Baden-Baden

Baden-Baden | ||

|---|---|---|

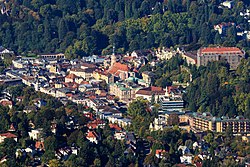

View of Baden-Baden from Mount Merkur. | ||

| ||

Location of Baden-Baden | ||

Baden-Baden Show map of Germany  Baden-Baden Show map of Baden-Württemberg | ||

| Coordinates: 48°45′46″N 08°14′27″E / 48.76278°N 8.24083°E / 48.76278; 8.24083Coordinates: 48°45′46″N 08°14′27″E / 48.76278°N 8.24083°E / 48.76278; 8.24083 | ||

| Country | Germany | |

| State | Baden-Württemberg | |

| Admin. region | Karlsruhe | |

| District | Urban district | |

| Government | ||

| • Mayor | Margret Mergen (CDU) | |

| Area | ||

| • Total | 140.18 km2 (54.12 sq mi) | |

| Elevation | 181 m (594 ft) | |

| Population (2017-12-31)[1] | ||

| • Total | 54,718 | |

| • Density | 390/km2 (1,000/sq mi) | |

| Time zone | CET/CEST (UTC+1/+2) | |

| Postal codes | 76530–76534 | |

| Dialling codes | 07221, 07223 | |

| Vehicle registration | BAD | |

| Website | baden-baden.de | |

Baden-Baden is a spa town in the state of Baden-Württemberg, south-western Germany, at the north-western border of the Black Forest mountain range on the small river Oos, ten kilometres (six miles) east of the Rhine, the border with France, and forty kilometres (twenty-five miles) north-east of Strasbourg, France.

Contents

1 Name

2 Geography

3 History

4 Lord Mayors

5 Tourism

6 Transport

6.1 Road

6.2 Railway

6.3 Air

7 Image gallery

8 International relations

8.1 Twin towns – Sister cities

9 Climate

10 Baden-Baden in art

11 Sons and daughters of the town

11.1 Early times

11.2 19th century

11.3 20th century

12 See also

13 References

14 Bibliography

15 Further reading

16 External links

Name

The springs at Baden-Baden were known to the Romans as Aquae ("The Waters")[2] and Aurelia Aquensis ("Aurelia-of-the-Waters") after M. Aurelius Severus Alexander Augustus.[3]

In modern German, Baden is a noun meaning "bathing"[4] but Baden, the original name of the town, derives from an earlier plural form of Bad ("bath").[5] (The modern plural has become Bäder.)[6] As with the English placename "Bath", various other Badens are at hot springs throughout Central Europe. The current doubled name arose to distinguish it from the others,[5] particularly Baden near Vienna in Austria and Baden near Zürich in Switzerland. It is a reference to the Margraviate of Baden-Baden (1535–1771), a subdivision of the Margraviate of Baden, the territory named after the town. Baden-Baden got its formal name in 1931.[7]

Geography

Baden-Baden lies in a valley[8] of the Northern Black Forest in southwestern Germany.[9] The western districts lie within the Upper Rhine Plain. The highest mountain of Baden-Baden is the Badener Höhe (1,002.5 m above sea level (NHN)[10]), which is part of the Black Forest National Park. The old town lies on the side of a hill on the right bank of the Oos.[8] Since the 19th century, the principal resorts have been located on the other side of the river.[8] There are 29 natural springs in the area, varying in temperature from 46 to 67 °C (115 to 153 °F).[8] The water is rich in salt and flows from artesian wells 1,800 m (5,900 ft) under Florentine Hill[11] at a rate of 341 litre (90 gallons) per minute and is conveyed through pipes to the town's baths.[8]

History

Roman settlement at Baden-Baden has been dated as far back as the emperor Hadrian, but on dubious authority.[3] The known ruins of the Roman bath were rediscovered just below the New Castle in 1847[3] and date to the reign of Caracalla (AD 210s),[9] who visited the area to relieve his arthritic aches.[12] The facilities were used by the Roman garrison in Strasbourg.[9]

