Ellipse

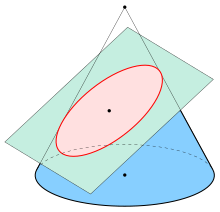

An ellipse (red) obtained as the intersection of a cone with an inclined plane

Ellipse: notations

Ellipses: examples

In mathematics, an ellipse is a curve in a plane surrounding two focal points such that the sum of the distances to the two focal points is constant for every point on the curve. As such, it is a generalization of a circle, which is a special type of an ellipse having both focal points at the same location. The elongation of an ellipse is represented by its eccentricity, which for an ellipse can be any number from 0 (the limiting case of a circle) to arbitrarily close to but less than 1.

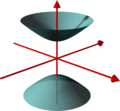

Ellipses are the closed type of conic section: a plane curve resulting from the intersection of a cone by a plane (see figure to the right). Ellipses have many similarities with the other two forms of conic sections: parabolas and hyperbolas, both of which are open and unbounded. The cross section of a cylinder is an ellipse, unless the section is parallel to the axis of the cylinder.

Analytically, an ellipse may also be defined as the set of points such that the ratio of the distance of each point on the curve from a given point (called a focus or focal point) to the distance from that same point on the curve to a given line (called the directrix) is a constant. This ratio is the above-mentioned eccentricity of the ellipse.

An ellipse may also be defined analytically as the set of points for each of which the sum of its distances to two foci is a fixed number.

Ellipses are common in physics, astronomy and engineering. For example, the orbit of each planet in the solar system is approximately an ellipse with the barycenter of the planet–Sun pair at one of the focal points. The same is true for moons orbiting planets and all other systems having two astronomical bodies. The shapes of planets and stars are often well described by ellipsoids. Ellipses also arise as images of a circle under parallel projection and the bounded cases of perspective projection, which are simply intersections of the projective cone with the plane of projection. It is also the simplest Lissajous figure formed when the horizontal and vertical motions are sinusoids with the same frequency. A similar effect leads to elliptical polarization of light in optics.

The name, ἔλλειψις (élleipsis, "omission"), was given by Apollonius of Perga in his Conics, emphasizing the connection of the curve with "application of areas".

Contents

1 Definition of an ellipse as locus of points

2 Ellipse in Cartesian coordinates

2.1 Equation

2.2 Eccentricity

2.3 Semi-latus rectum

2.4 Tangent

2.5 Equation of a shifted ellipse

2.6 Parametric representation

2.6.1 Standard parametric representation

2.6.2 Rational representation

2.6.3 Tangent slope as parameter

2.6.4 Shifted Ellipse

2.7 Parameters a and b

3 Definition of an ellipse by the directrix property

4 The normal bisects the angle between the lines to the foci

5 Ellipse as an affine image of the unit circle x2 + y2 = 1

6 Conjugate diameters and the midpoints of parallel chords

7 Orthogonal tangents

8 Theorem of Apollonios on conjugate diameters

9 Drawing ellipses

9.1 de La Hire's point construction

9.2 Pins-and-string method

9.3 Paper strip methods

9.4 Approximation by osculating circles

9.5 Steiner generation of an ellipse

9.6 Ellipsographs

10 Inscribed angles for ellipses and the 3-point-form

10.1 Circles

10.1.1 Inscribed angle theorem for circles

10.1.2 3-point-form of a circle's equation

10.2 Ellipses

10.2.1 Inscribed angle theorem for ellipses

10.2.2 3-point-form of an ellipse's equation

11 Pole-polar relation for an ellipse

12 Metric properties

12.1 Area

12.2 Circumference

12.3 Curvature

13 Ellipse as quadric

13.1 General ellipse

13.2 Canonical form

14 Polar forms

14.1 Polar form relative to center

14.2 Polar form relative to focus

15 Ellipse as hypotrochoid

16 Ellipses in triangle geometry

17 Ellipses as plane sections of quadrics

18 Applications

18.1 Physics

18.1.1 Elliptical reflectors and acoustics

18.1.2 Planetary orbits

18.1.3 Harmonic oscillators

18.1.4 Phase visualization

18.1.5 Elliptical gears

18.1.6 Optics

18.2 Statistics and finance

18.3 Computer graphics

18.4 Optimization theory

19 See also

20 Notes

21 References

22 External links

Definition of an ellipse as locus of points

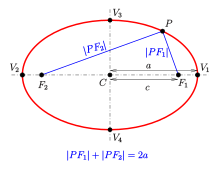

Ellipse: Definition

Ellipse: definition with director circle

An ellipse can be defined geometrically as a set of points (locus of points) in the Euclidean plane:

- An ellipse can be defined using two fixed points, F1{displaystyle F_{1}}

, F2{displaystyle F_{2}}

, called the foci and a distance, usually denoted 2a{displaystyle 2a}

. The ellipse defined with F1{displaystyle F_{1}}

, F2{displaystyle F_{2}}

and 2a{displaystyle 2a}

is the set of points P{displaystyle P}

such that the sum of the distances |PF1|, |PF2|{displaystyle |PF_{1}|, |PF_{2}|}

is constant and equal to 2a{displaystyle 2a}

. In order to omit the special case of a line segment, one assumes 2a>|F1F2|.{displaystyle 2a>|F_{1}F_{2}|.}

More formally, for a given a{displaystyle a}

, an ellipse is the set E={P∈R2∣|PF2|+|PF1|=2a} .{displaystyle E={Pin mathbb {R} ^{2}mid |PF_{2}|+|PF_{1}|=2a} .}

The midpoint C{displaystyle C}

The case F1=F2{displaystyle F_{1}=F_{2}}

The equation |PF2|+|PF1|=2a{displaystyle |PF_{2}|+|PF_{1}|=2a}

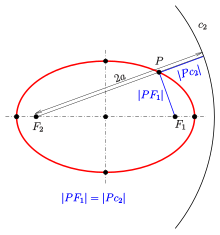

If c2{displaystyle c_{2}}

- |PF1|=|Pc2|.{displaystyle |PF_{1}|=|Pc_{2}|.}

- |PF1|=|Pc2|.{displaystyle |PF_{1}|=|Pc_{2}|.}

c2{displaystyle c_{2}}

Using Dandelin spheres one can prove that any plane section of a cone with a plane, which does not contain the apex and whose slope is less than the slope of the lines on the cone, is an ellipse.

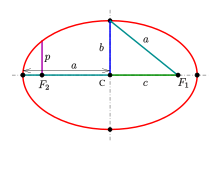

Ellipse in Cartesian coordinates

shape parameters:

a: semi-major axis,

b: semi-minor axis

c: linear eccentricity,

p: semi-latus rectum.

Equation

If Cartesian coordinates are introduced such that the origin is the center of the ellipse and the x-axis is the major axis and

- the foci are the points F1=(c,0), F2=(−c,0){displaystyle F_{1}=(c,0), F_{2}=(-c,0)}

,

- the vertices are V1=(a,0), V2=(−a,0){displaystyle V_{1}=(a,0), V_{2}=(-a,0)}

.

For an arbitrary point (x,y){displaystyle (x,y)}

(x−c)2+y2{displaystyle {sqrt {(x-c)^{2}+y^{2}}}}

- (x−c)2+y2+(x+c)2+y2=2a .{displaystyle {sqrt {(x-c)^{2}+y^{2}}}+{sqrt {(x+c)^{2}+y^{2}}}=2a .}

Remove the square roots by suitable squarings and use the relation b2=a2−c2{displaystyle b^{2}=a^{2}-c^{2}}

- x2a2+y2b2=1,{displaystyle {frac {x^{2}}{a^{2}}}+{frac {y^{2}}{b^{2}}}=1,}

or, solved for y,

- y=±baa2−x2.{displaystyle y=pm {frac {b}{a}}{sqrt {a^{2}-x^{2}}}.}

The shape parameters a,b{displaystyle a,;b}

It follows from the equation that the ellipse is symmetric with respect to both of the coordinate axes and hence symmetric with respect to the origin.

Eccentricity

The eccentricity of an ellipse can be expressed in terms of the ratio of semi-minor and semi-major axes as

- e=1−(ba)2.{displaystyle e={sqrt {1-left({frac {b}{a}}right)^{2}}}.}

This definition relies on the major axis 2a of an ellipse not being shorter than its minor axis 2b. Ellipses with equal axes are simply circles, that is, ellipses with zero eccentricity. The degree of flatness of ellipses increases as their eccentricity does.

Semi-latus rectum

The length of the chord through one of the foci, which is perpendicular to the major axis of the ellipse is called the latus rectum. One half of it is the semi-latus rectum p{displaystyle p}

- p=b2a.{displaystyle p={frac {b^{2}}{a}}.}

The semi-latus rectum p{displaystyle p}

Tangent

An arbitrary line g{displaystyle g}

- The tangent at a point (x0,y0){displaystyle (x_{0},y_{0})}

of the ellipse x2a2+y2b2=1{displaystyle ;{tfrac {x^{2}}{a^{2}}}+{tfrac {y^{2}}{b^{2}}}=1;}

has the coordinate equation

- x0a2x+y0b2y=1.{displaystyle {frac {x_{0}}{a^{2}}}x+{frac {y_{0}}{b^{2}}}y=1;.}

- x0a2x+y0b2y=1.{displaystyle {frac {x_{0}}{a^{2}}}x+{frac {y_{0}}{b^{2}}}y=1;.}

- A vector equation of the tangent is

x→=(x0y0)+s(−y0a2x0b2){displaystyle {vec {x}}={begin{pmatrix}x_{0}\y_{0}end{pmatrix}}+s;{begin{pmatrix}-y_{0}a^{2}\x_{0}b^{2}end{pmatrix}}quad }withs∈R .{displaystyle quad sin mathbb {R} .}

Proof:

Let be (x0,y0){displaystyle (x_{0},y_{0})}

- (x0+su)2a2+(y0+sv)2b2=1 ,⟶2s(x0ua2+y0vb2)+s2(u2a2+v2b2)=0 .{displaystyle {frac {(x_{0}+su)^{2}}{a^{2}}}+{frac {(y_{0}+sv)^{2}}{b^{2}}}=1 ,quad longrightarrow quad 2s;left({frac {x_{0}u}{a^{2}}}+{frac {y_{0}v}{b^{2}}}right)+s^{2};left({frac {u^{2}}{a^{2}}}+{frac {v^{2}}{b^{2}}}right)=0 .}

In case of (1)x0a2u+y0b2v=0{displaystyle ;(1);{tfrac {x_{0}}{a^{2}}}u+{tfrac {y_{0}}{b^{2}}}v=0;}

In case of (2)x0a2u+y0b2v≠0{displaystyle ;(2);{tfrac {x_{0}}{a^{2}}}u+{tfrac {y_{0}}{b^{2}}}vneq 0;}

With help of (1) one finds that (−y0a2,x0b2)T{displaystyle ;(-y_{0}a^{2},x_{0}b^{2})^{T};}

If (x0,y0){displaystyle (x_{0},y_{0})}

x0ua2+y0vb2=0{displaystyle ;{tfrac {x_{0}u}{a^{2}}}+{tfrac {y_{0}v}{b^{2}}}=0;}

Equation of a shifted ellipse

If the ellipse is shifted such that its center is (c1,c2){displaystyle (c_{1},c_{2})}

- (x−c1)2a2+(y−c2)2b2=1 .{displaystyle {frac {(x-c_{1})^{2}}{a^{2}}}+{frac {(y-c_{2})^{2}}{b^{2}}}=1 .}

The axes are still parallel to the x- and y-axes.

