Phú Trọng

General Secretary & President

Nguyễn Xuân Phúc

Prime Minister

Nguyễn Thị Kim Ngân

National Assembly Chairperson

The General Secretary of the CPV performs numerous key administrative functions, controlling the party's national organisation.[204] The Prime Minister is the head of government, presiding over a council of ministers composed of five deputy prime ministers and the heads of 26 ministries and commissions. Only political organisations affiliated with or endorsed by the CPV are permitted to contest elections in Vietnam. These include the Vietnamese Fatherland Front and worker and trade unionist parties.[204]

The National Assembly of Vietnam building in Hanoi

The National Assembly of Vietnam is the unicameral legislature of the state, composed of 498 members.[208] The legislature is open to all parties. Headed by a Chairman, it is superior to both the executive and judicial branches, with all government ministers being appointed from members of the National Assembly.[204] The Supreme People's Court of Vietnam, headed by a Chief Justice, is the country's highest court of appeal, though it is also answerable to the National Assembly. Beneath the Supreme People's Court stand the provincial municipal courts and numerous local courts. Military courts possess special jurisdiction in matters of national security. Vietnam maintains the death penalty for numerous offences.[209]

Foreign relations

Throughout its history, Vietnam's main foreign relationship has been with various Chinese dynasties.[210] Following the partition of Vietnam, the relations are divided between relations with Eastern Bloc for North Vietnam while Western Bloc for South Vietnam.[210] Despite the differences, Vietnam's sovereign principles and insistence on cultural independence have been laid down in numerous documents over the centuries since before its independence, such as the 11th-century patriotic poem "Nam quốc sơn hà" and the 1428 proclamation of independence "Bình Ngô đại cáo". Though China and Vietnam are now formally at peace,[210]significant territorial tensions in the South China Sea remain between the two countries.[211] Vietnam holds membership of 63 international organisations, including the United Nations (UN), Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), Non-Aligned Movement (NAM), International Organisation of the Francophonie (La Francophonie) and World Trade Organization (WTO). It also maintains relations with over 650 non-government organisations.[212] Until 2010, Vietnam had established diplomatic relations with 178 countries.[213]

Vietnam current foreign policy is to implement consistently the policy of independence, self-reliance, peace, co-operation and development as well the openness and diversification/multilateralisation of international relations,[214][215] with the country further declares itself as a friend and partner of all countries in the international community regardless of their political affiliation by actively taking part in international and regional co-operation especially in country development.[149][214] Since 1990s, several key steps had been taken by Vietnam to restore diplomatic ties with Western countries.[216] Relations with the United States began to improved in August 1995 with both nations upgraded their liaison offices to an embassy status.[217] As diplomatic ties between the two nations grew, the United States opened a consulate general in Ho Chi Minh City while Vietnam opened its consulate in San Francisco. Full diplomatic relations were also restored with New Zealand who opened its embassy in Hanoi in 1995,[218] while Vietnam established an embassy in Wellington in 2003.[219]Pakistan also reopened its embassy in Hanoi in October 2000 with Vietnam reopened their embassy in Islamabad in December 2005 and trade office in Karachi in November 2005.[220][221] In May 2016, US President Barack Obama further normalised relations with Vietnam after he announced the lifting of an arms embargo on sales of lethal arms to Vietnam.[222]

Military

Examples of the Vietnam People's Armed Forces weaponry assets. Clockwise from top right: T-54B tank, Sukhoi Su-27UBK fighter aircraft, Vietnam Coast Guard Hamilton-class cutter, and Vietnam People's Army chemical corps with Type 56.

The Vietnam People's Armed Forces consists of the Vietnam People's Army, the Vietnam People's Public Security and the Vietnam Civil Defence Force. The Vietnam People's Army (VPA) is the official name for the active military services of Vietnam, and is subdivided into the Vietnam People's Ground Forces, the Vietnam People's Navy, the Vietnam People's Air Force, the Vietnam Border Defence Force and the Vietnam Coast Guard. The VPA has an active manpower of around 450,000, but its total strength, including paramilitary forces, may be as high as 5,000,000.[223] In 2015, Vietnam's military expenditure totalled approximately US$4.4 billion, equivalent to around 8% of their total government spending.[224] Joint military exercises and war games also being held with Brunei,[225]India,[226]Japan,[227] Laos,[228]Russia,[229][230]Singapore[225] and the United States.[231]

Administrative divisions

Vietnam is divided into 58 provinces (Vietnamese: tỉnh, from the Chinese 省, shěng).[232] There are also five municipalities (thành phố trực thuộc trung ương), which are administratively on the same level as provinces.

