Philippine Drug War

| Philippine Drug War | |||

|---|---|---|---|

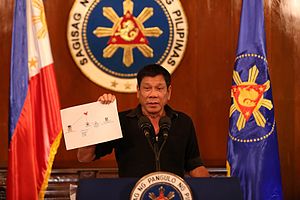

Duterte shows a diagram of drug syndicates at a press conference on July 7, 2016. | |||

| Date | July 1, 2016 – present (2 years, 8 months and 30 days) | ||

| Location | Philippines | ||

| Status | Ongoing[1] | ||

| Parties to the civil conflict | |||

| |||

| Lead figures | |||

| |||

| Casualties | |||

| |||

The Philippine Drug War refers to the drug policy of the Philippine government under President Rodrigo Duterte, who assumed office on June 30, 2016. According to former Philippine National Police Chief Ronald dela Rosa, the policy is aimed at "the neutralization of illegal drug personalities nationwide".[22] Duterte has urged members of the public to kill suspected criminals and drug addicts.[23] Research by media organizations and human rights groups has shown that police routinely execute unarmed drug suspects and then plant guns and drugs as evidence. Philippine authorities have denied misconduct by police.[24][25]

The policy has been widely condemned locally and internationally for the number of deaths resulting from police operations and allegations of systematic extrajudicial executions. The policy is supported by the majority of the local population, as well as by leaders or representatives of certain countries such as China, Japan and the United States.[26][27][9][28]

Estimates of the death toll vary. Officially, 5,104 drug personalities have been killed as of January 2019.[29] News organizations and human rights groups claim the death toll is over 12,000.[30][31] The victims included 54 children in the first year.[31][30] Opposition senators claimed in 2018 that over 20,000 have been killed.[32][33]

According to the official update "Real Numbers" released by the Philippine National Police and Philippine Drug Enforcement Agency, from July 1, 2016 to January 31, 2019, there were a total of 5,176 drug personalities killed in anti-drug operations, as well as 170,689 arrests[20] which include 295 government employees, 263 elected officials, and 69 uniformed personnel. 301 drug dens and laboratories have also been reported to have been dismantled,[21] and a total of 11,080 barangays have been declared "cleared" of illegal drugs.[20][21]

In February 2018, the International Criminal Court in The Hague announced a "preliminary examination" into killings linked to the Philippine Drug War since at least July 1, 2016.

Contents

1 Background

2 Major events

2.1 Early months

2.2 State of emergency

2.3 Senate committee

2.4 Temporary cessation of police drug operations

2.5 Amnesty International investigation

2.6 Arturo Lascañas

2.7 Allegations of police using hospitals to hide killings

2.8 Ozamiz raid, and death of Reynaldo Parojinog

2.9 "One-time, big-time" operations

2.10 Youth casualties

2.11 Reshuffling of the Caloocan City Police

2.12 Transfer of anti-drug operations to PDEA

2.13 Rodrigo Duterte's refutation to ASEAN representatives

2.14 2018

2.14.1 Consecutive assassinations of local government officials

2.15 2019

3 International Criminal Court

4 Reactions

4.1 Local

4.2 International

4.3 38-nation statement against the drug war

5 In popular media

5.1 Television

5.2 Music

5.3 Photography

5.4 Mobile gaming

6 See also

7 Notes

8 References

9 External links

Background

Rodrigo Duterte won the 2016 Philippine presidential election promising to kill tens of thousands of criminals, and urging people to kill drug addicts.[23] As Mayor of Davao City, Duterte was criticized by groups like Human Rights Watch for the extrajudicial killings of hundreds of street children, petty criminals and drug users carried out by the Davao Death Squad, a vigilante group with which he was allegedly involved.[34][35][36] Duterte has alternately confirmed and denied his involvement in the alleged Davao Death Squad killings.[37] Duterte has benefited from reports in the national media that he made Davao into one of the world's safest cities, which he cites as justification for his drug policy,[38][39][40] although national police data shows that the city has the highest murder rate and the second highest rape rate in the Philippines.[41][42]

Philippine anti-narcotic officials have admitted that Duterte uses flawed and exaggerated data to support his claim that the Philippines is becoming a "narco-state".[43] The Philippines has a low prevalence rate of drug users compared to the global average, according to the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC).[44] Duterte said in his state of the nation address that data from the Philippine Drug Enforcement Agency shows that there were 3 million drug addicts 2 to 3 years ago, which he said may have increased to 3.7 million. However, according to the Philippine Dangerous Drugs Board, the government drug policy-making body, 1.8 million Filipinos used illegal drugs (mostly cannabis) in 2015, the latest official survey published; a third of them had used illegal drugs only once in the past 13 months.[45][43]

Major events

Early months

In speeches made after his inauguration on June 30, Duterte urged citizens to kill suspected criminals and drug addicts. He said he would order police to adopt a shoot-to-kill policy, and would offer them a bounty for dead suspects.[23] In a speech to military leadership on July 1, Duterte told Communist rebels to "use your kangaroo courts to kill them to speed up the solution to our problem".[46] On July 2, the Communist Party of the Philippines stated that it "reiterates its standing order for the NPA to carry out operations to disarm and arrest the chieftains of the biggest drug syndicates, as well as other criminal syndicates involved in human rights violations and destruction of the environment" after its political wing Bagong Alyansang Makabayan accepted Cabinet posts in the new government.[47][48] On July 3, the Philippine National Police announced they had killed 30 alleged drug dealers since Duterte was sworn in as president on June 30.[49][50] They later stated they had killed 103 suspects between May 10 and July 7.[51] On July 9, a spokesperson of the president told critics to show proof that there have been human rights violations in the Drug War.[51][52] Later that day, the Moro Islamic Liberation Front announced it was open to collaborate with police in the Drug War.[53] On August 3, Duterte said that the Sinaloa cartel and the Chinese triad are involved in the Philippine drug trade.[54] On August 7, Duterte named more than 150 drug suspects including local politicians, police, judges, and military.[55][56][57] On August 8, the United States expressed concerns over the extrajudicial killings.[58]

A presidential spokesperson said that Duterte welcomed a proposed Congressional investigation into extrajudicial killings to be chaired by Senator Leila de Lima, his chief critic in the government.[54] On August 17, Duterte announced that de Lima had been having an affair with a married man, her driver, Ronnie Palisoc Dayan. Duterte claimed that Dayan was her collector for drug money, who had also himself been using drugs.[59]

In a news conference on August 21, Duterte announced that he had in his possession wiretaps and ATM records which confirmed his allegations. He stated: "What is really crucial here is that because of her [romantic] relationship with her driver which I termed 'immoral' because the driver has a family and wife, that connection gave rise to the corruption of what was happening inside the national penitentiary." Dismissing fears for Dayan's safety, he added, "As the President, I got this information … as a privilege. But I am not required to prove it in court. That is somebody else's business. My job is to protect public interest. She's lying through her teeth." He explained that he had acquired the new evidence from an unnamed foreign country.[60]

On August 18, United Nations human rights experts called on the Philippines to halt extrajudicial killings. Agnes Callamard, the UN Special Rapporteur on summary executions, stated that Duterte had given a "license to kill" to his citizens by encouraging them to kill.[61][62] In response, Duterte threatened to withdraw from the UN and form a separate group with African nations and China. Presidential spokesperson Ernesto Abella later clarified that the Philippines was not leaving the UN.[63] As the official death toll reached 1,800, a Congressional investigation of the killings chaired by de Lima was opened.[64]

On August 23, Chito Gascon, head of the Philippine Commission on Human Rights, told the Senate committee that the International Criminal Court may have jurisdiction over the mass killings.[65] On August 25, Duterte released a "drug matrix" supposedly linking government officials, including de Lima, with the New Bilibid Prison drug trafficking scandal.[66] De Lima stated that the "drug matrix" was like something drawn by a 12-year-old child. She added, "I will not dignify any further this so-called 'drug matrix' which, any ordinary lawyer knows too well, properly belongs in the garbage can."[67][68] On August 29, Duterte called on de Lima to resign and "hang herself".[69]

State of emergency

Following the September 2 bombing in Davao City that killed 14 people in the city's central business district, on September 3, 2016, Duterte declared a "state of lawlessness", and on the following day signed a declaration of a "state of national emergency on account of lawless violence in Mindanao".[70][71] The Armed Forces of the Philippines and the Philippine National Police were ordered to "suppress all forms of lawless violence in Mindanao" and to "prevent lawless violence from spreading and escalating elsewhere". Executive Secretary Salvador Medialdea said that the declaration "does not specify the imposition of curfews", and would remain in force indefinitely. He explained: "The recent incidents, the escape of terrorists from prisons, the beheadings, then eventually what happened in Davao. That was the basis."[72] The state of emergency has been seen as an attempt by Duterte to "enhance his already strong hold on power, and give him carte blanche to impose further measures" in the Drug War.[73]