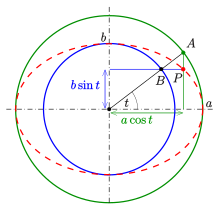

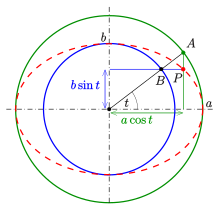

The construction of points based on the parametric equation and the interpretation of parameter t, which is due to de la Hire

Parametric representation

Ellipse points calculated by the rational representation with equal spaced parameters (Δu=0.2{displaystyle Delta u=0.2}

)

)

Standard parametric representation

Using the sine and cosine functions cos,sin{displaystyle cos ,sin }

- (x,y)=(acost,bsint), 0≤t<2π .{displaystyle (x,y)=(acos t,bsin t), 0leq t<2pi .}

Parameter t can be taken as shown in the diagram and is due to de la Hire.[3]

The parameter t (called the eccentric anomaly in astronomy) is not the angle of (x(t),y(t))T{displaystyle (x(t),y(t))^{T}}

Rational representation

With the substitution u=tan(t/2){displaystyle u=tan(t/2)}

- cost=(1−u2)/(u2+1) ,sint=2u/(u2+1){displaystyle cos t=(1-u^{2})/(u^{2}+1) ,quad sin t=2u/(u^{2}+1)}

and the rational parametric equation of an ellipse

- x(u)=a(1−u2)/(u2+1)y(u)=2bu/(u2+1),−∞<u<∞,{displaystyle {begin{array}{lcl}x(u)&=&a(1-u^{2})/(u^{2}+1)\y(u)&=&2bu/(u^{2}+1)end{array}};,quad -infty <u<infty ;,}

which covers any point of the ellipse x2a2+y2b2=1{displaystyle ;{tfrac {x^{2}}{a^{2}}}+{tfrac {y^{2}}{b^{2}}}=1;}

For u∈[0,1],{displaystyle uin [0,1],}![{displaystyle uin [0,1],}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/a2f6453b56211367320bd29f1b315425a4cc9fed)

Rational representations of conic sections are popular with Computer Aided Design (see Bezier curve).

Tangent slope as parameter

A parametric representation, which uses the slope m{displaystyle m}

can be obtained from the derivative of the standard representation x→(t)=(acost,bsint)T{displaystyle {vec {x}}(t)=(acos t,bsin t)^{T}}

- x→′(t)=(−asint,bcost)T→m=−bacott→cott=−mab.{displaystyle {vec {x}}'(t)=(-asin t,bcos t)^{T}quad rightarrow quad m=-{frac {b}{a}}cot tquad rightarrow quad cot t=-{frac {ma}{b}}.}

With help of trigonometric formulae

one gets:

- cost=cott±1+cot2t=−ma±m2a2+b2 ,sint=1±1+cot2t=b±m2a2+b2.{displaystyle cos t={frac {cot t}{pm {sqrt {1+cot ^{2}t}}}}={frac {-ma}{pm {sqrt {m^{2}a^{2}+b^{2}}}}} ,quad quad sin t={frac {1}{pm {sqrt {1+cot ^{2}t}}}}={frac {b}{pm {sqrt {m^{2}a^{2}+b^{2}}}}}.}

Replacing cost{displaystyle cos t}

- c→±(m)=(−ma2±m2a2+b2,b2±m2a2+b2)T,m∈R.{displaystyle {vec {c}}_{pm }(m)=left(-{frac {ma^{2}}{pm {sqrt {m^{2}a^{2}+b^{2}}}}};,;{frac {b^{2}}{pm {sqrt {m^{2}a^{2}+b^{2}}}}}right)^{T},,min mathbb {R} .}

Where m{displaystyle m}

The equation of the tangent at point c→±(m){displaystyle {vec {c}}_{pm }(m)}

- y=mx±m2a2+b2.{displaystyle y=mxpm {sqrt {m^{2}a^{2}+b^{2}}};.}

This description of the tangents of an ellipse is an essential tool for the determination of the orthoptic of an ellipse. The orthoptic article contains another proof, which omits differential calculus and trigonometric formulae.

Shifted Ellipse

A shifted ellipse with center (c1,c2){displaystyle (c_{1},c_{2})}

- (c1+acost,c2+bsint), 0≤t<2π .{displaystyle (c_{1}+acos t;,;c_{2}+bsin t), 0leq t<2pi .}

A parametric representation of an arbitrary ellipse is contained in the section Ellipse as an affine image of the unit circle x2 + y2 = 1 below.

Parameters a and b

The parameters a{displaystyle a}

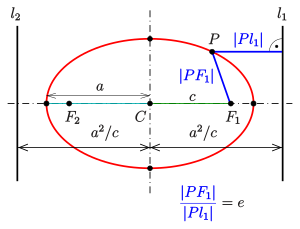

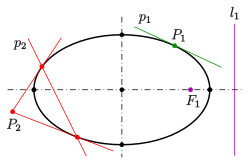

Definition of an ellipse by the directrix property

Ellipse: directrix property

The two lines at distance d=a2c{displaystyle d={frac {a^{2}}{c}}}

- For an arbitrary point P{displaystyle P}

of the ellipse, the quotient of the distance to one focus and to the corresponding directrix (see diagram) is equal to the eccentricity:

- |PF1||Pl1|=|PF2||Pl2|=e=ca .{displaystyle {frac {|PF_{1}|}{|Pl_{1}|}}={frac {|PF_{2}|}{|Pl_{2}|}}=e={frac {c}{a}} .}

- |PF1||Pl1|=|PF2||Pl2|=e=ca .{displaystyle {frac {|PF_{1}|}{|Pl_{1}|}}={frac {|PF_{2}|}{|Pl_{2}|}}=e={frac {c}{a}} .}

The proof for the pair F1,l1{displaystyle F_{1},l_{1}}

- |PF1|2−c2a2|Pl1|2=0 .{displaystyle |PF_{1}|^{2}-{frac {c^{2}}{a^{2}}}|Pl_{1}|^{2}=0 .}

The second case is proven analogously.

The inverse statement is also true and can be used to define an ellipse (in a manner similar to the definition of a parabola):

- For any point F{displaystyle F}

(focus), any line l{displaystyle l}

(directrix) not through F{displaystyle F}

, and any real number e{displaystyle e}

with 0<e<1,{displaystyle 0<e<1,}

the locus of points for which the quotient of the distances to the point and to the line is e,{displaystyle e,}

that is,

- E={P∣|PF||Pl|=e}{displaystyle E=left{Pmid {frac {|PF|}{|Pl|}}=eright}}

- E={P∣|PF||Pl|=e}{displaystyle E=left{Pmid {frac {|PF|}{|Pl|}}=eright}}

- is an ellipse.

The choice e=0{displaystyle e=0}

(The choice e=1{displaystyle e=1}

Pencil of conics with a common vertex and common semi-latus rectum

- Proof

Let F=(f,0), e>0{displaystyle F=(f,0), e>0}

The directrix l{displaystyle l}

(x−f)2+y2=e2(x+fe)2=(ex+f)2{displaystyle (x-f)^{2}+y^{2}=e^{2}left(x+{tfrac {f}{e}}right)^{2}=(ex+f)^{2}}and x2(e2−1)+2xf(1+e)−y2=0.{displaystyle x^{2}(e^{2}-1)+2xf(1+e)-y^{2}=0.}

The substitution p=f(1+e){displaystyle p=f(1+e)}

- x2(e2−1)+2px−y2=0.{displaystyle x^{2}(e^{2}-1)+2px-y^{2}=0.}

This is the equation of an ellipse (e<1{displaystyle e<1}

If e<1{displaystyle e<1}

1−e2=b2a2, and p=b2a{displaystyle 1-e^{2}={tfrac {b^{2}}{a^{2}}},{text{ and }} p={tfrac {b^{2}}{a}}}

- (x−a)2a2+y2b2=1 ,{displaystyle {tfrac {(x-a)^{2}}{a^{2}}}+{tfrac {y^{2}}{b^{2}}}=1 ,}

which is the equation of an ellipse with center (a,0){displaystyle (a,0)}

the major/minor semi axis a,b{displaystyle a,b}

- General case

If the focus is F=(f1,f2){displaystyle F=(f_{1},f_{2})}

- (x−f1)2+(y−f2)2=e2⋅(ux+vy+w)2u2+v2 .{displaystyle left(x-f_{1}right)^{2}+left(y-f_{2}right)^{2}=e^{2}cdot {frac {left(ux+vy+wright)^{2}}{u^{2}+v^{2}}} .}

(The right side of the equation uses the Hesse normal form of a line to calculate the distance |Pl|{displaystyle |Pl|}

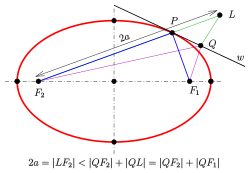

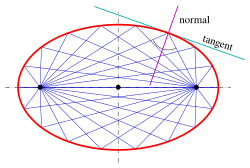

The normal bisects the angle between the lines to the foci

Ellipse: the tangent bisects the supplementary angle of the angle between the lines to the foci.

Rays from one focus reflect off the ellipse to pass through the other focus.

