White Carniola

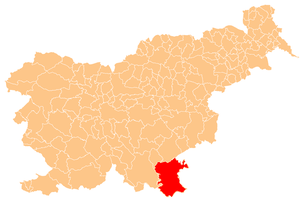

Location of White Carniola in Slovenia

White Carniola (Slovene: Bela krajina; German: Weißkrain or Weiße Mark) is a traditional region in southeastern Slovenia on the border with Croatia. Due to its smallness, it is often considered a subunit of the broader Lower Carniola region, although with distinctive cultural, linguistic, and historical features.[1]

Due to its proximity with Croatia, White Carniola shares many cultural and linguistic features with the neighboring Kajkavian Croatian areas. It is generally considered the Slovenian region with the closest cultural affinity with other South Slavic territories. It was part of Croatia until the 12th century, after which it shared the historical fate with the Windic March and Lower Carniola to the north. During the 19th century, it was one of the regions with the highest emigration rate in the Slovene Lands, and the Austrian Empire in general. During World War Two, it was an important center of anti-Fascist resistance in Slovenia.

Contents

1 Geography

2 Tradition

3 Name

4 History

4.1 Middle Ages

4.2 Early modern period

5 Buildings

5.1 Castles

6 Culture

7 Notable people

8 References

9 External links

Geography

Typical landscape in White Carniola

The area is confined by the Gorjanci and Kočevski Rog mountain ranges in the north and west and the Kolpa River in the south and east, which also forms part of the border between Slovenia and Croatia. As the area could only be reached from northern Lower Carniola by mountain passes, the inhabitants cultivate a certain distinctness.

The region corresponds to the present-day municipalities of Metlika, Črnomelj and Semič. The terrain is characterised by low karst hills and extended birch forests. The main river is the Kolpa with its Lahinja, Dobličica and Krupa tributaries.

White Carniola is known for Grič and Kanižarica pottery from clay with a distinct calcite content, as well as for high-quality wines, such as metliška črnina (a dark red wine), belokranjec (a white wine), and modra frankinja (i.e. Blaufränkisch).

Tradition

Peasants from White Carniola in traditional costumes at the beginning of the 20th century

A distinguishing part of White Carniola is its folk heritage. It still has many folklore events, which show traditional local costumes, music, played on a regionally known instrument called tamburica, and a circle dance, called belokranjsko kolo. A distinctive feature is also the pisanica, a coloured Easter egg decorated in a characteristic manner using beeswax that is found nowhere else in Slovenia. Belokranjska pogača (White Carniola flatbread), a specific type of bread has recently been granted with the European Union's Traditional Speciality Guaranteed designation.[2]

Name

The name Bela krajina literally means 'White March'. The noun krajina or 'march' refers to a border territory organized for military defense.[3] The adjective bela 'white' may refer to the deciduous trees (especially birch trees) in the area in comparison to "black" (i.e. coniferous)[4] trees in the neighboring Kočevje area.[3] It may also be an old designation for 'west', referring to the western location of the region in comparison to the Croatian Military Frontier (Slovene: Vojna krajina).[3] Non-linguistic explanations connect the designation bela with the traditional white linen clothing of the population.[5][6] The English name "White Carniola" derives from the German designation Weißkrain[7], which is the result of a hypercorrection based on the adjective belokrajnski (understood as a dialect metathesis of *belokranjski)[3][8] (cf. also German Dürrenkrain,[9][10] English: Dry Carniola,[11][12][13] for Slovene Suha krajina, literally 'dry region').[8]

History

Middle Ages

In the early 12th century, the area was part of the disputed border region between the Windic March and the March of Carniola, established by the Holy Roman Empire in the northwest, and the Hungarian crown lands in the Kingdom of Croatia in the southeast. From about 1127 the local counts of Višnja Gora (Weichselberg) backed by the Sponheim margraves and the Salzburg archbishops crossed the Gorjanci mountains and marched against the Hungarian and Croatian forces, which they pushed beyond the Kolpa River down to Bregana.

The Counts of Weichselberg, descendants of Saint Hemma of Gurk, established the Imperial Weiße Mark ('White march') in the acquired territories. They established their residence at Metlika (Möttling), and therefore in contemporary sources their lands were also referred to as the County of Möttling. After the line became extinct in 1209, the possessions passed to the Carniolan margraves from the Bavarian House of Andechs, the Dukes of Merania, and were finally acquired for the House of Habsburg by Archduke Rudolf IV of Austria, who proclaimed himself Duke of Carniola in 1364.

