Geographer

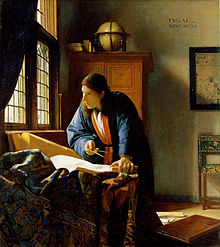

The Geographer (1668-69), by Johannes Vermeer

A geographer is a scientist whose area of study is geography, the study of Earth's natural environment and human society. The Greek prefix, "geo," means "earth" and the Greek suffix, "graphy," meaning "description," so a geographer is someone who studies the earth. The word "geography" is a Middle French word that is believed to have been first used in 1540.[1]

Although geographers are historically known as people who make maps, map making is actually the field of study of cartography, a subset of geography. Geographers do not study only the details of the natural environment or human society, but they also study the reciprocal relationship between these two. For example, they study how the natural environment contributes to the human society and how the human society affects the natural environment.

In particular, physical geographers study the natural environment while human geographers study human society. Modern geographers are the primary practitioners of the GIS (geographic information system), who are often employed by local, state, and federal government agencies as well as in the private sector by environmental and engineering firms.

The paintings by Johannes Vermeer titled The Geographer and The Astronomer are both thought to represent the growing influence and rise in prominence of scientific enquiry in Europe at the time of their painting in 1668–69.

Contents

1 Famous Geographers

1.1 Eratosthenes (Greek)

1.2 Hipparchus (Greek)

1.3 Alexander von Humboldt (German)

1.4 Alfred Russel (A.R.) Wallace (British)

1.5 Richard Francis Burton (British)

1.6 Strabo (Greek)

1.7 Muhammad al-Idrisi (Moroccan)

1.8 Claudius Ptolemy (Ancient Roman)

1.9 Gerardus Mercator (Belgian)

1.10 Charles Lyell (British)

1.11 Pytheas (Greek)

1.12 Douglas Mawson (Australian)

2 Areas of study

3 See also

4 References

5 Further reading

Famous Geographers

Eratosthenes (Greek)

The ancient Greeks discovered much of the knowledge that formed the basis for later scientific and geographical discoveries. Eratosthenes of Cyrene (born circa 276 BCE in Cyrene, Libya; died circa 194 BCE in Alexandria, Egypt) was a Greek writer, poet, astronomer, and geographer who created the first known measurements of the Earth's circumference.[2] Eratosthenes used the angles at which the sun's rays fall on the ground to calculate the curvature of the Earth's surface, which he then used to determine the full horizontal length around the Earth. According to the works of Aristotle, other scientists had estimated the circumference of the Earth prior to Eratosthenes's discovery, but the records of the specific methods and calculations that they used did not survive.[3]

Hipparchus (Greek)

Hipparchus (born in Nicaea, Bithynia [now Iznik, Turkey]; believed to have died after 127 BC in Rhodes) is best known for using astronomical studies to predict the movements and positions of celestial bodies such as the sun, moon, and stars. [4] He discovered the equinoxes (autumnal equinox and spring equinox) and calculated the length of the solar year.[5] Hipparchus was also the first to correctly determine the distance between the earth and the moon (which he believed was equal to 63 times the earth's radius, although it is actually equal to 60 times the earth's radius). Building upon this knowledge, he developed the parallax theory to explain the apparent displacement of celestial bodies relative to the observer's vantage point.[6][7]

Alexander von Humboldt (German)

Alexander von Humboldt (born Sept. 14, 1769 in Berlin; died May 6, 1859) was a German geographer, naturalist and explorer who made major contributions to the field of biogeography by producing break-through research on the connection between the climate of a region and the plant life growing there.[8] The records he kept of his travels provided highly valuable data on the geography of Central Asia, which was not very well understood by Europeans at the time. Furthermore, with the help of Sir Edward Sabine, he was able to prove that the origin of storms is extraterrestrial by showing the relationship between magnetic storms on earth with the changing activity of sun spots.[9] In his latter years, Humboldt published a multi-volume series of books called Kosmos, wherein he described the structure of the universe as it was then understood. Initially, he published four volumes, which were received with great success and were subsequently translated into almost every European language. Humboldt began work on the fifth volume, but died before it was completed (he was ninety years old).[10] The Humboldt Current (also known as the Peru Current), which was named after him, is an ocean current that holds warm air off a 600-mile coastal region between Peru and Chile in South America, thereby keeping the climate cool. Humboldt had explored this region in 1802, and it is now known for containing the world's richest marine ecosystem.[11]