Red River Delta Bắc Ninh | Northeast Bắc Giang | Northwest Điện Biên | North Central Coast Hà Tĩnh |

Central Highlands Đắk Lắk | South Central Coast Bình Định | Southeast Bà Rịa–Vũng Tàu | Mekong Delta An Giang |

The provinces are subdivided into provincial municipalities (thành phố trực thuộc tỉnh), townships (thị xã) and counties (huyện), which are in turn subdivided into towns (thị trấn) or communes (xã). The centrally controlled municipalities are subdivided into districts (quận) and counties, which are further subdivided into wards (phường).

Economy

| Share of world GDP (PPP)[6] | |

|---|---|

| Year | Share |

| 1980 | 0.18% |

| 1990 | 0.23% |

| 2000 | 0.32% |

| 2010 | 0.43% |

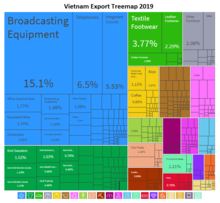

Tree map of Vietnam export in 2012

Throughout the history of Vietnam, its economy has been largely on agriculture based on wet rice cultivation.[233] There is also an industry for bauxite mining in central Vietnam, an important material for the production of aluminium.[234] Since reunification, the country economy is shaped primarily by the Communist Party of Vietnam (CPV) through the Five Year Plans which are being decided from the plenary sessions of the Central Committee and national congresses.[235] The collectivisation of farms, factories and capital goods was carried out as components in establishing central planning, with millions of people working in state enterprises. Despite strict state control, Vietnam's economy continued to be plagued with inefficiency and corruption in state-owned enterprises, poor quality and underproduction.[236][237][238] With the decrease of Soviet economic aid as the main trading partners for Vietnam following the erosion of the Eastern bloc in the late 1980s and subsequent Soviet Union collapse in addition to the negative impacts from the post-war trade embargo imposed by the United States,[239][240] Vietnam began to liberalise its trade by devaluing its exchange rate to increase exports and embark on a policy of economic development.[241]

Ho Chi Minh City, the financial centre of Vietnam with its tallest skyscraper, the Landmark 81, at night.

In 1986, the Sixth National Congress of the CPV introduced socialist-oriented market economic reforms as part of the Đổi Mới reform program with private ownership began to be encouraged in industries, commerce and agriculture and state enterprises were restructured to operate under market constraints,[242][243] resulting the old-fashioned five-year economic plans are being replaced with socialist market mechanism.[244] As a result of these reforms, Vietnam achieved around 8% annual Gross domestic product (GDP) growth between 1990 and 1997,[245][246] with the United States also ended its economic embargo against Vietnam in early 1994.[247] Despite the 1997 Asian financial crisis affecting Vietnam and causing economic slow down to 4-5% growth per annum, its economy began to recover in 1999,[242] with growth at an annual rate of around 7% from 2000 to 2005 and making the country as one of the world's fastest growing economies.[248][249] According to General Statistics Office of Vietnam (GSO), growth remained strong even in the face of the late-2000s global recession, holding at 6.8% in 2010, although Vietnam's year-on-year inflation rate hit 11.8% in December 2010 with the country currency, the Vietnamese đồng are being devalued three times.[250][251]

VinFast company is a Vietnamese car manufacturer.

Deep poverty which defined as the percentage of the population living on less than $1 per day has declined significantly in Vietnam and the relative poverty rate is now less than that of China, India and the Philippines.[252] This decline in the poverty rate can be attributed to equitable economic policies aimed at improving living standards and preventing the rise of inequality;[253] these policies have included egalitarian land distribution during the initial stages of the Đổi Mới program, investment in poorer remote areas, and subsidising of education and healthcare.[254][255] Since the early 2000s, Vietnam has applied sequenced trade liberalisation, a two-track approach opening some sectors of the economy to international markets.[253][256] Manufacturing, information technology and high-tech industries now form a large and fast-growing part of the national economy. Though Vietnam is a relative newcomer to the oil industry, it is currently the third-largest oil producer in Southeast Asia with a total 2011 output of 318,000 barrels per day (50,600 m3/d).[257] In 2010, Vietnam was ranked as the 8th largest crude petroleum producers in the Asia and Pacific region.[258] The United States was the country that purchased the highest amount of Vietnam's exports,[259] while goods from China were the most popular Vietnamese import.[260] As a result of several land reform measures, Vietnam has become a major exporter of agricultural products. It is now the world's largest producer of cashew nuts, with a one-third global share;[261] the largest producer of black pepper, accounting for one-third of the world's market;[262] and the second-largest rice exporter in the world after Thailand since the 1990s.[263] Subsequently, Vietnam is also the world's second largest exporter of coffee.[264]