The town fell into ruin but its church was first constructed in the 7th century.[9] By 1112, it was the seat of the Margraviate of Baden.[9] The Lichtenthal Convent (Kloster Lichtenthal) was founded in 1254.[9] The margraves initially used Hohenbaden Castle (the Old Castle, Altes Schloss), whose ruins still occupy the summit above the town, but they completed and moved to the New Castle (Neues Schloss) in 1479.[3] Baden suffered severely during the Thirty Years' War, particularly at the hands of the French, who plundered it in 1643.[3] They returned to occupy the city in 1688 at the onset of the Nine Years' War, burning it to the ground the next year.[9] The margravine Sibylla rebuilt the New Castle in 1697, but the margrave Louis William removed his seat to Rastatt in 1706.[3] The Stiftskirche was rebuilt in 1753[9] and houses the tombs of several of the margraves.[3]

The town began its recovery in the late 18th century, serving as a refuge for émigrés from the French Revolution.[9] The town was frequented during the Second Congress of Rastatt in 1797–99[citation needed] and became popular after the visit of the Prussian queen in the early 19th century.[9] She came for medicinal reasons, as the waters were recommended for gout, rheumatism, paralysis, neuralgia, skin disorders, and stones.[13] The Ducal government subsequently subsidized the resort's development.[3] The town became a meeting place for celebrities, who visited the hot springs and the town's other amenities: luxury hotels, the Spielbank Casino,[14] horse races, and the gardens of the Lichtentaler Allee. Guests included Queen Victoria, Wilhelm I, and Berlioz.[12] The pumproom (Trinkhalle) was completed in 1842.[8] The Grand Duchy's railway's mainline reached Baden in 1845.[citation needed] Reaching its zenith under Napoleon III in the 1850s and '60s, Baden became "Europe's summer capital".[9] With a population of around 10 000, the town's size could quadruple during the tourist season, with the French, British, Russians, and Americans all well represented.[8] (French tourism fell off following the Franco-Prussian War.)[13]

The theater was completed in 1861[8] and a Greek church with a gilt dome was erected on the Michaelsberg in 1863 to serve as the tomb of the teenage son of the prince of Moldavia Mihail Sturdza after he died during a family vacation.[15] A Russian Orthodox church was also subsequently erected.[13] The casino was closed for a time in the 1870s.[8]

Just before the First World War, the town was receiving 70 000 visitors each year.[13] The town escaped destruction through both world wars. After World War II, Baden-Baden became the headquarters of the French occupation forces in Germany as well as of the Südwestfunk, one of Germany's large public broadcasting stations, which is now part of Südwestrundfunk. From 23–28 September 1981, the XIth Olympic Congress took place in Baden-Baden's Kurhaus. The Festspielhaus Baden-Baden, Germany's largest opera and concert house, opened in 1998.

CFB Baden-Soellingen, a military airfield built in the 1950s in the Upper Rhine Plain, 10 km (6 mi) west of downtown Baden-Baden, was converted into a civil airport in the 1990s. Karlsruhe/Baden-Baden Airport, or Baden Airpark is now the second-largest airport in Baden-Württemberg by number of passengers.[16]

/* History */ Rudolf Höss (Hoess) was born here November 25, 1901. He was the Commandant of Auschwitz extermination camp in Poland, later relieved of command for impregnating a Jewish prisoner, Eleanor Hodys. Hodys was later murdered by the Gestapo. Höss was executed in Poland for war crimes April 16, 1947 (aged 45).

In 1981 Baden-Baden hosted the Olympic Congress, which later has made the town awarded the designation Olympic town.

Lord Mayors

- 1907–1929: Reinhard Fieser

- 1929–1934: Hermann Elfner

- 1934–1945: Hans Schwedhelm (when he was not in office because of military service, mayor Kurt Bürkle was in office)

- April 1945-May 1945: Ludwig Schmitt

- May 1945-January 1946: Karl Beck

- January 1946-September 1946: Eddy Schacht

- 1946–1969: Ernst Schlapper (CDU) (1888-1976)

- 1969–1990: Walter Carlein (CDU) (1922-2011)

- 1990–1998: Ulrich Wendt (CDU)

- 1998–2006: Sigrun Lang (independent)

- 2006–2014: Wolfgang Gerstner (born 1955), (CDU)

- since June 2014: Margret Mergen (born 1961, (CDU)