Alfred Russel (A.R.) Wallace (British)

Alfred Russel Wallace, also known as A.R. Wallace, (born on Jan. 8, 1823, in Usk, Monmouthshire, Wales; died on Nov. 7, 1913, in Broadstone, Dorset, England), was a British naturalist, geographer, and social critic who is most known for formulating the theory of evolution by natural selection before Charles Darwin published his famous work on the same subject, The Origin of Species.[12] An avid traveler and explorer, Wallace became both rich and famous from the work he did identifying new animal species in Indonesia and the Amazon region. Importantly, Wallace discovered and defined the concept of "speciation," which he discussed in a paper he published around 1865 describing his research on butterflies. Speciation refers to defining animal species based on their interbreeding capabilities; animals within the same species can breed with each other, but not with animals from other species. In this way, individual species can be identified for scientific classification purposes.[13]

Richard Francis Burton (British)

Sir Richard Francis Burton (born on March 19, 1821, in Torquay, Devonshire, England; died on October 20, 1890, in Trieste, Austria-Hungary [now in Italy]) is known for being the first European to discover Lake Tanganyika in east Africa and for gaining access to Muslim cities, which Europeans had previously been forbidden to access.[14] Lake Tanganyika is estimated to be the second deepest and the second largest freshwater lake in the world and is believed to be one of the oldest lakes in the world (approximately twenty million years old by evolutionary timelines).[15]

Strabo (Greek)

Strabo (born circa 64 BC in Amaseia, Pontus; died some time after 21 AD) was a Greek geographer and historian who left a remarkably comprehensive written record of all the people and countries known to the Greeks and Romans around 27 BC-14 AD. This record, a book called Geography, also provides information on the technology geographers used to study the world at that time as well as the history of the many of the countries mentioned in his records.[16] Although Strabo's account is far from perfect (it assumes, for example, that the earth, then called oikoumene, is one giant landmass consisting of Europe, Asia, Africa, and their associated islands surrounded by a large ocean), his writing is highly valued for being a rich compilation of not only his own observations but also the research and ideas of other respected scientific figures and thinkers including Eratosthenes, Hipparchus, Polybius, Artemidorus, Apollodorus, Aristotle, and Strato.[17]

Muhammad al-Idrisi (Moroccan)

Muhammad al-Idrisi (born in 1100 in Ceutah, Morocco; died around 1165-66 in Ceutah) is known for compiling an enormous world geography for the Norman King of Sicily, Roger II. The book, subsequently named the Book of Roger, was completed in January 1154 and was written as the commentary for a large map of the world created by al-Idrisi (also at the bequest of the King). An avid traveler himself, al-Idrisi relied on contemporary accounts of the world, the works of Ptolemy, as well as geographical literature from Greek, Latin, and Arabic sources to create his work.[18] The Book of Roger contained fairly accurate information on the countries of Europe and was released in several editions although, as of the mid-1900s, the full text had never been edited.

Claudius Ptolemy (Ancient Roman)

Claudius Ptolemy, known simply as Ptolemy, (born around 100 AD; died c. 170 AD) was an astronomer, mathematician, and geographer who lived in Alexandria and is known for (among other things) drawing detailed maps of what was known of the world at the time.[19] Ptolemy's geographical works include tables of latitude and longitude and a discussion of how such lines could be mathematically calculated.[20] In Ptolemy's most famous work, Almagest, he comprehensively describes the layout of the stars and other astronomical objects as understood by ancient Greek and Babylonian scientists. He also put forth the idea of an earth-centered universe, an idea widely believed until the 1500s when Copernicus began to suggest that the earth and other planets in the solar system actually revolve around the sun (called the heliocentric (Sun-centered) theory).[21]

Gerardus Mercator (Belgian)

Gerardus Mercator, originally name Gerard De Cremer or simply Kremer(?) (born on March 5, 1512 in Rupelmonde, Flanders [now in Belgium]; died on December 2, 1594 in Duisburg, Duchy of Cleve [now in Germany]) was a cartographer famous for creating a heart-shaped representation of the earth (also called the "Mercator projection" of the earth) in response to a demand for flat maps that could accurately depict the earth as a spherical object.[22] Mercator was also the first to begin using the term "atlas" to describe a collection of maps.[23] Because of his work, travelers and explorers could maintain a course over long distances using straight lines, thus eliminating the need to constantly adjust their compass readings in order to keep track of their movements.