The Golden Bridge in Đà Nẵng of central Vietnam, tourism have recently become one of the key component for the country economy.[265]

The country has the highest proportion of land use for permanent crops together with other nations in the Greater Mekong Subregion.[266] Other primary exports include tea, rubber and fishery products although agriculture's share of Vietnam's GDP has fallen in recent decades, declining from 42% in 1989 to 20% in 2006 as production in other sectors of the economy has risen.[267] According to a December 2005 forecast by Goldman Sachs, the Vietnamese economy will become the world's 21st-largest by 2025,[268] with an estimated nominal GDP of $436 billion and a nominal GDP per capita of $4,357.[269] Based on a findings by International Monetary Fund (IMF) in 2012, the unemployment rate in Vietnam stood at 4.46%.[6] Along the same year, Vietnam's nominal GDP reached US$138 billion, with a nominal GDP per capita of $1,527.[6] The HSBC also predicted that Vietnam's total GDP would surpass those of Norway, Singapore and Portugal by 2050.[269][270] Another forecast by PricewaterhouseCoopers in 2008 stating that Vietnam may be the fastest-growing of the world's emerging economies by 2025, with a potential growth rate of almost 10% per annum in real dollar terms.[271] Apart from the primary sector economy, tourism has contributed significantly to Vietnam's economic growth with 7.94 million foreign visitors are recorded in 2015.[265]

Science and technology

A Vietnamese-made TOPIO 3.0 humanoid ping-pong playing robot displayed during the 2009 International Robot Exhibition (IREX) in Tokyo.[272][273]

Zalo, the country main social messaging apps with over 30 million users in 2015.[274]

In 2010, Vietnam's total state spending on science and technology equalled around 0.45% of its GDP.[275] Since the dynastic era, Vietnamese scholars has developed many academic fields especially in social sciences and humanities. Vietnam has a millennium-deep legacy of analytical histories, such as the Đại Việt sử ký toàn thư of Ngô Sĩ Liên. Vietnamese monks led by the abdicated Emperor Trần Nhân Tông developed the Trúc Lâm Zen branch of philosophy in the 13th century.[276]Arithmetics and geometry have been widely taught in Vietnam since the 15th century, using the textbook Đại thành toán pháp by Lương Thế Vinh as a basis. Lương Thế Vinh introduced Vietnam to the notion of zero, while Mạc Hiển Tích used the term số ẩn (en: "unknown/secret/hidden number") to refer to negative numbers. Vietnamese scholars furthermore produced numerous encyclopaedias, such as Lê Quý Đôn's Vân đài loại ngữ. In modern times, Vietnamese scientists have made many significant contributions in various fields of study, most notably in mathematics. Hoàng Tụy pioneered the applied mathematics field of global optimisation in the 20th century,[277] while Ngô Bảo Châu won the 2010 Fields Medal for his proof of fundamental lemma in the theory of automorphic forms.[278][279] Since the establishment of Vietnam Academy of Science and Technology (VAST) by the government in 1975, the country is working to develop its first national space flight program especially after the completion of the infrastructure of Vietnam Space Centre (VSC) in 2018.[280][281] Vietnam has also made significant advances in the development of robots, such as the TOPIO humanoid model.[272][273] Vietnam's main messaging apps, Zalo is developed by Vương Quang Khải, a Vietnamese hacker who later work with the country largest information technology service company, the FPT Group.[282]

Vietnamese science students making an experiment in their university lab.

