Diatonic scale

In western music theory, a diatonic scale is a heptatonic scale that includes five whole steps (whole tones) and two half steps (semitones) in each octave, in which the two half steps are separated from each other by either two or three whole steps, depending on their position in the scale. This pattern ensures that, in a diatonic scale spanning more than one octave, all the half steps are maximally separated from each other (i.e. separated by at least two whole steps).

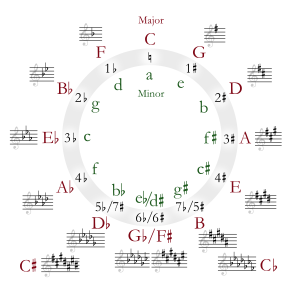

The seven pitches of any diatonic scale can also be obtained by using a chain of six perfect fifths. For instance, the seven natural pitches that form the C-major scale can be obtained from a stack of perfect fifths starting from F:

- F—C—G—D—A—E—B

Any sequence of seven successive natural notes, such as C–D–E–F–G–A–B, and any transposition thereof, is a diatonic scale. Modern musical keyboards are designed so that the white notes form a diatonic scale, though transpositions of this diatonic scale require one or more black keys. A diatonic scale can be also described as two tetrachords separated by a whole tone.

The term diatonic originally referred to the diatonic genus, one of the three genera of the ancient Greeks. In musical set theory, Allen Forte classifies diatonic scales as set form 7–35.

This article does not concern alternative seven-note diatonic scales such as the harmonic minor or the melodic minor.

Contents

1 History

1.1 Prehistory

1.2 Middle Ages

1.3 Renaissance

1.4 Modern

2 Theory

2.1 Major scale

2.2 Natural minor scale

2.3 Modes

2.4 Diatonic scales and tetrachords

3 Properties

4 Tuning

4.1 Iteration of the fifth

4.1.1 Pythagorean tuning

4.1.2 Equal temperament

4.1.3 Meantone temperament

4.2 Just intonation

5 See also

6 References

7 Further reading

8 External links

History

Western music from the Middle Ages until the late 19th century (see common practice period) is based on the diatonic scale and the unique hierarchical relationships created by this system of organizing seven notes.

Prehistory

There is one claim that the 45,000-year-old Divje Babe Flute uses a diatonic scale, but there is no proof or consensus it is even a musical instrument.[1]

There is evidence that the Sumerians and Babylonians used some version of the diatonic scale.[2][3] This derives from surviving inscriptions that contain a tuning system and musical composition. Despite the conjectural nature of reconstructions of the piece known as the Hurrian songs from the surviving score, the evidence that it used the diatonic scale is much more soundly based. This is because instructions for tuning the scale involve tuning a chain of six fifths, so that the corresponding circle of seven major and minor thirds are all consonant-sounding, and this is a recipe for tuning a diatonic scale.

9,000-year-old flutes found in Jiahu, China indicate the evolution, over a period of 1,200 years, of flutes having 4, 5 and 6 holes to having 7 and 8 holes, the latter exhibiting striking similarity to diatonic hole spacings and sounds.[4]

Middle Ages

The scales corresponding to the medieval church modes were diatonic. Depending on which of the seven notes of the diatonic scale you use as the beginning, the positions of the intervals fall at different distances from the starting tone (the "reference note"), producing seven different scales. One of these, the one starting on B, has no pure fifth above its reference note (B–F is a diminished fifth): it is probably for this reason that it was not used. Of the six remaining scales, two were described as corresponding to two others with a B♭ instead of a B♮:

- A–B–C–D–E–F–G–A was described as D–E–F–G–A–B♭–C–D (the modern A and D Aeolian scales, respectively)

- C–D–E–F–G–A–B–C was described as F–G–A–B♭–C–D–E–F (the modern C and F Ionian (major) scales, respectively)

As a result, medieval theory described the church modes as corresponding to four diatonic scales only (two of which had the variable B♮/♭).

Renaissance

Heinrich Glarean considered that the modal scales including a B♭ had to be the result of a transposition. In his Dodecachordon, he not only described six "natural" diatonic scales (still neglecting the seventh one with a diminished fifth above the reference note), but also six "transposed" ones, each including a B♭, resulting in the total of twelve scales that justified the title of his treatise.

Modern

By the beginning of the Baroque period, the notion of musical key was established, describing additional possible transpositions of the diatonic scale. Major and minor scales came to dominate until at least the start of the 20th century, partly because their intervallic patterns are suited to the reinforcement of a central triad. Some church modes survived into the early 18th century, as well as appearing in classical and 20th-century music, and jazz (see chord-scale system).

Theory

The modern piano keyboard is based on the interval patterns of the diatonic scale. Any sequence of seven successive white keys plays a diatonic scale.