At the 2016 ASEAN Summit, US President Barack Obama cancelled scheduled meetings with Duterte to discuss extrajudicial killings after Duterte referred to Obama as a "son of a whore".[74][75]

Senate committee

On September 19, 2016, the Senate voted 16-4 to remove de Lima from her position heading the Senate committee, in a motion brought by senator and boxer Manny Pacquiao.[76] Duterte's allies in the Senate argued that de Lima had damaged the country's reputation by allowing the testimony of Edgar Matobato. She was replaced by Senator Richard Gordon, a supporter of Duterte.[77] Matobato had testified that while working for the Davao Death Squad he had killed more than 50 people. He said that he had witnessed Duterte killing a government agent, and he had heard Duterte giving orders to carry out executions, including ordering the bombing of mosques as retaliation for an attack on a cathedral.[78]

Duterte told reporters that he wanted "a little extension of maybe another six months" in the Drug War, as there were so many drug offenders and criminals that he "cannot kill them all".[79][80] On the following day, a convicted bank robber and two former prison officials testified that they had paid bribes to de Lima. She denies the allegations.[81] In a speech on September 20, Duterte promised to protect police in the Drug War: .mw-parser-output .templatequote{overflow:hidden;margin:1em 0;padding:0 40px}.mw-parser-output .templatequote .templatequotecite{line-height:1.5em;text-align:left;padding-left:1.6em;margin-top:0}

For as long as I am the president, nobody but nobody – no military man or policeman will go to prison because they performed their duties. ... If [drug suspects] pull out a gun, kill them. If they don't, kill them, son of a whore so it's over, lest you lose the gun. I'll take care of you.[82][83]

At a press conference on September 30, Duterte appeared to make a comparison between the Drug War and The Holocaust.[84] He said that "Hitler massacred three million Jews. Now there are three million drug addicts. I’d be happy to slaughter them."[84] His remarks generated an international outcry. United States Secretary of Defense Ash Carter said the statement was "deeply troubling".[85][86] The German government told the Philippine ambassador that Duterte's remarks were "unacceptable."[87] On October 2, Duterte announced, "I apologize profoundly and deeply to the Jewish". He explained, "It's not really that I said something wrong but rather they don't really want you to tinker with the memory".[88][89]

At the beginning of October, a senior police officer told The Guardian that 10 "special ops" official police death squads had been operating, each consisting of 15 police officers. The officer said that he had personally been involved in killing 87 suspects, and described how the corpses had their heads wrapped in masking tape with a cardboard placard labelling them as a drug offender so that the killing would not be investigated, or they were dumped at the roadside ("salvage" victims). The chairman of the Philippines Commission on Human Rights, Chito Gascon, was quoted in the report: "I am not surprised, I have heard of this." The PNP declined to comment. The report stated: "although the Guardian can verify the policeman's rank and his service history, there is no independent, official confirmation for the allegations of state complicity and police coordination in mass murder."[90]

On October 28, Datu Saudi Ampatuan Mayor Samsudin Dimaukom and nine others, including his five bodyguards, were killed during an anti-illegal drug operation in Makilala, North Cotabato. According to police, the group were heavily armed and opened fire on police, who found sachets of methamphetamine at the scene. No police were injured.[91][92] Dimaukom was among the drug list named by Duterte on August 7; he had immediately surrendered, and then returned to Datu Saudi Ampatuan.[93]

On November 1, it was reported that the US State Department had halted the sale of 26,000 assault rifles to the PNP after opposition from the Senate Foreign Relations Committee due to concerns about human rights violations. A police spokesman said they had not been informed. PNP chief Ronald dela Rosa suggested China as a possible alternative supplier.[94][95] On November 7, Duterte reacted to the US decision to halt the sale by announcing that he was "ordering its cancellation".[96]

In the early morning of November 5, Mayor of Albuera, Rolando Espinosa Sr., who had been detained at Baybay City Sub-Provincial Jail for violation of the Comprehensive Dangerous Drugs Act of 2002, was killed in what was described as a shootout inside his jail cell with personnel from the Criminal Investigation and Detection Group (CIDG).[97] According to the CIDG, Espinosa opened fire on police agents who were executing a search warrant for "illegal firearms."[98] A hard drive of CCTV footage which may have recorded the shooting of Espinosa is missing, a provincial official said.[99] Espinosa had turned himself in to PNP after being named in Duterte's drug list in August.[100][101] He was briefly released but then re-arrested for alleged drug possession. The president of the National Union of People's Lawyers, Edre Olalia, told local broadcaster TV5 that the police version of events was "too contrived". He pointed out that a search warrant is not required to search a jail cell. "Such acts make a mockery of the law, taunt impunity and insult ordinary common sense." Espinosa was the second public official to be killed in the Drug War.[102][103]

Following the incident, on the same day, Senator Panfilo Lacson sought to resume the investigation of extrajudicial killings after it was suspended on October 3 by the Senate Committee on Justice and Human Rights.[104][105]

On November 28, Duterte appeared to threaten that human rights workers would be targeted: "The human rights [defenders] say I kill. If I say: 'Okay, I'll stop'. They [drug users] will multiply. When harvest time comes, there will be more of them who will die. Then I will include you among them because you let them multiply." Amnesty International Philippines stated that Duterte was "inciting hate towards anyone who expresses dissent on his war against drugs." The National Alliance against Killings Philippines stated: "His comment - that human rights is part of the drug problem and, as such, human rights advocates should be targeted too - can be interpreted as a declaration of an open season on human rights defenders".[106]

On December 5 Reuters reported that 97% of drug suspects shot by police died, far more than in other countries with drug-related violence. They also stated that police reports of killings are "remarkably similar", involving a "buy-bust" operation in which the suspect panics and shoots at the officers, who return fire, killing the suspect, and report finding a packet of white powder and a .38 caliber revolver, often with the serial number removed.

The figures pose a powerful challenge to the official narrative that the Philippines police are only killing drug suspects in self-defense. These statistics and other evidence amassed by Reuters point in the other direction: that police are pro-actively gunning down suspects.[107]

On December 8, the Senate Committee on Justice and Human Rights issued a report stating that there was "no evidence sufficient to prove that a Davao Death Squad exists", and "no proof that there is a state-sponsored policy to commit killings to eradicate illegal drugs in the country." Eleven senators signed the report, while senators Leila De Lima, JV Ejercito, Antonio Trillanes IV and Senate Minority Leader Ralph Recto did not sign the report or did not subscribe to its findings.[108]

Temporary cessation of police drug operations

Following criticism of the police over the kidnapping and killing of Jee Ick-Joo, a South Korean businessman, Duterte ordered the police to suspend drug-related operations while ordering the military and the Philippine Drug Enforcement Agency to continue drug operations.

Amnesty International investigation

On January 31, 2017, Amnesty International published a report of their investigation of 59 drug-related killings in 20 cities and towns, "If you are poor you are killed": Extrajudicial Executions in the Philippines' "War on Drugs", which "details how the police have systematically targeted mostly poor and defenceless people across the country while planting 'evidence', recruiting paid killers, stealing from the people they kill and fabricating official incident reports." They stated: "Amnesty International is deeply concerned that the deliberate, widespread and systematic killings of alleged drug offenders, which appear to be planned and organized by the authorities, may constitute crimes against humanity under international law."[7]

A police officer with the rank of Senior Police Officer 1, a ten-year veteran of a Metro Manila anti-illegal drugs unit, told AI that police are paid 8,000 pesos (US $161) to 15,000 pesos (US $302) per "encounter" (the term used for extrajudicial executions disguised as legitimate operations); there is no payment for making arrests. He said that some police also receive a payment from the funeral home they send the corpses to. Hitmen hired by police are paid 5,000 pesos (US $100) for each drug user killed and 10,000 to 15,000 pesos (US $200–300) for each "drug pusher" killed, according to two hitmen interviewed by AI.[7]

Family members and witnesses repeatedly contested the police description of how people were killed. Police descriptions bore striking similarities from incident to incident; official police reports in several cases documented by Amnesty International claim the suspect’s gun “malfunctioned” when he tried to fire at police, after which they shot and killed him. In many instances, the police try to cover up unlawful killings or ensure convictions for those arrested during drug-related operations by planting “evidence” at crime scenes and falsifying incident reports—both practices the police officer said were common.