According to the UNESCO Institute for Statistics, Vietnam devoted 0.19% of its GDP for science research and development in 2011.[283] Between 2005 and 2014, the number of scientific publications recorded in Thomson Reuters' Web of Science increased at a rate well above the average for Southeast Asia, albeit from a modest starting point.[284] Publications focus mainly on life sciences (22%), physics (13%) and engineering (13%), which is consistent with recent advances in the production of diagnostic equipment and shipbuilding.[284] Almost 77% of all papers published between 2008 and 2014 had at least one international co-author. The autonomy which Vietnamese research centres have enjoyed since the mid-1990s has enabled many of them to operate as quasi-private organisations, providing services such as consulting and technology development.[284] Some have 'spun off' from the larger institutions to form their own semi-private enterprises, fostering the transfer of public sector science and technology personnel to these semi-private establishments. One comparatively new university, the Tôn Đức Thắng University which built in 1997 has already set up 13 centres for technology transfer and services that together produce 15% of university revenue. Many of these research centres serve as valuable intermediaries bridging public research institutions, universities and firms.[284]

Infrastructure

Transport

1. Passenger boarding a train of Vietnam Railways.

2. Airbus A321 aeroplane of the Vietnam Airlines at the Tan Son Nhat International Airport.

3. Vietnamese junk in Hạ Long Bay inside the Gulf of Tonkin.

4. HCMC–LT–DG Expressway of the North–South.

Much of Vietnam's modern transportation network traced its roots since the French colonial era where it was used to facilitate the transportation of raw materials to main ports before being extensively expanded and modernised following the partition of Vietnam.[285] Vietnam's road system includes national roads administered at the central level, provincial roads managed at the provincial level, district roads managed at the district level, urban roads managed by cities and towns and commune roads managed at the commune level.[286] In 2010, Vietnam road system has a total length of about 188,744 kilometres (117,280 mi) with 93,535 kilometres (58,120 mi) are asphalt road comprising national, provincial and district roads.[286] The national road system length is about 15,370 kilometres (9,550 mi) with 15,085 kilometres (9,373 mi) of its length are paved, the provincial road has around 27,976 kilometres (17,383 mi) paved road while district road has 50,474 kilometres (31,363 mi) paved road.[286]

Bicycles, motorcycles and motor scooters remain the most popular forms of road transport in the country as one of the legacy of French through transportation although the number of privately owned cars have been rising in recent years.[287] Public buses operated by private companies are the main mode of long-distance travel for much of the population. Road accidents remain the major safety issue in Vietnamese transportation with an average of 30 people lost their lives daily,[288] while traffic congestion is a growing problem in both major cities of Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City especially with the growing of individual car ownership.[289][290] Vietnam's primary cross-country rail service is the Reunification Express from Ho Chi Minh City to Hanoi with a distance of nearly 1,726 kilometres (1,072 mi).[291] From Hanoi, railway lines branch out to the northeast, north and west; the eastbound line runs from Hanoi to Hạ Long Bay, the northbound line from Hanoi to Thái Nguyên, and the northeast line from Hanoi to Lào Cai. In 2009, Vietnam and Japan signed a deal to build a high-speed railway by using the technology of Japanese Shinkansen;[292] numerous Vietnamese engineers were later sent to Japan to receive training in the operation and maintenance of high-speed trains.[293] The planned railway will be a 1,545 kilometres (960 mi) long express route serving a total of 23 stations including in Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City with 70% of its route will running on bridges and through underground tunnels,[294][295] while the trains will travelling at a maximum speed of 350 kilometres (220 mi) per hour.[295][296] The plan for the country first high-speed rail however are being postponed with the Vietnamese government made a decision to putting the main priority on the development of both Hanoi Metro and Ho Chi Minh City Metro as well the expansion of road networks instead.[291][297][298]

Container port in Hải Phòng

Vietnam operates 20 major civil airports, including three international gateways: Noi Bai in Hanoi, Da Nang International Airport in Đà Nẵng and Tan Son Nhat in Ho Chi Minh City. Tan Son Nhat is the nation's largest airport by which it handling the majority of international passenger traffic.[299] According to a state-approved plan, Vietnam will have another seven international airports by 2015, these include Vinh International Airport, Phu Bai International Airport, Cam Ranh International Airport, Phu Quoc International Airport, Cat Bi International Airport, Can Tho International Airport and Long Thanh International Airport. The planned Long Thanh International Airport will have an annual service capacity of 100 million passengers once it becomes fully operational in 2025.[300]Vietnam Airlines, the state-owned national airline maintains a fleet of 86 passenger aircraft and aims to operate 170 by 2020.[301] Several private airlines are also in operation in Vietnam, including Air Mekong, Jetstar Pacific Airlines, VASCO and VietJet Air. As a coastal country, Vietnam has many major sea ports, including Cam Ranh, Đà Nẵng, Hải Phòng, Ho Chi Minh City, Hạ Long, Qui Nhơn, Vũng Tàu, Cửa Lò and Nha Trang. Further inland, the country's extensive network of rivers play a key role in rural transportation with over 47,130 kilometres (29,290 mi) of navigable waterways carrying ferries, barges and water taxis.[302]