Charles Lyell (British)

Charles Lyell (1797–1875) was a British geologist whose theory of Uniformitarianism significantly impacted the way modern scientists understand the earth's structure and how this structure can change over time. Uniformitarianism overturned the previously accepted theory of Catastrophism, which held that earth's features were formed by sudden, violent forces rather than by gradual changes over time.[24] Lyell contended that major geological forces in effect today, including volcanic eruptions, earthquakes, and erosion due to wind, water, and gravity, have happened throughout earth's history and are responsible changing its surface features.[25] The theory of evolution is believed to have gained acceptance in part because of Lyell's efforts to promote gradual biological change rather than change due to sudden, extreme events. Building upon the work of James Hutton, Charles Lyell is also responsible for spreading the idea that older rocks are buried underneath newer ones, which led scientists to begin studying fossils and rock layers in order to better understand the history of the earth's geography.[26]

Pytheas (Greek)

Pytheas, a Greek geographer, astronomer, and explorer who lived around 300 bc near Massalia, Gaul (a region comprising mostly modern-day France) is known for producing the first known records of the history of Britain.[27] Pytheas's most important work, On the Ocean, has since been lost, but most of what is known about him was recorded by the Greek historian, Polybius (approx. 200-118 BC). Through travel and detailed observation, Pytheas noticed that the length of the days increased as he traveled northward and that the moon affects the tides in the water. His travels took him to the northernmost parts of Europe including Thule (the northernmost inhabited island, roughly six days sail beyond Britain) and at least to the Arctic Circle (possible Norway or Iceland).[28]

Douglas Mawson (Australian)

Sir Douglas Mawson (born in Yorkshire, England in 1882; died in Brighton, England in 1958) is known for his exploration of Antarctica, although he also studied uranium and other radioactive materials as a preeminent professor of geology at the University of Adelaide in Australia. [29] Along with Edgeworth David and Dr. A.F. Mackay, Mawson was the first man to reach the summit of Mount Erebus, an ice-covered volcanic mountain approximately 11,400 feet high. His expeditions led Britain to surrender its claims over the Antarctic territory to Australia in 1936, and the methods he developed to survive in, and travel through, freezing climates paved the way for subsequent explorations of sub-zero regions.[30]

Areas of study

| History of geography |

|---|

|

|

There are three major fields of study, which are further subdivided:

Physical geography: including geomorphology, hydrology, glaciology, biogeography, climatology, meteorology, pedology, oceanography, geodesy, and environmental geography.

Human geography: including Urban geography, cultural geography, economic geography, political geography, historical geography, marketing geography, health geography, and social geography.

Regional geography: including atmosphere, biosphere, and lithosphere

The National Geographic Society identifies five broad key themes for geographers:

- location

- place

- human-environment interaction

- movement

- regions[31]

See also

- Geography

- Human geography

- List of geographers

- Outline of geography

- Physical geography

- Geographers on Film

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Geographers. |

^ "geography (n.)" (Web article). Online Etymology Dictionary. Douglas Harper. n.d. Retrieved 10 October 2018..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ "Eratosthenes" (Web article). Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, inc. January 25, 2017. Retrieved 5 September 2018.

^ "Eratosthenes" (Web article). Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, inc. January 25, 2017. Retrieved 5 September 2018.

^ "Overview: Hipparchus" (Web.). www.oxfordreference.com. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 23 September 2018.

^ Collins English Dictionary. "Hipparchus" (Web.). www.collinsdictionary.com. HarperCollins Publishers. Retrieved 23 September 2018.

^ "Overview: Hipparchus" (Web.). www.oxfordreference.com. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 23 September 2018.