For an ellipse the following statement is true:

- The normal at a point P{displaystyle P}

bisects the angle between the lines PF1¯,PF2¯{displaystyle {overline {PF_{1}}},{overline {PF_{2}}}}

.

- Proof

Because the tangent is perpendicular to the normal, the statement is true for the tangent and the supplementary angle of the angle between the lines to the foci (see diagram), too.

Let L{displaystyle L}

From the diagram and the triangle inequality one recognizes that 2a=|LF2|<|QF2|+|QL|=|QF2|+|QF1|{displaystyle 2a=|LF_{2}|<|QF_{2}|+|QL|=|QF_{2}|+|QF_{1}|}

- Application

The rays from one focus are reflected by the ellipse to the second focus. This property has optical and acoustic applications similar to the reflective property of a parabola (see whispering gallery).

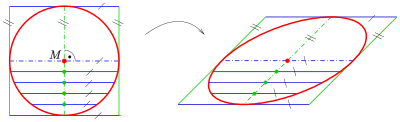

Ellipse as an affine image of the unit circle x2 + y2 = 1

Ellipse as an affine image of the unit circle

Another definition of an ellipse uses affine transformations:

- Any ellipse is the affine image of the unit circle with equation x2+y2=1{displaystyle x^{2}+y^{2}=1}

.

An affine transformation of the Euclidean plane has the form x→→f→0+Ax→{displaystyle {vec {x}}to {vec {f}}_{0}+A{vec {x}}}

- x→=p→(t)=f→0+f→1cost+f→2sint .{displaystyle {vec {x}}={vec {p}}(t)={vec {f}}_{0}+{vec {f}}_{1}cos t+{vec {f}}_{2}sin t .}

f→0{displaystyle {vec {f}}_{0}}

The tangent vector at point p→(t){displaystyle {vec {p}}(t)}

- p→′(t)=−f→1sint+f→2cost .{displaystyle {vec {p}}'(t)=-{vec {f}}_{1}sin t+{vec {f}}_{2}cos t .}

Because at a vertex the tangent is perpendicular to the major/minor axis (diameters) of the ellipse one gets the parameter t0{displaystyle t_{0}}

- p→′(t)⋅(p→(t)−f→0)=(−f→1sint+f→2cost)⋅(f→1cost+f→2sint)=0{displaystyle {vec {p}}'(t)cdot ({vec {p}}(t)-{vec {f}}_{0})=(-{vec {f}}_{1}sin t+{vec {f}}_{2}cos t)cdot ({vec {f}}_{1}cos t+{vec {f}}_{2}sin t)=0}

and hence

cot(2t0)=f→12−f→222f→1⋅f→2{displaystyle cot(2t_{0})={tfrac {{vec {f}}_{1}^{,2}-{vec {f}}_{2}^{,2}}{2{vec {f}}_{1}cdot {vec {f}}_{2}}}}.

(The formulae cos2t−sin2t=cos2t, 2sintcost=sin2t{displaystyle cos ^{2}t-sin ^{2}t=cos 2t, 2sin tcos t=sin 2t}

If f→1⋅f→2=0{displaystyle {vec {f}}_{1}cdot {vec {f}}_{2}=0}

The four vertices of the ellipse are p→(t0),p→(t0±π2),p→(t0+π) .{displaystyle {vec {p}}(t_{0}),;{vec {p}}(t_{0}pm {frac {pi }{2}}),;{vec {p}}(t_{0}+pi ) .}

The advantage of this definition is that one gets a simple parametric representation of an arbitrary ellipse, even in the space, if the vectors f→0,f→1,f→2{displaystyle {vec {f}}_{0},{vec {f}}_{1},{vec {f}}_{2}}

Conjugate diameters and the midpoints of parallel chords

Orthogonal diameters of a circle with a square of tangents, midpoints of parallel chords and an affine image, which is an ellipse with conjugate diameters, a parallelogram of tangents and midpoints of chords

For a circle, the property (M) holds:

(M) The midpoints of parallel chords lie on a diameter.

The diameter and the parallel chords are orthogonal. An affine transformation in general does not preserve orthogonality but does preserve parallelism and midpoints of line segments. Hence: property (M) (which omits the term orthogonal) is true for any ellipse.

- Definition

Two diameters d1,d2{displaystyle d_{1},;d_{2}}

From the diagram one finds:

(T) Two diameters d1:P1Q1¯,d2:P2Q2¯{displaystyle d_{1}:{overline {P_{1}Q_{1}}};,;d_{2}:{overline {P_{2}Q_{2}}}}, of an ellipse are conjugate, if the tangents at P1{displaystyle P_{1}}

and Q1{displaystyle Q_{1}}

are parallel to d2{displaystyle d_{2}}

and visa versa.

The term conjugate diameters is a kind of generalization of orthogonal.

Considering the parametric equation

- x→=p→(t)=f→0+f→1cost+f→2sint{displaystyle {vec {x}}={vec {p}}(t)={vec {f}}_{0}+{vec {f}}_{1}cos t+{vec {f}}_{2}sin t}

of an ellipse, any pair p→(t),p→(t+π){displaystyle {vec {p}}(t),{vec {p}}(t+pi )}

Orthogonal tangents

Ellipse with its orthoptic

For the ellipse x2a2+y2b2=1{displaystyle {tfrac {x^{2}}{a^{2}}}+{tfrac {y^{2}}{b^{2}}}=1}

the intersection points of orthogonal tangents lie on the circle x2+y2=a2+b2{displaystyle x^{2}+y^{2}=a^{2}+b^{2}}

This circle is called orthoptic of the given ellipse.

Theorem of Apollonios on conjugate diameters

Ellipse: theorem of Apollonios on conjugate diameters

For an ellipse with semi-axes a,b{displaystyle a,;b}

- Let c1{displaystyle c_{1}}

and c2{displaystyle c_{2}}

be halves of two conjugate diameters (see diagram) then

c12+c22=a2+b2{displaystyle c_{1}^{2}+c_{2}^{2}=a^{2}+b^{2}},

- the triangle formed by c1,c2{displaystyle c_{1},;c_{2}}

has the constant area AΔ=12ab{displaystyle A_{Delta }={frac {1}{2}}ab}

- the parallelogram of tangents adjacent to the given conjugate diameters has the Area12=4ab .{displaystyle {text{Area}}_{12}=4ab .}

- Proof

Let the ellipse be in the canonical form with parametric equation

p→(t)=(acost,bsint)T{displaystyle {vec {p}}(t)=(acos t,bsin t)^{T}}.

The two points c→1=p→(t), c→2=p→(t+π/2){displaystyle {vec {c}}_{1}={vec {p}}(t), {vec {c}}_{2}={vec {p}}(t+pi /2)}

- |c→1|2+|c→2|2=⋯=a2+b2 .{displaystyle |{vec {c}}_{1}|^{2}+|{vec {c}}_{2}|^{2}=cdots =a^{2}+b^{2} .}

The area of the triangle generated by c→1,c→2{displaystyle {vec {c}}_{1},{vec {c}}_{2}}

- AΔ=12det(c→1,c→2)=⋯=12ab{displaystyle A_{Delta }={tfrac {1}{2}}det({vec {c}}_{1},{vec {c}}_{2})=cdots ={tfrac {1}{2}}ab}

and from the diagram it can be seen that the area of the parallelogram is 8 times that of AΔ{displaystyle A_{Delta }}

- Area12=4ab .{displaystyle {text{Area}}_{12}=4ab .}

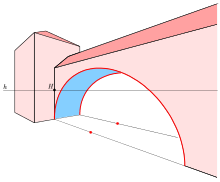

Drawing ellipses

Central projection of circles (gate)

Ellipses appear in descriptive geometry as images (parallel or central projection) of circles. There exist various tools to draw an ellipse. Computers provide the fastest and most accurate method for drawing an ellipse. However, technical tools (ellipsographs) to draw an ellipse without a computer exist. The principle of ellipsographs were known to Greek mathematicians (Archimedes, Proklos).

If there is no ellipsograph available, the best and quickest way to draw an ellipse is to draw an Approximation by the four osculating circles at the vertices.

For any method described below

- the knowledge of the axes and the semi-axes is necessary (or equivalent: the foci and the semi-major axis).

If this presumption is not fulfilled one has to know at least two conjugate diameters. With help of Rytz's construction the axes and semi-axes can be retrieved.

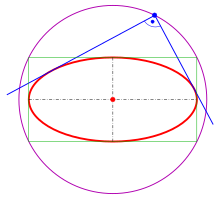

de La Hire's point construction

The following construction of single points of an ellipse is due to de La Hire [4]. It is based on the standard parametric representation (acost,bsint){displaystyle (acos t,bsin t)}

- (1) Draw the two circles centered at the center of the ellipse with radii a,b{displaystyle a,b}

and the axes of the ellipse.

- (2) Draw a line through the center, which intersects the two circles at point A{displaystyle A}

and B{displaystyle B}

, respectively.

- (3) The line through A{displaystyle A}

, which is parallel to the minor axis, meets the line through B{displaystyle B}

, which is parallel to the major axis, at an ellipse point (see diagram).

- (4) Repeat steps (3) and (4) with different lines through the center.

de La Hire's method

Animation of the method

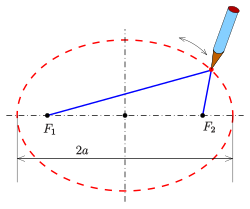

Ellipse: gardener's method

Pins-and-string method

The characterization of an ellipse as the locus of points so that sum of the distances to the foci is constant leads to a method of drawing one using two drawing pins, a length of string, and a pencil. In this method, pins are pushed into the paper at two points, which become the ellipse's foci. A string tied at each end to the two pins and the tip of a pencil pulls the loop taut to form a triangle. The tip of the pencil then traces an ellipse if it is moved while keeping the string taut. Using two pegs and a rope, gardeners use this procedure to outline an elliptical flower bed—thus it is called the gardener's ellipse.

A similar method for drawing confocal ellipses with a closed string is due to the Irish bishop Charles Graves.

Paper strip methods

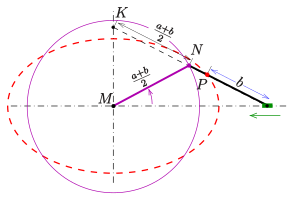

The two following methods rely on the parametric representation (see section parametric representation, above):

- (acost,bsint){displaystyle (acos t,;bsin t)}

This representation can be modeled technically by two simple methods. In both cases center, the axes and semi axes a,b{displaystyle a,;b}

- Method 1

The first method starts with

- a strip of paper of length a+b{displaystyle a+b}

.