Energy

Sơn La Dam in northern Vietnam, the largest hydroelectric dam in Southeast Asia.[303]

Vietnam's energy sector is largely dominated by Electricity of Vietnam (EVN) nationwide. As of 2017, EVN contributed about 61.4% of the country power generation system with a total power capacity of 25,884 MW.[304] Other energy source are distributed by PetroVietnam (4,435 MW), Vinacomin (1,785 MW) and by build–operate–transfer (BOT) with other investors (10,031 MW).[305] Most of the powers are generated from either hydropower, fossil fuel power such as coal, oil and gas while the remaining are from diesel, small hydropower and renewable energy.[305] The Vietnamese government also previously planning to develop their first nuclear reactor as the path to establish another source of electric energy from nuclear power but the plan was abandoned in late 2016 with a majority oppose vote through the country National Assembly due to large concerns from Vietnamese society over radioactive contamination.[306] The household gas sector in Vietnam is dominated by PetroVietnam which controls nearly 70% of the country domestic market for liquefied petroleum gas (LPG).[307] Since 2011, the company also operating five renewable energy power plants including the Nhơn Trạch 2 Thermal Power Plant (750 MW), Phú Quý Wind Power Plant (6 MW), Hủa Na Hydro-power Plant (180 MW), Dakdrinh Hydro-power Plant (125 MW) and Vũng Áng 1 Thermal Power Plant (1,200 MW).[308] According to statistics by the British Petroleum (BP), Vietnam is listed among the 52 countries that have oil and gas potential in the world with proven crude oil reserves of the country in 2015 were approximately 4.4 billion barrels and ranked first place in Southeast Asia, while the proven gas reserves were about 0.6 trillion cubic metres (tcm) and ranked the third place in Southeast Asia after Indonesia and Malaysia.[309]

Health

Franco-Vietnamese Hospital in District 7, Ho Chi Minh City

By 2015, 97% of the population had access to improved water sources.[310] In 2016, Vietnam's national life expectancy stood at 80.9 years for women and 71.5 for men, and the infant mortality rate was 17 per 1,000 live births.[7][311][312] Despite these improvements, malnutrition is still common in the rural provinces.[153] Since the partition, North Vietnam has established a public health system that reached down to the hamlet level.[313] After the national reunification in 1975, a nationwide health service was established.[153] In the late 1980s, the quality of healthcare declined to some degree as a result of budgetary constraints, a shift of responsibility to the provinces and the introduction of charges.[254] Inadequate funding has also contributed to a shortage of nurses, midwives and hospital beds; in 2000, Vietnam had only 24.7 hospital beds per 10,000 people before declining to 23.7 in 2005 as stated in the annual report of Vietnamese Health Ministry.[314] The controversial use of herbicides as a chemical weapon by the US military during the war has left tangible, long-term impacts upon the Vietnamese people that still persists in the country until present.[315][316] For instance, it led to 3 million Vietnamese people suffering health problems, one million birth defects caused directly by exposure to the chemical and 24% of the area of Vietnam being defoliated.[317]

Since the early 2000s, Vietnam has made significant progress in combating malaria, with the malaria mortality rate falling to about 5% of its 1990s equivalent by 2005, after the country introduced improved antimalarial drugs and treatment.[318]Tuberculosis (TB) cases however are on the rise which become the second most infectious diseases in the country after respiratory-related illness.[319] With an intensified vaccination program, better hygiene and foreign assistance, Vietnam hopes to reduce sharply the number of TB cases and annual new TB infections.[320] In 2004, government subsidies covering about 15% of health care expenses.[321] Along the same year, the United States announced that Vietnam would be one of 15 nations to receive funding as part of its global AIDS relief plan.[322] By the following year, Vietnam had diagnosed 101,291 human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) cases, of which 16,528 progressed to acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) with 9,554 have died.[323] The actual number of HIV-positive individuals is estimated to be much higher as on average as between 40–50 new infections are reported daily in the country. In 2007, 0.4% of the population is estimated to be infected with HIV and the figure has remained stable since 2005.[324] More global aid are being delivered through The Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria to fight the spread of the diseases in the country.[320] In September 2018, the Hanoi People's Committee urged the citizens of the country to stop eating dog and cat meat as it can cause other diseases like rabies and leptospirosis as more than 1,000 stores in the capital city of Hanoi are found to be selling both meats. The decision received positive comments among Vietnamese society on social media despite many still disagreed as it has been a habit that couldn't be resisted.[325]