Of Glarean's six natural scales, three are major scales (those with a major third/triad: Ionian, Lydian, and Mixolydian), three are minor (those with a minor third/triad: Dorian, Phrygian, and Aeolian). To these may be added the seventh diatonic scale, with a diminished fifth above the reference note, the Locrian scale. These could be transposed not only to include one flat in the signature (as described by Glarean), but to all twelve notes of the chromatic scale, resulting in a total of eighty-four diatonic scales.

The modern musical keyboard originated as a diatonic keyboard with only white keys.[5] The black keys were progressively added for several purposes:

- improving the consonances, mainly the thirds, by providing a major third on each degree;

- allowing all twelve transpositions described above;

- and helping musicians to find their bearings on the keyboard.[citation needed]

The pattern of elementary intervals forming the diatonic scale can be represented either by the letters T (Tone) and S (Semitone) respectively. With this abbreviation, major scale, for instance, can be represented as

- T–T–S–T–T–T–S

Major scale

The major scale or Ionian scale is one of the diatonic scales. It is made up of seven distinct notes, plus an eighth that duplicates the first an octave higher. The pattern of seven intervals separating the eight notes is T–T–S–T–T–T–S. In solfege, the syllables used to name each degree of the scale are Do–Re–Mi–Fa–Sol–La–Ti–Do. A sequence of successive natural notes starting from C is an example of major scale, called C-major scale.

| Notes in C major: | C | D | E | F | G | A | B | C | ||||||||

| Degrees in solfege: | Do | Re | Mi | Fa | Sol | La | Ti | Do | ||||||||

| Interval sequence: | T | T | S | T | T | T | S | |

The eight degrees of the scale are also known by traditional names, especially when used in a tonal context:

- 1st – Tonic (key note)

- 2nd – Supertonic

- 3rd – Mediant

- 4th – Subdominant

- 5th – Dominant

- 6th – Submediant

- 7th – Leading tone

- 8th – Tonic (Octave)

Natural minor scale

For each major scale, there is a corresponding natural minor scale, sometimes called its relative minor. It uses the same sequence of notes as the corresponding major scale but starts from a different note. That is, it begins on the sixth degree of the major scale and proceeds step-by-step to the first octave of the sixth degree. A sequence of successive natural notes starting from A is an example of a natural minor scale, called the A natural minor scale.

| Notes in A minor: | A | B | C | D | E | F | G | A | ||||||||

| Interval sequence: | T | S | T | T | S | T | T | |

The degrees of the natural minor scale, especially in a tonal context, have the same names as those of the major scale, except the seventh degree, which is known as the subtonic because it is a whole step below the tonic. The term leading tone is generally reserved for seventh degrees that are a half step (semitone) below the tonic, as is the case in the major scale.

Besides the natural minor scale, five other kinds of scales can be obtained from the notes of a major scale, by simply choosing a different note as the starting note. All these scales meet the definition of diatonic scale.

Modes

The whole collection of diatonic scales as defined above can be divided into seven different scales.

As explained above, all major scales use the same interval sequence T–T–S–T–T–T–S. This interval sequence was called the Ionian mode by Glarean. It is one of the seven modern modes. From any major scale, a new scale is obtained by taking a different degree as the tonic. With this method it is possible to generate six other scales or modes from each major scale. Another way to describe the same result would be to consider that, behind the diatonic scales, there exists an underlying "diatonic system" which is the series of diatonic notes without a reference note; assigning the reference note in turn to each of the seven notes in each octave of the system produces seven diatonic scales, each characterized by a different interval sequence:

| Mode | Also known as | Starting note relative to major scale | Interval sequence | Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ionian | Major scale | I | T–T–S–T–T–T–S | C–D–E–F–G–A–B–C |

| Dorian | II | T–S–T–T–T–S–T | D–E–F–G–A–B–C–D | |

| Phrygian | III | S–T–T–T–S–T–T | E–F–G–A–B–C–D–E | |

| Lydian | IV | T–T–T–S–T–T–S | F–G–A–B–C–D–E–F | |

| Mixolydian | V | T–T–S–T–T–S–T | G–A–B–C–D–E–F–G | |

| Aeolian | Natural minor scale | VI | T–S–T–T–S–T–T | A–B–C–D–E–F–G–A |

| Locrian | VII | S–T–T–S–T–T–T | B–C–D–E–F–G–A–B |

For the sake of simplicity, the examples shown above are formed by natural notes (i.e. neither sharps nor flats, also called "white-notes", as they can be played using the white keys of a piano keyboard). However, any transposition of each of these scales (or of the system underlying them) is a valid example of the corresponding mode. In other words, transposition preserves mode.