The point, where the semi axes meet is marked by P{displaystyle P}

A technical realization of the motion of the paper strip can be achieved by a Tusi couple (s. animation). The device is able to draw any ellipse with a fixed sum a+b{displaystyle a+b}

A nice application: If one stands somewhere in the middle of a ladder, which stands on a slippery ground and leans on a slippery wall, the ladder slides down and the persons feet trace an ellipse.

Ellipse construction: paper strip method 1

Ellipses with Tusi couple. Two examples: red and cyan.

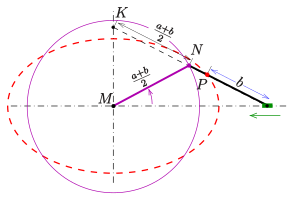

A variation of the paper strip method 1[5] uses the observation that the midpoint N{displaystyle N}

One should be aware that the end, which is sliding on the minor axis, has to be changed.

Variation of the paper strip method 1

Animation of the variation of the paper strip method 1

Ellipse construction: paper strip method 2

- Method 2

The second method starts with

- a strip of paper of length a{displaystyle a}

.

One marks the point, which divides the strip into two substrips of length b{displaystyle b}

This method is the base for several ellipsographs (see section below).

Similar to the variation of the paper strip method 1 a variation of the paper strip method 2 can be established (see diagram) by cutting the part between the axes into halves.

Trammel of Archimedes (principle)

Ellipsograph due to Benjamin Bramer

Variation of the paper strip method 2

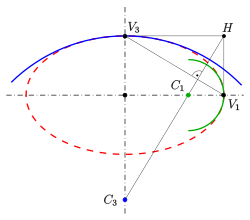

Approximation of an ellipse with osculating circles

Approximation by osculating circles

From section metric properties one gets:

- The radius of curvature at the vertices V1,V2{displaystyle V_{1},V_{2}}

is: b2a ,{displaystyle {tfrac {b^{2}}{a}} ,}

- the radius of curvature at the co-vertices V3,V4{displaystyle V_{3},V_{4}}

is: a2b .{displaystyle {tfrac {a^{2}}{b}} .}

The diagram shows an easy way to find the centers C1=(a−b2a,0),C3=(0,b−a2b){displaystyle C_{1}=(a-{tfrac {b^{2}}{a}},0),;C_{3}=(0,b-{tfrac {a^{2}}{b}})}

- (1) mark the auxiliary point H=(a,b){displaystyle H=(a,b)}

and draw the line segment V1V3 ,{displaystyle V_{1}V_{3} ,}

- (2) draw the line through H{displaystyle H}

, which is perpendicular to the line V1V3 ,{displaystyle V_{1}V_{3} ,}

- (3) the intersection points of this line with the axes are the centers of the osculating circles.

(proof: simple calculation.)

The centers for the remaining vertices are found by symmetry.

With help of a French curve one draws a curve, which has smooth contact to the osculating circles.

Steiner generation of an ellipse

Ellipse: Steiner generation

Ellipse: Steiner generation

The following method to construct single points of an ellipse relies on the Steiner generation of a non degenerate conic section:

- Given two pencils B(U),B(V){displaystyle B(U),B(V)}

of lines at two points U,V{displaystyle U,V}

(all lines containing U{displaystyle U}

and V{displaystyle V}

, respectively) and a projective but not perspective mapping π{displaystyle pi }

of B(U){displaystyle B(U)}

onto B(V){displaystyle B(V)}

, then the intersection points of corresponding lines form a non-degenerate projective conic section.

For the generation of points of the ellipse x2a2+y2b2=1{displaystyle {tfrac {x^{2}}{a^{2}}}+{tfrac {y^{2}}{b^{2}}}=1}

P{displaystyle P}

The Steiner generation also exists for hyperbolas and parabolas. It is sometimes called a parallelogram method because one can use other points rather than the vertices, which starts with a parallelogram instead of a rectangle.

Ellipsographs

Most technical instruments for drawing ellipses are based on the second paperstrip method.

- Ellipsenzirkel (German)

- Drawing instruments

Inscribed angles for ellipses and the 3-point-form

Circles

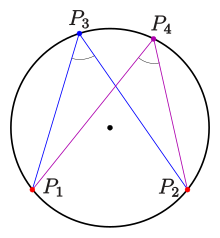

Circle: inscribed angle theorem

A circle with equation (x−c)2+(y−d)2=r2, r>0 ,{displaystyle (x-c)^{2}+(y-d)^{2}=r^{2}, r>0 ,}

- For four points Pi=(xi,yi), i=1,2,3,4,{displaystyle P_{i}=(x_{i},y_{i}), i=1,2,3,4,}

(see diagram) the following statement is true:

- The four points are on a circle if and only if the angles at P3{displaystyle P_{3}}

and P4{displaystyle P_{4}}

are equal.

Usually one measures inscribed angles by degree or radian . In order to get an equation of a circle determined by three points, the following measurement is more convenient:

- In order to measure an angle between two lines with equations y=m1x+d1, y=m2x+d2 ,m1≠m2{displaystyle y=m_{1}x+d_{1}, y=m_{2}x+d_{2} ,m_{1}neq m_{2}}

one uses the quotient

- 1+m1⋅m2m2−m1 .{displaystyle {frac {1+m_{1}cdot m_{2}}{m_{2}-m_{1}}} .}

- 1+m1⋅m2m2−m1 .{displaystyle {frac {1+m_{1}cdot m_{2}}{m_{2}-m_{1}}} .}

- This expression is the cotangent of the angle between the two lines.

Inscribed angle theorem for circles

- For four points Pi=(xi,yi), i=1,2,3,4,{displaystyle P_{i}=(x_{i},y_{i}), i=1,2,3,4,}

, no three of them on a line (see diagram), the following statement is true:

- The four points are on a circle, if and only if the angles at P3{displaystyle P_{3}}

and P4{displaystyle P_{4}}

are equal. In the sense of the measurement above, that means, if

- (x4−x1)(x4−x2)+(y4−y1)(y4−y2)(y4−y1)(x4−x2)−(y4−y2)(x4−x1)=(x3−x1)(x3−x2)+(y3−y1)(y3−y2)(y3−y1)(x3−x2)−(y3−y2)(x3−x1){displaystyle {frac {(x_{4}-x_{1})(x_{4}-x_{2})+(y_{4}-y_{1})(y_{4}-y_{2})}{(y_{4}-y_{1})(x_{4}-x_{2})-(y_{4}-y_{2})(x_{4}-x_{1})}}={frac {(x_{3}-x_{1})(x_{3}-x_{2})+(y_{3}-y_{1})(y_{3}-y_{2})}{(y_{3}-y_{1})(x_{3}-x_{2})-(y_{3}-y_{2})(x_{3}-x_{1})}}}

- (x4−x1)(x4−x2)+(y4−y1)(y4−y2)(y4−y1)(x4−x2)−(y4−y2)(x4−x1)=(x3−x1)(x3−x2)+(y3−y1)(y3−y2)(y3−y1)(x3−x2)−(y3−y2)(x3−x1){displaystyle {frac {(x_{4}-x_{1})(x_{4}-x_{2})+(y_{4}-y_{1})(y_{4}-y_{2})}{(y_{4}-y_{1})(x_{4}-x_{2})-(y_{4}-y_{2})(x_{4}-x_{1})}}={frac {(x_{3}-x_{1})(x_{3}-x_{2})+(y_{3}-y_{1})(y_{3}-y_{2})}{(y_{3}-y_{1})(x_{3}-x_{2})-(y_{3}-y_{2})(x_{3}-x_{1})}}}

At first the measure is available for chords, which are not parallel to the y-axis, only. But the final formula works for any chord.

A consequence of the inscribed angle theorem for circles is the

3-point-form of a circle's equation

- One gets the equation of the circle determined by 3 points Pi=(xi,yi){displaystyle P_{i}=(x_{i},y_{i})}

not on a line by a conversion of the equation

- (x−x1)(x−x2)+(y−y1)(y−y2)(y−y1)(x−x2)−(y−y2)(x−x1)=(x3−x1)(x3−x2)+(y3−y1)(y3−y2)(y3−y1)(x3−x2)−(y3−y2)(x3−x1) .{displaystyle {frac {({color {green}x}-x_{1})({color {green}x}-x_{2})+({color {red}y}-y_{1})({color {red}y}-y_{2})}{({color {red}y}-y_{1})({color {green}x}-x_{2})-({color {red}y}-y_{2})({color {green}x}-x_{1})}}={frac {(x_{3}-x_{1})(x_{3}-x_{2})+(y_{3}-y_{1})(y_{3}-y_{2})}{(y_{3}-y_{1})(x_{3}-x_{2})-(y_{3}-y_{2})(x_{3}-x_{1})}} .}

- (x−x1)(x−x2)+(y−y1)(y−y2)(y−y1)(x−x2)−(y−y2)(x−x1)=(x3−x1)(x3−x2)+(y3−y1)(y3−y2)(y3−y1)(x3−x2)−(y3−y2)(x3−x1) .{displaystyle {frac {({color {green}x}-x_{1})({color {green}x}-x_{2})+({color {red}y}-y_{1})({color {red}y}-y_{2})}{({color {red}y}-y_{1})({color {green}x}-x_{2})-({color {red}y}-y_{2})({color {green}x}-x_{1})}}={frac {(x_{3}-x_{1})(x_{3}-x_{2})+(y_{3}-y_{1})(y_{3}-y_{2})}{(y_{3}-y_{1})(x_{3}-x_{2})-(y_{3}-y_{2})(x_{3}-x_{1})}} .}

Using vectors, dot products and determinants this formula can be arranged more clearly:

- (x→−x→1)⋅(x→−x→2)det(x→−x→1,x→−x→2)=(x→3−x→1)⋅(x→3−x→2)det(x→3−x→1,x→3−x→2).{displaystyle {frac {({color {red}{vec {x}}}-{vec {x}}_{1})cdot ({color {red}{vec {x}}}-{vec {x}}_{2})}{det({color {red}{vec {x}}}-{vec {x}}_{1},{color {red}{vec {x}}}-{vec {x}}_{2})}}={frac {({vec {x}}_{3}-{vec {x}}_{1})cdot ({vec {x}}_{3}-{vec {x}}_{2})}{det({vec {x}}_{3}-{vec {x}}_{1},{vec {x}}_{3}-{vec {x}}_{2})}};.}