Education

Indochina Medical College in Hanoi, the first modern university in Vietnam

Vietnam has an extensive state-controlled network of schools, colleges and universities and a growing number of privately run and partially privatised institutions. General education in Vietnam is divided into five categories: kindergarten, elementary schools, middle schools, high schools, and universities. A large number of public schools have been constructed across the country to raise the national literacy rate, which stood at 90% in 2008.[326] Most universities are located in major cities of Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City with the country education system continuously undergoing a series of reform by the government. Basic education in the country is relatively free for the poor although some families may still have trouble paying tuition fee for their children without some form of public or private assistance.[327] Regardless, school enrolment is among the highest in the world,[328][329] and the number of colleges and universities increased dramatically in the 2000s from 178 in 2000 to 299 in 2005. In higher education, the government provide subsidised loans for students through national bank although there are deep concerns about its access as well the burdens among students in repaying.[330][331] Since 1995, enrolment in higher education has grown tenfold to over 2.2 million with 84,000 lecturers and 419 institutions of higher education.[332] A number of foreign universities operate private campuses in Vietnam, including Harvard University (USA) and the Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology (Australia). The government's strong commitment to education has fostered significant growth but still need to be sustained to retain academics. In 2018, a decree on university autonomy to operate independently without a ministry control above their heads are in its final stages of approval with the government will continue to investing in education especially for the poor to have access on basic education.[333]

Demographics

| Population[5] | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Million | ||

| 1950 | 24.8 | ||

| 2000 | 80.3 | ||

| 2016 | 94.6 | ||

As of 2016[update], the population of Vietnam standing at approximately 94.6 million people.[5] The population had grown significantly from the 1979 census, which showed the total population of reunified Vietnam to be 52.7 million.[334] In 2012, the country's population was estimated at approximately 90.3 million.[335] Based on the 2009 census, 70.4% of the Vietnamese population are living in rural areas while only 29.6% living in urban areas although the average growth rate of the urban population have recently increasing which mainly attributed to migration and rapid urbanisation.[336] The dominant Viet or Kinh ethnic group constituted nearly 73.6 million people or 85.8% of the population,[335] with most of their population is concentrated mainly in the alluvial deltas and coastal plains of the country. As a majority ethnic group, the Kinh possess significant political and economic influence over the country.[337] Despite this, Vietnam is also home to other 54 ethnic minority groups, including the Hmong, Dao, Tày, Thai and Nùng.[335] Many ethnic minorities such as the Muong who are closely related to the Kinh dwell in the highlands which cover two-thirds of Vietnam's territory.[338]

Other uplanders in the north migrated from southern China between 1300s and 1800s.[339] Since the partition of Vietnam, the population of the Central Highlands was almost exclusively Degar (including over 40 tribal groups); however, the South Vietnamese government at the time enacted a program of resettling Kinh in indigenous areas.[340][341] The Hoa (ethnic Chinese) and Khmer Krom people are mainly lowlanders.[337][339] Throughout Vietnam history, many Chinese people mainly from South China migrated to the country as administrators, merchants and even refugees.[342] Since the reunification in 1976 with the increase of communist policies nationwide that resulting the nationalisation of property and subsequently causing many rich people property in the city especially among the Hoa in the south are being confiscated by the government, this has led many of them to leave Vietnam.[343][344] Furthermore, with the deteriorating Sino-Vietnamese relations as a result of border invasion by Chinese government in 1979 which added by doubtful among Vietnamese society on the Chinese government intention had indirectly causing more Hoa people in the north to leave the country.[342][345]

| Largest cities of Vietnam (2015)[346] | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | City | Province | Population |