Tourism

Baden-Baden is a German spa town.[17] The city offers many options for sports enthusiasts;[12] golf and tennis are both popular in the area.[12] Horse races take place each May, August and October at nearby Iffezheim.[12] The countryside is ideal for hiking and mountain climbing.[12] In the winter Baden-Baden is a skiing destination.[12] There is an 18-hole golf course in Fremersberg.[18]

Sights include:

- The Kurhaus, whose Kurgarten ("Spa Garden") hosts the annual Baden-Baden Summer Nights, featuring live classical music concerts[19]

- Casino

- Friedrichsbad

- Caracalla Spa

Lichtentaler Allee park and gardens

Staatliche Kunsthalle Baden-Baden (State Art Gallery)

Museum Frieder Burda built by Richard Meier for one of Germany's most extensive collections of modern art[20]

- Fabergé Museum

- Museum der Kunst und Technik des 19. Jahrhunderts (Lichtentaler Allee 8), covering the technology of the 19th century

- Kunstmuseum Gehrke-Remund, which exhibits the work of Frida Kahlo

Brahmshaus, Johannes Brahms's residence, which has been preserved as a museum

Hohenbaden Castle or Old Castle, a ruin since the 16th century- New Castle (Neues Schloss), the former residence of the margraves and grand dukes of Baden, now a historical museum[9]

Festspielhaus Baden-Baden, the second-largest festival hall in Europe- Ruins of Roman baths, excavated in 1847

Stiftskirche, a church including the tombs of fourteen margraves of Baden- Paradise (Paradies), an Italian-style Renaissance garden with lots of trick fountains

Mount Merkur, including the Merkurbergbahn funicular railway and observation tower

- Fremersberg Tower

- Sturdza Chapel on the Michaelsberg, a neoclassical chapel with a gilded dome designed by Leo von Klenze which was erected over the tomb of prince Michel Sturdza's son[citation needed]

Transport

Road

The main road link is autobahn A5 between Freiburg and Frankfurt, which is 10km away from the city.

There are two stations providing intercity bus services: one next to the main railway station and one at the airport.[21]

Railway

Baden-Baden has three stations, Baden-Baden station being the most important of them.

Air

Karlsruhe/Baden-Baden Airport is an airport located in Baden-Baden that serves also the city of Karlsruhe. It is the Baden-Württemberg second-largest airport after Stuttgart Airport, and the 18th-largest in Germany with 1,110,500 passengers as of 2016[22] and mostly serves low-cost and leisure flights.

Image gallery

Old Town (Altstadt)

Florentine Hill (Florentinerberg), with the New Castle (top right), the Caracalla Spa (lower right), and the Friedrichsbad (lower left)

Baden-Baden's parish church (Stiftskirche)

The Kurhaus and Casino

The Trinkhalle

Brenner's Park Hotel

The Russian Orthodox Church (Russische Kirche)

The Friedrichsbad, New Castle, and Abbey School (Klosterschule vom Heiligen Grab)

The Spa Shell, an open-air concert venue

Museum Frieder Burda

The Old Castle

International relations

Twin towns – Sister cities

Baden-Baden is twinned with:

|

|

Climate

Climate in this area has mild differences between highs and lows, and there is adequate precipitation year round. The Köppen Climate Classification subtype for this climate is "Cfb" (Marine West Coast Climate/Oceanic climate).[23]

| Climate data for Baden-Baden | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 4 (39) | 6 (42) | 11 (51) | 14 (57) | 19 (66) | 22 (71) | 24 (76) | 24 (76) | 21 (69) | 14 (57) | 8 (46) | 5 (41) | 14 (58) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −1 (30) | −1 (30) | 2 (36) | 4 (39) | 8 (47) | 12 (54) | 14 (57) | 13 (56) | 11 (51) | 7 (44) | 2 (36) | 0 (32) | 6 (43) |

| Average precipitation days | 22 | 18 | 20 | 19 | 21 | 21 | 17 | 16 | 15 | 18 | 18 | 21 | 226 |

| Source: Weatherbase [24] | |||||||||||||

Baden-Baden in art

Baden featured in Tolstoy's Anna Karenina (under an alias)[12] and Turgenev's Smoke. Dostoyevsky wrote The Gambler while compulsively gambling at the town's casino.[14][25]

The 1975 film The Romantic Englishwoman was filmed on location in Baden-Baden, featuring the Brenner's Park Hotel particularly prominently. The 1997 Bollywood movie Dil To Pagal Hai was also shot in the town.[citation needed]

Sons and daughters of the town

Emil Kessler

Anna Zerr

Francis Pigou

Sir William Des Vœux

Alfred Döblin

Tony Marshall in 2009

Early times

Philip II, Margrave of Baden-Baden (1559–1588) was Margrave of Baden-Baden from 1571 to 1588

William, Margrave of Baden-Baden (1593–1677), regent of Baden-Baden between 1621 and 1677.