— Amnesty International report “If you are poor you are killed”: Extrajudicial Executions in the Philippines’ “War on Drugs”[109]

The report makes a series of recommendations to Duterte and government officials and departments. If certain key steps are not swiftly taken, it recommends that the International Criminal Court "initiate a preliminary examination into unlawful killings in the Philippines’s violent anti-drug campaign and related crimes under the Rome Statute, including the involvement of government officials, irrespective of rank and status."[109]

The Guardian and Reuters stated that the report added to evidence they had published previously about police extrajudicial executions. Presidential spokesman Ernesto Abella responded to the report, saying that Senate committee investigations proved that there had been no state-sponsored extrajudicial killings.[110][111] In an interview on February 4, Duterte told a reporter that Amnesty International was "so naive and so stupid", and "a creation of [George] Soros". He asked, "Is that the only thing you [de Lima] can produce? The report of Amnesty?"[112]

De Lima was jailed on February 24, awaiting trial on charges related to allegations made by Duterte in August 2016.[113] A court date has not been set.[114]

Arturo Lascañas

On February 20, Arturo Lascañas, a retired police officer, told reporters at a press conference outside the senate building that as a leader of the Davao Death Squad he had carried out extrajudicial killings on the orders of Duterte. He said death squad members were paid 20,000 to 100,000 pesos ($400 to $2,000) per hit, depending on the importance of the target. He gave details of various killings he had carried out on Duterte's orders, including the previously unsolved murder of a radio show host critical of Duterte, and confessed to his involvement with Matobato in the bombing of a mosque on Duterte's orders.[115][116] On the following day the senate voted in a private session to reopen the investigation, reportedly by a margin of ten votes to eight, with five abstentions.[117]

On March 6, Lascanas gave evidence at the Senate committee, testifying that he had killed approximately 200 criminal suspects, media figures and political opponents on Duterte's orders.[118]

Allegations of police using hospitals to hide killings

In June 2017 Reuters reported that "Police were sending corpses to hospitals to destroy evidence at crime scenes and hide the fact that they were executing drug suspects." Doctors stated that corpses loaded onto trucks were being dumped at hospitals, sometimes after rigor mortis had already set in, with clearly unsurvivable wounds, having been shot in the chest and head at close range. Reuters examined data from two Manila police districts, and found that the proportion of suspects sent to hospitals, where they are pronounced dead on arrival (DOA), increased from 13% in July 2016 to 85% in January 2017; "The totals grew along with international and domestic condemnation of Duterte's campaign."[119]

Ozamiz raid, and death of Reynaldo Parojinog

On July 30, Reynaldo Parojinog, the mayor of Ozamiz City, was killed along with 14 others, including his wife Susan, in a dawn raid at around 2:30 am on his home in San Roque Lawis.[120][121] According to police, they were on a search warrant when Parojinog's bodyguards opened fire on them and police officers responded by shooting at them. According to police provincial chief Jaysen De Guzman, authorities recovered grenades, ammunition and illegal drugs in the raid.[122][123]

"One-time, big-time" operations

On August 16, over 32 people were killed in multiple "one-time, big-time" antidrug operations in Bulacan within one day.[124] On Manila, 25 people, including 11 suspected robbers, were also killed in consecutive anti-criminality operations.[125] The multiple deaths in the large-scale antidrug operations received condemnation from human rights groups and the majority of the Senate.[126][127]

Youth casualties

On August 17, Kian Loyd delos Santos, a 17-year-old Grade 11 student, was shot dead in an antidrug operation in Caloocan.[128][129] CCTV footage appeared to show Kian being dragged by two policemen. Police say they killed him in self-defense, and retrieved a gun and two packets of methamphetamine.[128] Delos Santos was the son of an overseas Filipino worker, a key demographic in support of Duterte.[130] The teenager's death caused condemnation by senators.[131][132] His funeral on August 25, attended by more than a thousand people, was one of the largest protests to date against the Drug War.[133]

Carl Angelo Arnaiz, a 19-year-old teenager, last found in Cainta, Rizal, was tortured and shot dead also on August 17 (the same date Kian delos Santos was killed) by police after robbing a taxi in Caloocan.[134] His 14-year-old friend, Reynaldo de Guzman, also called under the nickname "Kulot", was stabbed to death thirty times and thrown into a creek in Gapan, Nueva Ecija. Along with the deaths of Kian delos Santos, the deaths of the two teenagers also triggered public outrage and condemnation.[135]

Human Rights Watch repeated their call for a UN investigation. HRW Asia director Phelim Kine commented: "The apparent willingness of Philippine police to deliberately target children for execution marks an appalling new level of depravity in this so-called drug war".[136] Duterte called the deaths of Arnaiz and de Guzman (the former being a relative of the President on his mother's side) a "sabotage", believing that some groups are using the Philippine National Police to destroy the president's public image.[137] Presidential spokesman Abella said "It should not come as a surprise that these malignant elements would conspire to sabotage the president’s campaign to rid the Philippines of illegal drugs and criminality", which "may include creating scenarios stoking public anger against the government".[136]

On August 23, 2016, a 5-year-old student named Danica May Garcia was killed by a stray bullet coming from the unidentified gunmen in Dagupan City, Pangasinan during an anti-drug operation.[138] Another minor, 4-year old Skyler Abatayo of Cebu was killed by a stray bullet through an 'anti-drug operation'.[139] In the first year of the Drug War, 54 children were recorded as casualties.[31]

Reshuffling of the Caloocan City Police

As a result of involvement in the deaths of teenagers like Kian delos Santos, and Carl Angelo Arnaiz and Reynaldo de Guzman, and robbing of a drug suspect in an antidrug raid, National Capital Region Police Office (NCRPO) chief Oscar Albayalde ordered the firing and retraining of all members of the Caloocan City Police, with the exception of its newly appointed chief and its deputy.[140]

Transfer of anti-drug operations to PDEA

On October 12, 2017, Duterte announced the transfer of anti-drug operations to the Philippine Drug Enforcement Agency (PDEA), ending the involvement of the Philippine National Police (PNP). The announcement followed the publication of an opinion poll on October 8, showing a drop in presidential approval from 66% to 48%.[141][142] In a televised speech, Duterte scoffed and mocked the "bleeding hearts" who sympathized with those killed in the drug war, pointedly at the European Union, whom he accused of interfering with Philippine sovereignty.[143]

Rodrigo Duterte's refutation to ASEAN representatives

In a speech before ASEAN representatives, Rodrigo Duterte refuted all extrajudicial killings related to the War on Drugs by stating that these stories only serve as a political agenda in order to demonize him. He stated that he has only used his mouth to tell drug users that they will be killed. He stated that "..."shabu" (crystal meth) users have shrunken brains, which is why they have become violent and aggressive, leading to their deaths."[144] Duterte further added that all the drug pushers and their henchmen always carry their guns with them and killing them is justifiable so that they would not endanger the lives of his men.[145] Duterte appointed a human rights lawyer, Harry Roque, a Kabayan partylist representative, as his spokesperson. Roque stated that he will change public perception by reducing the impact of the statements by which Duterte advocates extra-judicial killings in his war on drugs.[146]

2018

In a speech on March 26, 2018, Duterte said that human rights groups "have become unwitting tools of drug lords". Human Rights Watch denied the allegation, calling it "shockingly dangerous and shameful".[147]

Consecutive assassinations of local government officials

The controversial Tanauan, Batangas mayor Antonio Halili was assassinated by an unknown sniper during a flag-raising ceremony on July 2, 2018, becoming the 11th local government official to be killed in the Drug War. On the following day, Ferdinand Bote, mayor of General Tinio, was shot dead in his vehicle in Cabanatuan City.[148][149]

2019

On January 17, 2019, Sri Lankan President Maithripala Sirisena, on his state visit in the country, praised the war on drugs campaign, saying that the campaign is "an example to the whole world."[150] Two days later, human rights groups had expressed alarm over the statement of Sirisena.[151] On January 18, the Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project (ACLED) issued a statement, saying that the Philippines along with Syria, Nigeria, Yemen, and Afghanistan, is "one of the deadliest places in the world to be a civilian", citing deaths in the drug war. Malacanang reacted by saying that the report "is remarkable in ignorance and bias."[152] A survey conducted by SWS from December 16-19, 2018 showing that 66% of the Filipinos believe that drug addicts in the country have diminished substantially.[153] However, on February 19, 2019, opposition Senator Antonio Trillanes made a statement about the few drug addicts, whom Trillanes said that "they were killed 'without due process,'" and slams Presidential Spokesperson Salvador Panelo by saying "what are you celebrating, Mr. Panelo, the ruthlessness of your boss?"[154]

On March 1, 2019, results of an SWS survey conducted from December 16 to 19, 2018 on 1,440 adults nationwide was released which concluded that 78% (or almost 4 out of 5 Filipinos) are worried "that they, or someone they know, will be a victim of extrajudicial killings (EJK)."[155] However, Philippine National Police chief, Police General Oscar Albayalde criticized the survey results pointing out that the survey wrongly presented a question which "cannot be validated by respondents without keen awareness or understanding of EJK as we know it from Administrative Order No. 35 Series of 2012 by President [Benigno Simeon] Aquino [III]." He reiterated "I take the latest survey results on public perception to alleged extrajudicial killing with a full cup of salt. It shouldn’t be surprising that 78 percent are afraid of getting killed. Who isn’t afraid to die, anyway?"[156]