| |||||

| 1 | Hồ Chí Minh City | Municipality Region | 8,244,400 | |||||||

| 2 | Hà Nội | Municipality Region | 7,379,300 | |||||||

| 3 | Hải Phòng | Municipality Region | 1,946,000 | |||||||

| 4 | Cần Thơ | Municipality Region | 1,238,300 | |||||||

| 5 | Biên Hòa | Đồng Nai | 1,104,495 | |||||||

| 6 | Đà Nẵng | Municipality Region | 1,007,700 | |||||||

| 7 | Nha Trang | Khánh Hòa | 393,218 | |||||||

| 8 | Buôn Ma Thuột | Đắk Lắk | 350,000 | |||||||

| 9 | Huế | Thừa Thiên-Huế | 337,554 | |||||||

| 10 | Vinh | Nghệ An | 330,000 | |||||||

Languages

Vietnamese language books in a bookstore in Ho Chi Minh City.

The official national language of the country is Vietnamese (Tiếng Việt), a tonal Austroasiatic languages (Mon–Khmer) which is spoken by the majority of the population. In its early history, Vietnamese writing used Chinese characters before a different meaning set of Chinese characters known as Chữ nôm developed between the 7th–13th century.[347][348][349] The folk epic Truyện Kiều ("The Tale of Kieu", originally known as Đoạn trường tân thanh) by Nguyễn Du was written in Chữ nôm.[350]Quốc ngữ as the romanised Vietnamese alphabet used for spoken Vietnamese, was developed in the 17th century by the Jesuit Alexandre de Rhodes and several other Catholic missionaries by using the alphabets of Romance languages, particularly the Portuguese alphabet which later became widely used through Vietnamese institutions during the French colonial period.[347][351] Vietnam's minority groups speak a variety of languages, including Tày, Mường, Cham, Khmer, Chinese, Nùng and Hmong. The Montagnard peoples of the Central Highlands also speak a number of distinct languages as their language is derived from both the Austroasiatic and Malayo-Polynesian language groups.[352] In recent years, a number of sign languages have developed in the major cities.

The French language, a legacy of colonial rule, is spoken by many educated Vietnamese as a second language, especially among the older generation and those educated in the former South Vietnam, where it was a principal language in administration, education and commerce. Vietnam remains a full member of the International Organisation of the Francophonie (La Francophonie) and education has revived some interest in the language.[353]Russian and to a much lesser extent German, Czech and Polish are known among some northern Vietnamese whose families had ties with the Eastern Bloc during the Cold War.[354][355] With improved relations with Western countries and recent reforms in Vietnamese administration, English has been increasingly used as a second language and the study of English is now obligatory in most schools either alongside or in place of French.[356][357][358] The popularity of Japanese and Korean have also grown as the country's ties with other East Asian nations have strengthened.[359][360][361]

Religion

Religious worship places in Vietnam, clockwise from top-right: Trúc Lâm Yên Tử Buddhist Monastery, Notre-Dame Cathedral Catholic Basilica, Tây Ninh Holy See Caodaist Tower, Al-Noor Mosque Muslim Minaret and Cầu Hoahaoist Temple.

Religion in Vietnam (2014)[2]

Vietnamese folk religion or not religious population (73.2%)

Buddhism (12.2%)

Catholicism (6.8%)

Caodaism (4.8%)

Protestantism (1.5%)

Hoahaoism (1.4%)

Others (0.1%)

Under the Article 70 of the 1992 Constitution of Vietnam, every of the country citizens are given the rights for freedom of religion by the government;[362] by which every person can follow any religion or become irreligious with all religions are considered as equal with a condition that any religious beliefs cannot be misused to undermine state law and policies with their place of worship are protected under Vietnamese state law.[362][363] According to a survey in 2007, 81% of the Vietnamese people do not believe in a God.[364] Based on a new government findings in 2009, the number of religious people have increased by 932,000 people.[336] Through the latest official statistics presented by the Vietnamese government to United Nations special rapporteur in 2014,[2] the overall number of followers of recognised religions is about 24 million from the total population of almost 90 million.[2] Formally recognised religious communities include 11 million Buddhists, 6.2 million Catholics, 1.4 million Protestants, 4.4 million Caodaisms followers, 1.3 million Hoahaoism Buddhists as well as 75,000 Muslims, 7,000 Baha'ís and 1,500 Hindus.[2]