Ferdinand Maximilian of Baden-Baden (1625–1669), father of the "Türkenlouis" Louis William, Margrave of Baden-Baden

Friedrich, Freiherr von Zoller (1762–1821), Bavarian lieutenant-general who fought in the Napoleonic Wars

19th century

Emil Kessler (1813–1867), entrepreneur, founder of the Maschinenfabrik Esslingen

Anna Zerr (1822–1881), German operatic soprano

Colonel Francis Mahler (1826–1863), officer in the Union Army during the American Civil War

William Hespeler (1830–1921), German-Canadian businessman, immigration agent and a member of the Legislative Assembly of Manitoba

Francis Pigou (1832–1916), Anglican priest

Sir George William Des Vœux (1834–1909), British colonial governor, Governor of Fiji (1880–1885), Governor of Newfoundland (1886–1887) and Governor of Hong Kong (1887–1891)

Franz Carl Müller-Lyer (1857-1916), German psychologist and sociologist, the Müller-Lyer illusion is named after him

Eugene Armbruster (1865–1943), New York City photographer, illustrator, writer, and historian

Max von Baden (1867–1929), last heir of the Grand Duchy of Baden, last chancellor of the Empire

Paul Nikolaus Cossmann (1869–1942 in Theresienstadt), German journalist

Louis II, Prince of Monaco (1870–1949), Prince of Monaco from 1922 to 1949

Joseph Vollmer (1871–1955), German automobile designer, engineer and pioneering tank designer

Édouard Risler (1873–1929), French pianist

Alfred Döblin (1878–1957), German novelist, essayist and doctor

Wilhelm Brückner (1884–1954), officer and chief adjutant of Adolf Hitler

Alfred Kühn (1885–1968), zoologist and geneticist

Frederick Lindemann, 1st Viscount Cherwell (1886–1957), British physicist

Erich Friedrich Schmidt (1897–1964), German and American-naturalized archaeologist

Wolfgang Krull (1899–1971), mathematician

20th century

Rudolf Höss (1900–1947), Nazi, SS commandant of Auschwitz concentration camp, executed for war crimes- Leopold Gutterer (1902–1996), Nazi functionary and politician, state secretary in the Reich Ministry of Public Enlightenment and Propaganda and vice president of the Reichskulturkammer

Reinhold Schneider (1903–1958), writer

Felix Gilbert (1905–1991), German-American historian

Fritz Suhren (1908–1950), SS Nazi concentration camp commandant executed for war crimes

Antoinette Bower (born 1932), British-American actress

Tony Marshall (born 1938), pop and opera singer

Heinz Bosl (1946–1975), German ballet dancer

Elmar Hörig (born 1949), radio and television presenter

Robert HP Platz (born 1951), composer and conductor

Marc Trillard (born 1955), French writer

Andreas Heinecke (born 1955), social entrepreneur and creator of Dialogue in the Dark

Sabine von Maydell (born 1955), actress and author

Jean-Marc Rochette (born 1956), French painter, illustrator and comics creator.

Tobias A. Schliessler (born 1958), German cinematographer

Ann-Marie MacDonald (born 1958), Canadian playwright, novelist, actress and broadcast host

Stefan Anton Reck (born 1960), German orchestra conductor and painter

Birgit Stauch (born 1961), German sculptor, works in bronzes, sculptures, sketches and portraits.

Florian Ballhaus (born 1965), German cinematographer

Alexandra Kamp (born 1966), German model and actress, grew up in Baden-Baden.

Marco Grimm (born 1972), football player, 334 pro appearances

Frank Moser (born 1976), German professional tennis player

Kai Whittaker (born 1985), German CDU politician, member of the Bundestag since 2013

Magdalena Schnurr (born 1992), German ski jumper

See also

- List of reduplicated place names

References

^ "Bevölkerung nach Nationalität und Geschlecht am 31. Dezember 2017". Statistisches Landesamt Baden-Württemberg (in German). 2018..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ Patricia Erfurt-Cooper; Malcolm Cooper (2009). Health and Wellness Tourism: Spas and Hot Springs. Channel View Publications. p. 67. ISBN 978-1-84541-111-4.