On March 14, Duterte released another list of the politicians allegedly involved in the illegal drug trade. The list consists of 45 incumbent officials: 33 mayors, 8 vice mayors, 3 congressmen, one board member, and one former mayor.[157] Of all politicians named, there are eight politicians belong to Duterte's own political party PDP–Laban.[158] Opposition figures such as senatorial candidates from Otso Diretso said that Duterte used the list "to ensure their allies would win" in May 2019 election.[159]

On March 17, the country formally withdrawn from the ICC after the country's withdrawal notification was received by the Secretary-General of the United Nations last year.[160]

International Criminal Court

The International Criminal Court (ICC) chief prosecutor Fatou Bensouda expressed concern, over the drug-related killings in the country, on October 13, 2016.[161] In her statement, Bensouda said that the high officials of the country "seem to condone such killings and further seem to encourage State forces and civilians alike to continue targeting these individuals with lethal force."[162] She also warns that any person in the country who provoke "in acts of mass violence by ordering, requesting, encouraging or contributing, in any other manner, to the commission of crimes within the jurisdiction of ICC" will be prosecuted before the court.[163] About that, Duterte is open for the investigation by the ICC, Malacañang said.[163]

In February 2018, the ICC announced a “preliminary examination” into killings linked to the Philippine government's “war on drugs”. Prosecutor Bensouda said the court will “analyze crimes allegedly committed in [the Philippines] since at least 1 July 2016.” Duterte's spokesman Harry Roque dismissed the ICC's decision as a “waste of the court’s time and resources”.[164][165][166] In March, Duterte announced his intention to withdraw the Philippines from the ICC tribunal, which is a process that takes a year.[167][147]

In August 2018, activists and eight families of victims of the Drug War filed a second petition with the ICC, accusing Duterte of murder and crimes against humanity, and calling for his indictment for thousands of extrajudicial killings, which according to the 50-page complaint included "brazen" executions by police acting with impunity. Neri Colmenares, a lawyer acting for the group, said that "Duterte is personally liable for ordering state police to undertake mass killings". Duterte threatened to arrest the ICC prosecutor Bensouda.[168]

Reactions

Local

Senator Risa Hontiveros, an opponent of Duterte, said that the Drug War was a political strategy intended to persuade people that "suddenly the historically most important issue of poverty was no longer the most important."[45] De Lima expressed frustration with the attitude of Filipinos towards extrajudicial killing: "they think that it's good for peace and order. We now have death squads on a national scale, but I'm not seeing public outrage."[45] According to a Pulse Asia opinion poll conducted from July 2 to 8, 2016, 91% of Filipinos "trusted" Duterte.[169] A survey conducted between February and May 2017, by PEW research center, found that 78% of the Filipinos support the drug war.[170] A survey in September 2017 showed 88% support for the Drug War, while 73% believed that extrajudicial executions were occurring.[27]

Dela Rosa announced in September 2016 that the Drug War had "reduced the supply of illegal drugs in the country by some 80 to 90 percent",[171] and said that the War was already being won, based on statistical and observational evidence.[172]Aljazeera reported that John Collins, director of the London School of Economics International Drug Policy Project, said: "Targeting the supply side can have short-term effects. However, these are usually limited to creating market chaos rather than reducing the size of the market. ... What you learn is that you're going to war with a force of economics and the force of economics tends to win out: supply, demand and price tend to find their own way." He said it was a "certainty" that "the Philippines' new 'war' will fail and society will emerge worse off from it."[45] In June 2017 the price of methamphetamine on the streets of Manila was lower than it had been at the start of Duterte's presidency, according to Philippine Drug Enforcement Agency data. Gloria Lai of the International Drug Policy Consortium commented: "If prices have fallen, it's an indication that enforcement actions have not been effective".[173]

The Chairman of the Philippine Chamber of Commerce and Industry, Sergio Ortiz-Luis Jr., quelled fears that foreign investors might be put off by the increasing rate of killings in the country, explaining at a press conference on September 19, 2016, that investors only care about profit: "They don't care if 50 percent of Filipinos are killing each other so long as they're not affected".[174] On the following day the Wall Street Journal reported that foreign investors, who account for half of the activity on the Philippine Stock Exchange, had been "hightailing it out of town", selling $500 million worth of shares over the past month, putting pressure on the Philippine peso which was close to its weakest point since 2009.[175]

The Archbishop of Manila Luis Antonio Tagle acknowledged that people were right to be "worried about extrajudicial killings", along with other "form[s] of murder": abortion, unfair labor practices, wasting food, and "selling illegal drugs, pushing the youth to go into vices".[176]

International

Protest against the Philippine war on drugs in front of the Philippine Consulate General in New York City. The protesters are holding placards which urge Duterte to stop killing drug users.

During his official state visit to the Philippines in January 2017, Japanese Prime Minister Shinzō Abe said: "On countering illegal drugs, we want to work together with the Philippines through relevant measures of support". He offered financial assistance for Philippine drug rehabilitation centres, and made no mention of deaths resulting from the drug war. He announced a $800 million Official Development Assistance package to "promote economic and infrastructure development".[177]

Gary Song-Huann Lin, the representative of Taiwan in the Philippines, welcomed Duterte's plan to declare a war against criminality and illegal drugs. He said Taiwan is ready to help the Philippines combat cross-border crimes like human and drug trafficking.[178]

On July 19, 2016, Lingxiao Li, spokesman for the Chinese Embassy in Manila, announced China's support for the Drug War: "China fully understands that the Philippine government under the leadership of H. E. President Rodrigo Duterte has taken it as a top priority to crack down drug-related crimes. China has expressed explicitly to the new administration China's willingness for effective cooperation in this regard, and would like to work out a specific plan of action with the Philippine side." The statement made no reference to extrajudicial killings, and called illegal drugs the "common enemy of mankind".[179][180][181] On September 27, the Chinese Ambassador Zhao Jianhua reiterated that "Illegal drugs are the enemy of all mankind" in a statement confirming Chinese support for the Duterte administration.[180]

Indonesian National Police Chief General Tito Karnavian commented in regards to Indonesia's rejection of a similar policy for Indonesia: "Shoot on sight policy leads to abuse of power. We still believe in the presumption of innocence. Lethal actions are only warranted if there is an immediate threat against officers... there should not be a deliberate attempt to kill".[182] In September 2016 Budi Waseso, head of Indonesia's National Anti-Narcotics Agency (BNN), said that he was currently contemplating copying the Philippines' hardline tactics against drug traffickers. He said that the Agency planned a major increase in armaments and recruitment. An Agency spokesman later attempted to downplay the comments, stating: "We can't shoot criminals just like that, we have to follow the rules."[183] Most recently, Indonesian President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo used the language of “emergency” to ramp up the country's war on drugs, in a move that observers see as "in step with Filipino President Rodrigo Duterte’s" own campaign against the illegal drug trade.[184]

On October 16, prior to Duterte's departure for a state visit to Brunei, the President said he would seek the support of that country for his campaign against illegal drugs and Brunei's continued assistance to achieve peace and progress in Mindanao.[185] This was responded positively from Brunei Sultan Hassanal Bolkiah in the next day according to Philippine Foreign Affairs Secretary Perfecto Yasay Jr.[186]Malaysia's Deputy Prime Minister Ahmad Zahid Hamidi said "he respect the method undertaken by the Philippine government as it is suitable for their country situation", while stressing that "Malaysia will never follow such example as we have our own methods with one of those such as seizing assets used in drug trafficking with resultant funds to be channelled back towards rehabilitation, prevention and enforcement of laws against drugs".[187]

On December 3, 2016, Duterte said that during a phone conversation on the previous day with then-United States President-elect Donald Trump, Trump had invited him to Washington, and endorsed his Drug War policy, assuring him that it was being conducted "the right way".[188] Duterte described the conversation:

I could sense a good rapport, an animated President-elect Trump. And he was wishing me success in my campaign against the drug problem. [...] He understood the way we are handling it, and I said that there’s nothing wrong in protecting a country. It was a bit very encouraging in the sense that I supposed that what he really wanted to say was that we would be the last to interfere in the affairs of your own country.[189]

On December 16, Duterte and Singaporean President Tony Tan and Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong agreed to work together in the fight against terrorism and illegal drugs. In a meeting during a state visit both parties discussed areas of cooperation between the two countries.[190]