Mahāyāna is the dominant branch of Buddhism among the Kinh majority who follows religion, while Theravāda are practised in almost entirely by the Khmer minority. About 7% of the population are Christians, totalling around six million Roman Catholics and one million Protestants.[2] Catholicism have been introduced to Vietnam by nearby Portuguese missionaries (Jesuits) from Portuguese Macau and Malacca towards Annam and from remnants of the persecuted Japanese Catholic between the 16th and 17th centuries before being massively propagated by French missionaries aided by Spanish missionaries (Dominicans) from neighbouring Spanish East Indies towards Tonkin in the 19th and 20th centuries.[365][366][367] A significant number of Vietnamese people are also adherents of Caodaism, an indigenous folk religion which has structured itself on the model of the Catholic Church together with another Buddhist section of Hoahaoism.[368] Protestantism was only recently spread by American and Canadian missionaries throughout the modern civil war,[369] where it was largely accepted among the highland Montagnards of South Vietnam.[370] The largest Protestant churches are the Southern Evangelical Church of Vietnam (SECV) and the Evangelical Church of Vietnam North (ECVN) with around 770,000 of the country Protestants come from members of ethnic minorities.[369] Although it is one of the country minority religion and has a shorter history than Catholicism, Protestantism are found to be the country's fastest-growing religion, expanding at a rate of 600% in recent decades.[369][371] Several other minority faiths exist in Vietnam, these includes Bani, Sunni and non-denominational section of Islam which is primarily practised among the ethnic Cham minority,[372] though there were also a few Kinh adherents of Islam along with other minority adherents of Baha'is as well Hindus among the Cham's.[373][374]

Culture

Vietnam's culture has developed over the centuries from indigenous ancient Đông Sơn culture with wet rice cultivation as its economic base.[30][33] Some elements of the national culture have Chinese origins, drawing on elements of Confucianism, Mahāyāna Buddhism and Taoism in its traditional political system and philosophy.[375][376] Vietnamese society is structured around làng (ancestral villages);[377] all Vietnamese mark a common ancestral anniversary on the tenth day of the third lunar month.[378][379] The influence of Chinese culture such as the Cantonese, Hakka, Hokkien and Hainanese cultures are more evidenced in the north with the national religion of Buddhism is strongly entwined with popular culture.[380] In the central and southern part, traces of Champa and Khmer culture are evidenced through the remains of ruins, artefacts as well within their population as the successor of the ancient Sa Huỳnh culture.[381][382] In recent centuries, the influence of Western cultures have become popular among newer Vietnamese generations.[376]

Vietnamese traditional white school uniform for girls in the country, the áo dài with the addition of nón lá which is a type of conical hat.

The traditional focuses of Vietnamese culture are based on humanity (nhân nghĩa) and harmony (hòa); in which family and community values are highly regarded.[380] Vietnam reveres a number of key cultural symbols,[383] such as the Vietnamese dragon which is derived from crocodile and snake imagery; Vietnam's national father, Lạc Long Quân is depicted as a holy dragon.[378][384][385] The lạc is a holy bird representing Vietnamese national mother of Âu Cơ is another prominent symbol, while turtle, buffalo and horse images are also revered.[386] In the modern era, the cultural life of Vietnam has been deeply influenced by government-controlled media and cultural programs.[376] For many decades, foreign cultural influences especially those of Western origin were shunned. But since the recent reformation, Vietnam has seen a greater exposure to neighbouring Southeast Asian, East Asian as well to Western culture and media.[387]

The main Vietnamese formal dress, the áo dài is worn for special occasions such as in weddings and religious festivals. White áo dài is the required uniform for girls in many high schools across the country. Other examples of traditional Vietnamese clothing include the áo tứ thân, a four-piece woman's dress; the áo ngũ, a form of the thân in 5-piece form, mostly worn in the north of the country; the yếm, a woman's undergarment; the áo bà ba, rural working "pyjamas" for men and women; the áo gấm, a formal brocade tunic for government receptions; and the áo the, a variant of the áo gấm worn by grooms at weddings.[388][389] Traditional headwear includes the standard conical nón lá and the "lampshade-like" nón quai thao.[389][390] In tourism, a number of popular cultural tourist destinations include the former imperial capital of Hué, the World Heritage Sites of Phong Nha-Kẻ Bàng National Park, Hội An and Mỹ Sơn, coastal regions such as Nha Trang, the caves of Hạ Long Bay and the Marble Mountains.[391][392]

Literature