The whole set of diatonic scales is commonly defined as the set composed of these seven natural-note scales, together with all of their possible transpositions. As discussed elsewhere, different definitions of this set are sometimes adopted in the literature.

Pitch constellations of the modern musical modes

Diatonic scales and tetrachords

A diatonic scale can be also described as two tetrachords separated by a whole tone. For example, under this view the two tetrachord structures of C major would be:

- [C–D–E–F] – [G–A–B–C]

and the natural minor of A would be:

- [A–B–C–D] – [E–F–G–A].

The set of intervals within each tetrachord comprises two tones and a semitone.

Properties

The diatonic scale as defined above has specific properties that make it unique among seven-note scales. Many of these properties are embedded in Western musical theory and notation, which were conceived at a time when Western music was mainly diatonic. These properties include:

- The diatonic scale is obtained from a chain of six successive fifths. For instance, the seven natural pitches that form the C-major scale can be obtained from a chain of fifths starting from F (F—C—G—D—A—E—B).

- It is either a sequence of successive natural notes (such as the C-major scale, C–D–E–F–G–A–B, or the A-minor scale, A–B–C–D–E–F–G) or a transposition thereof.

- It can be written using seven consecutive notes without accidentals on a staff with no key signature or, when transposed, with a conventional key signature or with accidentals.

David Rothenberg generalized properties of the diatonic scale to other scales in what he called "propriety": see Rothenberg propriety. Around the same time Gerald Balzano independently came up with the same definition in the more limited context of equal temperaments, calling it "coherence". The generation of the diatonic scale by iterations of a single generator, the fifth, has also been generalized by Erv Wilson, in what is sometimes called a MOS scale. See also Diatonic set theory for a discussion of other properties that transcend the diatonic scale properly speaking.

Tuning

Diatonic scales can be tuned variously, either by iteration of a perfect or tempered fifth, or by a combination of perfect fifths and perfect thirds (Just intonation), or possibly by a combination of fifths and thirds of various sizes, as in well temperament.

Iteration of the fifth

Pythagorean tuning

If the scale is produced by the iteration of six perfect fifths, for instance F–C–G–D–A–E–B, the result is Pythagorean tuning:

| note | F | C | G | D | A | E | B | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pitch | 2⁄3 | 1⁄1 | 3⁄2 | 9⁄4 | 27⁄8 | 81⁄16 | 243⁄32 | |

| bring into main octave | 4⁄3 | 1⁄1 | 3⁄2 | 9⁄8 | 27⁄16 | 81⁄64 | 243⁄128 | |

| sort into note order | C | D | E | F | G | A | B | C' |

| interval above C | 1⁄1 | 9⁄8 | 81⁄64 | 4⁄3 | 3⁄2 | 27⁄16 | 243⁄128 | 2⁄1 |

| interval between notes | 9⁄8 | 9⁄8 | 256⁄243 | 9⁄8 | 9⁄8 | 9⁄8 | 256⁄243 |

Six of the "fifth" intervals (C–G, D–A, E–B, F–C', G–D', A–E') are all 3⁄2 = 1.5, but B–F' is the discordant tritone, here 729⁄512 ≈ 1.423828125.

Extending the series of fifths to eleven fifths would result into the Pythagorean Chromatic scale. It would add pitches for the five "piano black key" notes, for instance A♭–E♭–B♭–F–C–G–D–A–E–B–F♯–C♯–G♯. A♭ and G♯ are commonly thought of as being the same note, but as worked out in this way, G♯ is higher pitch than A♭ by about 1.01364 (1.512⁄128, the Pythagorean comma, about 24% of a semitone, 312⁄219 = 531,441⁄524,288). Depending on whether one chooses A♭ or G♯, one would convert one of the perfect fifths into a dissonant chord called a wolf fifth, either C♯–A♭ or G♯–E♭, a Pythagorean comma narrower than a perfect fifth.

Equal temperament

To cure this and other effects, in the modern twelve-tone equal temperament as used for pianos and other instruments, the fifths are "tempered" by 1⁄12 of a Pythagorean comma each, so that the last fifth is the same as the previous ones. The frequency ratio of the semitone then becomes the twelfth root of two (12√2 ≈ 1.059463). If S, the ratio of the semitone, is 12√2, the ratios for the other intervals become:

| notes | C | D | E | F | G | A | B | C' |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pitch | 1 | S2 | S4 | S5 | S7 | S9 | S11 | S12 |

| interval between notes | S2 | S2 | S | S2 | S2 | S2 | S |

with the exponents denoting the number of semitones. The (tempered) fifth intervals (C–G, D–A, E–B; F–C'; G–D'; A–E') are all S7 ≈ 1.4983, i.e. made of 7 (tempered) semitones, but B–F' (the tritone) is S6 = √2 (about 1.4142, 6 semitones).