Early modern period

With the Ottoman conquest of Serbian territories, groups of Serbs fled to the north or west; of the western migrational groups, some settled in White Carniola and Žumberak.[14] In September 1597, with the fall of Slatina, some 1,700 Uskoks with their wives and children settled in Carniola, bringing some 4,000 sheep with them.[15] The following year, with the conquest of Cernik, some 500 Uskok families settled in Carniola.[15] At the end of the 17th century, with the stagnation of Ottoman power due to European pressure during internal crisis, and Austrian advance far into Macedonia, Serbs armed themselves and joined the fight against the Ottomans; the Austrian retreat prompted another massive exodus of Serbs from the Ottoman territories in ca. 1690 (see Great Serb Migrations).[16]

Buildings

Castles

Ruins of Pobrežje Castle

Several castles were built in the border region, especially during the Ottoman Wars from the 15th century onwards, as in Črnomelj, Gradac and Vinica. The remains of the large fortress in Pobrežje were destroyed in World War II.

Culture

Based on surnames found in White Carniola, it may be concluded that their ancestors were Serbs and Croats.[17] In old folk poetry of White Carniola, Serbian hero Prince Marko is often mentioned, sung in "clean Shtokavian".[17] A small Serb community exists in White Carniola.[18]

Notable people

Notable people that were born or lived in White Carniola include:

Juro Adlešič (1884–1968), lawyer and politician, mayor of Ljubljana from 1935 to 1942

Draga Ahačič (born 1924), actress, film director, translator, and journalist

Andrej Bajuk (1943–2011), politician and economist

Joe Cerne (born 1942), American football player

Oton Gliha (1914–1999), Croatian painter

Miran Jarc (1900–1942), writer, poet, playwright, and essayist

Lojze Krakar (1926–1995), poet, translator, editor, literary historian, and essayist

Radko Polič (born 1942), actor

John Vertin (1844–1899), Catholic priest, Bishop of Marquette in the US state of Michigan from 1879 to 1899

Oton Župančič (1878–1949), poet, playwright, and translator

References

^ Ferenc, Tone. 1988. "Dolenjska." Enciklopedija Slovenije, vol. 2, pp. 287–298. Ljubljana: Mladinska knjiga, p. 287.

^ "Bela Krajina". Retrieved 26 August 2016..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ abcd Snoj, Marko. 2009. Etimološki slovar slovenskih zemljepisnih imen. Ljubljana: Modrijan and Založba ZRC, p. 55.

^ Snoj, Marko. 2009. Etimološki slovar slovenskih zemljepisnih imen. Ljubljana: Modrijan and Založba ZRC, p. 101.

^ Lah, Iva. 1928. "Župančičeva mladina." In: Albrecht, Fran (ed.)Jubilejni zbornik za petdesetletnico Otona Župančiča (pp. 85–90). Ljubljana: Tiskovna zadruga, p. 86.

^ Longley, Norm. 2007. The Rough Guide to Slovenia. London: Rough Guides, p. 233.

^ Copeland, Fanny S. 1931. "Slovene Folklore" Folklore: A Quarterly Review of Myth, Tradition, Institution & Custom 42(4): 405–446, p. 431.

^ ab Koštiál, Ivan. 1930. "Jezikovne drobtine." Ljubljanski zvon 50(3): 179–180, p. 180.

^ Reichenbach, Anton Benedict. 1848. Neueste Volks-Naturgeschichte des Thierreichs für Schule und Haus. Leipzig: Slawische Buchhandlung, p. 58.

^ Wessely, Josef. 1853. Die oesterreichischen Alpenlaender und ihre Forste. Vienna: Braumüller, p. 2.

^ Büsching, Anton Friedrich. 1762. A New System of Geography. Vol. 4. Trans. P. Murdoch. London: A. Millar, p. 214.

^ Smollett, Tobias George. 1769. The Present State of All Nations. London: Baldwin, p. 244.

^ Moodie, Arthur Edward. 1945. The Italo-Yugoslav Boundary: A Study in Political Geography. London: G. Philip & Son, p. 32.

^ Glasnik Etnografskog instituta. 52. Научно дело. 2004. p. 189.

^ ab Akademija nauka i umjetnosti Bosne i Hercegovine. Odjeljenje društvenih nauka (1970). Radovi odjeljenje društvenih nauka. 12. p. 158.

^ Etnografski institut (Srpska akademija nauka i umetnosti) (1960). Posebna izdanja. 10–14. Naučno delo. p. 16.

^ ab Prosvjeta: mjesečnik Srpskog kulturnog društva Prosvjeta. Društvo. 1969. pp. 8–10.

^ Subašić, B. (2014-01-29). "Belu Krajinu nema ko da čuva" (in Serbian). Novosti.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to White Carniola. |

Coordinates: 45°34′0″N 15°12′0″E / 45.56667°N 15.20000°E / 45.56667; 15.20000