The European Parliament expressed concern over the extrajudicial killings after a resolution on September 15, stating: "Drug trafficking and drug abuse in the Philippines remain a serious national and international concern, note MEPs. They understand that millions of people are hurt by the high level of drug addiction and its consequences in the country but are also concerned by the 'extraordinarily high numbers killed during police operations in the context of an intensified anti-crime and anti-drug campaign."[191] In response, at a press conference Duterte made an obscene hand gesture and called British and French representatives "hypocrites" because their ancestors had killed thousands of Arabs and others in the colonial era. He said: "When I read the EU condemnation I told them fuck you. You are doing it in atonement for your sins. They are now strict because they have guilty feelings. Who did I kill? Assuming that it's true? 1,700? How many have they killed?"[192][193]

EU Trade Commissioner Cecilia Malmström, in a visit to the Philippines in March 2017, warned that unless the Philippines addresses human rights issues, the EU would cancel tariff-free export of 6,000 products under the Generalized System of Preferences. Presidential spokesman Ernesto Abella dismissed the concerns, saying that they revealed European ignorance.[177]

On December 24, U.S. Senators Marco Rubio, Edward Markey, and Christopher Coons expressed their concerns regarding the alleged extrajudicial killings and human rights violations in Duterte's war on drugs. Through a letter sent to the U.S. Department of State, they noted that instead of addressing the drug problem, investing in treatment programs or approaching the issue with an emphasis on health, Duterte has "pledged to kill another 20,000 to 30,000 people, many simply because they suffer from a drug use disorder." Rubio, Markey and Coons also questioned U.S. secretary of state John Kerry's pledge of $32-million funding for training and other law-enforcement assistance during his visit to Manila.[194][195] In May 2017, Senator Rubio, along with Senator Ben Cardin, filed a bipartisan bill in the U.S. Senate to restrict the exportation of weapons from the U.S. to the Philippines.[196]

The US ambassador in Manila announced on December 14, 2016, that the US foreign aid agency, the Millennium Challenge Corporation, would cancel funding to the Philippines due to "significant concerns around rule of law and civil liberties in the Philippines", explaining that aid recipients were required to demonstrate a "commitment to the rule of law, due process and respect for human rights". The MCC had disbursed $434 million to the Philippines from 2011 to 2015. The funding denial was expected to lead to the cancellation of a five-year infrastructure development project previously agreed to in December 2015.[177]

In February 2017, former Colombian President César Gaviria wrote an opinion piece on The New York Times to warn Duterte and the administration that the drug war is "unwinnable" and "disastrous", citing his own experiences as the President of Colombia. He also criticized the alleged extrajudicial killings and vigilantism, saying these are "the wrong ways to go". According to Gaviria, the war on drugs is essentially a war on people.[197] Gaviria suggested that improving public health and safety, strengthening anti-corruption measures, investing in sustainable development, decriminalizing drug consumption, and strengthening the regulation of therapeutic goods would enhance supply and demand reduction. In response to Gaviria, Duterte called him an "idiot", and said the issue of extrajudicial killings should be set aside, and that there were four to five million drug addicts in the country.[198][199]

In September 2017, Foreign Affairs Secretary Alan Peter Cayetano delivered a speech at the 72nd United Nations General Assembly, during which he argued that extrajudicial killings were a myth, and that the Drug war, which according to Human Rights Watch has resulted in 13,000 deaths to date, was being waged to "protect (the) human rights of...the most vulnerable (citizens)".[200]

In October 2017, Secretary Cayetano was interviewed by the Qatari news outlet al-Jazeera. He asserted that all 3,900 people who were killed in the drug war fought against the police despite there having been no investigations conducted prior to the drug busts. He also rebuffed all claims that the drug war was against its people.[201]

38-nation statement against the drug war

On June 19, 2018, 38 United Nations member states released a collective statement through the United Nations Human Rights Council (UNHRC), calling on the Republic of the Philippines and Philippine president Rodrigo Duterte to stop the killings in the country and probe abuses caused by the deadly drug war. The 38 nations included Australia, Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Canada, Croatia, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Georgia, Germany, Greece, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Liechtenstein, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, Macedonia, Montenegro, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Ukraine, the United Kingdom and the United States.[202][203][204]

In popular media

Television

On April 9, 2018, Netflix aired its first series from the Philippines entitled, AMO, made by Filipino director, Brillante Mendoza.[205]

Music

"Hustisya" is a rap song about the drug war which was created by local artists inspired by the death of their friend immortalized in a photograph often compared to Michelangelo's Pieta.[206]

In December 2016, American singer James Taylor posted on social media that he had cancelled his concert in Manila, which was set for February 2017, citing the increasing number of deaths related to the drug war.[207][208]

Photography

On April 11, 2017, The New York Times won a Pulitzer Prize for breaking news photography on their Philippine Drug war report. The story was published on December 7, 2016, and was titled "They Are Slaughtering Us Like Animals".[209]

The La Pieta[210] or the "Philippines Pieta", named after the sculpture by Michelangelo, refers to the photograph of Jennilyn Olayres holding the lifeless corpse of Michael Siaron, who was shot dead by unidentified assailants in Pasay, Metro Manila, on July 23, 2016. The image was widely used in the national press.[211] The death of Michael Siaron remains unsolved for almost a year. Malacañang asserts that the man behind the killing were committed by drug syndicates themselves.[212] After Siaron was shot dead by unidentified assailants, a writing on a cardboard states, "Wag tularan si Siaron dahil pusher umano," was placed on his body.[212] One year and three months after he was killed, the police identified the suspected assailant as Nesty Santiago through a ballistic exam on the recovered firearm.[213] Santiago was apparently a member of a syndicate involved in robberies, car thefts, hired killings and illegal drugs. The Pasay City Police declared his death as "case closed". However, Santiago was also killed by riding-in-tandem on December 29, 2016.[213] No further investigation were made.[213]

A photo of a body of an alleged drug dealer, killed during a police anti-drug operation, in Manila by Noel Celis has been selected as one of Time Magazine's top 100 photos of 2017.[214]

Mobile gaming

There are various mobile games featuring Duterte fighting criminals,[215] many of which have since been censored by Apple Inc. from their App Store following an appeal by various regional organizations.[216]

See also

- Bangladesh Drug War

- Mexican Drug War

- Thailand Drug War

- 2017 Bureau of Customs drug smuggling scandal

- Comprehensive Dangerous Drugs Act of 2002

- Illegal drug trade in the Philippines

- Mega Drug Treatment and Rehabilitation Center

- War on Drugs

Notes

^ The Communist Party of the Philippines (CPP) and its armed wing the New People's Army (NPA), initially cooperated with the government but withdrew its support for the government's campaign against drug in August 2016. The CPP has vowed continued operations, independent from the government's anti-drug campaign, against drug suspects by the NPA.[3]

^ Foreign support towards the campaign against illegal drugs including intelligence sharing, training of Filipino law enforcement officers, and financial aid explicitly meant for such purposes. Excludes governments which has only expressed verbal, diplomatic support, and pledges that has yet to be realized

References

^ France-Presse, Agence (6 December 2017). "Philippines: Rodrigo Duterte orders police back into deadly drug war". the Guardian..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ "NPA backs Duterte fight vs drugs". ABS-CBN News. 4 July 2016. Retrieved 6 March 2019.

^ News, ABS-CBN. "CPP: Duterte's drug war is 'anti-people, anti-democratic'".Communist Party of the Philippines (CPP) has withdrawn its support for President Rodrigo Duterte's war on illegal drugs, saying it has "clearly become anti-people and anti-democratic.""; "In conclusion, the group said its armed wing, the New People's Army (NPA), will intensify its operations to arrest and disarm drug suspects, but will no longer cooperate with government's anti-narcotics drive.

^ Lim, Frinston (July 3, 2017). "MILF formally joins war on drugs". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Retrieved July 4, 2017.

^ Kabiling, Genalyn (August 5, 2017). "MNLF to help Gov't fight drugs, terrorism".

^ Woody, Christopher (September 5, 2016). "The Philippines' president has declared a war on drugs, and it's turned normal people into hired killers". Business Insider. Retrieved September 22, 2016.

^ abc "Philippines: The police's murderous war on the poor". Amnesty International. Retrieved February 9, 2017.

^ Nyshka Chandran (14 November 2017). "The US-Philippine relationship is central to two of Asia's thorniest issues". CNBC. Retrieved 10 July 2018.

^ abc Richard Heydarian (1 October 2017). "Manila's war on drugs is helping to build bridges between China and the Philippines". South China Morning Post. Retrieved 10 July 2018.

^ Aben, Elena L. (17 December 2016). "Singapore backs Duterte's tough stance against drugs". Manila Bulletin News. Archived from the original on 1 December 2018. Retrieved 4 March 2019.

^ Mirasol, Jeremy Dexter (May 2017). "Cooperation with China on the Philippines' War on Drugs". Center for International Relations and Strategic Studies (CIRSS). Retrieved 6 March 2019.

^ "18 killed overnight in Manila". 17 August 2017. Retrieved 6 March 2019.