- (x→−x→1)⋅(x→−x→2)det(x→−x→1,x→−x→2)=(x→3−x→1)⋅(x→3−x→2)det(x→3−x→1,x→3−x→2).{displaystyle {frac {({color {red}{vec {x}}}-{vec {x}}_{1})cdot ({color {red}{vec {x}}}-{vec {x}}_{2})}{det({color {red}{vec {x}}}-{vec {x}}_{1},{color {red}{vec {x}}}-{vec {x}}_{2})}}={frac {({vec {x}}_{3}-{vec {x}}_{1})cdot ({vec {x}}_{3}-{vec {x}}_{2})}{det({vec {x}}_{3}-{vec {x}}_{1},{vec {x}}_{3}-{vec {x}}_{2})}};.}

For example, for P1=(2,0),P2=(0,1),P3=(0,0){displaystyle P_{1}=(2,0),;P_{2}=(0,1),;P_{3}=(0,0)}

(x−2)x+y(y−1)yx−(y−1)(x−2)=0{displaystyle {frac {(x-2)x+y(y-1)}{yx-(y-1)(x-2)}}=0}, which can be rearranged to (x−1)2+(y−1/2)2=5/4 .{displaystyle (x-1)^{2}+(y-1/2)^{2}=5/4 .}

Ellipses

This section considers ellipses with an equation

- (x−c)2a2+(y−d)2b2=1↔(x−c)2+a2b2(y−d)2=a2,c,d,∈R, a>0 ,{displaystyle {frac {(x-c)^{2}}{a^{2}}}+{frac {(y-d)^{2}}{b^{2}}}=1quad leftrightarrow quad (x-c)^{2}+{frac {a^{2}}{b^{2}}}(y-d)^{2}=a^{2},quad c,d,in mathbb {R} , a>0 ,}

where the ratio a2b2{displaystyle {frac {a^{2}}{b^{2}}}}

With the abbreviation q=a2b2 {displaystyle {color {blue}q}={frac {a^{2}}{b^{2}}} }

(x−c)2+q(y−d)2=a2,c,d∈R,a>0{displaystyle (x-c)^{2}+{color {blue}q};(y-d)^{2}=a^{2},quad c,din mathbb {R} ,;a>0;}and q>0{displaystyle ;q>0;}

fixed.

Such ellipses have their axes parallel to the coordinate axes and their eccentricity fixed. Their major axes are parallel to the x-axis if q>1{displaystyle q>1}

Inscribed angle theorem for an ellipse

Like a circle, such an ellipse is determined by three points not on a line.

In this more general case one introduces the following measurement of an angle,:[6][7]

- In order to measure an angle between two lines with equations y=m1x+d1, y=m2x+d2 ,m1≠m2{displaystyle y=m_{1}x+d_{1}, y=m_{2}x+d_{2} ,m_{1}neq m_{2}}

one uses the quotient

- 1+qm1⋅m2m2−m1 .{displaystyle {frac {1+{color {blue}q};m_{1}cdot m_{2}}{m_{2}-m_{1}}} .}

- 1+qm1⋅m2m2−m1 .{displaystyle {frac {1+{color {blue}q};m_{1}cdot m_{2}}{m_{2}-m_{1}}} .}

Inscribed angle theorem for ellipses

- For four points Pi=(xi,yi), i=1,2,3,4,{displaystyle P_{i}=(x_{i},y_{i}), i=1,2,3,4,}

, no three of them on a line (see diagram), the following statement is true:

- The four points are on an ellipse with equation (x−c)2+q(y−d)2=a2{displaystyle (x-c)^{2}+q;(y-d)^{2}=a^{2}}

, if and only if the angles at P3{displaystyle P_{3}}

and P4{displaystyle P_{4}}

are equal in the sense of the measurement above—that is, if

- (x4−x1)(x4−x2)+q(y4−y1)(y4−y2)(y4−y1)(x4−x2)−(y4−y2)(x4−x1)=(x3−x1)(x3−x2)+q(y3−y1)(y3−y2)(y3−y1)(x3−x2)−(y3−y2)(x3−x1) .{displaystyle {frac {(x_{4}-x_{1})(x_{4}-x_{2})+{color {blue}q};(y_{4}-y_{1})(y_{4}-y_{2})}{(y_{4}-y_{1})(x_{4}-x_{2})-(y_{4}-y_{2})(x_{4}-x_{1})}}={frac {(x_{3}-x_{1})(x_{3}-x_{2})+{color {blue}q};(y_{3}-y_{1})(y_{3}-y_{2})}{(y_{3}-y_{1})(x_{3}-x_{2})-(y_{3}-y_{2})(x_{3}-x_{1})}} .}

- (x4−x1)(x4−x2)+q(y4−y1)(y4−y2)(y4−y1)(x4−x2)−(y4−y2)(x4−x1)=(x3−x1)(x3−x2)+q(y3−y1)(y3−y2)(y3−y1)(x3−x2)−(y3−y2)(x3−x1) .{displaystyle {frac {(x_{4}-x_{1})(x_{4}-x_{2})+{color {blue}q};(y_{4}-y_{1})(y_{4}-y_{2})}{(y_{4}-y_{1})(x_{4}-x_{2})-(y_{4}-y_{2})(x_{4}-x_{1})}}={frac {(x_{3}-x_{1})(x_{3}-x_{2})+{color {blue}q};(y_{3}-y_{1})(y_{3}-y_{2})}{(y_{3}-y_{1})(x_{3}-x_{2})-(y_{3}-y_{2})(x_{3}-x_{1})}} .}

At first the measure is available only for chords which are not parallel to the y-axis. But the final formula works for any chord. The proof follows from a straightforward calculation. For the direction of proof given that the points are on an ellipse, one can assume that the center of the ellipse is the origin.

A consequence of the inscribed angle theorem for ellipses is the

3-point-form of an ellipse's equation

- One gets the equation of the ellipse determined by 3 points Pi=(xi,yi){displaystyle P_{i}=(x_{i},y_{i})}

not on a line by a conversion of the equation

- (x−x1)(x−x2)+q(y−y1)(y−y2)(y−y1)(x−x2)−(y−y2)(x−x1)=(x3−x1)(x3−x2)+q(y3−y1)(y3−y2)(y3−y1)(x3−x2)−(y3−y2)(x3−x1) .{displaystyle {frac {({color {green}x}-x_{1})({color {green}x}-x_{2})+{color {blue}q};({color {red}y}-y_{1})({color {red}y}-y_{2})}{({color {red}y}-y_{1})({color {green}x}-x_{2})-({color {red}y}-y_{2})({color {green}x}-x_{1})}}={frac {(x_{3}-x_{1})(x_{3}-x_{2})+{color {blue}q};(y_{3}-y_{1})(y_{3}-y_{2})}{(y_{3}-y_{1})(x_{3}-x_{2})-(y_{3}-y_{2})(x_{3}-x_{1})}} .}

- (x−x1)(x−x2)+q(y−y1)(y−y2)(y−y1)(x−x2)−(y−y2)(x−x1)=(x3−x1)(x3−x2)+q(y3−y1)(y3−y2)(y3−y1)(x3−x2)−(y3−y2)(x3−x1) .{displaystyle {frac {({color {green}x}-x_{1})({color {green}x}-x_{2})+{color {blue}q};({color {red}y}-y_{1})({color {red}y}-y_{2})}{({color {red}y}-y_{1})({color {green}x}-x_{2})-({color {red}y}-y_{2})({color {green}x}-x_{1})}}={frac {(x_{3}-x_{1})(x_{3}-x_{2})+{color {blue}q};(y_{3}-y_{1})(y_{3}-y_{2})}{(y_{3}-y_{1})(x_{3}-x_{2})-(y_{3}-y_{2})(x_{3}-x_{1})}} .}

Analogously to the circle case this formula can be written more clearly using vectors:

- (x→−x→1)∗(x→−x→2)det(x→−x→1,x→−x→2)=(x→3−x→1)∗(x→3−x→2)det(x→3−x→1,x→3−x→2),{displaystyle {frac {({color {red}{vec {x}}}-{vec {x}}_{1})*({color {red}{vec {x}}}-{vec {x}}_{2})}{det({color {red}{vec {x}}}-{vec {x}}_{1},{color {red}{vec {x}}}-{vec {x}}_{2})}}={frac {({vec {x}}_{3}-{vec {x}}_{1})*({vec {x}}_{3}-{vec {x}}_{2})}{det({vec {x}}_{3}-{vec {x}}_{1},{vec {x}}_{3}-{vec {x}}_{2})}};,}

- (x→−x→1)∗(x→−x→2)det(x→−x→1,x→−x→2)=(x→3−x→1)∗(x→3−x→2)det(x→3−x→1,x→3−x→2),{displaystyle {frac {({color {red}{vec {x}}}-{vec {x}}_{1})*({color {red}{vec {x}}}-{vec {x}}_{2})}{det({color {red}{vec {x}}}-{vec {x}}_{1},{color {red}{vec {x}}}-{vec {x}}_{2})}}={frac {({vec {x}}_{3}-{vec {x}}_{1})*({vec {x}}_{3}-{vec {x}}_{2})}{det({vec {x}}_{3}-{vec {x}}_{1},{vec {x}}_{3}-{vec {x}}_{2})}};,}

where ∗{displaystyle *}

For example, for P1=(2,0),P2=(0,1),P3=(0,0){displaystyle P_{1}=(2,0),;P_{2}=(0,1),;P_{3}=(0,0)}

(x−2)x+4y(y−1)yx−(y−1)(x−2)=0{displaystyle {frac {(x-2)x+4y(y-1)}{yx-(y-1)(x-2)}}=0;}and after conversion (x−1)22+(y−1/2)21/2=1.{displaystyle ;{frac {(x-1)^{2}}{2}}+{frac {(y-1/2)^{2}}{1/2}}=1;.}

Pole-polar relation for an ellipse

Ellipse: pole-polar relation

Any ellipse can be described in a suitable coordinate system by an equation x2a2+y2b2=1{displaystyle {tfrac {x^{2}}{a^{2}}}+{tfrac {y^{2}}{b^{2}}}=1}

- point P0=(x0,y0)≠(0,0){displaystyle P_{0}=(x_{0},y_{0})neq (0,0)}

is mapped onto the line x0xa2+y0yb2=1{displaystyle {frac {x_{0}x}{a^{2}}}+{frac {y_{0}y}{b^{2}}}=1}

, not through the center of the ellipse.