^ Jones, Alexander Raymond (August 17, 2018). "Hipparchus" (Web.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, inc. Retrieved 23 September 2018.

^ Kellner, Charlotte L. (May 4, 2018). "Alexander von Humboldt" (Web article). Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, inc. Retrieved 5 September 2018.

^ Kellner, Charlotte L. (September 11, 2018). "Alexander von Humboldt" (Web article). Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, inc. Retrieved 16 September 2018.

^ Kellner, Charlotte L. (September 11, 2018). "Alexander von Humboldt" (Web article). Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, inc. Retrieved 16 September 2018.

^ Kiger, Patrick J. (April 12, 2018). "Who Was Alexander von Humboldt and What Is the Humboldt Current?" (Web.). science.howstuffworks.com. HowStuffWorks.com. Retrieved 16 September 2018.

^ Camerini, Jane R. (n.d.). "Alfred Russel Wallace" (Web article.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, inc. Retrieved 30 September 2018.

^ Garrity, Lyn (January 22, 2009). "Out of Darwin's Shadow" (Web article.). www.smithsonianmag.com. Smithsonian.com. Retrieved 30 September 2018.

^ Brodie, Fawn McKay (March 12, 2018). "Sir Richard Burton" (Web article.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, inc. Retrieved 30 September 2018.

^ "Lake Tanganyika" (Web article). www.newworldencyclopedia.org. New World Encyclopedia. June 20, 2018. Retrieved 10 October 2018.

^ "Strabo: Greek Geographer and Historian" (Web article). www.britannica.com. Encyclopeadia Britannica. Retrieved 10 October 2018.

^ "Strabo" (Web article). www.encyclopedia.com. Encyclopedia of World Biography. Retrieved 10 October 2018.

^ (author unknown) (2004). "Muhammad ibn Muhammad al-Idrisi" (Web article). Encyclopedia.com. Encyclopedia of World Biography. Retrieved 14 October 2018.

^ Jones, Alexander Raymond (May 11, 2017). "Ptolemy" (Web article). Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, inc. Retrieved 14 October 2018.

^ World of Earth Science. "Ptolemy (CA. 100-170)" (Web article). https://www.encyclopedia.com. Encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 27 October 2018. External link in|website=(help)

^ "Ptolemy" (Web article). www.newworldencyclopedia.org. New World Encyclopedia. June 15, 2015. Retrieved 27 October 2018.

^ Cavendish, Richard (March 3, 2012). "The Birth of Gerardus Mercator" (Web article). https://www.historytoday.com. History Today Ltd. Retrieved 27 October 2018. External link in|website=(help)

^ The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica (February 26, 2018). "Gerardus Mercator" (Web article). Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, inc. Retrieved 27 October 2018.

^ A Dictionary of Plant Sciences. "catastrophism" (Web article). https://www.encyclopedia.com. Encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 27 October 2018. External link in|website=(help)

^ World of Earth Sciences. "Lyell, Charles (1797-1875)" (Web article). https://www.encyclopedia.com. Encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 27 October 2018. External link in|website=(help)

^ World of Earth Sciences. "Lyell, Charles (1797-1875)" (Web article). https://www.encyclopedia.com. Encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 27 October 2018. External link in|website=(help)

^ Complete Dictionary of Scientific Biography. "Pytheas of Massalia" (Web article). https://www.encyclopedia.com. Encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 27 October 2018. External link in|website=(help)

^ The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica (December 16, 2009). "Pytheas" (Web article). Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, inc. Retrieved 13 November 2018.

^ Encyclopedia of World Biography (2004). "Sir Douglas Mawson" (Web article). Encyclopedia.com. The Gale Group Inc. Retrieved 16 November 2018.

^ Encyclopedia of World Biography (2004). "Sir Douglas Mawson" (Web article). Encyclopedia.com. The Gale Group Inc. Retrieved 16 November 2018.

^ "Geography Education @". Nationalgeographic.com. 2008-10-24. Archived from the original on 2010-02-07. Retrieved 2013-07-16.

Further reading

Steven Seegel. Map Men: Transnational Lives and Deaths of Geographers in the Making of East Central Europe. University of Chicago Press, 2018.

ISBN 978-0-226-43849-8.