^ "Lawless group member drug suspect nabbed in Lanao del norte Sultan Kudarat". 4 March 2018. Retrieved 27 February 2019.

^ "Sinaloa cartel in cahoots with Chinese syndicates for Philippine ops - PDEA". 13 February 2019. Retrieved 13 February 2019.

^ "PDEA names triads behind shabu supply in Philippines". October 3, 2017. Retrieved 13 February 2019.

^ "Colombian drug cartel active in PH, PDEA says". February 27, 2019. Retrieved February 27, 2019.

^ Philippine Information Agency #RealNumbersPH

^ "5 PDEA agents killed in Lanao del Sur ambush". Rapler. Retrieved 2018-10-10.

^ "Albayalde offers security for priests receiving death threats". Manila Bulletin.

^ abcd "Police to change strategy in anti-drug war based on Duterte's estimate of drug users". 28 February 2018. Archived from the original on 5 March 2018. Retrieved 31 March 2019.

^ abcd Merez, Arianne (28 February 2019). "5,000 killed and 170,000 arrested in war on drugs: police". ABS-CBN News. Archived from the original on 29 March 2019. Retrieved 31 March 2019.

^ Tubeza, Philip C. (28 February 2017). "Bato: 'Neutralization' means arrest". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Archived from the original on 27 February 2019. Retrieved 4 March 2019.

^ abc "Philippines president Rodrigo Duterte urged people to kill drug addicts". Associated Press. 1 July 2016. Retrieved 8 July 2016 – via The Guardian.

^ "Duterte Vows More Bloodshed in Philippine 'Drug War'". Human Rights Watch. Retrieved 5 October 2018.

^ "Special Report: Police describe kill rewards, staged crime scenes in Duterte's drug war". Reuters. April 18, 2017. Retrieved October 21, 2018.

^ "Japan Prime Minister Shinzo Abe offers Philippines drug war support". The Straits Times. January 12, 2017. Retrieved March 8, 2019.

^ ab "Philippine survey shows big support for Duterte's drugs war". Reuters. October 16, 2017. Retrieved October 13, 2018.

^ "Trump's call for death penalty is the wrong response to drug war". The Hill. February 3, 2018. Retrieved October 13, 2018.

^ http://cnnphilippines.com/news/2019/02/16/SWS-Filipinos-drug-addicts-decrease-2018.html

^ ab "PNP bares numbers: 4,251 dead in drug war". The Philippine Star. May 8, 2018. Archived from the original on 2018-06-12.

^ abc "The Guardian view on the Philippines: a murderous 'war on drugs'". The Guardian. September 28, 2018. Retrieved September 29, 2018.

^ "Trillanes calls on Senate to defend De Lima, press freedom, right to life". Rappler.

^ "Critics hit Duterte's promise to continue campaign against drugs". UNTV News and Rescue. Retrieved July 25, 2018.

^ "Philippine death squads very much in business as Duterte set for presidency". Reuters. 26 May 2016. Retrieved 14 September 2016.Human rights groups have documented at least 1,400 killings in Davao that they allege had been carried out by death squads since 1998. Most of those killed were drug users, petty criminals and street children.

^ "Rodrigo Duterte: The Rise of Philippines' Death Squad Mayor". The Mark News. 17 July 2015. Archived from the original on 2016-09-01.

^ Zabriskie, Phil (19 July 2002). "The Punisher". Time. Archived from the original on 22 October 2010.

^ "Philippines senator who branded President Duterte 'serial killer' arrested". The Guardian. 23 February 2017. Retrieved 24 February 2017.

^ "Duterte calls for press conference Monday afternoon". CNN Philippines. 12 October 2015. Retrieved 11 October 2017.

^ "Rodrigo Duterte: The Rise of Philippines' Death Squad Mayor". Human Rights Watch. 17 July 2015. Archived from the original on 1 September 2016. Retrieved 1 October 2017.

^ "The Philippines' strongman president is losing popularity as citizens tire of drug war". CNBC. 11 October 2017. Retrieved 11 October 2017.

^ "Thousands dead: the Philippine president, the death squad allegations and a brutal drugs war". The Guardian. 2 April 2017. Retrieved 28 September 2017.

^ "Philippine death squads very much in business as Duterte set for presidency". Reuters. May 26, 2016. Retrieved September 14, 2016.

^ ab "Suspect Stats". Reuters. 18 October 2016. Retrieved 8 February 2017.

^ "Philippines: Duterte's 100 days of carnage". Amnesty International. Retrieved 8 October 2016.

^ abcd "Philippines: Inside Duterte's killer drug war". Al Jazeera. 8 September 2016. Retrieved 2 October 2016.

^ "'Go ahead and kill drug addicts': Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte issues fresh call for vigilante violence". South China Morning Post. July 2, 2016. Retrieved October 18, 2018.

^ "Communists answer Duterte's call to join fight vs. drugs". Retrieved July 9, 2016.

^ "Bayan to maintain presence in the streets despite Duterte alliance". Retrieved July 9, 2016.

^ "Philippine police kill 10 in Duterte's war on crime". Retrieved July 9, 2016.

^ "Thirty killed in four days in Philippine war on drugs". July 4, 2016. Retrieved July 9, 2016 – via Reuters.

^ ab "Palace to critics of war vs drugs: Show proof of violations". Rappler. Retrieved July 9, 2016.

^ "Drug war 'spiraling out of control'". Philippine Daily Inquirer. July 9, 2016.

^ "MILF ready to aid Duterte in war vs drugs". Sun Star Cebu. Retrieved July 9, 2016.

^ ab "Du30 blasts triad, drug cartel". The Manila Standard. August 4, 2016.

^ "FULL TEXT: Duterte reveals gov't officials involved in drugs". Philippine Daily Inquirer (in English and Tagalog). 7 August 2016. Archived from the original on 4 March 2019. Retrieved 4 March 2019.

^ "Duterte names government officials, judiciary, PNP personnel allegedly linked to illegal drug trade". CNN Philippines. 7 August 2016. Retrieved 4 March 2019.

^ "Rody names politicians, judges, cops allegedly in illegal drugs". Philippine Daily Inquirer. August 7, 2016. Retrieved August 7, 2016.

^ "US 'concerned' by EJKs in war on drugs". Agence France-Presse. Interaksyon. August 9, 2016. Archived from the original on August 9, 2016. Retrieved August 10, 2016.

^ Señase, Charlie C. (August 18, 2016). "Duterte tells De Lima: I have witnesses against you". Inquirer Mindanao, Philippine Daily Inquirer. Inquirer.net. Archived from the original on August 18, 2016. Retrieved 22 August 2016.

^ "'Love affair led to corruption'" (August 21, 2016). LLANESCA PANTI. The Manila Times. Retrieved 22 August 2016.

^ "UN rights experts urge Philippines to end wave of extrajudicial killings amid major drug crackdown". UN News Centre. United Nations. August 18, 2016. Retrieved 22 August 2016.

^ "UN experts urge the Philippines to stop unlawful killings of people suspected of drug-related offences". United Nations Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner. United Nations. August 18, 2016. Retrieved 22 August 2016.

^ Fabunan and, Sara Susanne D.; Bencito, John Paolo (23 August 2016). "PH not leaving UN after all". Manila Standard. Archived from the original on 4 March 2019. Retrieved 4 March 2019.

^ "Philippines Drug-War Deaths Double as President Duterte Lashes Out at U.N." NBC News. 22 August 2016.

^ "CHR: ICC may exercise jurisdiction over PH drug killings if …". Philippine Daily Inquirer. August 23, 2016.

^ "Duterte matrix out; tags De Lima, ex-Pangasinan gov, others". August 25, 2016. Retrieved August 25, 2016.

^ "Duterte's drug matrix". CNN Philippines. August 25, 2016. Retrieved August 25, 2016.

^ "De Lima laughs off Duterte's 'drug matrix'". GMA News. August 25, 2016. Retrieved August 25, 2016.

^ Corrales, Nestor. "Duterte tells De Lima: Resign, hang yourself". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Archived from the original on 5 September 2018. Retrieved 4 March 2019.

^ Solomon, F. (September 6, 2016). "Rodrigo Duterte declares a state of emergency in the Philippines". Time. Retrieved September 6, 2016.

^ Viray, Patricia Lourdes. "Palace issues proclamation of state of national emergency". The Philippine Star. Archived from the original on 6 September 2016. Retrieved 4 March 2019.

^ Viray, P.L. (September 6, 2016). "Palace issues proclamation of state of national emergency". The Philippine Star. Retrieved September 6, 2016.

^ "Duterte's First 100 Days". Huffington Post. October 7, 2016. Retrieved October 9, 2016.

^ "Obama cancels meeting with 'colorful' Philippine president, who now expresses regret…". The Washington Post. September 5, 2016.