This relation between points and lines is a bijection.

The inverse function maps

- line y=mx+d, d≠0{displaystyle y=mx+d, dneq 0}

onto the point (−ma2d,b2d){displaystyle left(-{frac {ma^{2}}{d}},{frac {b^{2}}{d}}right)}

and

- line x=c, c≠0{displaystyle x=c, cneq 0}

onto the point (a2c,0) .{displaystyle left({frac {a^{2}}{c}},0right) .}

Such a relation between points and lines generated by a conic is called pole-polar relation or just polarity. The pole is the point, the polar the line. See Pole and polar.

By calculation one can confirm the following properties of the pole-polar relation of the ellipse:

- For a point (pole) on the ellipse the polar is the tangent at this point (see diagram: P1, p1{displaystyle P_{1}, p_{1}}

).

- For a pole P{displaystyle P}

outside the ellipse the intersection points of its polar with the ellipse are the tangency points of the two tangents passing P{displaystyle P}

(see diagram: P2, p2{displaystyle P_{2}, p_{2}}

).

- For a point within the ellipse the polar has no point with the ellipse in common. (see diagram: F1, l1{displaystyle F_{1}, l_{1}}

).

- The intersection point of two polars is the pole of the line through their poles.

- The foci (c,0),{displaystyle (c,0),}

and (−c,0){displaystyle (-c,0)}

respectively and the directrices x=a2c{displaystyle x={tfrac {a^{2}}{c}}}

and x=−a2c{displaystyle x=-{tfrac {a^{2}}{c}}}

respectively belong to pairs of pole and polar.

Pole-polar relations exist for hyperbolas and parabolas, too.

Metric properties

All metric properties given below refer to an ellipse with equation x2a2+y2b2=1{displaystyle {frac {x^{2}}{a^{2}}}+{frac {y^{2}}{b^{2}}}=1}

Area

The area Aellipse{displaystyle A_{text{ellipse}}}

- Aellipse=πab{displaystyle A_{text{ellipse}}=pi ab}

where a{displaystyle a}

![{displaystyle xin [-a,a],}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/fb19e5015712fa6f6c57d3f334266c73d7782434)

![[-a,a]](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/50ccbcece37f9ec0a4c6d396be3a143a0b76d5c1)

- Aellipse=∫−aa2b1−x2/a2dx=ba∫−aa2a2−x2dx.{displaystyle {begin{aligned}A_{text{ellipse}}&=int _{-a}^{a}2b{sqrt {1-x^{2}/a^{2}}},dx\&={frac {b}{a}}int _{-a}^{a}2{sqrt {a^{2}-x^{2}}},dx.end{aligned}}}

The second integral is the area of a circle of radius a,{displaystyle a,}

- Aellipse=baπa2=πab.{displaystyle A_{text{ellipse}}={frac {b}{a}}pi a^{2}=pi ab.}

An ellipse defined implicitly by Ax2+Bxy+Cy2=1{displaystyle Ax^{2}+Bxy+Cy^{2}=1}

The area can also be expressed in terms of eccentricity and the length of the semi-major axis as a2π1−e2{displaystyle a^{2}pi {sqrt {1-e^{2}}}}

Circumference

The circumference C{displaystyle C}

- C=4a∫0π/21−e2sin2θ dθ=4aE(e){displaystyle C=4aint _{0}^{pi /2}{sqrt {1-e^{2}sin ^{2}theta }} dtheta =4aE(e)}

where again a{displaystyle a}

- E(e)=∫0π/21−e2sin2θ dθ.{displaystyle E(e)=int _{0}^{pi /2}{sqrt {1-e^{2}sin ^{2}theta }} dtheta .}

The circumference of the ellipse may be evaluated in terms of E(e){displaystyle E(e)}

The exact infinite series is:

- C=2πa[1−(12)2e2−(1⋅32⋅4)2e43−(1⋅3⋅52⋅4⋅6)2e65−⋯]{displaystyle C=2pi aleft[{1-left({frac {1}{2}}right)^{2}e^{2}-left({frac {1cdot 3}{2cdot 4}}right)^{2}{frac {e^{4}}{3}}-left({frac {1cdot 3cdot 5}{2cdot 4cdot 6}}right)^{2}{frac {e^{6}}{5}}-cdots }right]}

- =2πa[1−∑n=1∞((2n−1)!!(2n)!!)2e2n2n−1],{displaystyle =2pi aleft[1-sum _{n=1}^{infty }left({frac {(2n-1)!!}{(2n)!!}}right)^{2}{frac {e^{2n}}{2n-1}}right],}

where n!!{displaystyle n!!}

- C=π(a+b)[1+∑n=1∞((2n−1)!!2nn!)2hn(2n−1)2].{displaystyle C=pi (a+b)left[1+sum _{n=1}^{infty }left({frac {(2n-1)!!}{2^{n}n!}}right)^{2}{frac {h^{n}}{(2n-1)^{2}}}right].}

Ramanujan gives two good approximations for the circumference in §16 of "Modular Equations and Approximations to π{displaystyle pi }

- C≈π[3(a+b)−(3a+b)(a+3b)]=π[3(a+b)−10ab+3(a2+b2)]{displaystyle Capprox pi left[3(a+b)-{sqrt {(3a+b)(a+3b)}}right]=pi left[3(a+b)-{sqrt {10ab+3(a^{2}+b^{2})}}right]}

and

- C≈π(a+b)(1+3h10+4−3h).{displaystyle Capprox pi left(a+bright)left(1+{frac {3h}{10+{sqrt {4-3h}}}}right).}

The errors in these approximations, which were obtained empirically, are of order h3{displaystyle h^{3}}

More generally, the arc length of a portion of the circumference, as a function of the angle subtended, is given by an incomplete elliptic integral.

The inverse function, the angle subtended as a function of the arc length, is given by the elliptic functions.[citation needed]

Some lower and upper bounds on the circumference of the canonical ellipse x2/a2+y2/b2=1{displaystyle x^{2}/a^{2}+y^{2}/b^{2}=1}

- 2πb≤C≤2πa,{displaystyle 2pi bleq Cleq 2pi a,}

- π(a+b)≤C≤4(a+b),{displaystyle pi (a+b)leq Cleq 4(a+b),}

- 4a2+b2≤C≤2πa2+b2.{displaystyle 4{sqrt {a^{2}+b^{2}}}leq Cleq {sqrt {2}}pi {sqrt {a^{2}+b^{2}}}.}

Here the upper bound 2πa{displaystyle 2pi a}

Curvature

The curvature is given by κ=1a2b2(x2a4+y2b4)−32 ,{displaystyle kappa ={frac {1}{a^{2}b^{2}}}left({frac {x^{2}}{a^{4}}}+{frac {y^{2}}{b^{4}}}right)^{-{frac {3}{2}}} ,}

radius of curvature at point (x,y){displaystyle (x,y)}

- ρ=a2b2(x2a4+y2b4)3/2=1a4b4(a4y2+b4x2)3 .{displaystyle rho =a^{2}b^{2}left({frac {x^{2}}{a^{4}}}+{frac {y^{2}}{b^{4}}}right)^{3/2}={frac {1}{a^{4}b^{4}}}{sqrt {left(a^{4}y^{2}+b^{4}x^{2}right)^{3}}} .}

Radius of curvature at the two vertices (±a,0){displaystyle (pm a,0)}

- ρ0=b2a=p ,(±c2a|0) .{displaystyle rho _{0}={frac {b^{2}}{a}}=p ,qquad left(pm {frac {c^{2}}{a}},{bigg |},0right) .}

Radius of curvature at the two co-vertices (0,±b){displaystyle (0,pm b)}

- ρ1=a2b ,(0|±c2b) .{displaystyle rho _{1}={frac {a^{2}}{b}} ,qquad left(0,{bigg |},pm {frac {c^{2}}{b}}right) .}

Ellipse as quadric

General ellipse

In analytic geometry, the ellipse is defined as a quadric: the set of points (X,Y){displaystyle (X,Y)}

- AX2+BXY+CY2+DX+EY+F=0{displaystyle ~AX^{2}+BXY+CY^{2}+DX+EY+F=0}

provided B2−4AC<0.{displaystyle B^{2}-4AC<0.}

To distinguish the degenerate cases from the non-degenerate case, let ∆ be the determinant

- |AB/2D/2B/2CE/2D/2E/2F|;{displaystyle {begin{vmatrix}A&B/2&D/2\B/2&C&E/2\D/2&E/2&Fend{vmatrix}};}

that is,

- Δ=(AC−B24)F+BED4−CD24−AE24.{displaystyle Delta =left(AC-{frac {B^{2}}{4}}right)F+{frac {BED}{4}}-{frac {CD^{2}}{4}}-{frac {AE^{2}}{4}}.}

Then the ellipse is a non-degenerate real ellipse if and only if C∆ < 0. If C∆ > 0, we have an imaginary ellipse, and if ∆ = 0, we have a point ellipse.[16]:p.63

The general equation's coefficients can be obtained from known semi-major axis a{displaystyle a}

- A=a2(sinΘ)2+b2(cosΘ)2B=2(b2−a2)sinΘcosΘC=a2(cosΘ)2+b2(sinΘ)2D=−2Axc−BycE=−Bxc−2CycF=Axc2+Bxcyc+Cyc2−a2b2{displaystyle {begin{aligned}A&=a^{2}(sin Theta )^{2}+b^{2}(cos Theta )^{2}\B&=2(b^{2}-a^{2})sin Theta cos Theta \C&=a^{2}(cos Theta )^{2}+b^{2}(sin Theta )^{2}\D&=-2Ax_{c}-By_{c}\E&=-Bx_{c}-2Cy_{c}\F&=Ax_{c}^{2}+Bx_{c}y_{c}+Cy_{c}^{2}-a^{2}b^{2}end{aligned}}}

These expressions can be derived from the canonical equation (see next section) by substituting the coordinates with expressions for rotation and translation of the coordinate system:

- xcan2a2+ycan2b2=1{displaystyle {frac {x_{can}^{2}}{a^{2}}}+{frac {y_{can}^{2}}{b^{2}}}=1}

- xcan=(x−xc)cosΘ+(y−yc)sinΘ{displaystyle x_{can}=(x-x_{c})cos Theta +(y-y_{c})sin Theta }

- ycan=−(x−xc)sinΘ+(y−yc)cosΘ{displaystyle y_{can}=-(x-x_{c})sin Theta +(y-y_{c})cos Theta }

Canonical form

Let a>b{displaystyle a>b}

- x2a2+y2b2=1{displaystyle {frac {x^{2}}{a^{2}}}+{frac {y^{2}}{b^{2}}}=1}

Here (x,y){displaystyle (x,y)}

In this system, the center is the origin (0,0){displaystyle (0,0)}

Any ellipse can be obtained by rotation and translation of a canonical ellipse with the proper semi-diameters. The expression of an ellipse centered at (Xc,Yc){displaystyle (X_{c},Y_{c})}

- (x−Xc)2a2+(y−Yc)2b2=1{displaystyle {frac {(x-X_{c})^{2}}{a^{2}}}+{frac {(y-Y_{c})^{2}}{b^{2}}}=1}

Moreover, any canonical ellipse can be obtained by scaling the unit circle of R2{displaystyle mathbb {R} ^{2}}

- X2+Y2=1{displaystyle X^{2}+Y^{2}=1,}

by factors a and b along the two axes.