^ abcdefgh EB (1878), p. 227.

^ Messinger, Heinz; Türck, Gisela; Willmann, Helmut, eds. (1993), "bath·ing", Langenscheidt's Compact Dictionary: German

^ ab Charnock, "Baden", Local Etymology, p. 23

^ Messinger, Heinz; Türck, Gisela; Willmann, Helmut, eds. (1993), "Bad", Langenscheidt's Compact Dictionary: German

^ Landesarchivdirektion Baden-Württemberg, eds. (1976). Das Land Baden-Württemberg. Amtliche Beschreibung nach Kreisen und Gemeinden. V. Regierungsbezirk Karlsruhe [The State of Baden-Württemberg. Official description of administrative districts and municipalities. Volume 5 Karlsruhe administrative district] (in German). Stuttgart: Kohlhammer. p. 12. ISBN 3-17-002542-2.CS1 maint: Uses editors parameter (link)

^ abcdefghi EB (1878), p. 226.

^ abcdefghijkl EB (2015).

^ Map services of the Federal Agency for Nature Conservation

^ "Caracalla-Therme". Frommer's. Retrieved 2009-05-23.

^ abcdefgh "Introduction to Baden-Baden". Frommer's. Retrieved 15 May 2009..

^ abcd EB (1911).

^ ab "Spielbank". Frommer's. Retrieved 2009-05-26.

^ Winch (1967), Introducing Germany, p. 75

^ "ADV Monthly Traffic Report 12/2011" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-08-13. Retrieved 2012-06-22.

^ Bogue, David. Belgium and the Rhine. Oxford University. p. 102.

^ "Active pursuits". Frommer's. Retrieved 2009-05-29.

^ "Baden-Baden Summer Nights". Frommer's. Archived from the original on 2011-07-11. Retrieved 2009-05-28.

^ "Sammlung Frieder Burda". Frommer's. Retrieved 2009-05-24.

^ "Baden-Baden: Stations". Travelinho.com.

^ Flughafenverband ADV. "Flughafenverband ADV – Unsere Flughäfen: Regionale Stärke, Globaler Anschluss". adv.aero.

^ Climate Summary for Baden Baden

^

"Weatherbase.com". Weatherbase. 2013.

Retrieved on July 6, 2013.

^ "The Russians are Coming (Back)", CNN Traveller, Atlanta: CNN, retrieved 22 July 2009

Bibliography

Baynes, T.S., ed. (1878), , Encyclopædia Britannica, 3 (9th ed.), New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, pp. 226–227

Baynes, T.S., ed. (1878), , Encyclopædia Britannica, 3 (9th ed.), New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, pp. 226–227

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911), , Encyclopædia Britannica, 3 (11th ed.), Cambridge University Press, p. 184

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911), , Encyclopædia Britannica, 3 (11th ed.), Cambridge University Press, p. 184

"Baden-Baden", Encyclopædia Britannica Online, 2015, retrieved 8 October 2015.

Further reading

.mw-parser-output .refbegin{font-size:90%;margin-bottom:0.5em}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ul{list-style-type:none;margin-left:0}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ul>li,.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>dl>dd{margin-left:0;padding-left:3.2em;text-indent:-3.2em;list-style:none}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-100{font-size:100%}

Charles Francis Coghlan, Jr. (1858). Beauties of Baden-Baden. London: F. Coghlan.

Emmrich, Stuart (July 20, 2017). "36 Hours in Baden-Baden, Germany". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331.

External links

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Baden-Baden. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Baden-Baden. |

Official website (in German) (in Spanish) (in French) (in Italian) (in Japanese) (in Russian) (in Chinese)

(in German) (in Spanish) (in French) (in Italian) (in Japanese) (in Russian) (in Chinese)

Kristallnacht in Baden-Baden, Germany on the Yad Vashem website

Baden-Baden Wiki (in German)

"Art and Nightlife Have Baden-Baden Percolating Again", New York Times, July 9, 2006

. The American Cyclopædia. 1879.