^ "After cursing Obama, Duterte expresses regret…". CNN. September 5, 2016.

^ Hernandez, Zen (19 September 2016). "Pacquiao moves to unseat de Lima as committee chair". ABS-CBN News. Retrieved 4 March 2019.

^ "The Philippine President's Dwindling Opposition". The Atlantic. September 19, 2016. Retrieved September 26, 2016.

^ "Philippine hitman says he heard Duterte order killings". Reuters. September 15, 2016. Retrieved October 4, 2017.

^ "Philippine president Rodrigo Duterte to extend drug war as 'cannot kill them all'". The Guardian. September 19, 2016.

^ "Rodrigo Duterte: Philippines president to extend war on drugs because he 'can't kill them all'". The Independent. September 20, 2016. Retrieved September 28, 2016.

^ "Duterte critic took bribes, Philippine felons tell Congress members". Reuters. September 20, 2016. Retrieved September 22, 2016.

^ Symmes, Patrick (10 January 2017). "President Duterte's List". The New York Times. Retrieved 4 March 2019.

^ "Ronald dela Rosa: 'The Rock' behind Duterte's drugs war". BBC. June 27, 2018. Retrieved October 19, 2018.

^ ab Holmes, Oliver (1 October 2016). "Rodrigo Duterte vows to kill 3 million drug addicts and likens himself to Hitler". The Guardian. Retrieved 4 March 2019.

^ "Rodrigo Duterte's Hitler remarks 'deeply troubling': Pentagon chief". The Straits Times. 1 October 2016. Retrieved 4 March 2019.

^ "Duterte's Hitler remarks 'deeply troubling,' says Pentagon chief". Philippine Daily Inquirer.

^ "Germany: Duterte Hitler remarks 'unacceptable'". Philippine Daily Inquirer.

^ "Duterte apologizes to Jews for Hitler remarks". GMA News.

^ "Duterte apologizes to Jews for Hitler remark". The Philippine Star.

^ "Philippines secret death squads: officer claims police teams behind wave of killings". The Guardian. Retrieved October 6, 2016.

^ "End of the road for mayor on drug list, 9 others". Philippine Daily Inquirer.

^ "Maguindanao mayor, 9 others dead in clash with anti-drug police". Philippine Daily Inquirer.

^ "8 Maguindanao officials linked to drugs surrender to PNP chief". Philippine Daily Inquirer.

^ Philippines' Duterte: We'll turn to Russia if US won't sell us guns, CNN. November 2, 2016.

^ Exclusive: U.S. stopped Philippines rifle sale that senator opposed - sources, Reuters. November 1, 2016.

^ "Duterte cancels order of 26,000 rifles from US". Inquirer. November 7, 2016. Retrieved November 8, 2016.

^ "Leyte Mayor Rolando Espinosa killed in 'firefight' inside jail". Philippine Daily Inquirer. 5 November 2016. Retrieved 4 March 2019.

^ "'NANLABAN'? - With video: Albuera Mayor Espinosa killed in Leyte jail". InterAksyon.

^ "CCTV footage of Albuera mayor's death missing". ABS-CBN News.

^ "DUTERTE'S LIST: 'Narco' politicos, lawmen, judges". ABS-CBN News.

^ "Albuera Mayor Espinosa, 1 other inmate killed in jail cell shootout – CIDG". CNN Philippines.

^ "Mayor accused over drugs killed in Philippines jail, say police". The Independent. November 5, 2016. Retrieved November 7, 2016.

^ "Espinosa killing 'incredibly brazen' - rights lawyer". InterAksyon. November 5, 2016. Retrieved November 7, 2016.

^ "Lacson to seek resumption of Senate EJK probe after Espinosa's killing". GMA News.

^ "Senate hearings on killings 'suspended until further notice'". GMA News.

^ "Duterte threat to kill rights defenders alarms groups". ABSCBN. AFP. November 30, 2016. Retrieved December 3, 2016.

^ "Police rack up an almost perfectly deadly record in Philippine drug war". Reuters. December 5, 2016. Retrieved 20 September 2017.

^ "WATCH | Gordon panel: No proof of EJK, DDS in war on drugs under Duterte". December 8, 2016. Retrieved December 8, 2016.

^ ab "PHILIPPINES: "IF YOU ARE POOR, YOU ARE KILLED": EXTRAJUDICIAL KILLINGS IN THE PHILIPPINES' "WAR ON DRUGS"". Amnesty International. Retrieved 12 February 2017.

^ "Philippines police behave like 'criminal underworld' in drugs war - Amnesty". Reuters. February 1, 2017. Retrieved February 8, 2017.

^ "Philippines police paid to kill alleged drug offenders, says Amnesty". The Guardian. January 31, 2017. Retrieved February 13, 2017.

^ "'Amnesty lnternational naive and stupid'". Philstar. February 6, 2017. Retrieved February 24, 2017.

^ "Philippines: Duterte critic De Lima arrested on drug-related charges". CNN. March 1, 2017. Retrieved 29 September 2017.

^ "Jailed Philippine Senator: 'I Won't Be Silenced Or Cowed'". NPR. June 24, 2017. Retrieved 29 September 2017.

^ "Retired Philippine policeman says Duterte ordered 'death squad' hits". Reuters. February 20, 2017. Retrieved October 4, 2017.

^ "Retired SPO3 Lascanas: What he said before, what he now says". ABS CBN. February 20, 2017. Retrieved October 4, 2017.

^ Ager, Maila (22 February 2017). "10 senators vote to proceed with probe on Duterte's DDS 'ties'". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Retrieved 4 March 2019.

^ "Self-proclaimed death squad chief: I killed almost 200 for Duterte". CNN. March 6, 2017. Retrieved October 6, 2017.

^ "Philippine police use hospitals to hide drug war killings". Reuters. June 29, 2017. Retrieved 23 September 2017.

^ "Ozamiz City Mayor, 14 others killed in exchange of gunfire with police". CNN Philippines. Retrieved July 30, 2017.

^ Nawal, Allan. "Mayor Parojinog killed in Ozamiz raid; daughter arrested — police". Inquirer.net. Retrieved July 30, 2017.

^ "Ozamiz City Mayor, twelve others killed in police raid". CNN Philippines. Retrieved July 30, 2017.

^ "Philippine mayor linked to drugs killed in raid: police". France 24. Archived from the original on July 30, 2017. Retrieved July 30, 2017.

^ Salaverria, Leila B.; Corrales, Nestor (16 August 2017). "'That's good,' says Duterte on killing of 32 Bulacan druggies". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Archived from the original on 23 November 2018. Retrieved 4 March 2019.

^ Pilapil, Jaime (August 17, 2017). "25 dead over 24 hours in 'one-time, big-time' police operations in Manila". The Manila Times. Retrieved August 21, 2017.

^ Mogato, Manuel (August 17, 2017). "Philippines war on drugs and crime intensifies, at least 60 killed in three days". Reuters. Retrieved August 21, 2017 – via Swissinfo.ch.

^ Ballaran, Jhoanna; de Jesus, Julianne Love (August 18, 2017). "Senators expressed alarm over high number of drug deaths". Inquirer.net. Philippine Daily Inquirer. Retrieved August 21, 2017.

^ ab "Grade 11 student killed during anti-drug op in Caloocan". GMA News. August 17, 2017. Retrieved August 21, 2017.

^ Subingsubing, Krixia (August 18, 2017). "Cops kill 'pistol-packing' Grade 11 kid". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Retrieved August 21, 2017.

^ "After Kian slay, Duterte tempers messaging on drug war". Rappler. August 26, 2017. Retrieved 29 September 2017.

^ Morallo, Audrey (August 18, 2017). "17-year old's death jolts senators to speak vs. killings". The Philippine Star. Retrieved August 21, 2017.

^ "Human rights commission province 'one time, big time' drug ops, Kian's death". GMA News. August 20, 2017. Retrieved August 21, 2017.

^ "More than a thousand turn Philippine funeral to protest against war on drugs". Reuters. August 26, 2017. Retrieved 2 October 2017.

^ Placido, Dharel (September 6, 2017). "Duterte to pursue raps vs. cops in Carl Angelo's killing". ABS-CBN News. Retrieved September 10, 2017.

^ Requejo, Rey E.; Ramos-Araneta, Macon (8 September 2017). "NBI told to look into De Guzman's killing". Manila Standard. Archived from the original on 10 September 2017. Retrieved 4 March 2019.

^ ab "The death of a Philippine teen was supposed to be a turning point for Duterte. But kids keep getting killed". Washington Post. September 11, 2017. Retrieved 8 October 2017.

^ Salaverria, Leila B. (September 9, 2017). "Teens' killing sabotage-Duterte". Inquirer.net. Philippine Daily Inquirer. Retrieved September 10, 2017.