For an ellipse in canonical form, we have

- Y=±b1−(X/a)2=±(a2−X2)(1−e2){displaystyle Y=pm b{sqrt {1-(X/a)^{2}}}=pm {sqrt {(a^{2}-X^{2})(1-e^{2})}}}

The distances from a point (X,Y){displaystyle (X,Y)}

The canonical form coefficients can be obtained from the general form coefficients using the following equations:

- a,b=−2(AE2+CD2−BDE+(B2−4AC)F)(A+C±(A−C)2+B2)B2−4ACXc=2CD−BEB2−4ACYc=2AE−BDB2−4ACΘ={0for B=0,A<C90∘for B=0,A>CarctanC−A−(A−C)2+B2Bfor B≠0{displaystyle {begin{aligned}a,b&={frac {-{sqrt {2{Big (}AE^{2}+CD^{2}-BDE+(B^{2}-4AC)F{Big )}left(A+Cpm {sqrt {(A-C)^{2}+B^{2}}}right)}}}{B^{2}-4AC}}\X_{c}&={frac {2CD-BE}{B^{2}-4AC}}\Y_{c}&={frac {2AE-BD}{B^{2}-4AC}}\Theta &={begin{cases}0&{text{for }}B=0,A<C\90^{circ }&{text{for }}B=0,A>C\arctan {frac {C-A-{sqrt {(A-C)^{2}+B^{2}}}}{B}}&{text{for }}Bneq 0end{cases}}end{aligned}}}

where Θ{displaystyle Theta }

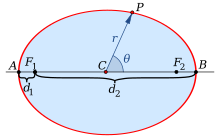

Polar forms

Polar form relative to center

Polar coordinates centered at the center

In polar coordinates, with the origin at the center of the ellipse and with the angular coordinate θ{displaystyle theta }

- r(θ)=ab(bcosθ)2+(asinθ)2=b1−(ecosθ)2{displaystyle r(theta )={frac {ab}{sqrt {(bcos theta )^{2}+(asin theta )^{2}}}}={frac {b}{sqrt {1-(ecos theta )^{2}}}}}

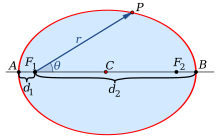

Polar form relative to focus

Polar coordinates centered at focus

If instead we use polar coordinates with the origin at one focus, with the angular coordinate θ=0{displaystyle theta =0}

- r(θ)=a(1−e2)1±ecosθ{displaystyle r(theta )={frac {a(1-e^{2})}{1pm ecos theta }}}

where the sign in the denominator is negative if the reference direction θ=0{displaystyle theta =0}

In the slightly more general case of an ellipse with one focus at the origin and the other focus at angular coordinate ϕ{displaystyle phi }

- r=a(1−e2)1−ecos(θ−ϕ).{displaystyle r={frac {a(1-e^{2})}{1-ecos(theta -phi )}}.}

The angle θ{displaystyle theta }

Ellipse as hypotrochoid

An ellipse (in red) as a special case of the hypotrochoid with R = 2r

The ellipse is a special case of the hypotrochoid when R = 2r, as shown in the adjacent image. The special case of a moving circle with radius r{displaystyle r}

Ellipses in triangle geometry

Ellipses appear in triangle geometry as

Steiner ellipse: ellipse through the vertices of the triangle with center at the centroid,

inellipses: ellipses which touch the sides of a triangle. Special cases are the Steiner inellipse and the Mandart inellipse.

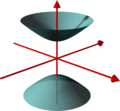

Ellipses as plane sections of quadrics

Ellipses appear as plane sections of the following quadrics:

- Ellipsoid

- Elliptic cone

- Elliptic cylinder

- Hyperboloid of one sheet

- Hyperboloid of two sheets

Ellipsoid

Elliptic cone

Elliptic cylinder

Hyperboloid of one sheet

Hyperboloid of two sheets

Applications

Physics

Elliptical reflectors and acoustics

If the water's surface is disturbed at one focus of an elliptical water tank, the circular waves of that disturbance, after reflecting off the walls, converge simultaneously to a single point: the second focus. This is a consequence of the total travel length being the same along any wall-bouncing path between the two foci.

Similarly, if a light source is placed at one focus of an elliptic mirror, all light rays on the plane of the ellipse are reflected to the second focus. Since no other smooth curve has such a property, it can be used as an alternative definition of an ellipse. (In the special case of a circle with a source at its center all light would be reflected back to the center.) If the ellipse is rotated along its major axis to produce an ellipsoidal mirror (specifically, a prolate spheroid), this property holds for all rays out of the source. Alternatively, a cylindrical mirror with elliptical cross-section can be used to focus light from a linear fluorescent lamp along a line of the paper; such mirrors are used in some document scanners.

Sound waves are reflected in a similar way, so in a large elliptical room a person standing at one focus can hear a person standing at the other focus remarkably well. The effect is even more evident under a vaulted roof shaped as a section of a prolate spheroid. Such a room is called a whisper chamber. The same effect can be demonstrated with two reflectors shaped like the end caps of such a spheroid, placed facing each other at the proper distance. Examples are the National Statuary Hall at the United States Capitol (where John Quincy Adams is said to have used this property for eavesdropping on political matters); the Mormon Tabernacle at Temple Square in Salt Lake City, Utah; at an exhibit on sound at the Museum of Science and Industry in Chicago; in front of the University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign Foellinger Auditorium; and also at a side chamber of the Palace of Charles V, in the Alhambra.

Planetary orbits

In the 17th century, Johannes Kepler discovered that the orbits along which the planets travel around the Sun are ellipses with the Sun [approximately] at one focus, in his first law of planetary motion. Later, Isaac Newton explained this as a corollary of his law of universal gravitation.

More generally, in the gravitational two-body problem, if the two bodies are bound to each other (that is, the total energy is negative), their orbits are similar ellipses with the common barycenter being one of the foci of each ellipse. The other focus of either ellipse has no known physical significance. The orbit of either body in the reference frame of the other is also an ellipse, with the other body at the same focus.

Keplerian elliptical orbits are the result of any radially directed attraction force whose strength is inversely proportional to the square of the distance. Thus, in principle, the motion of two oppositely charged particles in empty space would also be an ellipse. (However, this conclusion ignores losses due to electromagnetic radiation and quantum effects, which become significant when the particles are moving at high speed.)

For elliptical orbits, useful relations involving the eccentricity e{displaystyle e}

- e=ra−rpra+rp=ra−rp2ara=(1+e)arp=(1−e)a{displaystyle {begin{aligned}e&={frac {r_{a}-r_{p}}{r_{a}+r_{p}}}={frac {r_{a}-r_{p}}{2a}}\r_{a}&=(1+e)a\r_{p}&=(1-e)aend{aligned}}}

where

ra{displaystyle r_{a}}is the radius at apoapsis (the farthest distance)

rp{displaystyle r_{p}}is the radius at periapsis (the closest distance)

a{displaystyle a}is the length of the semi-major axis

Also, in terms of ra{displaystyle r_{a}}

a=ra+rp2b=ra⋅rpl=21ra+1rp=2rarpra+rp{displaystyle {begin{aligned}a&={frac {r_{a}+r_{p}}{2}}\b&={sqrt {r_{a}cdot r_{p}}}\l&={frac {2}{{frac {1}{r_{a}}}+{frac {1}{r_{p}}}}}={frac {2r_{a}r_{p}}{r_{a}+r_{p}}}end{aligned}}}.

Harmonic oscillators

The general solution for a harmonic oscillator in two or more dimensions is also an ellipse. Such is the case, for instance, of a long pendulum that is free to move in two dimensions; of a mass attached to a fixed point by a perfectly elastic spring; or of any object that moves under influence of an attractive force that is directly proportional to its distance from a fixed attractor. Unlike Keplerian orbits, however, these "harmonic orbits" have the center of attraction at the geometric center of the ellipse, and have fairly simple equations of motion.

Phase visualization

In electronics, the relative phase of two sinusoidal signals can be compared by feeding them to the vertical and horizontal inputs of an oscilloscope. If the display is an ellipse, rather than a straight line, the two signals are out of phase.

Elliptical gears

Two non-circular gears with the same elliptical outline, each pivoting around one focus and positioned at the proper angle, turn smoothly while maintaining contact at all times. Alternatively, they can be connected by a link chain or timing belt, or in the case of a bicycle the main chainring may be elliptical, or an ovoid similar to an ellipse in form. Such elliptical gears may be used in mechanical equipment to produce variable angular speed or torque from a constant rotation of the driving axle, or in the case of a bicycle to allow a varying crank rotation speed with inversely varying mechanical advantage.

Elliptical bicycle gears make it easier for the chain to slide off the cog when changing gears.[17]

An example gear application would be a device that winds thread onto a conical bobbin on a spinning machine. The bobbin would need to wind faster when the thread is near the apex than when it is near the base.[18]

Optics

- In a material that is optically anisotropic (birefringent), the refractive index depends on the direction of the light. The dependency can be described by an index ellipsoid. (If the material is optically isotropic, this ellipsoid is a sphere.)