Meantone temperament

The fifths could be tempered more than in equal temperament, in order to produce better thirds. See quarter-comma meantone for a meantone temperament commonly used in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries and sometimes after, which produces perfect major thirds.

Just intonation

Just intonation often is represented using Euler's Tonnetz, with the horizontal axis showing the perfect fifths and the vertical axis the perfect major thirds. In the Tonnetz, the diatonic scale in just intonation appears as follows:

| A | E | B | |

| F | C | G | D |

F–A, C–E and G–B, aligned vertically, are perfect major thirds; A–E–B and F–C–G–D are two series of perfect fifths. The notes of the top line, A, E and B, are lowered by the syntonic comma, 81⁄80, and the "wolf" fifth D–A is too narrow by the same amount. The tritone F–B is 45⁄32 ≈ 1.40625.

This tuning has been first described by Ptolemy and is known as Ptolemy's intense diatonic scale. It was also mentioned by Zarlino in the 16th century and has been described by theorists in the 17th and 18th centuries as the "natural" scale.

| notes | C | D | E | F | G | A | B | C' |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pitch | 1⁄1 | 9⁄8 | 5⁄4 | 4⁄3 | 3⁄2 | 5⁄3 | 15⁄8 | 2⁄1 |

| interval between notes | 9⁄8 | 10⁄9 | 16⁄15 | 9⁄8 | 10⁄9 | 9⁄8 | 16⁄15 |

Since the frequency ratios are based on simple powers of the prime numbers 2,3 and 5 this is also known as Five-limit tuning.

See also

- Circle of fifths text table

- Piano key frequencies

- History of music

- Prehistoric music

- Musical acoustics

Jiahu: A place in central China where the oldest (Neolithic) still-playable flute was found.- Diatonic and chromatic

References

^ "Random Samples", Science April 1997, vol 276 no 5310 pp 203–205 (available online).

^ Kilmer, Anne Draffkorn (1998). "The Musical Instruments from Ur and Ancient Mesopotamian Music". Expedition Magazine. 40 (2): 12–19. Retrieved 2015-12-29..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ Crickmore, Leon (2010). "New Light on the Babylonian Tonal System" (PDF). In Dumbrill, Richard; Finkel, Irving. ICONEA 2008: Proceedings of the International Conference of Near Eastern Archaeomusicology. 24. London: Iconea Publications. pp. 11–22. Retrieved 2015-12-29.

^ Zhang, Juzhong; Harbottle, Garman; Wang, Changsui; Kong, Zhaochen (23 September 1999). "Oldest playable musical instruments found at Jiahu early Neolithic site in China". Nature. 401 (6751): 366–368. doi:10.1038/43865. PMID 16862110.

^ Meeùs, N. (2001). Keyboard. Grove Music Online. Retrieved 9 May. 2018, from http://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/grovemusic/view/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.001.0001/omo-9781561592630-e-0000014944.

Further reading

- Balzano, Gerald J. (1980). "The Group Theoretic Description of 12-fold and Microtonal Pitch Systems", Computer Music Journal 4:66–84.

- Balzano, Gerald J. (1982). "The Pitch Set as a Level of Description for Studying Musical Pitch Perception", Music, Mind, and Brain, Manfred Clynes, ed., Plenum press.

- Clough, John (1979). "Aspects of Diatonic Sets", Journal of Music Theory 23:45–61.

- Ellen Hickmann, Anne D. Kilmer and Ricardo Eichmann, (ed.) Studies in Music Archaeology III, 2001, VML Verlag Marie Leidorf GmbH., Germany

ISBN 3-89646-640-2. - Franklin, John C. (2002). "Diatonic Music in Greece: a Reassessment of its Antiquity", Mnemosyne 56.1:669–702

- Gould, Mark (2000). "Balzano and Zweifel: Another Look at Generalised Diatonic Scales", "Perspectives of New Music" 38/2:88–105

- Johnson, Timothy (2003). Foundations Of Diatonic Theory: A Mathematically Based Approach to Music Fundamentals. Key College Publishing.

ISBN 1-930190-80-8. - Kilmer, A.D. (1971) "The Discovery of an Ancient Mesopotamian Theory of Music'". Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 115:131–149.

- Kilmer, Crocket, Brown: Sounds from Silence 1976, Bit Enki Publications, Berkeley, Calif. LC# 76-16729.

- David Rothenberg (1978). "A Model for Pattern Perception with Musical Applications Part I: Pitch Structures as order-preserving maps", Mathematical Systems Theory 11:199–234

External links

Diatonic Scale on Eric Weisstein's Treasure trove of Music- The diatonic scale on the guitar

Diatonic scales and keys | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The table indicates the number of sharps or flats in each scale. Minor scales are written in lower case. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||