Ocean gyre

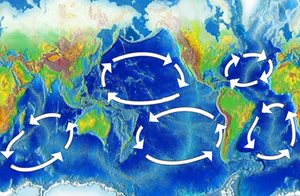

The five major ocean gyres

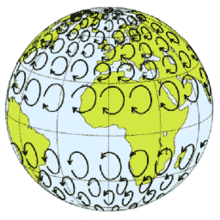

In oceanography, a gyre (/ˈdʒaɪər/) is any large system of circulating ocean currents, particularly those involved with large wind movements. Gyres are caused by the Coriolis effect; planetary vorticity along with horizontal and vertical friction, determine the circulation patterns from the wind stress curl (torque).[1]

The term gyre can be used to refer to any type of vortex in the air or the sea, even one that is man-made, but it is most commonly used in oceanography to refer to the major ocean systems.

Contents

1 Major gyres

2 Other gyres

2.1 Tropical gyres

2.2 Subtropical gyres

2.3 Subpolar gyres

3 Climate change

4 The influence of the Coriolis effect on westward intensification

5 Pollution

6 See also

7 References

8 External links

Major gyres

The following are the five most notable gyres:[2]

Indian Ocean Gyre (generally flowing counter-clockwise)- North Atlantic Gyre

- North Pacific Gyre

- South Atlantic Gyre

- South Pacific Gyre

Other gyres

Tropical gyres

All of the world's larger gyres

Tropical gyres are less unified and tend to be mostly east-west with minor north-south extent.

- Atlantic Equatorial Current System (two counter-rotating circulations)

- Pacific Equatorial Current System

- Indian Monsoon Gyres (two counter-rotating circulations in northern Indian Ocean)[3]

Subtropical gyres

The center of a subtropical gyre is a high pressure zone. Circulation around the high pressure is clockwise in the northern hemisphere and counterclockwise in the southern hemisphere, due to the Coriolis effect. The high pressure in the center is due to the westerly winds on the northern side of the gyre and easterly trade winds on the southern side. These cause frictional surface currents towards the latitude at the center of the gyre.

This build-up of water in the center creates flow towards the equator in the upper 1,000 to 2,000 m (3,300 to 6,600 ft) of the ocean, through rather complex dynamics. This flow is returned towards the pole in an intensified western boundary current. The boundary current of the North Atlantic Gyre is the Gulf Stream, of the North Pacific Gyre the Kuroshio Current, of the South Atlantic Gyre the Brazil Current, of the South Pacific Gyre the East Australian Current, and of the Indian Ocean Gyre the Agulhas Current.

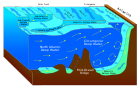

Subpolar gyres

Subpolar gyres form at high latitudes (around 60°). Circulation of surface wind and ocean water is counterclockwise in the Northern Hemisphere, around a low-pressure area, such as the persistent Aleutian Low and the Icelandic Low. Surface currents generally move outward from the center of the system. This drives the Ekman transport, which creates an upwelling of nutrient-rich water from the lower depths.[4]

Subpolar circulation in the southern hemisphere is dominated by the Antarctic Circumpolar Current, due to the lack of large landmasses breaking up the Southern Ocean. There are minor gyres in the Weddell Sea and the Ross Sea, the Weddell Gyre and Ross Gyre, which circulate in a clockwise direction.[2]

Climate change

Recently, stronger winds, especially the subtropical trade winds in the Pacific ocean have provided a mechanism for vertical heat distribution. The effects are changes in the ocean currents, increasing the subtropical overturning, which are also related to the El Niño and La Niña phenomena. Depending on natural variability, during La Niña years around 30% more heat from the upper ocean layer is transported into the deeper ocean.[5] Several studies in recent years, found a multidecadal increase in OHC of the deep and upper ocean regions and attribute the heat uptake to anthropogenic warming.[6]

The influence of the Coriolis effect on westward intensification

Pollution

Ocean gyres are known to collect pollutants. The Great Pacific Garbage Patch in the central North Pacific Ocean is a gyre of marine debris particles and floating trash halfway between Hawaii and California, and extends over an indeterminate area of widely varying range depending on the degree of plastic concentration used to define it. An estimated 80,000 metric tons of plastic inhabit the patch, totaling 1.8 trillion pieces. 92% of the mass in the patch comes from objects larger than 0.5 centimeters.

A similar patch of floating plastic debris is found in the Atlantic Ocean, called the North Atlantic garbage patch. The patch is estimated to be hundreds of kilometers across in size, with a density of over 200,000 pieces of debris per square kilometer.

See also

This article is in a list format that may be better presented using prose. (March 2017) |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Oceanic gyres. |

- Anticyclone

- Cyclone

- Ecosystem of the North Pacific Subtropical Gyre

- Eddy

- Fluid dynamics

- Skookumchuck

- Whirlpool

- Volta do mar

References

^ Heinemann, B. and the Open University (1998) Ocean circulation, Oxford University Press: Page 98

^ ab The five most notable gyres PowerPoint Presentation

^ Indian Monsoon Gyres

^ Wind Driven Surface Currents: Gyres

^ Balmaseda, Trenberth & Källén (2013). "Distinctive climate signals in reanalysis of global ocean heat content". Geophysical Research Letters. 40 (9): 1754–1759. Bibcode:2013GeoRL..40.1754B. doi:10.1002/grl.50382..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ Abraham; et al. (2013). "A review of global ocean temperature observations: Implications for ocean heat content estimates and climate change". Reviews of Geophysics. 51 (3): 450–483. Bibcode:2013RvGeo..51..450A. doi:10.1002/rog.20022.

External links

| Look up Gyre in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- 5 Gyres – Understanding Plastic Marine Pollution

- Wind Driven Surface Currents: Gyres

- SIO 210: Introduction to Physical Oceanography – Global circulation

- SIO 210: Introduction to Physical Oceanography – Wind-forced circulation notes

- SIO 210: Introduction to Physical Oceanography – Lecture 6

- Physical Geography – Surface and Subsurface Ocean Currents

North Pacific Gyre Oscillation — Georgia Institute of Technology