^ Soriano, Michelle (25 August 2016). "Drug war claims life of 5-year old in Dagupan". ABS-CBN News. Archived from the original on 27 May 2017. Retrieved 4 March 2019.

^ Galarpe, Luel (3 September 2018). "3 cops sued over boy's death in Cebu anti-drug op". Philippine News Agency. Archived from the original on 22 February 2019. Retrieved 4 March 2019.

^ Alquitran, Non; Galupo, Rey (September 16, 2017). "Entire Caloocan City police force sacked". The Philippine Star. Philstar. Retrieved September 18, 2017.

^ "The Mutineer: How Antonio Trillanes Came to Lead the Fight Against Rodrigo Duterte". Time. October 27, 2017. Retrieved October 29, 2017.

^ Roxas, Pathricia Ann V. (8 October 2017). "SWS: Duterte's net satisfaction rating down from 'very good' to 'good'". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Archived from the original on 20 February 2018. Retrieved 4 March 2019.

^ Reuters, Manuel Mogato and Neil Jerome Morales,. "Duterte hopes drug war shift will satisfy 'bleeding hearts'". ABS-CBN News. Retrieved 2017-10-28.

^ Salaverria, Leila B. "I've been demonized in drug war–Duterte". Retrieved 2018-02-28.

^ Salaverria, Leila B. "I've been demonized in drug war–Duterte". Retrieved 2017-10-28.

^ Nonato, Vince F. "Roque to 'reduce impact' of Duterte statements seeming to back rights violations". Retrieved 2017-10-28.

^ ab "Body Count Piles Up in Philippine Drug War". The Wall Street Journal. March 27, 2018. Retrieved October 19, 2018.

^ Osborne, Samuel. "Philippine mayor assassinated day after another was shot dead". The Independent.

^ Lalu, Gabriel Pabico (3 July 2018). "Nueva Ecija mayor dead in ambush". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Archived from the original on 4 March 2019. Retrieved 4 March 2019.

^ "Duterte drug war 'an example to the whole world': Sri Lanka president". ABS-CBN News.

^ "Activists decry Sri Lankan president's praise for Duterte's drugs war". Reuters – via ABS-CBN News.

^ "Deadlier than Iraq: US NGO calls PH 'war zone in disguise'". ABS-CBN News.

^ "SWS: Majority of Filipinos see fewer drug users in their areas". Philippine Daily Inquirer.

^ "Duterte slams Trillanes on 'fewer drug addicts' remark". Philippine Daily Inquirer.

^ "78% of Filipinos worry about being victims of EJK — SWS". CNN Philippines. 2 March 2019. Retrieved 4 March 2019.

^ Sadongdong, Martin (4 March 2019). "Something wrong with way SWS framed questions in EJK survey – PNP chief". Manila Bulletin News. Retrieved 4 March 2019.

^ "Duterte releases drug list ahead of 2019 elections". Rappler.

^ "Duterte names 8 party mates in new drug list". Rappler.

^ "Duterte narco list aims to 'control' May elections, say Otso Diretso bets". Rappler.Another Otso Diretso candidate, former solicitor general Florin Hilbay, shared Alejano’s sentiments, alleging the Duterte administration is using the list to ensure their allies would win in May.

^ "Philippines leaves International Criminal Court". Rappler.

^ "Int'l Criminal Court chief prosecutor warns PH over drug killings". CNN Philippines.

^ Valente, Catherine S.; Pilapil, Jaime (15 October 2016). "Global court warns govt over killings". The Manila Times Online. Agence France Press, TMT. Archived from the original on 15 December 2016. Retrieved 4 March 2019.

^ ab "International court warns PH on killings". Philippine Daily Inquirer.

^ "Statement of the Prosecutor of the International Criminal Court, Mrs Fatou Bensouda, on opening Preliminary Examinations into the situations in the Philippines and in Venezuela".

^ "Philippines Murderous 'Drug War' in ICC Crosshairs". 8 February 2018.

^ "Policy Paper on Preliminary Examinations" (PDF).

^ "Duterte Is Accused of Murder in New Filing at Hague Court". The New York Times. August 28, 2018. Retrieved October 15, 2018.

^ "Philippines' Duterte hit by new ICC complaint over deadly drug war". Reuters. August 28, 2018. Retrieved October 19, 2018.

^ "Nearly all Pinoys trust Duterte: Pulse Asia". ABS-CBN News. 20 July 2016. Archived from the original on 28 October 2017. Retrieved 4 March 2019.

^ "People in the Philippines Still Favor U.S. Over China, but Gap Is Narrowing (2017), Pew Research Center, p. 4" (PDF). Retrieved November 19, 2017.

^ "PNP chief: Illegal drug supply already reduced by 80-90 percent". GMA Network. September 16, 2016.

^ "Dela Rosa: We're winning the war on drugs".

^ "More blood but no victory as Philippine drug war marks its first year". Reuters. 25 June 2017. Retrieved 19 September 2017.

^ "'Foreign investors care about money, not drug deaths' — biz leader". CNN Philippines. September 20, 2016. Retrieved September 21, 2016.

^ "In Duterte's Philippines, Foreigners Flee Stocks". Wall Street Journal. September 20, 2016. Retrieved September 23, 2016.

^ Viray, Patricia Lourdes (30 August 2016). "Tagle: Condemn all forms of killings". The Philippine Star. Archived from the original on 19 December 2017. Retrieved 4 March 2019.

^ abc "Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte's 'War on Drugs'". Human Rights Watch. September 7, 2017. Retrieved 8 October 2017.

^ Alexis Romero (June 14, 2016). "Taiwan confident of stronger ties with Philippines under Duterte". The Philippine Star. Retrieved November 5, 2016.

^ "China supports Duterte's war on drugs". ABS-CBN News. July 9, 2016. Retrieved 22 August 2016.

^ ab "Remarks by H.E. Zhao Jianhua Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary of the People's Republic of China". The Manila Times Online. 29 September 2016. Archived from the original on 2 October 2016. Retrieved 4 March 2019.

^ "Beijing backs Philippine President Duterte's ruthless crackdown on drugs". South China Morning Post. July 20, 2016. Retrieved October 12, 2016.

^ "Indonesia Will Not Adopt the Philippines' 'Shoot on Sight' Policy Against Drug Criminals - Jakarta Globe".

^ "Indonesian anti-drugs chief supports implementing Rodrigo Duterte's Philippine-style drug war…". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. September 8, 2016.

^ "Indonesia' war on drugs=".

^ Giovanni Nilles; Edith Regalado (October 17, 2016). "Brunei asked to support drug war, peace process". The Philippine Star. Retrieved October 19, 2016.

^ Edith Regalado (October 18, 2016). "Brunei backs Philippines in war on drugs". The Philippine Star. Retrieved October 19, 2016.

^ Kamles Kumar (October 25, 2016). "Malaysia won't copy Philippines' deadly drug war, says DPM". The Malay Mail. Retrieved October 25, 2016.

^ "Rodrigo Duterte: Donald Trump Endorsed Deadly War on Drugs as 'The Right Way'". Time.

^ "Rodrigo Duterte Says Donald Trump Endorses His Violent Antidrug Campaign". New York Times. December 3, 2016. Retrieved October 14, 2018.

^ "PH and Singapore One with the War Against Drugs and Terrorism". TheMochaPost. December 16, 2016. Archived from the original on 2017-09-09. Retrieved February 20, 2017.

^ "Philippines' Duterte fierce attack on 'hypocritical' EU". BBC NEws. 21 September 2016. Archived from the original on 1 October 2016. Retrieved 4 March 2019.

^ "Philippines president Rodrigo Duterte tells the EU 'F***you' over his war on drugs". The Independent. September 21, 2016. Retrieved October 2, 2016.

^ "Duterte gives middle finger to EU lawmakers again". Rappler.

^ "Duterte's drug war a 'campaign of mass atrocities': US senators". ABS-CBN News.

^ Patricia Lourdes Viray (October 17, 2016). "US senators want tracking of funds in Philippines amid drug war". The Philippine Star. Retrieved October 19, 2016.

^ Marcelo, Ver (May 5, 2017). "U.S. Senators file bill to block arms export to PH". CNN Philippines. Retrieved May 6, 2017.

^ "Former Colombian Presidents take Philippine Drug War". TheMochaPost. Retrieved February 16, 2017.

^ Gaviria, César (February 7, 2017). "President Duterte Is Repeating My Mistakes". The New York Times. Retrieved February 8, 2017.

^ "Duterte calls Colombian ex-president 'idiot'". Philstar.

^ "Asean, the UN and Sec. Cayetano's sophistry". Philippine Daily Inquirer. November 22, 2017.

^ "How the Philippines defends Duterte's drug war". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 19 November 2017.

^ Inquirer, Philippine Daily. "38 nations ask PH: Stop killings, probe abuses".

^ "38 nations seek end to 'killings'".