- In lamp-pumped solid-state lasers, elliptical cylinder-shaped reflectors have been used to direct light from the pump lamp (coaxial with one ellipse focal axis) to the active medium rod (coaxial with the second focal axis).[19]

- In laser-plasma produced EUV light sources used in microchip lithography, EUV light is generated by plasma positioned in the primary focus of an ellipsoid mirror and is collected in the secondary focus at the input of the lithography machine.[20]

Statistics and finance

In statistics, a bivariate random vector (X, Y) is jointly elliptically distributed if its iso-density contours—loci of equal values of the density function—are ellipses. The concept extends to an arbitrary number of elements of the random vector, in which case in general the iso-density contours are ellipsoids. A special case is the multivariate normal distribution. The elliptical distributions are important in finance because if rates of return on assets are jointly elliptically distributed then all portfolios can be characterized completely by their mean and variance—that is, any two portfolios with identical mean and variance of portfolio return have identical distributions of portfolio return.[21][22]

Computer graphics

Drawing an ellipse as a graphics primitive is common in standard display libraries, such as the MacIntosh QuickDraw API, and Direct2D on Windows. Jack Bresenham at IBM is most famous for the invention of 2D drawing primitives, including line and circle drawing, using only fast integer operations such as addition and branch on carry bit. M. L. V. Pitteway extended Bresenham's algorithm for lines to conics in 1967.[23] Another efficient generalization to draw ellipses was invented in 1984 by Jerry Van Aken.[24]

In 1970 Danny Cohen presented at the "Computer Graphics 1970" conference in England a linear algorithm for drawing ellipses and circles. In 1971, L. B. Smith published similar algorithms for all conic sections and proved them to have good properties.[25] These algorithms need only a few multiplications and additions to calculate each vector.

It is beneficial to use a parametric formulation in computer graphics because the density of points is greatest where there is the most curvature. Thus, the change in slope between each successive point is small, reducing the apparent "jaggedness" of the approximation.

- Drawing with Bézier paths

Composite Bézier curves may also be used to draw an ellipse to sufficient accuracy, since any ellipse may be construed as an affine transformation of a circle. The spline methods used to draw a circle may be used to draw an ellipse, since the constituent Bézier curves behave appropriately under such transformations.

Optimization theory

It is sometimes useful to find the minimum bounding ellipse on a set of points. The ellipsoid method is quite useful for attacking this problem.

See also

Apollonius of Perga, the classical authority

Cartesian oval, a generalization of the ellipse- Circumconic and inconic

- Conic section

- Ellipse fitting

Ellipsoid, a higher dimensional analog of an ellipse

Elliptic coordinates, an orthogonal coordinate system based on families of ellipses and hyperbolae

- Elliptic partial differential equation

Elliptical distribution, in statistics- Geodesics on an ellipsoid

- Great ellipse

- Hyperbola

- Kepler's laws of planetary motion

- Matrix representation of conic sections

n-ellipse, a generalization of the ellipse for n foci- Oval

- Parabola

Rytz’s construction, a method for finding the ellipse axes from conjugate diameters or a parallelogram

Spheroid, the ellipsoid obtained by rotating an ellipse about its major or minor axis

Stadium (geometry), a two-dimensional geometric shape constructed of a rectangle with semicircles at a pair of opposite sides

Steiner circumellipse, the unique ellipse circumscribing a triangle and sharing its centroid

Steiner inellipse, the unique ellipse inscribed in a triangle with tangencies at the sides' midpoints

Superellipse, a generalization of an ellipse that can look more rectangular or more "pointy"

True, eccentric, and mean anomaly

Notes

^ Apostol, Tom M.; Mnatsakanian, Mamikon A. (2012), New Horizons in Geometry, The Dolciani Mathematical Expositions #47, The Mathematical Association of America, p. 251, ISBN 978-0-88385-354-2.mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ The German term for this circle is Leitkreis which can be translated as "Director circle", but that term has a different meaning in the English literature (see Director circle).

^ K. Strubecker: Vorlesungen über Darstellende Geometrie, GÖTTINGEN,

VANDENHOECK & RUPRECHT, 1967, p. 26

^ K. Strubecker: Vorlesungen über Darstellende Geometrie. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1967, S. 26.

^ J. van Mannen: Seventeenth century instruments for drawing conic sections. In: The Mathematical Gazette. Vol. 76, 1992, p. 222–230.

^ E. Hartmann: Lecture Note 'Planar Circle Geometries', an Introduction to Möbius-, Laguerre- and Minkowski Planes, p. 55

^ W. Benz, Vorlesungen über Geomerie der Algebren, Springer (1973)

^ Carlson, B. C. (2010), "Elliptic Integrals", in Olver, Frank W. J.; Lozier, Daniel M.; Boisvert, Ronald F.; Clark, Charles W., NIST Handbook of Mathematical Functions, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0521192255, MR 2723248

^ Python code for the circumference of an ellipse in terms of the complete elliptic integral of the second kind, retrieved 2013-12-28

^ Ivory, J. (1798). "A new series for the rectification of the ellipsis". Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh. 4 (2): 177–190. doi:10.1017/s0080456800030817.

^ Bessel, F. W. (2010). "The calculation of longitude and latitude from geodesic measurements (1825)". Astron. Nachr. 331 (8): 852–861. arXiv:0908.1824. Bibcode:2010AN....331..852K. doi:10.1002/asna.201011352. Englisch translation of Bessel, F. W. (1825). "Über die Berechnung der geographischen Längen und Breiten aus geodätischen Vermesssungen". Astron. Nachr. 4 (16): 241–254. arXiv:0908.1823. Bibcode:1825AN......4..241B. doi:10.1002/asna.18260041601.

^ Ramanujan, Srinivasa (1914). "Modular Equations and Approximations to π". Quart. J. Pure App. Math. 45: 350–372. ISBN 9780821820766.

^ Jameson, G.J.O. (2014). "Inequalities for the perimeter of an ellipse". Mathematical Gazette. 98 (542): 227–234. doi:10.1017/S002555720000125X.

^ Larson, Ron; Hostetler, Robert P.; Falvo, David C. (2006). "Chapter 10". Precalculus with Limits. Cengage Learning. p. 767. ISBN 978-0-618-66089-6.

^ Young, Cynthia Y. (2010). "Chapter 9". Precalculus. John Wiley and Sons. p. 831. ISBN 978-0-471-75684-2.

^ ab Lawrence, J. Dennis, A Catalog of Special Plane Curves, Dover Publ., 1972.

^ David Drew.

"Elliptical Gears".

[1]

^ Grant, George B. (1906). A treatise on gear wheels. Philadelphia Gear Works. p. 72.

^ Encyclopedia of Laser Physics and Technology - lamp-pumped lasers, arc lamps, flash lamps, high-power, Nd:YAG laser

^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2013-05-17. Retrieved 2013-06-20.CS1 maint: Archived copy as title (link)

^ Chamberlain, G. (February 1983). "A characterization of the distributions that imply mean—Variance utility functions". Journal of Economic Theory. 29 (1): 185–201. doi:10.1016/0022-0531(83)90129-1.

^ Owen, J.; Rabinovitch, R. (June 1983). "On the class of elliptical distributions and their applications to the theory of portfolio choice". Journal of Finance. 38 (3): 745–752. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6261.1983.tb02499.x. JSTOR 2328079.

^ Pitteway, M.L.V. (1967). "Algorithm for drawing ellipses or hyperbolae with a digital plotter". The Computer Journal. 10 (3): 282–9. doi:10.1093/comjnl/10.3.282.

^ Van Aken, J.R. (September 1984). "An Efficient Ellipse-Drawing Algorithm". IEEE Computer Graphics and Applications. 4 (9): 24–35. doi:10.1109/MCG.1984.275994.

^ Smith, L.B. (1971). "Drawing ellipses, hyperbolae or parabolae with a fixed number of points". The Computer Journal. 14 (1): 81–86. doi:10.1093/comjnl/14.1.81.

References

Besant, W.H. (1907). "Chapter III. The Ellipse". Conic Sections. London: George Bell and Sons. p. 50.

Coxeter, H.S.M. (1969). Introduction to Geometry (2nd ed.). New York: Wiley. pp. 115–9.

Meserve, Bruce E. (1983) [1959], Fundamental Concepts of Geometry, Dover, ISBN 978-0-486-63415-9

Miller, Charles D.; Lial, Margaret L.; Schneider, David I. (1990). Fundamentals of College Algebra (3rd ed.). Scott Foresman/Little. p. 381. ISBN 978-0-673-38638-0.

External links

Quotations related to Ellipse at Wikiquote

Quotations related to Ellipse at Wikiquote

Media related to Ellipses at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Ellipses at Wikimedia Commons

Ellipse (mathematics) at Encyclopædia Britannica

ellipse at PlanetMath.org.- Weisstein, Eric W. "Ellipse". MathWorld.

- Weisstein, Eric W. "Ellipse as special case of hypotrochoid". MathWorld.

Apollonius' Derivation of the Ellipse at Convergence

The Shape and History of The Ellipse in Washington, D.C. by Clark Kimberling

- Ellipse circumference calculator

- Collection of animated ellipse demonstrations

Ivanov, A.B. (2001) [1994], "Ellipse", in Hazewinkel, Michiel, Encyclopedia of Mathematics, Springer Science+Business Media B.V. / Kluwer Academic Publishers, ISBN 978-1-55608-010-4

- Trammel according Frans van Schooten

![{displaystyle C=2pi aleft[{1-left({frac {1}{2}}right)^{2}e^{2}-left({frac {1cdot 3}{2cdot 4}}right)^{2}{frac {e^{4}}{3}}-left({frac {1cdot 3cdot 5}{2cdot 4cdot 6}}right)^{2}{frac {e^{6}}{5}}-cdots }right]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/e501b8ef0a491a04ec372b008ed41e0298acfa41)

![{displaystyle =2pi aleft[1-sum _{n=1}^{infty }left({frac {(2n-1)!!}{(2n)!!}}right)^{2}{frac {e^{2n}}{2n-1}}right],}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/d2b0f06eb6428d757cfd44979342db46bad93448)

![{displaystyle C=pi (a+b)left[1+sum _{n=1}^{infty }left({frac {(2n-1)!!}{2^{n}n!}}right)^{2}{frac {h^{n}}{(2n-1)^{2}}}right].}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/bbdc893aa9afd300340de4f2a6ed6b39a3ac81d3)

![Capprox pi left[3(a+b)-{sqrt {(3a+b)(a+3b)}}right]=pi left[3(a+b)-{sqrt {10ab+3(a^{2}+b^{2})}}right]](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/38b3f790cb11678c0ed8bcba9d0ba2660ca42339)